-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Microbial Egress: A Hitchhiker's Guide to Freedom

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004201

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004201Summary

article has not abstract

The Restaurant at the End of the Infection—Macrophages as Host Cells

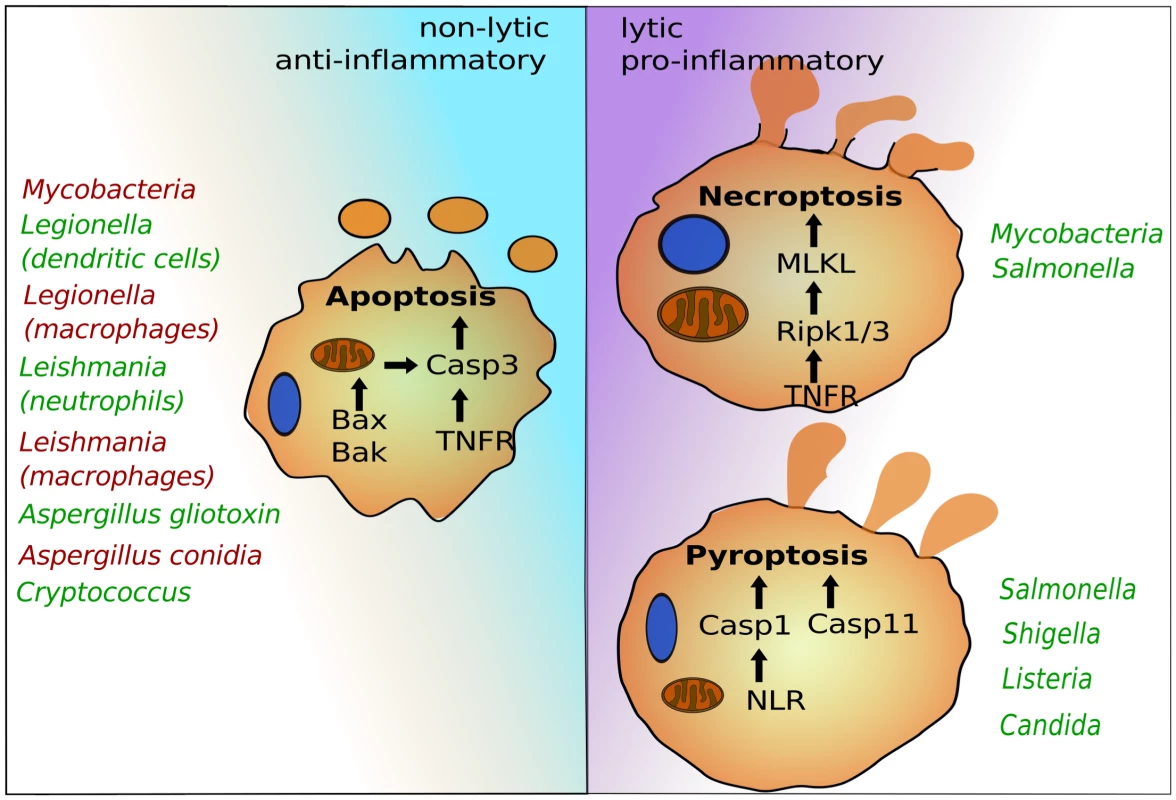

After colonization or invasion, intracellular pathogens seek host cells to establish infections and facilitate replication. This lifestyle provides essential nutrients and protection from immune systems. Several host cells—in particular professional phagocytes, such as monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils—have developed antimicrobial mechanisms to deplete the replicative niche of these intracellular microbes. Programmed cell death pathways are frontline defense mechanisms, whereby host cell suicide blocks intracellular microbial replication and exposes them for immune attack [1]. Recent advances have uncovered several programmed cell death pathways that are highly regulated to ensure proper immune responses. Besides canonical apoptosis, which initially preserves host cell integrity and is largely anti-inflammatory, macrophages can induce pyroptosis and necroptosis, which are both highly lytic and trigger proinflammatory signals (Figure 1). Pyroptosis depends on the cysteine-aspartic proteases, caspase-1 or caspase-11, which are activated by cytosolic pattern recognition receptors [1], [2]. Necroptosis is regulated by the TNFR (tumor necrosis factor receptor)-associated kinases, Ripk1 and 3, and is executed by MLKL (mixed lineage kinase domain-like) [3]. Successful intracellular pathogens must suppress programmed cell death signals during the replicative or latent phase but can potentially induce these signals to promote egress and dissemination. The timing and specificity of the cell death signal can dramatically influence pathogen or host survival, suggesting a complex interplay exists between inducing potent immunity and promoting pathogen egress. Most work in this area has focused on bacteria and parasites, but more recent studies have provided exciting evidence that fungal pathogens likewise modulate host cell death pathways.

Fig. 1. The programmed cell death pathways apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis play critical roles in egress of intracellular pathogens.

Intrinsic apoptosis is dependent on mitochondrial damage by Bax and Bak and activation of caspase-3. Caspase-3 can also be activated via cell surface receptors such as TNFR in the pathway of extrinsic apoptosis. Pyroptosis depends on caspase-1, which is activated by cytosolic NLRs, and caspase-11, for which the precise signaling pathway needs to be determined. Necroptosis requires Ripk1 and 3 and MLKL. Representative intracellular pathogens are listed that modulate these host suicide programs, either by blocking (red) or inducing (green) their activation. Life, Death, and Everything in between—Microbial Egress and Apoptosis

Generally, intracellular pathogens suppress apoptosis to promote replication. In addition, apoptosis can also block efficient escape, as is the case with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Figure 1) [4]. Avirulent Mycobacteria that fail to inhibit apoptosis become trapped, as the plasma membrane remains intact for several hours after host cell death. This leads to uptake and digestion of the apoptotic cell together with Mycobacteria by uninfected macrophages [4]. To prevent this, Mycobacteria induce necroptosis, which results in plasma membrane rupture, bacterial release, and survival [5]. The ability to interfere with cell death signaling can depend on the host cell involved. For example, dendritic cells, but not macrophages, rapidly undergo apoptosis and prevent intracellular replication of Legionella [6]. Another example is the protozoan parasite Leishmania, which also blocks apoptosis in macrophages [7]. However, the first phagocytes encountered during infection are neutrophils. After phagocytosis by neutrophils, Leishmania manages to move into a permissive niche of macrophages by inducing apoptosis of the infected neutrophil [8]. This is partly because the “find-me/eat-me” signal displayed by the apoptotic infected neutrophil triggers uptake of parasites and anti-inflammatory responses of macrophages that enable intracellular parasite survival [9]. Fungal pathogens also target apoptosis. Intracellular Aspergillus conidia block macrophage apoptosis by up-regulating prosurvival signaling, which leads to inhibition of caspase-3 activity [10]. This is thought to provide immune protection for conidia inside the phagocytes. For egress, intracellular conidia generate germ tubes and hyphae that appear to pierce through host membranes [11]. Hyphae secrete gliotoxin, which triggers intrinsic apoptosis of host immune cells by inducing mitochondrial pore formation via Bak and activation of caspase-3 [12], [13], but its role during egress remains ill defined. The facultative intracellular fungus Cryptococcus induces host cell apoptosis, which, in contrast to Mycobacteria, may in this case promote escape from macrophages. Intracellular Cryptococcus produces large amounts of the polysaccharide-enriched capsule, which is frequently shed into discrete host vesicles [14]. At least two capsule glycans, galactoxylomannan (GalXM) and glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), have been shown to activate apoptosis in macrophages either by inducing cell surface death receptors or via intrinsic Bax/Bak-dependent apoptosis [15]–[18]. While the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans also modulates apoptotic signaling [19], there is little evidence so far that egress from macrophages relies on host cell apoptosis [20]–[22].

Mostly Harmless—Pathogen Escape without Host Cell Lysis

Cytosolic microbes can also egress and spread between host cells via propulsive forces due to actin polymerization, which generates protrusions at the plasma membrane [23]. These protrusions are engulfed by neighboring cells, facilitating transfer of intracellular pathogens, such as Shigella, without host cell death. Vacuolar pathogens can also egress without host cell lysis. Inclusions of Chlamydia recruit and activate the myosin motor complex and are extruded from cells via actin polymerization [24]. Cryptococcus is known to hijack the ability of (phago)lysosomes to fuse directly with the plasma membrane, resulting in the release of lysosomal content including fungal cells [25], [26]. This form of nonlytic exocytosis or “vomocytosis” depends on the interplay between several host factors such as phagosomal pH, inflammatory signals, host cell microtubules, actin polymerization, and exocytosis signals [27], [28]. C. albicans has also been reported to escape from macrophages without concomitant macrophage lysis in a small fraction of cases (<1%) [29].

So Long and Thanks for All the Inflammatory Cell Death

In contrast to nonlytic escape, pathogens can also induce extensive host cell damage and death during egress. While some bacteria can escape from their vacuoles without causing concomitant host cell death [30], cytosolic bacteria, as well as microbial molecules that reach the cytosol, can be detected by NOD-like receptors (NLRs) that induce caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis (Figure 1) [1]. In addition, contamination of the cytosol by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) triggers pyroptosis via the activation of caspase-11 [31]. Others, like Shigella, induce caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis by triggering phagosome rupture caused by secretion of ion channels [32]. Vacuolar pathogens can also induce pyroptosis by secreting effector proteins that are recognized by NLRs into host cytosols [1], [33]. Besides pyroptosis, intracellular Salmonella may also activate necroptosis for escape from macrophages, at least under certain conditions [34]. Both pyroptosis and necroptosis trigger potent antimicrobial immune responses, but these types of lytic host cell death also result in rapid release of intracellular pathogens, enabling dissemination and replication in rich extracellular niches [1], [34]. Very recently, intracellular C. albicans has been shown to trigger caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis in macrophages, the first evidence of a fungal pathogen causing pyroptosis [20], [35]. This new discovery questions the long-standing view that C. albicans hyphal filaments kill macrophages by piercing host membranes [36]. Instead, phenotypes of several Candida mutants suggest that filaments contain additional features likely related to cell surface characteristics, which are necessary for induction of pyroptosis [20], [37], [38]. The cell wall carbohydrates, including β-glucans, are highly immunogenic because they are sensed by several macrophage lectin receptors, such as Dectin-1, that enable priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome [39], [40]. There is, however, little evidence that the β-glucans can trigger pyroptosis directly, suggesting that Candida may depend on additional factors. Other fungal pathogens, such as Aspergillus fumigatus, also induce caspase-1 activation [41]. Thus, pyroptosis could be a common mechanism for fungal egress. Of note, C. albicans hyphae can also egress from macrophage in a pyroptosis-independent manner, particularly when fungal loads are high [20], [35]. The precise nature of the pyroptosis-independent killing of macrophages by C. albicans remains to be determined, but it was proposed that it could represent necrotic death when macrophages are overloaded with fungal cells [35].

And Another Thing: Egress Pathways Determine Clinical Outcome

Induction of programmed cell pathways can dramatically determine the health of the host and the pathogen, suggesting that microbial egress via host cell suicide needs to be carefully balanced. For instance, caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis triggers potent antimicrobial responses targeted at escaped Salmonella [1], while caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis (in the absence of caspase-1 activation) actually promotes extracellular bacterial replication and dissemination to the detriment of the host [42]. Similarly, caspase-1-dependent immune response can trigger antifungal inflammation [40], but “hijacking” macrophage pyroptosis promotes rapid egress of C. albicans from macrophages [20], [35]. Not all proinflammatory responses result in clearance of intracellular pathogens. For example, Salmonella can utilize type 1 interferon signaling for egress from macrophages and for survival in mice [34], [42]. Furthermore, some microbes thrive under proinflammatory conditions, including Listeria and some Leishmania species, suggesting that the timing and manner of programmed cell death is critical for pathogen egress and disease [43]–[45]. In the case of tuberculosis, the level of inflammatory responses determines macrophage cell death signaling, disease progression, and pathogen clearance [5]. Finally, pathogen-provoked host cell death itself can contribute to disease outcome, as LPS-induced septic shock results from uncontrolled caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis [2]. Similarly, while caspase-1-dependent secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) has potent antifungal properties, symptoms of vaginal candidiasis are largely caused by sustained influx of neutrophils due to IL-1β secretion [46]. Given that immunopathology is also associated with fatal candidiasis [47], the fungal egress pathway in macrophages may directly contribute to disease progression.

Zdroje

1. MiaoEA, LeafIA, TreutingPM, MaoDP, DorsM, et al. (2010) Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol 11 : 1136–1142.

2. KayagakiN, WarmingS, LamkanfiM, Vande WalleL, LouieS, et al. (2011) Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479 : 117–121.

3. SunL, WangH, WangZ, HeS, ChenS, et al. (2012) Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148 : 213–227.

4. MartinCJ, BootyMG, RosebrockTR, Nunes-AlvesC, DesjardinsDM, et al. (2012) Efferocytosis is an innate antibacterial mechanism. Cell Host Microbe 12 : 289–300.

5. RocaFJ, RamakrishnanL (2013) TNF dually mediates resistance and susceptibility to mycobacteria via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell 153 : 521–534.

6. NogueiraCV, LindstenT, JamiesonAM, CaseCL, ShinS, et al. (2009) Rapid pathogen-induced apoptosis: a mechanism used by dendritic cells to limit intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000478.

7. SrivastavS, Basu BallW, GuptaP, GiriJ, UkilA, et al. (2014) Leishmania donovani prevents oxidative burst-mediated apoptosis of host macrophages through selective induction of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins. J Biol Chem 289 : 1092–1105.

8. van ZandbergenG, KlingerM, MuellerA, DannenbergS, GebertA, et al. (2004) Cutting edge: neutrophil granulocyte serves as a vector for Leishmania entry into macrophages. J Immunol 173 : 6521–6525.

9. PetersNC, EgenJG, SecundinoN, DebrabantA, KimblinN, et al. (2008) In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science 321 : 970–974.

10. VollingK, ThywissenA, BrakhageAA, SaluzHP (2011) Phagocytosis of melanized Aspergillus conidia by macrophages exerts cytoprotective effects by sustained PI3K/Akt signalling. Cell Microbiol 13 : 1130–1148.

11. WasylnkaJA, MooreMM (2002) Uptake of Aspergillus fumigatus Conidia by phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells in vitro: quantitation using strains expressing green fluorescent protein. Infect Immun 70 : 3156–3163.

12. StanzaniM, OrciuoloE, LewisR, KontoyiannisDP, MartinsSL, et al. (2005) Aspergillus fumigatus suppresses the human cellular immune response via gliotoxin-mediated apoptosis of monocytes. Blood 105 : 2258–2265.

13. GeisslerA, HaunF, FrankDO, WielandK, SimonMM, et al. (2013) Apoptosis induced by the fungal pathogen gliotoxin requires a triple phosphorylation of Bim by JNK. Cell Death Differ 20 : 1317–1329.

14. TuckerSC, CasadevallA (2002) Replication of Cryptococcus neoformans in macrophages is accompanied by phagosomal permeabilization and accumulation of vesicles containing polysaccharide in the cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 : 3165–3170.

15. VillenaSN, PinheiroRO, PinheiroCS, NunesMP, TakiyaCM, et al. (2008) Capsular polysaccharides galactoxylomannan and glucuronoxylomannan from Cryptococcus neoformans induce macrophage apoptosis mediated by Fas ligand. Cell Microbiol 10 : 1274–1285.

16. MonariC, PaganelliF, BistoniF, KozelTR, VecchiarelliA (2008) Capsular polysaccharide induction of apoptosis by intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. Cell Microbiol 10 : 2129–2137.

17. De JesusM, NicolaAM, FrasesS, LeeIR, MiesesS, et al. (2009) Galactoxylomannan-mediated immunological paralysis results from specific B cell depletion in the context of widespread immune system damage. J Immunol 183 : 3885–3894.

18. Ben-AbdallahM, Sturny-LeclereA, AveP, LouiseA, MoyrandF, et al. (2012) Fungal-induced cell cycle impairment, chromosome instability and apoptosis via differential activation of NF-kappaB. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002555.

19. Ibata-OmbettaS, IdziorekT, TrinelPA, PoulainD, JouaultT (2003) Candida albicans phospholipomannan promotes survival of phagocytosed yeasts through modulation of bad phosphorylation and macrophage apoptosis. J Biol Chem 278 : 13086–13093.

20. UwamahoroN, Verma-GaurJ, ShenHH, QuY, LewisR, et al. (2014) The Pathogen Candida albicans Hijacks Pyroptosis for Escape from Macrophages. MBio 5: e00003-14.

21. Reales-CalderonJA, SylvesterM, StrijbisK, JensenON, NombelaC, et al. (2013) Candida albicans induces pro-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic signals in macrophages as revealed by quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics. J Proteomics 91C: 106–135.

22. LionakisMS, SwamydasM, FischerBG, PlantingaTS, JohnsonMD, et al. (2013) CX3CR1-dependent renal macrophage survival promotes Candida control and host survival. J Clin Invest 123 : 5035–5051.

23. FukumatsuM, OgawaM, ArakawaS, SuzukiM, NakayamaK, et al. (2012) Shigella targets epithelial tricellular junctions and uses a noncanonical clathrin-dependent endocytic pathway to spread between cells. Cell Host Microbe 11 : 325–336.

24. LutterEI, BargerAC, NairV, HackstadtT (2013) Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT228 recruits elements of the myosin phosphatase pathway to regulate release mechanisms. Cell Rep 3 : 1921–1931.

25. AlvarezM, CasadevallA (2006) Phagosome extrusion and host-cell survival after Cryptococcus neoformans phagocytosis by macrophages. Curr Biol 16 : 2161–2165.

26. JohnstonSA, MayRC (2010) The human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans escapes macrophages by a phagosome emptying mechanism that is inhibited by Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerisation. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001041.

27. JohnstonSA, MayRC (2013) Cryptococcus interactions with macrophages: evasion and manipulation of the phagosome by a fungal pathogen. Cell Microbiol 15 : 403–411.

28. NicolaAM, RobertsonEJ, AlbuquerqueP, DerengowskiLdS, CasadevallA (2011) Nonlytic exocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans from macrophages occurs in vivo and is influenced by phagosomal pH. MBio 2: e00167-11.

29. BainJM, LewisLE, OkaiB, QuinnJ, GowNA, et al. (2012) Non-lytic expulsion/exocytosis of Candida albicans from macrophages. Fungal Genet Biol 49 : 677–678.

30. SauerJD, PereyreS, ArcherKA, BurkeTP, HansonB, et al. (2011) Listeria monocytogenes engineered to activate the Nlrc4 inflammasome are severely attenuated and are poor inducers of protective immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 12419–12424.

31. AachouiY, LeafIA, HagarJA, FontanaMF, CamposCG, et al. (2013) Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science 339 : 975–978.

32. SenerovicL, TsunodaSP, GoosmannC, BrinkmannV, ZychlinskyA, et al. (2012) Spontaneous formation of IpaB ion channels in host cell membranes reveals how Shigella induces pyroptosis in macrophages. Cell Death Dis 3: e384.

33. CassonCN, CopenhaverAM, ZwackEE, NguyenHT, StrowigT, et al. (2013) Caspase-11 Activation in Response to Bacterial Secretion Systems that Access the Host Cytosol. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003400.

34. RobinsonN, McCombS, MulliganR, DudaniR, KrishnanL, et al. (2012) Type I interferon induces necroptosis in macrophages during infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Nat Immunol 13 : 954–962.

35. WellingtonM, KoselnyK, SutterwalaFS, KrysanDJ (2014) Candida albicans triggers NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis in macrophages. Eukaryot Cell 13 : 329–340.

36. LoHJ, KohlerJR, DiDomenicoB, LoebenbergD, CacciapuotiA, et al. (1997) Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90 : 939–949.

37. WellingtonM, KoselnyK, KrysanDJ (2012) Candida albicans Morphogenesis Is Not Required for Macrophage Interleukin 1beta Production. MBio 4: e00433-12.

38. LowmanDW, GreeneRR, BeardenDW, KruppaMD, PottierM, et al. (2013) Novel structural features in Candida albicans hyphal glucan provide a basis for differential innate immune recognition of hyphae versus yeast. J Biol Chem 289 : 3432–3443.

39. KankkunenP, TeirilaL, RintahakaJ, AleniusH, WolffH, et al. (2010) (1,3)-beta-glucans activate both dectin-1 and NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages. J Immunol 184 : 6335–6342.

40. GrossO, PoeckH, BscheiderM, DostertC, HannesschlagerN, et al. (2009) Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 459 : 433–436.

41. Said-SadierN, PadillaE, LangsleyG, OjciusDM (2010) Aspergillus fumigatus stimulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through a pathway requiring ROS production and the Syk tyrosine kinase. PLoS ONE 5: e10008.

42. BrozP, RubyT, BelhocineK, BouleyDM, KayagakiN, et al. (2012) Caspase-11 increases susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1. Nature 490 : 288–291.

43. AuerbuchV, BrockstedtDG, Meyer-MorseN, O'RiordanM, PortnoyDA (2004) Mice lacking the type I interferon receptor are resistant to Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med 200 : 527–533.

44. O'ConnellRM, SahaSK, VaidyaSA, BruhnKW, MirandaGA, et al. (2004) Type I interferon production enhances susceptibility to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Exp Med 200 : 437–445.

45. XinL, Vargas-InchausteguiDA, RaimerSS, KellyBC, HuJ, et al. (2010) Type I IFN receptor regulates neutrophil functions and innate immunity to Leishmania parasites. J Immunol 184 : 7047–7056.

46. PetersBM, PalmerGE, FidelPLJr, NoverrMC (2013) Fungal morphogenetic pathways are required for the hallmark inflammatory response during Candida vaginitis. Infect Immun 82 : 532–543.

47. MajerO, BourgeoisC, ZwolanekF, LassnigC, KerjaschkiD, et al. (2012) Type I interferons promote fatal immunopathology by regulating inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils during Candida infections. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002811.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of KSHV Oncogenesis of Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated with HIV/AIDSČlánek The Semen Microbiome and Its Relationship with Local Immunology and Viral Load in HIV InfectionČlánek Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins Kill Bacteria by Inducing Oxidative, Thiol, and Metal Stress

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 7- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Choroby jater v ordinaci praktického lékaře – význam jaterních testů

- Diagnostický algoritmus při podezření na syndrom periodické horečky

- Perorální antivirotika jako vysoce efektivní nástroj prevence hospitalizací kvůli COVID-19 − otázky a odpovědi pro praxi

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Bacteriophages as Vehicles for Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Environment

- Helminth Infections, Type-2 Immune Response, and Metabolic Syndrome

- Defensins and Viral Infection: Dispelling Common Misconceptions

- Holobiont–Holobiont Interactions: Redefining Host–Parasite Interactions

- The Wide World of Ribosomally Encoded Bacterial Peptides

- Microbial Egress: A Hitchhiker's Guide to Freedom

- Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of KSHV Oncogenesis of Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated with HIV/AIDS

- HIV-1 Capture and Transmission by Dendritic Cells: The Role of Viral Glycolipids and the Cellular Receptor Siglec-1

- Tetherin Can Restrict Cell-Free and Cell-Cell Transmission of HIV from Primary Macrophages to T Cells

- The Frustrated Host Response to Is Bypassed by MyD88-Dependent Translation of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines

- Larger Mammalian Body Size Leads to Lower Retroviral Activity

- The Semen Microbiome and Its Relationship with Local Immunology and Viral Load in HIV Infection

- Lytic Gene Expression Is Frequent in HSV-1 Latent Infection and Correlates with the Engagement of a Cell-Intrinsic Transcriptional Response

- Phase Variation of Poly-N-Acetylglucosamine Expression in

- A Screen of Mutants Reveals Important Roles for Dot/Icm Effectors and Host Autophagy in Vacuole Biogenesis

- Structure of the Trehalose-6-phosphate Phosphatase from Reveals Key Design Principles for Anthelmintic Drugs

- The Impact of Juvenile Coxsackievirus Infection on Cardiac Progenitor Cells and Postnatal Heart Development

- Vertical Transmission Selects for Reduced Virulence in a Plant Virus and for Increased Resistance in the Host

- Characterization of the Largest Effector Gene Cluster of

- Novel Drosophila Viruses Encode Host-Specific Suppressors of RNAi

- Pto Kinase Binds Two Domains of AvrPtoB and Its Proximity to the Effector E3 Ligase Determines if It Evades Degradation and Activates Plant Immunity

- Genetic Analysis of Tropism Using a Naturally Attenuated Cutaneous Strain

- Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Suppress HIV-1 Replication but Contribute to HIV-1 Induced Immunopathogenesis in Humanized Mice

- A Novel Mouse Model of Gastroenteritis Reveals Key Pro-inflammatory and Tissue Protective Roles for Toll-like Receptor Signaling during Infection

- Pathogenicity of Is Expressed by Regulating Metabolic Thresholds of the Host Macrophage

- BCKDH: The Missing Link in Apicomplexan Mitochondrial Metabolism Is Required for Full Virulence of and

- Independent Bottlenecks Characterize Colonization of Systemic Compartments and Gut Lymphoid Tissue by

- Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins Kill Bacteria by Inducing Oxidative, Thiol, and Metal Stress

- G3BP1, G3BP2 and CAPRIN1 Are Required for Translation of Interferon Stimulated mRNAs and Are Targeted by a Dengue Virus Non-coding RNA

- Cytolethal Distending Toxins Require Components of the ER-Associated Degradation Pathway for Host Cell Entry

- The Machinery at Endoplasmic Reticulum-Plasma Membrane Contact Sites Contributes to Spatial Regulation of Multiple Effector Proteins

- Arabidopsis LIP5, a Positive Regulator of Multivesicular Body Biogenesis, Is a Critical Target of Pathogen-Responsive MAPK Cascade in Plant Basal Defense

- Plant Surface Cues Prime for Biotrophic Development

- Real-Time Imaging Reveals the Dynamics of Leukocyte Behaviour during Experimental Cerebral Malaria Pathogenesis

- The CD27L and CTP1L Endolysins Targeting Contain a Built-in Trigger and Release Factor

- cGMP and NHR Signaling Co-regulate Expression of Insulin-Like Peptides and Developmental Activation of Infective Larvae in

- Systemic Hematogenous Maintenance of Memory Inflation by MCMV Infection

- Strain-Specific Variation of the Decorin-Binding Adhesin DbpA Influences the Tissue Tropism of the Lyme Disease Spirochete

- Distinct Lipid A Moieties Contribute to Pathogen-Induced Site-Specific Vascular Inflammation

- Serovar Typhi Conceals the Invasion-Associated Type Three Secretion System from the Innate Immune System by Gene Regulation

- LANA Binds to Multiple Active Viral and Cellular Promoters and Associates with the H3K4Methyltransferase hSET1 Complex

- A Molecularly Cloned, Live-Attenuated Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine SA-14-2 Virus: A Conserved Single Amino Acid in the Hairpin of the Viral E Glycoprotein Determines Neurovirulence in Mice

- Illuminating Fungal Infections with Bioluminescence

- Comparative Genomics of Plant Fungal Pathogens: The - Paradigm

- Motility and Chemotaxis Mediate the Preferential Colonization of Gastric Injury Sites by

- Widespread Sequence Variations in VAMP1 across Vertebrates Suggest a Potential Selective Pressure from Botulinum Neurotoxins

- An Immunity-Triggering Effector from the Barley Smut Fungus Resides in an Ustilaginaceae-Specific Cluster Bearing Signs of Transposable Element-Assisted Evolution

- Establishment of Murine Gammaherpesvirus Latency in B Cells Is Not a Stochastic Event

- Oncogenic Herpesvirus KSHV Hijacks BMP-Smad1-Id Signaling to Promote Tumorigenesis

- Human APOBEC3 Induced Mutation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Contributes to Adaptation and Evolution in Natural Infection

- Innate Immune Responses and Rapid Control of Inflammation in African Green Monkeys Treated or Not with Interferon-Alpha during Primary SIVagm Infection

- Chitin-Degrading Protein CBP49 Is a Key Virulence Factor in American Foulbrood of Honey Bees

- Influenza A Virus Host Shutoff Disables Antiviral Stress-Induced Translation Arrest

- Nsp9 and Nsp10 Contribute to the Fatal Virulence of Highly Pathogenic Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Emerging in China

- Pulmonary Infection with Hypervirulent Mycobacteria Reveals a Crucial Role for the P2X7 Receptor in Aggressive Forms of Tuberculosis

- Syk Signaling in Dendritic Cells Orchestrates Innate Resistance to Systemic Fungal Infection

- A Repetitive DNA Element Regulates Expression of the Sialic Acid Binding Adhesin by a Rheostat-like Mechanism

- T-bet and Eomes Are Differentially Linked to the Exhausted Phenotype of CD8+ T Cells in HIV Infection

- Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Implications for Honey Bee Health

- Influence of ND10 Components on Epigenetic Determinants of Early KSHV Latency Establishment

- Antibody to gp41 MPER Alters Functional Properties of HIV-1 Env without Complete Neutralization

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of KSHV Oncogenesis of Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated with HIV/AIDS

- Holobiont–Holobiont Interactions: Redefining Host–Parasite Interactions

- BCKDH: The Missing Link in Apicomplexan Mitochondrial Metabolism Is Required for Full Virulence of and

- Helminth Infections, Type-2 Immune Response, and Metabolic Syndrome

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání