-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Bacteriophages as Vehicles for Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Environment

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 10(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004219

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004219Summary

article has not abstract

Occurrence and Impact of Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic therapy represents one of the most important medical advances of the 20th century and is a valuable resource in combating infectious diseases. Its therapeutic use, however, has been associated with the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. There are many naturally occurring ways in which susceptible bacteria become resistant to antibiotics, including by chromosomal mutations and/or horizontal gene transfer. The latter is largely, although not exclusively, responsible for the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria through various processes such as conjugation, transformation, and transduction [1].

Transduction is a mechanism of genetic exchange, which is mediated by independently replicating bacterial viruses called bacteriophages, or phages [2]. Although the acquisition of antimicrobial resistance by transduction has been demonstrated in clinically relevant bacterial species, this mechanism in environmental settings has not been fully explored. However, cutting-edge genomic technologies such as high-throughput sequencing have recently led to significant advances in our understanding of the contribution of phages to the spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). This article will, therefore, describe the current knowledge on the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment, with special emphasis on the role of phages in the mobilization of ARGs. Understanding sources and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance is critical for developing effective strategies for reducing their impact on public and environmental health.

Genetic Exchange Mediated by Phages

Phages are viruses consisting of a DNA or RNA genome surrounded by a protein coat (capsid). They are the most abundant biological entities in the biosphere, with an estimated total population of 1030–1032 [3], [4]. Phages infect bacteria and either incorporate their viral genome into the host genome, replicating as part of the host (lysogenic cycle), or multiply inside the host cell before releasing new phage particles (lytic cycle).

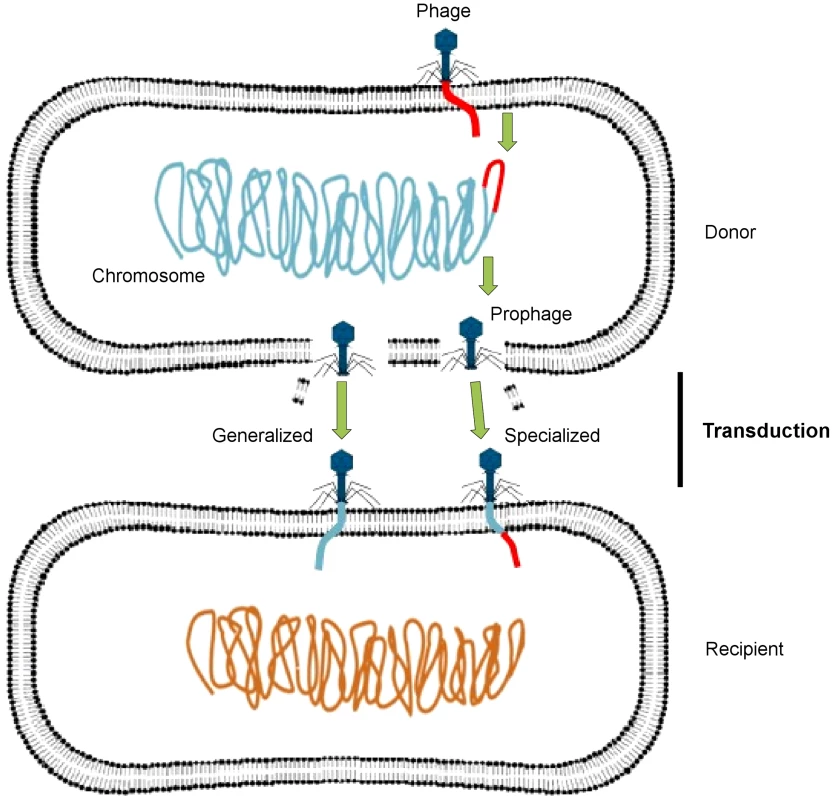

Phages may act as vectors for genetic exchange via generalized or specialized transduction, whereby a genetic trait is carried by phage particles from a donor bacterial cell to a recipient cell (Figure 1). Generalized transduction implicates the transfer of any portion of the donor genome to the recipient cell by either a lytic or lysogenic (temperate) phage, whereas specialized transduction involves only temperate phages, in which a few specific donor genes can be transferred to the recipient cell. A specialized transducing phage produces particles that carry both chromosomal DNA and phage DNA and contains only specific regions of the bacterial chromosome located adjacent to the prophage attachment site. Some temperate phages may also induce a change in the phenotype of the infected host, through a process known as lysogenic conversion [4].

Fig. 1. Transfer of DNA between bacteria via phages.

A temperate phage inserts its genome (red) into the bacterial chromosome (blue-green) as a prophage, which replicates along with the bacterial chromosome, packaging host DNA alone (generalized transduction) or with its own DNA (specialized transduction). It then lyses the bacterial cell, releasing progeny phage particles into the surrounding environment. After lysis, these phages infect new bacterial cells, in which the acquired DNA recombines with the recipient cell chromosome (orange). This figure has been adapted from Frost et al. [2]. Through these mechanisms, phages play an important role in the evolution and ecology of bacterial species, as they have the potential to transfer genetic material between bacteria. A metagenomic study has recently revealed that the viral metagenome (or virome) of antibiotic-treated mice was highly enriched for ARGs compared with that of nontreated control mice [5]. The authors also demonstrated that ex vivo infection of an aerobically cultured naive microbiota with phages from antibiotic-treated mice resulted in an increased bacterial resistance compared to infection with phages from the nontreated control. These findings clearly show that phages have significant implications for the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance.

Phages as Vehicles for Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Although antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon, the widespread use of antibiotics has contributed to the increase of antibiotic resistance in bacteria, including those causing infections in both humans and animals. Several studies suggest that antibiotic resistance found in clinical settings is intimately associated with the same mechanisms as those found in the environment [6]. In fact, the environment is continually exposed to a wide variety of antimicrobials and their metabolites through wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) discharges, agricultural runoff, and animal feeding operations, which may contribute to the emergence and spread of ARGs. Moreover, the large-scale mixing of environmental bacteria with exogenous bacteria from anthropogenic sources provides the ideal selective and ecological conditions for the emergence of resistant bacteria [7]. ARGs may be acquired and transferred among bacteria via mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as conjugative plasmids, insertion sequences, integrons, transposons, and phages. Although the importance of these MGEs is widely recognized [1], the contribution of phages to the spread of ARGs has not been fully explored in environmental settings.

Recent findings, however, suggest that phages may play a more significant role in the emergence and spread of ARGs than previously expected. An extensive study using both sequence - and function-based metagenomic approaches revealed the presence of ARG-like genes in the virome of activated sludge, which could confer resistance to several antibiotics, including tetracycline, ampicillin, and bleomycin. None of the sequenced clones, however, conferred their predicted antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli, likely due to incomplete cloning of the gene or lack of expression in E. coli [8]. Interestingly, a study using real-time PCR (qPCR) assays revealed the presence of two genes (blaTEM and blaCTX-M) encoding β-lactamases and one gene (mecA) encoding a penicillin-binding protein in phage DNA from urban sewage and river water samples. In contrast to the previous study, the authors demonstrated that those ARGs (blaTEM and blaCTX-M) from phage DNA were transferred to susceptible E. coli strains, which became resistant to ampicillin [9]. Another study of phage DNA from different hospital and urban treated effluents using qPCR assays showed the presence of high levels of genes (blaTEM, blaCTX-M and blaSHV) conferring resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, as well as genes (qnrA, qnrB and qnrS) conferring reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones [10]. Likewise, a recent study demonstrated the presence of the qnrA and qnrS genes in phage DNA from fecally polluted waters and the influence of phage-inducing factors on the abundance of those ARGs. They observed that urban wastewater samples treated with chelating agents, such as EDTA and sodium citrate, showed a significant increase in the copy number of those ARGs in phage DNA compared to the nontreated samples [11]. Taken together, these studies not only suggest that anthropogenic inputs may facilitate the emergence of ARGs but also demonstrate the contribution of phages to the spread of ARGs into the environment.

Metagenomic Exploration of Antibiotic Resistance in Environmental Settings

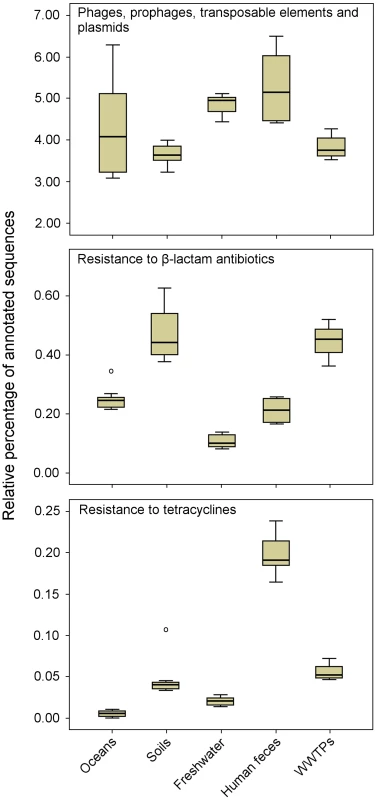

Shotgun sequencing of metagenomic DNA offers significant advantages over culture-dependent methods, because it allows a better understanding of the structure and function of naturally occurring microbial communities [12]. This has resulted in the sequencing of thousands of metagenomes, which are now available via public platforms such as MG-RAST [13] and IMG/M [14]. These sequenced metagenomes can be used to explore the resistome in diverse environments. As an example, a comparison of 27 metagenomes (data available publically) corresponding to several projects and environments using the MG-RAST platform [13] revealed a relatively high proportion of sequences related to MGEs, including phages, among microbial communities from different natural environments (Figure 2). These results suggest that natural environments are a substantial source of MGEs, which may contribute to the horizontal transfer and spread of ARGs. The comparative analysis also revealed that the sequences related to genes conferring resistance to β-lactam antibiotics were detected more frequently among microbial communities from soil and WWTP environments than those from oceans, freshwaters, and human feces. Likewise, the sequences related to genes encoding tetracycline resistance were more abundant among microbial communities from human feces.

Fig. 2. Metagenomic exploration of the resistome from human and environmental sources.

Relative distribution of reads assigned to three functional subsystems among 27 metagenomes (based on MG-RAST annotation, E-value = 10−5). Data are normalized by the total annotated sequences and are expressed as a percentage. The horizontal line in each box plot represents the mean of the relative distribution in each of the five environments (oceans, soils, freshwater, human feces, and WWTPs). The 27 metagenomes used for the analysis are available at http://metagenomics.anl.gov [13]. Accession numbers for oceans: 4441573.3, 4441574.3, 4441576.3, 4441577.3, 4441591.3, and 4443729.3; soils: 4441091.3, 4445990.3, 4445993.3, 4445994.3, 4445996.3, and 4446153.3; freshwater (rivers): 4511251.3, 4511252.3, 4511254.3, 4511255.3, 4511256.3, and 4511257.3; human feces: 4440595.4, 4440460.5, 4440611.3, 4440614.3, 4440825.3, and 4461119.3; and WWTPs: 4455295.3, 4463936.3, and 4467420.3. Metagenomic approaches offer valuable tools to explore the microbial community composition, ARGs, and MGEs in different environments. These environments may be further analyzed via clone libraries and functional screening in order to determine the role of MGEs (i.e., phages) as vehicles for ARGs. Therefore, high-throughput technologies, such as functional metagenomics, will provide unprecedented opportunities to elucidate the mechanisms and pathways by which antibiotic resistance evolves and spreads.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

It is now clearer than ever that the environment is a vast reservoir of resistant organisms and their associated genes. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that ARGs found in human microbial communities are likely to have been acquired from environmental sources [15], [16]. In fact, the use of metagenomic data generated via high-throughput sequencing has revealed that most ARGs found in nonpathogenic soil bacteria have perfect nucleotide identity to ARGs from several human pathogens, suggesting that recent horizontal gene transfer via MGEs has occurred between those organisms [17]. Metagenomic studies also demonstrate that phages, which may act as vehicles for ARGs, are widely distributed in nature. As a consequence, further studies should include the role of phages in developing effective strategies and mitigating the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance, because this phenomenon is a significant and growing public health concern. A better understanding of the mechanisms and factors involved in phage induction will be crucial to reach these goals.

Zdroje

1. MartiE, VariatzaE, BalcazarJL (2014) The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol 22 : 36–41.

2. FrostLS, LeplaeR, SummersAO, ToussaintA (2005) Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 3 : 722–732.

3. Chibani-ChennoufiS, BruttinA, DillmannM-L, BrüssowH (2004) Phage-host interaction: an ecological perspective. J Bacteriol 186 : 3677–3686.

4. BrabbanAD, HiteE, CallawayTR (2005) Evolution of foodborne pathogens via temperate bacteriophage-mediated gene transfer. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2 : 287–303.

5. ModiSR, LeeHH, SpinaCS, CollinsJJ (2013) Antibiotic treatment expands the resistance reservoir and ecological network of the phage metagenome. Nature 499 : 219–223.

6. D'CostaVM, GriffithsE, WrightGD (2007) Expanding the soil antibiotic resistome: exploring environmental diversity. Curr Opin Microbiol 10 : 481–489.

7. WellingtonEMH, BoxallABA, CrossP, FeilEJ, GazeWH, et al. (2013) The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis 13 : 155–165.

8. ParsleyLC, ConsuegraEJ, KakirdeKS, LandAM, HarperWFJr, et al. (2010) Identification of diverse antimicrobial resistance determinants carried on bacterial, plasmid, or viral metagenomes from an activated sludge microbial assemblage. Appl Environ Microbiol 76 : 3753–3757.

9. Colomer-LluchM, JofreJ, MuniesaM (2011) Antibiotic resistance genes in the bacteriophage DNA fraction of environmental samples. PLoS ONE 6: e17549.

10. MartiE, VariatzaE, BalcázarJL (2014) Bacteriophages as a reservoir of extended-spectrum β-lactamase and fluoroquinolone resistance genes in the environment. Clin Microbiol Infect E-pub ahead of print. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12446

11. Colomer-LluchM, JofreJ, MuniesaM (2014) Quinolone resistance genes (qnrA and qnrS) in bacteriophage particles from wastewater samples and the effect of inducing agents on packaged antibiotic resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 69 : 1265–1274.

12. MonierJ-M, DemanècheS, DelmontTO, MathieuA, VogelTM, et al. (2011) Metagenomic exploration of antibiotic resistance in soil. Curr Opin Microbiol 14 : 229–235.

13. MeyerF, PaarmannD, D'SouzaM, OlsonR, GlassEM, et al. (2008) The metagenomics RAST server – a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 9 : 386.

14. MarkowitzVM, ChenIMA, PalaniappanK, ChuK, SzetoE, et al. (2012) IMG: the integrated microbial genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D115–D122.

15. WrightGD (2010) Antibiotic resistance in the environment: a link to the clinic? Curr Opin Microbiol 13 : 589–594.

16. PrudenA (2014) Balancing water sustainability and public health goals in the fate of growing concerns about antibiotic resistance. Environ Sci Technol 48 : 5–14.

17. ForsbergKJ, ReyesA, WangB, SelleckEM, SommerMO, et al. (2012) The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. Science 337 : 1107–1111.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of KSHV Oncogenesis of Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated with HIV/AIDSČlánek The Semen Microbiome and Its Relationship with Local Immunology and Viral Load in HIV InfectionČlánek Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins Kill Bacteria by Inducing Oxidative, Thiol, and Metal Stress

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 7- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Autoinflamatorní onemocnění: prognózu zlepšuje včasná diagnostika a protizánětlivá terapie

- Získaná hemofilie – vzácná a závažná diagnóza, kde je třeba neztrácet čas

- Familiární středomořská horečka

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Bacteriophages as Vehicles for Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Environment

- Helminth Infections, Type-2 Immune Response, and Metabolic Syndrome

- Defensins and Viral Infection: Dispelling Common Misconceptions

- Holobiont–Holobiont Interactions: Redefining Host–Parasite Interactions

- The Wide World of Ribosomally Encoded Bacterial Peptides

- Microbial Egress: A Hitchhiker's Guide to Freedom

- Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of KSHV Oncogenesis of Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated with HIV/AIDS

- HIV-1 Capture and Transmission by Dendritic Cells: The Role of Viral Glycolipids and the Cellular Receptor Siglec-1

- Tetherin Can Restrict Cell-Free and Cell-Cell Transmission of HIV from Primary Macrophages to T Cells

- The Frustrated Host Response to Is Bypassed by MyD88-Dependent Translation of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines

- Larger Mammalian Body Size Leads to Lower Retroviral Activity

- The Semen Microbiome and Its Relationship with Local Immunology and Viral Load in HIV Infection

- Lytic Gene Expression Is Frequent in HSV-1 Latent Infection and Correlates with the Engagement of a Cell-Intrinsic Transcriptional Response

- Phase Variation of Poly-N-Acetylglucosamine Expression in

- A Screen of Mutants Reveals Important Roles for Dot/Icm Effectors and Host Autophagy in Vacuole Biogenesis

- Structure of the Trehalose-6-phosphate Phosphatase from Reveals Key Design Principles for Anthelmintic Drugs

- The Impact of Juvenile Coxsackievirus Infection on Cardiac Progenitor Cells and Postnatal Heart Development

- Vertical Transmission Selects for Reduced Virulence in a Plant Virus and for Increased Resistance in the Host

- Characterization of the Largest Effector Gene Cluster of

- Novel Drosophila Viruses Encode Host-Specific Suppressors of RNAi

- Pto Kinase Binds Two Domains of AvrPtoB and Its Proximity to the Effector E3 Ligase Determines if It Evades Degradation and Activates Plant Immunity

- Genetic Analysis of Tropism Using a Naturally Attenuated Cutaneous Strain

- Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Suppress HIV-1 Replication but Contribute to HIV-1 Induced Immunopathogenesis in Humanized Mice

- A Novel Mouse Model of Gastroenteritis Reveals Key Pro-inflammatory and Tissue Protective Roles for Toll-like Receptor Signaling during Infection

- Pathogenicity of Is Expressed by Regulating Metabolic Thresholds of the Host Macrophage

- BCKDH: The Missing Link in Apicomplexan Mitochondrial Metabolism Is Required for Full Virulence of and

- Independent Bottlenecks Characterize Colonization of Systemic Compartments and Gut Lymphoid Tissue by

- Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins Kill Bacteria by Inducing Oxidative, Thiol, and Metal Stress

- G3BP1, G3BP2 and CAPRIN1 Are Required for Translation of Interferon Stimulated mRNAs and Are Targeted by a Dengue Virus Non-coding RNA

- Cytolethal Distending Toxins Require Components of the ER-Associated Degradation Pathway for Host Cell Entry

- The Machinery at Endoplasmic Reticulum-Plasma Membrane Contact Sites Contributes to Spatial Regulation of Multiple Effector Proteins

- Arabidopsis LIP5, a Positive Regulator of Multivesicular Body Biogenesis, Is a Critical Target of Pathogen-Responsive MAPK Cascade in Plant Basal Defense

- Plant Surface Cues Prime for Biotrophic Development

- Real-Time Imaging Reveals the Dynamics of Leukocyte Behaviour during Experimental Cerebral Malaria Pathogenesis

- The CD27L and CTP1L Endolysins Targeting Contain a Built-in Trigger and Release Factor

- cGMP and NHR Signaling Co-regulate Expression of Insulin-Like Peptides and Developmental Activation of Infective Larvae in

- Systemic Hematogenous Maintenance of Memory Inflation by MCMV Infection

- Strain-Specific Variation of the Decorin-Binding Adhesin DbpA Influences the Tissue Tropism of the Lyme Disease Spirochete

- Distinct Lipid A Moieties Contribute to Pathogen-Induced Site-Specific Vascular Inflammation

- Serovar Typhi Conceals the Invasion-Associated Type Three Secretion System from the Innate Immune System by Gene Regulation

- LANA Binds to Multiple Active Viral and Cellular Promoters and Associates with the H3K4Methyltransferase hSET1 Complex

- A Molecularly Cloned, Live-Attenuated Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine SA-14-2 Virus: A Conserved Single Amino Acid in the Hairpin of the Viral E Glycoprotein Determines Neurovirulence in Mice

- Illuminating Fungal Infections with Bioluminescence

- Comparative Genomics of Plant Fungal Pathogens: The - Paradigm

- Motility and Chemotaxis Mediate the Preferential Colonization of Gastric Injury Sites by

- Widespread Sequence Variations in VAMP1 across Vertebrates Suggest a Potential Selective Pressure from Botulinum Neurotoxins

- An Immunity-Triggering Effector from the Barley Smut Fungus Resides in an Ustilaginaceae-Specific Cluster Bearing Signs of Transposable Element-Assisted Evolution

- Establishment of Murine Gammaherpesvirus Latency in B Cells Is Not a Stochastic Event

- Oncogenic Herpesvirus KSHV Hijacks BMP-Smad1-Id Signaling to Promote Tumorigenesis

- Human APOBEC3 Induced Mutation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Contributes to Adaptation and Evolution in Natural Infection

- Innate Immune Responses and Rapid Control of Inflammation in African Green Monkeys Treated or Not with Interferon-Alpha during Primary SIVagm Infection

- Chitin-Degrading Protein CBP49 Is a Key Virulence Factor in American Foulbrood of Honey Bees

- Influenza A Virus Host Shutoff Disables Antiviral Stress-Induced Translation Arrest

- Nsp9 and Nsp10 Contribute to the Fatal Virulence of Highly Pathogenic Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Emerging in China

- Pulmonary Infection with Hypervirulent Mycobacteria Reveals a Crucial Role for the P2X7 Receptor in Aggressive Forms of Tuberculosis

- Syk Signaling in Dendritic Cells Orchestrates Innate Resistance to Systemic Fungal Infection

- A Repetitive DNA Element Regulates Expression of the Sialic Acid Binding Adhesin by a Rheostat-like Mechanism

- T-bet and Eomes Are Differentially Linked to the Exhausted Phenotype of CD8+ T Cells in HIV Infection

- Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Implications for Honey Bee Health

- Influence of ND10 Components on Epigenetic Determinants of Early KSHV Latency Establishment

- Antibody to gp41 MPER Alters Functional Properties of HIV-1 Env without Complete Neutralization

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of KSHV Oncogenesis of Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated with HIV/AIDS

- Holobiont–Holobiont Interactions: Redefining Host–Parasite Interactions

- BCKDH: The Missing Link in Apicomplexan Mitochondrial Metabolism Is Required for Full Virulence of and

- Helminth Infections, Type-2 Immune Response, and Metabolic Syndrome

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání