-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

Fruit fly geneticists rely on a handful of dominant mutations that modify adult morphology in a way that is easy to spot, like changing the shape of the fly’s wings, eyes or bristles. One of the first such mutants identified in the early days of fly genetics and to this day likely the most widely used mutation, is Curly, which causes an upward curvature in the adult wings. Despite its importance as a marker, the genetic cause of Curly has remained unknown. Here, we reveal that Curly mutations occur in the gene duox, which encodes a ROS-generating enzyme. ROS once thought to be merely harmful by-products of metabolism, can also have beneficial purposes. Here we provide evidence that Duox generates ROS to help form and stabilize the wings of fruit flies. Furthermore, we identify a second enzyme, Cysu, which uses the ROS generated by Duox to crosslink proteins in the wing, thereby stabilizing and shaping its structure. Duox occurs in numerous organisms, including humans and fulfills a number of other functions, in particular in immunity and pathogen defense. With this new knowledge, Curly mutations will provide an excellent tool to study and understand the roles Duox plays in a variety of biological contexts.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 11(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005625

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005625Summary

Fruit fly geneticists rely on a handful of dominant mutations that modify adult morphology in a way that is easy to spot, like changing the shape of the fly’s wings, eyes or bristles. One of the first such mutants identified in the early days of fly genetics and to this day likely the most widely used mutation, is Curly, which causes an upward curvature in the adult wings. Despite its importance as a marker, the genetic cause of Curly has remained unknown. Here, we reveal that Curly mutations occur in the gene duox, which encodes a ROS-generating enzyme. ROS once thought to be merely harmful by-products of metabolism, can also have beneficial purposes. Here we provide evidence that Duox generates ROS to help form and stabilize the wings of fruit flies. Furthermore, we identify a second enzyme, Cysu, which uses the ROS generated by Duox to crosslink proteins in the wing, thereby stabilizing and shaping its structure. Duox occurs in numerous organisms, including humans and fulfills a number of other functions, in particular in immunity and pathogen defense. With this new knowledge, Curly mutations will provide an excellent tool to study and understand the roles Duox plays in a variety of biological contexts.

Introduction

Over 90 years ago, Lenore Ward first described a dominant mutation, Curly, that causes the wings of Drosophila melanogaster to bend upwards [1]. Since then, Curly has become a ubiquitous second chromosomal marker used by Drosophila geneticists on a daily basis to follow and track mutations. Despite its widespread use, how Curly mutations dominantly alter wing curvature has remained obscure. Waddington first proposed that Curly causes an unequal contraction of the dorsal and ventral wing surfaces during the drying period shortly after flies emerge from their pupal cases [2, 3]. Others have subsequently demonstrated that comparable alterations in wing curvature can be caused by differential growth of the dorsal and ventral epithelia [4]. Irrespective of the mechanism, that similar wing phenotypes have been described for D. pseudoobscura and D. montium mutants [5] suggests the underlying cause of curly wing formation is evolutionarily conserved among Drosophilids [2]. The major factor limiting our understanding of Curly’s function in wing morphogenesis, however, is the fact that its molecular identity has remained unknown.

In this manuscript we uncover the long unknown molecular nature of Curly. We show that mutations in the gene duox cause the Curly wing phenotype. Duox is a member of a highly conserved group of transmembrane proteins collectively referred to as NADPH oxidases. These enzymes function to transfer electrons across biological membranes to generate ROS by transferring electrons from NADPH to oxygen through flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and heme cofactors [6]. Several biological functions have been described for Duox. Perhaps the best studied of these in Drosophila is its role in host defense where it is thought to generate ROS to kill pathogens [7]. However, Duox also plays an important role in providing ROS, specifically hydrogen peroxide, for heme peroxidases to catalyze the formation of covalent bonds between biomolecules. In mammals, Duox generates hydrogen peroxide for thyroid peroxidase to catalyze the iodination and crosslinking of tyrosine residues in the formation of thyroid hormones [8, 9]. Duox is also expressed in tissues other than the thyroid, such as the gastrointestinal tract, where its function is less clear [6]. In insects, worms and sea urchins, Duox participates in the formation of extracellular structures through the crosslinking of tyrosine residues [10–12]. Indeed, instead of its function in generating bactericidal ROS, the tyrosine crosslinking activity of Duox may be the primary ancestral function, as it appears to be conserved across phyla.

Here we show that specific mutations in the NADPH binding-domain encoding region of duox cause a Curly wing phenotype. Using Curly, we demonstrate that duox is required during the last day of pupal development to stabilize the wing. Furthermore, through suppression experiments, we identify a novel heme peroxidase, Curly Su (Cysu), that works with duox to adhere the dorsal surface of the wing to the ventral one. Uncovering the molecular identity of Curly not only provides an entry point for the functional understanding of this prominent wing mutant phenotype, but also will allow for the discovery of novel duox interacting genes and regulators through unbiased genetic screens. Only through these approaches can we hope to understand the precise molecular function of Duox in the myriad biological processes in which it is involved.

Results

Curly mutations occur within duox

In the course of genetically following a loss-of-function mutation in the gene duox, duoxKG07745, using the standard Drosophila genetic tool Curly of Oster (CyO) balancer, we noticed that we were unable to recover progeny containing both duoxKG07745 and CyO. Since a) duox and Curly mutations fail to complement one another and b) Curly roughly maps to 23A4-23B2 [13], the chromosomal region containing duox, we wondered whether Curly might be an allele of duox.

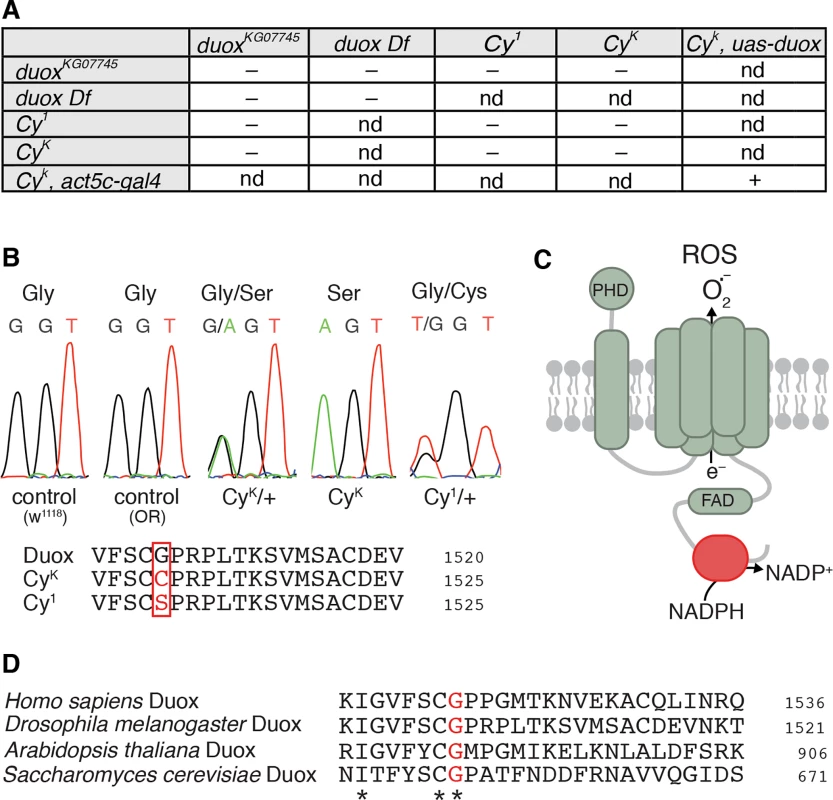

Balancer chromosomes contain numerous inversions and chromosomal aberrations. To exclude the possibility that our inability to recover progeny was due to some other lesion in the 23A4-23B2 region of CyO, we crossed duox KG07745 to various Curly mutations not associated with CyO [1, 13, 14]. Consistent with our earlier results, all the Curly alleles tested failed to complement duoxKG07745, suggesting that Curly mutations indeed reside within the duox locus (Fig 1A). To provide conclusive evidence, however, that duox and Curly are one and the same, we expressed duox ubiquitously in a Curly mutant background. Ubiquitous expression of duox restored viability, allowing recovery of homozygous Curly mutants (Fig 1A). These results strongly suggest that the Curly phenotype is due to mutations in the duox gene.

Fig. 1. Curly is an allele of duox.

(A) duox mutations fail to complement Curly mutations. Curly mutations are lethal as homozygotes and as transheterozygotes with a duox mutation or a deficiency uncovering the duox locus. Ubiquitous expression of duox restores viability to homozygous Curly mutants.– = not viable, + = viable, and nd = not determined. (B) Curly mutations cause a single amino acid change of a conserved glycine to either serine or cysteine for CyK or Cy1, respectively. (C) Cartoon of Duox. In red is the NADPH binding domain. PHD stands for peroxidase homology domain. (D) The conserved glycine residue mutated in Curly is an essential amino acid in the NADPH binding domain of Duox. Curly mutations occur in the NADPH-binding pocket encoding region of duox

To precisely determine how Curly mutations alter duox’s nucleotide sequence, we sequenced duox in two Curly mutants: CyK, which was previously generated using ethyl methanesulfonate [14]; and Cy1, the original spontaneous mutation identified by Ward [1]. Remarkably, we found that the same nucleotide was mutated in both CyK and Cy1 (Fig 1B). This single nucleotide mutation resulted in the conversion of a conserved glycine (number 1505) in the NADPH binding domain of Duox to a serine in CyK and to a cysteine in Cy1 (Fig 1C, red). Among the residues within the NADPH binding pocket of Duox, glycine 1505 is extraordinarily well conserved. It is present in all known NADPH oxidases from yeast to humans (Fig 1D), suggesting that it is functionally important. Therefore a conversion of a conserved glycine to a polar amino acid specifically in the NADPH binding pocket of Duox causes Curly. Taken together, our results demonstrate, after more than 90 years since its discovery, that the Curly phenotype is due to mutations within the duox gene.

Curly is likely a neomorphic allele of duox

Mutations in the NADPH binding encoding region of duox cause a Curly phenotype, but how exactly do they influence Duox’s function? From complementation experiments, it is clear that Curly mutations reduce Duox’s normal function as they are not viable in combination with either a loss-of-function duox mutation or a deficiency uncovering the duox locus (Fig 1A). However, Curly mutants also act dominantly, causing the wings of Curly flies to bend upwards (hence the name) in contrast to the straight wings of wild-type or duox heterozygous flies. One possible explanation is that Curly mutations act in opposition to Duox’s normal activity as dominant negatives or antimorphs. This, however, is unlikely because ubiquitous overexpression of wild-type Duox in a Curly mutant background failed to restore normal wing shape (S1 Fig). Another possibility is that Curly mutations increase the normal function of Duox either by increasing expression or constitutively activating Duox. However, this too seems implausible because removing wild-type Duox in Curly mutants worsened (causing lethality) rather than ameliorated the viability phenotype (Fig 1A). Instead, the most likely explanation is that Curly mutations are neomorphic, causing a dominant gain-of-function in Duox that is different from its normal function.

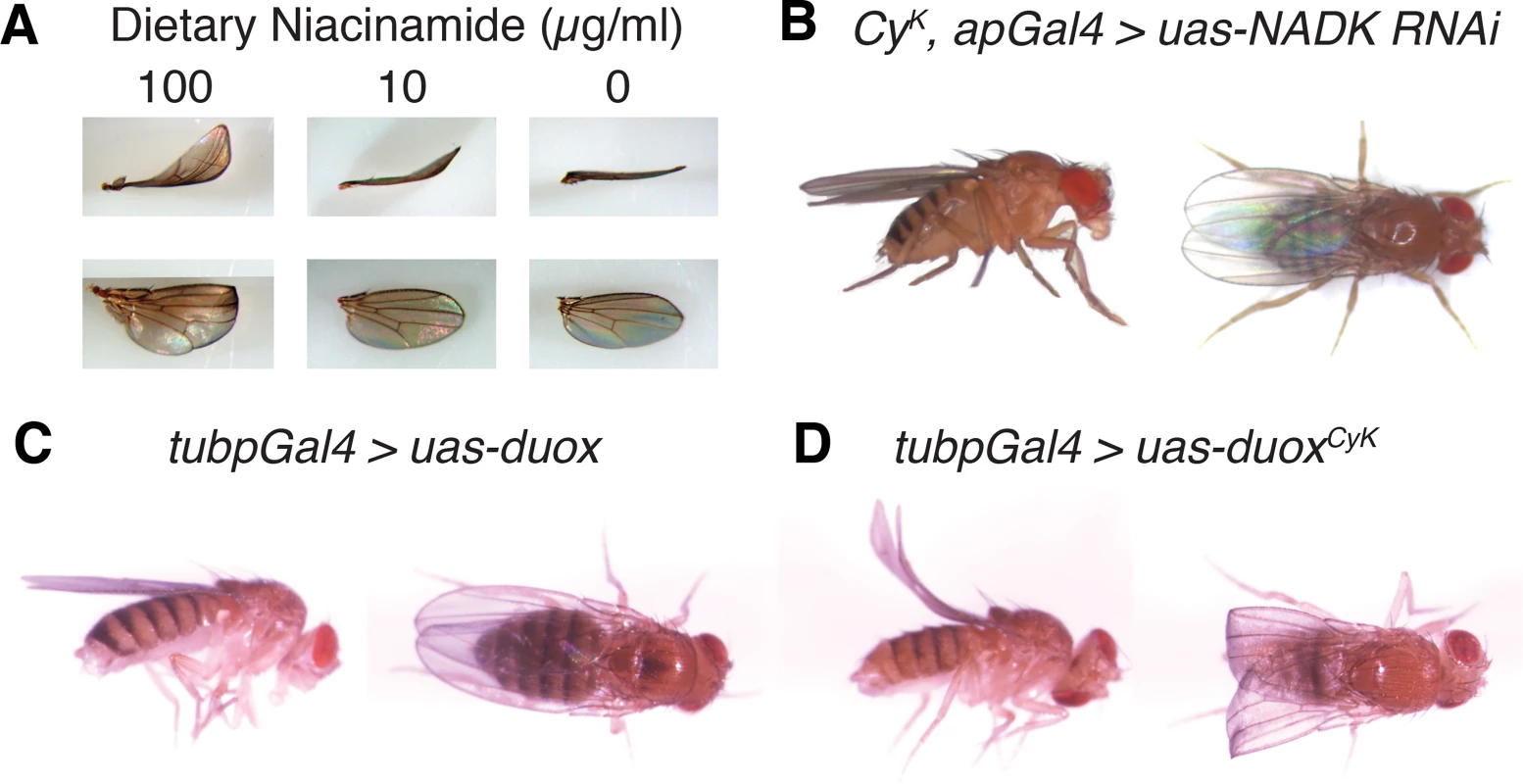

To further investigate the potential neomorphic nature of Curly mutations, we tested whether Curly mutations require NADPH, the substrate of Duox, to generate a wing phenotype. In the first instance, we attempted to alter the endogenous levels of NADPH by reducing the amount of niacinamide, a precursor of NADPH, in the diet of Curly flies. Interestingly, we found that a reduction of dietary niacinamide caused a dose-dependent decrease in the expressivity of the wing phenotype in Curly mutants (Fig 2A). To test this genetically, we next knocked down CG6145, which encodes a NAD+ kinase that phosphorylates NAD+ to generate NADP+ [15]. Specific knockdown of CG6145 in the wing using apterous-gal4 (apGal4) strongly suppressed the Curly wing phenotype (Fig 2B). Together these results suggest that Curly mutants require NADP+ and/or NADPH in order to cause changes in wing curvature. Therefore, not only do Curly mutations reduce Duox’s normal function, they also endow it with a new function that requires sufficient substrate to dominantly alter wing shape.

Fig. 2. Curly is likely a neomorphic allele of duox.

(A) Reduction of dietary niacinamide causes a dose-dependent decrease in the expressivity of the Curly wing phenotype. Flies were raised on food containing different concentrations of niacinamide. (B) Knockdown of the NAD+ kinase, CG6145, with the wing driver apGal4 suppresses the Curly wing phenotype. Knockdown of CG6145 with apGal4 alone did not cause a wing phenotype. (C) and (D) Ubiquitous expression of duoxCyK, but not duox, causes a Curly wing phenotype. UAS-duox and UAS-duoxCyK were expressed ubiquitously using the tubpGal4 driver. Duox is required autonomously in the wing during the last day of development to stabilize the wing

Having determined that Curly is most likely a neomophoric allele of duox, we decided to use Curly mutations to explore duox’s function in vivo in the wing. To do this, we generated a mutant form of duox, henceforth referred to as duoxCyK, in which glycine 1505 was mutated to a serine, as in the CyK mutant. In order to express duoxCyK conditionally we fused it to an Upstream Activating Sequence (UAS) element so that we could control its expression in a time-dependent and tissue-specific manner using the Gal4 system [16]. To demonstrate that this transgene was functional and able to recreate the Curly phenotype, we expressed it ubiquitously throughout the fly using tubpGal4 [17]. Indeed, ubiquitous expression of duoxCyK, but not wild-type duox, resulted in upward bent wings resembling those of CyK mutants (Fig 2C and 2D). This not only demonstrates that the duoxCyK transgene is functional, but also provides further evidence that Curly is an allele of duox.

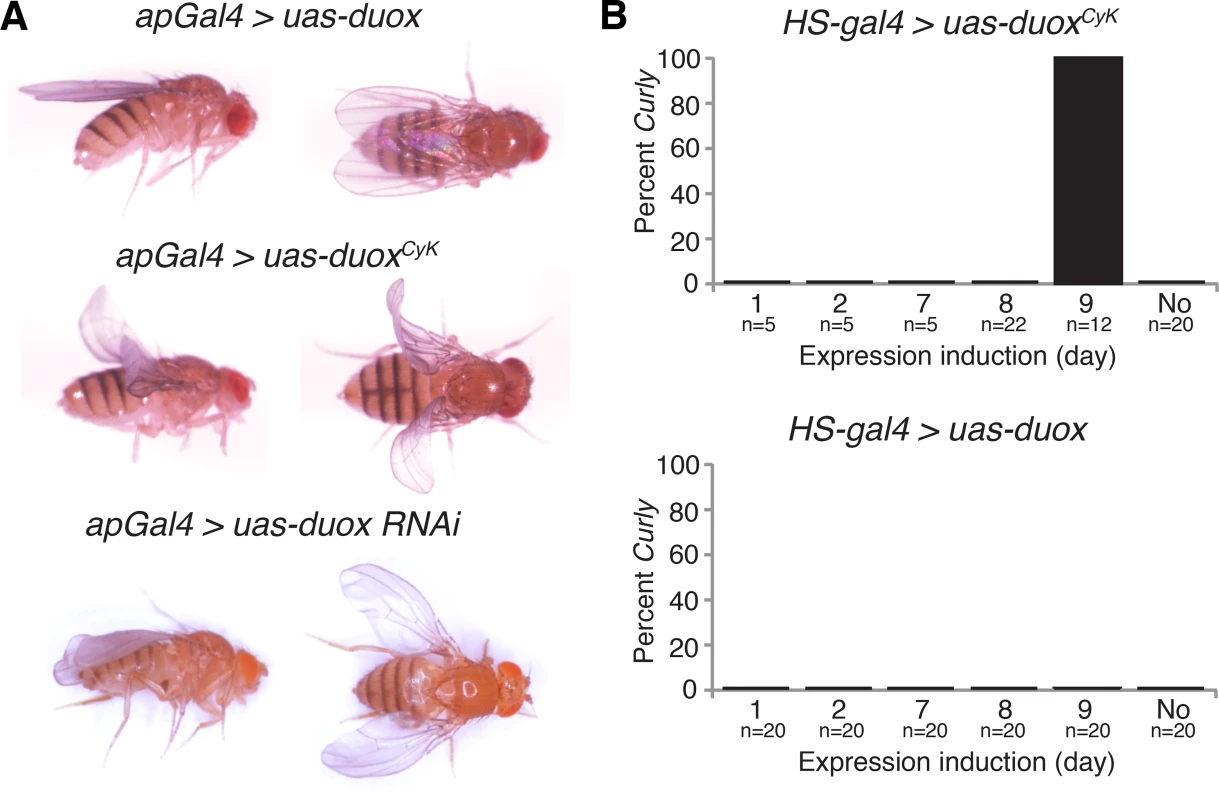

Duox could be required autonomously within the wing for its formation, or instead act non-autonomously in other tissues, as is the case for curled, a mutation that causes similar changes in wing morphology [2]. To determine where duox is required, we first expressed duoxCyK or duox RNAi in the wing using apGal4. Expression of duoxCyK, but not wild-type duox, caused the upward wing curvature, whereas knockdown of duox in the wing caused a slight downward curvature or cupping of the wing (Fig 3A). This demonstrates that duox is required autonomously in the wing for its formation.

Fig. 3. duox is required within the wing during the last day of development for wing stabilization.

(A) Expression of duoxCyK, but not duox, in the dorsal wing compartment causes a Curly phenotype. Knockdown of duox in the dorsal wing compartment causes downward cupping and bending of the wing. (B) Expression of duoxCyK but not wild-type duox on day 9 of development, but not before then, causes a Curly phenotype. Changes in wing curvature can be caused by differential growth between the dorsal and ventral wing surfaces, or could be caused by changes in cuticle structure [3, 4]. If duoxCyK were differentially influencing growth, we would expect it to be required early in pupal development, but not later, when proliferation and growth of the ventral and dorsal wing surfaces is largely complete [18]. To determine when in development duoxCyK is acting, we conditionally expressed it at various developmental stages using a heat shock-inducible driver. Expression of duoxCyK, but not duox, on the last day of pupal development, but not before then, resulted in upturned wings (Fig 3B). This suggests that Duox does not influence wing growth and instead perhaps plays a role in the formation of the wing cuticle. Taken together, our results demonstrate that duox acts autonomously in the wing to stabilize the cuticle during the last day of pupal development concurrent with the formation of the wing cuticle.

Duox works with the heme peroxidase Cysu to stabilize the wing

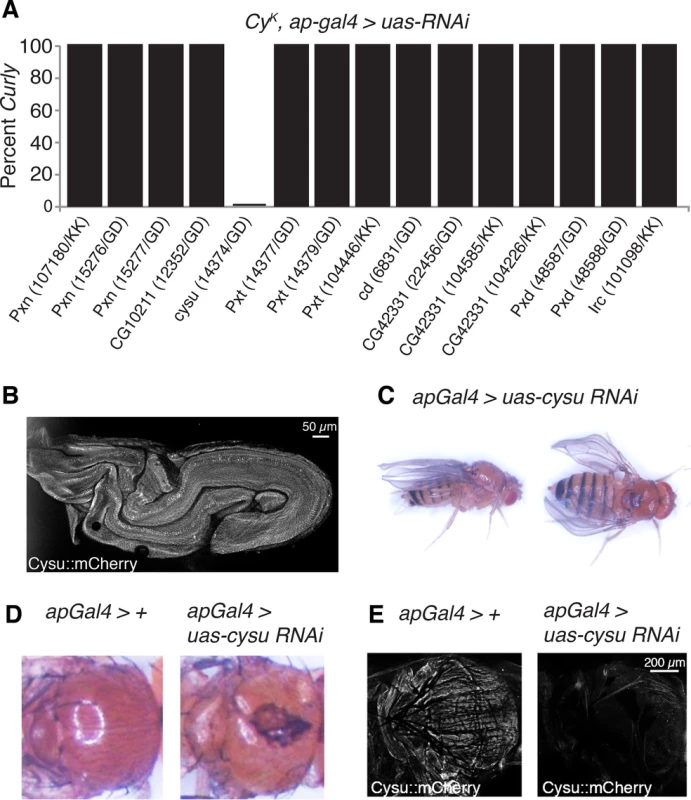

Hydrogen peroxide generated by NADPH oxidases is often used by peroxidases, most frequently heme peroxidases, to crosslink proteins and kill pathogens [6]. Heme peroxidases are essential for NADPH oxidase-dependent crosslinking reactions, but largely dispensable to their other functions [6]. To test whether Duox acts with a heme peroxidase in the wing to crosslink proteins and stabilize it, we individually knocked down all known D. melanogaster heme peroxidases (Fig 4A) [19] using RNAi in the wings of duoxCyK flies. If duoxCyK acts alone in the wing and does not participate in crosslinking reactions, then knockdown of heme peroxidases should not affect wing curvature. If, however, duoxCyK requires a heme peroxidase to function, then knockdown should suppress the Curly phenotype. Consistent with this, knockdown of one peroxidase, CG5873, fully suppressed the Curly phenotype in a manner resembling duox knockdowns, suggesting that Duox functions together with CG5873 to crosslink molecules to form the wing (Fig 4A). As CG5873 is a suppressor of Curly we have named it Curly Su, or cysu for short.

Fig. 4. The heme peroxidase Cysu works with Duox to stabilize the wing.

(A) Knockdown of cysu, but not the other seven Drosophila heme peroxidases, suppresses the Curly wing phenotype. (B) An endogenously tagged mCherry::Cysu is expressed in the late pupal wing. (C) Knockdown of Cysu in the dorsal wing compartment causes downward cupping and bending of the wing resembling Duox knockdown wings. (D) Knockdown of Cysu with apGal4 in a CyK background causes defects in scutellum and notum formation. (E) Cysu::mCherry is expressed in the thorax of control flies, but not those expressing cysu RNAi with apGal4. If cysu acts with duox to form the wing then one would expect it to: a) be expressed in the wing on the last day of development–the period in which Duox functions to form the wing; and b) have a similar phenotype to Duox when silenced in the wing. To test this first prediction, we generated a strain expressing endogenously mCherry-tagged Cysu. Consistent with Cysu functioning in the wing, we observed expression of mCherry-tagged Cysu in the wing on the last day of development using confocal microscopy (Fig 4B). To test our second prediction, we knocked down Cysu in the wing using RNAi. Cysu knockdown caused a slight downturning and cupping of the wing resembling Duox knockdown wings, further suggesting that Cysu and Duox function together to shape the wing (Fig 4C). Interestingly, defects in scutellum and notum formation were also observed in Duox and Cysu knockdowns, suggesting that they might play a broader role in cuticle formation (Fig 4D). Consistent with this, Cysu was expressed in the thorax of wild-type flies, but not Cysu knockdowns (Fig 4E). In summary, Duox and the heme peroxidase Cysu act together to stabilize the wing during development.

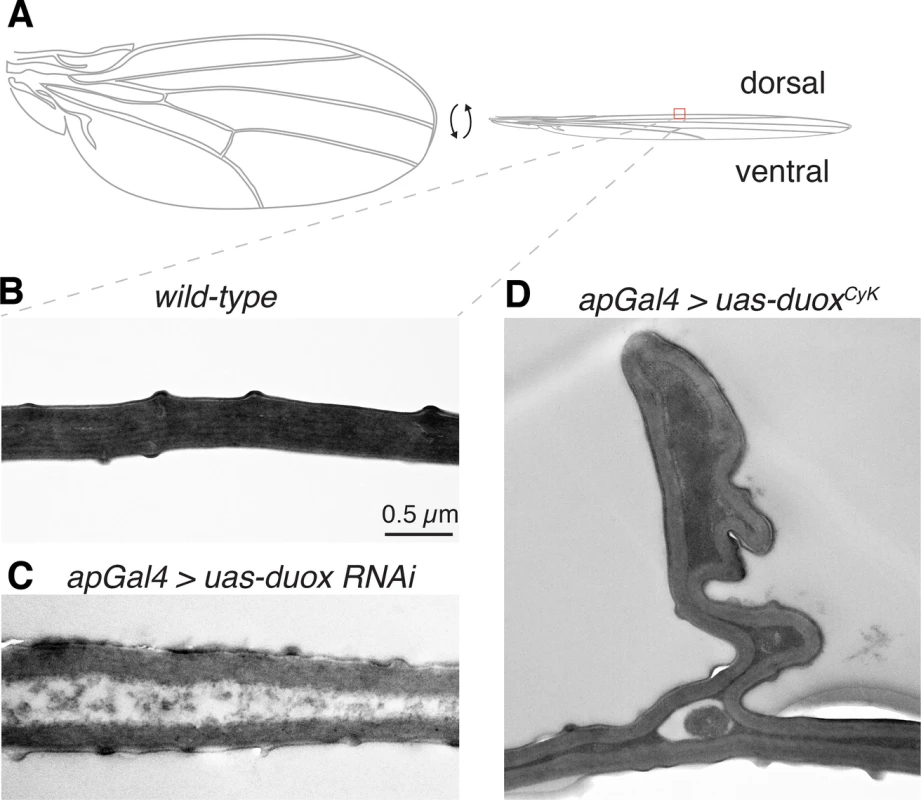

Duox is required for adhesion of the dorsal and ventral wing cuticles

The Drosophila adult wing is made up of two cuticle panels that are synthesized and secreted in a step-wise fashion by the dorsal and ventral ectodermal epithelial cells toward the end of pupal development [20, 21]. Upon eclosion, the dorsal and ventral cuticular surfaces of each wing expand and within an hour or so become bonded and adherent to one another [18]. To determine how altering Duox influences wing cuticle formation, we imaged wild-type and duox mutant wings using transmission electron microscopy (Fig 5). In wild-type wings, the ventral and dorsal cuticles are closely apposed and tightly bonded (Fig 5A). By contrast, in Duox knockdown wings the ventral and dorsal cuticles rarely directly contact one another, and instead are separated by a gap filled with disordered, electron poor material (Fig 5B). Interestingly, Curly mutant wings on the other hand appeared much more similar to wild-type wings with occasional abnormal bunching of the dorsal cuticle (Fig 5C). Whether this pinching and bunching reduces the surface area of the dorsal wing causing the wing to curve upward remains unknown. However, ultrastructure experiments clearly demonstrate a role for Duox in the adhesion and bonding of the two cuticle wing surfaces during wing formation.

Fig. 5. Duox is required for the adhesion and bonding of the dorsal and ventral wing cuticle panel.

(A) Cartoon of a wing. (B) In a wild-type wing, the dorsal and ventral cuticles are in close contact. (C) In duox knockdown wings, the dorsal and ventral cuticles are infrequently in direct contact. (D) In Curly wings, produced by expression of duoxCyK in the dorsal compartment of the wing with apGAL4, bunching of the dorsal wing surface can be observed. Discussion

Here we have shown that the Curly mutation arises in the NADPH-binding pocket encoding region of duox. Using Curly mutations and duox RNAi, we show that Duox is required within the wing to maintain its shape beginning on the last day of pupal development. Results from our genetic studies suggest Duox does this by supplying hydrogen peroxide to the heme peroxidase Cysu to facilitate the bonding of the two wing cuticle surfaces, likely by physically crosslinking them, during wing formation.

In all Curly mutants sequenced, a glycine residue, 1505, in the NADPH-binding pocket of Duox is mutated. This glycine is present in all NADPH oxidases from microbial eukaryotes to humans, and more broadly in oxidoreductase and ferric reductase NAD-binding domains (PFAM PF00175 and PF08030, respectively). Though mutagenesis studies have not been conducted on this residue itself, it sits beside an equally conserved cysteine residue, which has been studied in detail because mutations in it cause chronic granulomatous disease in humans [22]. This cysteine residue does not appear to be important for NADPH oxidase assembly or binding NADPH [22, 23]. Instead it is thought to be required for orienting bound NADPH for efficient electron transfer (via hydride) to FAD, and eventually oxygen [22]. Given glycine 1505’s proximity, it is possible that mutations in it similarly affect the transfer of electrons from NADPH to FAD. Consistent with this is the observation that Curly mutants are neither homozygous viable nor viable over a deficiency, suggesting that mutation of glycine 1505 causes a reduction in Duox’s normal function.

Although Curly mutations reduce Duox’s normal function, they also endow it with a new function. Precisely what this new function is remains obscure, however it likely requires a source of electrons because altering the NADPH/NADP+ by removing niacinamide from the food or knocking down NAD+ kinase suppressed the wing phenotype. It is known that the expressivity of the Curly wing phenotype can be suppressed by larval crowding and/or starving larvae [24]. Given this, it is possible that reduced uptake of niacinamide is a cause of the decreased expressivity of the Curly wing phenotype in starved larvae. Riboflavin shortage during the larval stage has also been suggested to be a cause of this suppression [2, 25]. Since riboflavin is a precursor of FAD, a co-factor also necessary for Duox’s function, it too may suppress the wing phenotype by reducing endogenous FAD and in turn reducing Duox’s activity. Regardless, Curly mutations are likely neomorphic and their sensitivity to environmental factors is likely mediated by changes in substrate availability.

Duox is required autonomously for wing stabilization. Results from this study and another strongly support this assertion [10]. Expression of duoxCyK or knockdown of duox on the last day prior to eclosion, but not earlier, caused defects in wing morphogenesis. This suggests that Duox and Curly do not influence growth or proliferation of the wing epithelia because these processes are complete by this time [18]. Instead, ultrastructural analysis suggests that Duox plays an important role in forming the cuticle of the wing. In duox knockdowns, frequent gaps between the two wing cuticle surfaces were observed, in contrast to the wild-type wings. Defects in adhesion of the two cuticle surfaces were also apparent in Curly mutants. Unlike wings from duox knockdowns, however, the cuticle surfaces in Curly wings were most often tightly apposed with occasional bunching of the dorsal surface. It is possible that in the Curly mutants this aberrant pinching of the dorsal surface decreases its area relative to the ventral surface causing the wing to bend, as first intimated by Waddington 75 years ago [3]. However, we do not know whether this is the cause of the curling or just a consequence of it.

Duox is known to be involved in the formation of extracellular matrices and cuticles [10–12]. Typically, it does this by supplying hydrogen peroxide to heme peroxidases, which use the hydrogen peroxide to perform crosslinking reactions. Consistent with Duox playing a role in crosslinking the cuticle we found that the heme peroxidase Cysu was essential for Duox function in the wing. Duox is unusual among NADPH oxidases in that it contains its own peroxidase homology domain, which in Caenorhabditis elegans and D. melanogaster has been proposed to fulfill the function of heme peroxidases, thereby obviating their need [7, 26, 27]. However, given that the peroxidase homology domain of Drosophila Duox lacks many amino acid residues, including the proximal and distal histidines, essential for efficient peroxidase function it is unclear how well it functions in this capacity [27]. Indeed, our results suggest that in D. melanogaster, Duox requires the heme peroxidase Cysu not only for stabilizing the wing cuticle, but also in the formation of the notum and scutellum. These findings point to a more general role for Duox and Cysu in cuticle formation.

In Drosophila, Duox has been intensely studied in the context of host defense and gut immunity. In the gut, Duox is thought to generate ROS to kill pathogens; flies that have reduced Duox activity have increased susceptibility to infection [7, 26]. Upon infection ROS generated by Duox kill pathogens, and possibly signal intestinal epithelial cells to proliferate and renew [7, 28]. Our results, as well as others, demonstrate that Duox is also critical in the formation of cuticle structures and extracellular matrices [10–12]. It is possible that Duox performs a similar function in the Drosophila intestine, perhaps by forming extracellular barriers or structures to protect against infection. Indeed, Duox in conjunction with heme peroxidases has been shown to form such barriers in guts of ticks and mosquitos [29, 30]. It would therefore be interesting to explore whether Duox and possibly Cysu are also involved in forming barriers to protect against infection in the Drosophila intestine.

Duox is an important protein that has a number of diverse functions, which we are only beginning to understand. Curly mutations provide an excellent opportunity to further explore Duox’s functions by identifying unknown interactors and regulators through unbiased genetic suppressor screens. The identification of Cysu through such an approach demonstrates its feasibility and utility. Such approaches will not only tell us about Duox’s function in the wing, but also about its role in immunity and beyond.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila husbandry and strains

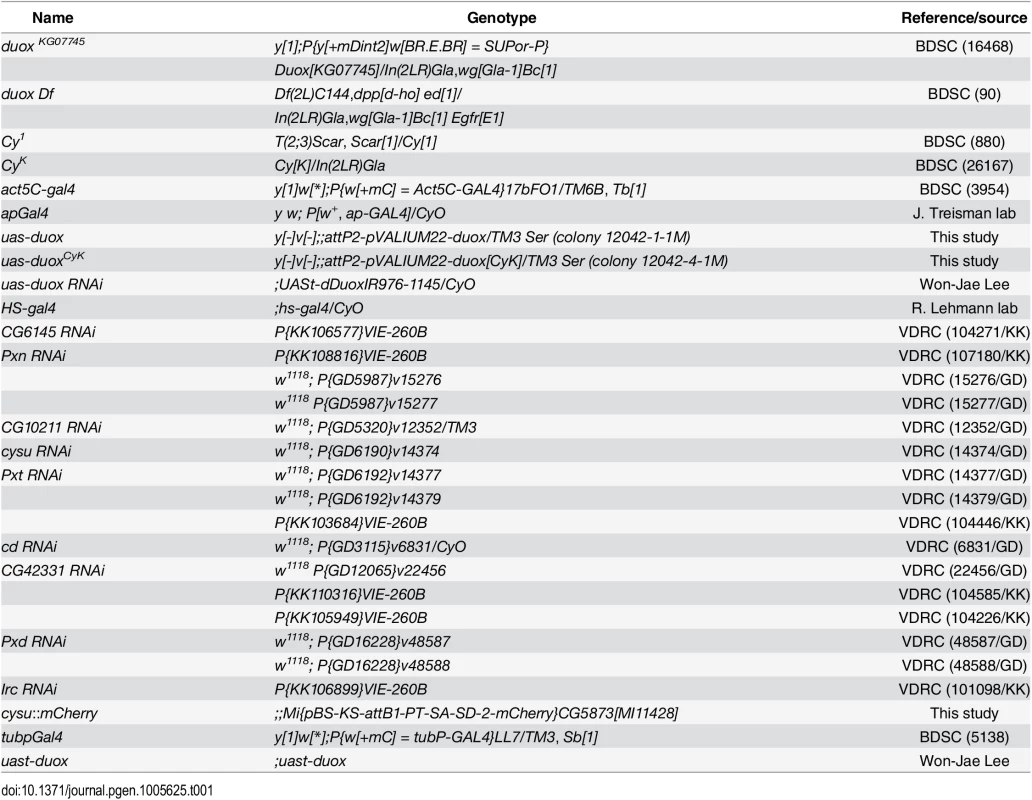

Flies were propagated in polystyrene vials (28.5 mm diameter) containing cornmeal molasses yeast medium at 25°C. For most crosses 5 virgin females were mated with 3 to 5 males. Fly strains used are shown in Table 1.

Tab. 1. <i>Drosophila</i> strains.

Conditional expression of duox and duoxCyK

duox and duoxCyK were conditionally expressed using a gal4 driver downstream of the heat-shock (HS) protein 70 promoter (HS-gal4). At various times during development Drosophila were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours to induce expression.

duoxKG07745 (BDSC 16468)

To verify the location of P{SUPor-P}DuoxKG07745 we performed inverse PCR. Consistent with the FlyBase report (FBal0226250) the 3’ flanking sequence was at genomic position 2L:2,826,884. However, unexpectedly, we found the 5’ flanking sequence to be at position 2L:2,755,447. This suggests that P{SUPor-P}DuoxKG07745 contains a deletion that perturbes 17 genes from Bacc to duox.

Generation of uas-duox and uas-duoxCyK strains

The duox open reading frame was amplified from cDNA and cloned into the pVALIUM22 vector [31] between XbaI and EcoRI restriction sites using standard methods. The CyK mutation was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit. Constructs were integrated into the attP2 site on the third chromosome using phiC31 integrase by BestGene.

Generation of Cysu::mCherry strain

mCherry-tagged Cysu expressing flies were made by BestGene by injecting mimic construct #1315 into Mi{MIC}CG5873MI11428 (BDSC 56608) [32].

DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was crudely isolated by homogenizing one to two flies in 0.2 mg/ml Proteinase K (Roche MC00079), 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and 25 mM NaCl and incubating for 25 min at 55°C. Proteinase K was subsequently inactivated by boiling the samples for 5 min. duox was then PCR amplified from genomic DNA and sequenced by Genewiz.

Niacinamide medium

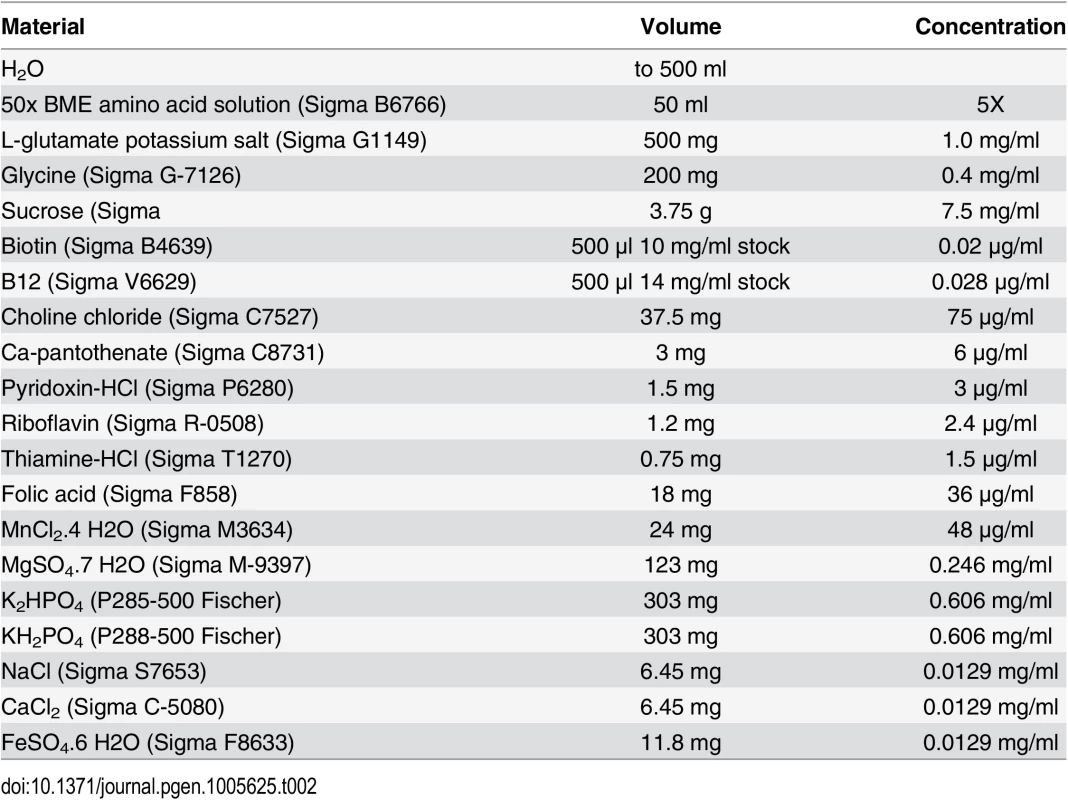

Flies were raised on a defined medium with various concentration of niacinamide from embryo to adult. A solution was prepared as described in Table 2 and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH. 20 mg/ml agar yeast culture grade (Sunrise Science Products 1910) was dissolved in the solution by heating before adding 0.4 mg/ml cholesterol (Sigma C3045) and niacinamide (Sigma N0636).

Imaging

Fluorescent images were acquired with a 10X/NA objective on a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope. All other images were obtained with a Zeiss SteREO Discovery.V8 microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy, whole flies were immersed in 95% ethanol briefly to get rid of any air bubbles, decapitated and immersed into fixative containing 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M PIPES buffer, pH 7.2 at room temperature for 2 hours, and then overnight at 4°C. Flies were next embedded in 1% agar and post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide with 1.5% potassium ferricyanide in 0.1M PIPES buffer for 1 hour then en block stained with 1% uranyl acetate in ddH2O at 4°C overnight. Samples were dehydrated with ethanol at room temperature before incubation with propylene oxide and embedment in Spurr resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). 500nm semi-thin sections were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue to evaluate the area of interest. 60nm ultrathin sections were cut, mounted on formvar coated slotted copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate by standard methods. Stained grids were examined under Philips CM-12 electron microscope (FEI; Eindhoven, The Netherlands) and photographed with a Gatan (4k x2.7k) digital camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Ward L. The Genetics of Curly Wing in Drosophila. Another Case of Balanced Lethal Factors. Genetics. 1923;8(3):276–300. 17246014

2. Gronke S, Bickmeyer I, Wunderlich R, Jackle H, Kuhnlein RP. Curled encodes the Drosophila homolog of the vertebrate circadian deadenylase Nocturnin. Genetics. 2009;183(1):219–32. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.105601 19581445

3. Waddington C. The genetic control of wing development in Drosophila. Journal of Genetics. 1940;41 : 75–139.

4. Lee JH, Budanov AV, Park EJ, Birse R, Kim TE, Perkins GA, et al. Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies. Science. 2010;327(5970):1223–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1182228 20203043

5. Sturtevant AH, Novitski E. The Homologies of the Chromosome Elements in the Genus Drosophila. Genetics. 1941;26(5):517–41. 17247021

6. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiological reviews. 2007;87(1):245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005 17237347

7. Kim SH, Lee WJ. Role of DUOX in gut inflammation: lessons from Drosophila model of gut-microbiota interactions. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2014;3 : 116. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00116 24455491

8. De Deken X, Wang D, Many MC, Costagliola S, Libert F, Vassart G, et al. Cloning of two human thyroid cDNAs encoding new members of the NADPH oxidase family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(30):23227–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000916200 10806195

9. Dupuy C, Ohayon R, Valent A, Noel-Hudson MS, Deme D, Virion A. Purification of a novel flavoprotein involved in the thyroid NADPH oxidase. Cloning of the porcine and human cdnas. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(52):37265–9. 10601291

10. Anh NT, Nishitani M, Harada S, Yamaguchi M, Kamei K. Essential role of Duox in stabilization of Drosophila wing. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(38):33244–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263178 21808060

11. Edens WA, Sharling L, Cheng G, Shapira R, Kinkade JM, Lee T, et al. Tyrosine cross-linking of extracellular matrix is catalyzed by Duox, a multidomain oxidase/peroxidase with homology to the phagocyte oxidase subunit gp91phox. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(4):879–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103132 11514595

12. Wong JL, Creton R, Wessel GM. The oxidative burst at fertilization is dependent upon activation of the dual oxidase Udx1. Dev Cell. 2004;7(6):801–14. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.014 15572124

13. Littleton JT, Bellen HJ. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of thirteen essential genes in cytological interval 22F1-2; 23B1-2 reveals novel genes required for neural development in Drosophila. Genetics. 1994;138(1):111–23. 8001779

14. Cook K. Mutations from Jim Kennison. In: FlyBase, editor. http://flybase.org/reports/FBrf0206482.html2008.

15. Magni G, Orsomando G, Raffaelli N. Structural and functional properties of NAD kinase, a key enzyme in NADP biosynthesis. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6(7):739–46. 16842123

16. Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118(2):401–15. 8223268

17. Bello BC, Hirth F, Gould AP. A pulse of the Drosophila Hox protein Abdominal-A schedules the end of neural proliferation via neuroblast apoptosis. Neuron. 2003;37(2):209–19. 12546817

18. Kiger JA Jr., Natzle JE, Kimbrell DA, Paddy MR, Kleinhesselink K, Green MM. Tissue remodeling during maturation of the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2007;301(1):178–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.011 16962574

19. Hughes AL. Evolution of the Heme Peroxidases of Culicidae (Diptera). Psyche. 2012;2012.

20. Moussian B. Recent advances in understanding mechanisms of insect cuticle differentiation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40(5):363–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.03.003 20347980

21. Doctor J, Fristrom D, Fristrom JW. The pupal cuticle of Drosophila: biphasic synthesis of pupal cuticle proteins in vivo and in vitro in response to 20-hydroxyecdysone. J Cell Biol. 1985;101(1):189–200. 3891759

22. Debeurme F, Picciocchi A, Dagher MC, Grunwald D, Beaumel S, Fieschi F, et al. Regulation of NADPH oxidase activity in phagocytes: relationship between FAD/NADPH binding and oxidase complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(43):33197–208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151555 20724480

23. Aliverti A, Piubelli L, Zanetti G, Lubberstedt T, Herrmann RG, Curti B. The role of cysteine residues of spinach ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase As assessed by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1993;32(25):6374–80. 8518283

24. Nozawa K. The effects of the environmental conditions on Curly expressivity in Drosophila melanogaster. The Japanese Journal of Genetics. 1965;31(6):163–71.

25. Pavelka J, Jindrak L. Mechanism of the fluorescent light induced suppression of Curly phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster. Bioelectromagnetics. 2001;22(6):371–83. 11536279

26. Ha EM, Oh CT, Bae YS, Lee WJ. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science. 2005;310(5749):847–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1117311 16272120

27. Meitzler JL, Brandman R, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Perturbed heme binding is responsible for the blistering phenotype associated with mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans dual oxidase 1 (DUOX1) peroxidase domain. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(52):40991–1000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.170902 20947510

28. Buchon N, Broderick NA, Chakrabarti S, Lemaitre B. Invasive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2009;23(19):2333–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.1827009 19797770

29. Kumar S, Molina-Cruz A, Gupta L, Rodrigues J, Barillas-Mury C. A peroxidase/dual oxidase system modulates midgut epithelial immunity in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2010;327(5973):1644–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1184008 20223948

30. Yang X, Smith AA, Williams MS, Pal U. A dityrosine network mediated by dual oxidase and peroxidase influences the persistence of Lyme disease pathogens within the vector. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(18):12813–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.538272 24662290

31. Ni JQ, Liu LP, Binari R, Hardy R, Shim HS, Cavallaro A, et al. A Drosophila resource of transgenic RNAi lines for neurogenetics. Genetics. 2009;182(4):1089–100. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103630 19487563

32. Venken KJ, Schulze KL, Haelterman NA, Pan H, He Y, Evans-Holm M, et al. MiMIC: a highly versatile transposon insertion resource for engineering Drosophila melanogaster genes. Nat Methods. 2011;8(9):737–43. 21985007

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin TransporterČlánek Exocyst-Dependent Membrane Addition Is Required for Anaphase Cell Elongation and Cytokinesis inČlánek Spindle-F Is the Central Mediator of Ik2 Kinase-Dependent Dendrite Pruning in Sensory Neurons

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 11- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

- Mateřský haplotyp KIR ovlivňuje porodnost živých dětí po transferu dvou embryí v rámci fertilizace in vitro u pacientek s opakujícími se samovolnými potraty nebo poruchami implantace

- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Doc. Miloš Kubánek: Nemocní se srdeční amyloidózou jsou často skryti a sledováni pod jinými diagnózami

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Agricultural Genomics: Commercial Applications Bring Increased Basic Research Power

- Ernst Rüdin’s Unpublished 1922-1925 Study “Inheritance of Manic-Depressive Insanity”: Genetic Research Findings Subordinated to Eugenic Ideology

- Convergent Evolution During Local Adaptation to Patchy Landscapes

- The Locus Controls Age at Maturity in Wild and Domesticated Atlantic Salmon ( L.) Males

- A Hereditary Enteropathy Caused by Mutations in the Gene, Encoding a Prostaglandin Transporter

- Absence of Maternal Methylation in Biparental Hydatidiform Moles from Women with Maternal-Effect Mutations Reveals Widespread Placenta-Specific Imprinting

- Calibrating the Human Mutation Rate via Ancestral Recombination Density in Diploid Genomes

- Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Acts in the Mushroom Body to Negatively Regulate Sleep

- Connecting Replication and Repair: YoaA, a Helicase-Related Protein, Promotes Azidothymidine Tolerance through Association with Chi, an Accessory Clamp Loader Protein

- UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

- Mosaic and Intronic Mutations in Explain the Majority of TSC Patients with No Mutation Identified by Conventional Testing

- Members of the Epistasis Group Contribute to Mitochondrial Homologous Recombination and Double-Strand Break Repair in

- QTL Mapping of Sex Determination Loci Supports an Ancient Pathway in Ants and Honey Bees

- Genetic Interactions Implicating Postreplicative Repair in Okazaki Fragment Processing

- Genomics of Cancer and a New Era for Cancer Prevention

- Adaptation to High Ethanol Reveals Complex Evolutionary Pathways

- Dynamics of Transcription Factor Binding Site Evolution

- Exocyst-Dependent Membrane Addition Is Required for Anaphase Cell Elongation and Cytokinesis in

- Enhancer Runaway and the Evolution of Diploid Gene Expression

- Cattle Sex-Specific Recombination and Genetic Control from a Large Pedigree Analysis

- Drosophila Mutants Model Cornelia de Lange Syndrome in Growth and Behavior

- Pleiotropic Effects of Immune Responses Explain Variation in the Prevalence of Fibroproliferative Diseases

- Leaderless Transcripts and Small Proteins Are Common Features of the Mycobacterial Translational Landscape

- Tissue-Specific Effects of Reduced β-catenin Expression on Mutation-Instigated Tumorigenesis in Mouse Colon and Ovarian Epithelium

- Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin

- Mapping of Craniofacial Traits in Outbred Mice Identifies Major Developmental Genes Involved in Shape Determination

- Conserved Genetic Interactions between Ciliopathy Complexes Cooperatively Support Ciliogenesis and Ciliary Signaling

- Metabolomic Quantitative Trait Loci (mQTL) Mapping Implicates the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

- DNA Repair Cofactors ATMIN and NBS1 Are Required to Suppress T Cell Activation

- Spindle-F Is the Central Mediator of Ik2 Kinase-Dependent Dendrite Pruning in Sensory Neurons

- Ernst Rüdin and the State of Science

- ABCs of Insect Resistance to Bt

- Epigenetic Control of O-Antigen Chain Length: A Tradeoff between Virulence and Bacteriophage Resistance

- Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

- The Fanconi Anemia Pathway Protects Genome Integrity from R-loops

- Controls Quantitative Variation in Maize Kernel Row Number

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Golden Retrievers Identifies Germ-Line Risk Factors Predisposing to Mast Cell Tumours

- Insect Resistance to Toxin Cry2Ab Is Conferred by Mutations in an ABC Transporter Subfamily A Protein

- A Cytosine Methytransferase Modulates the Cell Envelope Stress Response in the Cholera Pathogen

- Conserved piRNA Expression from a Distinct Set of piRNA Cluster Loci in Eutherian Mammals

- The Multi-allelic Genetic Architecture of a Variance-Heterogeneity Locus for Molybdenum Concentration in Leaves Acts as a Source of Unexplained Additive Genetic Variance

- The lncRNA Controls Cryptococcal Morphological Transition

- Sae2 Function at DNA Double-Strand Breaks Is Bypassed by Dampening Tel1 or Rad53 Activity

- A Tandem Duplicate of Anti-Müllerian Hormone with a Missense SNP on the Y Chromosome Is Essential for Male Sex Determination in Nile Tilapia,

- Ectodysplasin/NF-κB Promotes Mammary Cell Fate via Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

- The QTL within the Complex Involved in the Control of Tuberculosis Infection in Mice Is the Classical Class II Gene

- Identifying Loci Contributing to Natural Variation in Xenobiotic Resistance in

- Variation in Rural African Gut Microbiota Is Strongly Correlated with Colonization by and Subsistence

- A Flexible, Efficient Binomial Mixed Model for Identifying Differential DNA Methylation in Bisulfite Sequencing Data

- Competition between Heterochromatic Loci Allows the Abundance of the Silencing Protein, Sir4, to Regulate Assembly of Heterochromatin

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development

- Metabolomic Quantitative Trait Loci (mQTL) Mapping Implicates the Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Cardiovascular Disease Pathogenesis

- Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin

- Encodes Dual Oxidase, Which Acts with Heme Peroxidase Curly Su to Shape the Adult Wing

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání