-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaGenetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

Contributions of null and hypomorphic alleles of Apc in mice produce both developmental and pathophysiological phenotypes. To ascribe the resulting genotype-to-phenotype relationship unambiguously to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, we challenged the allele combinations by genetically restricting intracellular β-catenin expression in the corresponding compound mutant mice. Subsequent evaluation of the extent of resulting Tcf4-reporter activity in mouse embryo fibroblasts enabled genetic measurement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the form of an allelic series of mouse mutants. Different permissive Wnt signaling thresholds appear to be required for the embryonic development of head structures, adult intestinal polyposis, hepatocellular carcinomas, liver zonation, and the development of natural killer cells. Furthermore, we identify a homozygous Apc allele combination with Wnt/β-catenin signaling capacity similar to that in the germline of the Apcmin mice, where somatic Apc loss-of-heterozygosity triggers intestinal polyposis, to distinguish whether co-morbidities in Apcmin mice arise independently of intestinal tumorigenesis. Together, the present genotype–phenotype analysis suggests tissue-specific response levels for the Wnt/β-catenin pathway that regulate both physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 6(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000816

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000816Summary

Contributions of null and hypomorphic alleles of Apc in mice produce both developmental and pathophysiological phenotypes. To ascribe the resulting genotype-to-phenotype relationship unambiguously to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, we challenged the allele combinations by genetically restricting intracellular β-catenin expression in the corresponding compound mutant mice. Subsequent evaluation of the extent of resulting Tcf4-reporter activity in mouse embryo fibroblasts enabled genetic measurement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the form of an allelic series of mouse mutants. Different permissive Wnt signaling thresholds appear to be required for the embryonic development of head structures, adult intestinal polyposis, hepatocellular carcinomas, liver zonation, and the development of natural killer cells. Furthermore, we identify a homozygous Apc allele combination with Wnt/β-catenin signaling capacity similar to that in the germline of the Apcmin mice, where somatic Apc loss-of-heterozygosity triggers intestinal polyposis, to distinguish whether co-morbidities in Apcmin mice arise independently of intestinal tumorigenesis. Together, the present genotype–phenotype analysis suggests tissue-specific response levels for the Wnt/β-catenin pathway that regulate both physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Introduction

The evolutionarily conserved Wnt/β-catenin pathway is a critical regulator of proliferation and differentiation and plays a pivotal role during embryonic development and in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis in the adult. A multitude of studies have documented that impaired or excessive activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway result in a large number of pathophysiological conditions, including cancer (for review see [1]). Tight regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is ensured by compartmentalized expression of the different Wnt ligands and receptor components and this is complemented by multiple layers of negative regulation. In particular, the tumor suppressor protein Apc provides a platform for the formation of a β-catenin destruction complex, and thereby acts as a negative regulator of activated Wnt signaling. Loss of Apc function leads to ligand-independent accumulation of β-catenin and its nuclear translocation, where it binds to Tcf/Lef family transcription factors and induces expression of target genes such as Axin2, Cyclin D1 and c-Myc that are involved in proliferation and transformation (for review see [2]).

During embryonic development, Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an important role in the anterior-posterior patterning of the primary embryonic axis in vertebrates. Unregulated activity of the Wnt pathway during embryonic development leads to anterior defects. For example in mice, loss of Dkk1, a Wnt antagonist, results in truncation of head structures anterior to the mid-hindbrain boundary [3] and mice doubly deficient for the Wnt antagonists Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 have a shortened anterior-posterior axis [4]. Ectopic expression of Wnt8C in mice causes axis duplication and severe anterior truncations [5], while embryos lacking functional β-catenin have impaired anterior-posterior axis formation [6]. Embryos homozygous for the mutant Apcmin allele, which results in truncation of the full-length 2843 amino acid protein at residue 850 and in heterozygous mice leads to an intestinal phenotype akin to familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) in humans, fail to develop past the gastrulation stage due to proximalisation of the epiblast and ectopic activation of several posterior mesendodermal genes [7],[8]. While these observations establish indispensable roles for components of the Wnt pathway in patterning the anterior-posterior axis, recent genetic rescue studies have helped to define signaling threshold requirement(s) for head morphogenesis [9].

Mutations in components of the destruction complex (APC, AXIN, GSK3β etc) are implicated in tumorigenesis and result in aberrant, ligand-independent activation of the WNT/β-CATENIN pathway. For instance truncating nonsense mutations in APC, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or promoter hypermethylation are most prominently associated with aberrant WNT signaling that is characteristic of more than 90% of sporadic forms of colorectal cancer in humans [10]–[12]. Meanwhile epigenetic and genetic impairment mutations that reduce expression of wild-type AXIN2/CONDUCTIN [13],[14] or amino-terminal missense mutations in CTNNB1 (β-CATENIN) [15] are most commonly associated with aberrant WNT signaling in cancers of the liver (hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatoblastoma), stomach, kidney (Wilms tumor) and ovaries. It remains unclear why in humans the intestinal epithelium is most sensitive to cancer-associated somatic mutations in APC rather than to those in other components of the WNT signaling cascade, and to what extent this may be due to the loss of interaction between APC and actin-regulatory proteins and microtubules that affect cell migration, orientation, polarity, division and apoptosis, rather than the proliferation/differentiation generally associated with WNT/β-CATENIN signaling (for review see [16]). However, at least in the mouse the C–terminal domains of Apc are dispensable for its tumor suppressing functions [17]. In addition, phenotypic changes observed after the conditional deletion of Apc including those on apoptosis, migration, differentiation and proliferation are rescued by concomitant deletion of the Wnt/β-catenin target gene Myc [18].

Signaling threshold levels in vivo have been assessed by various approaches, including administration of (ant-) agonistic compounds, the (inducible) over-expression of transgenes and the creation of haploinsufficiency through the combination of knock-out and hypomorphic alleles. Elegant combinations of different hypomorphic Apc alleles, for instance, have demonstrated that within the context of intestinal tumorigenesis, there is a clear correlation between gene dosage and phenotype severity [17],[19]. In particular, these studies implied an inverse correlation between the level of Apc protein expression and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and in turn, proliferation and differentiation of epithelium along the crypt-villus axis as well as cell renewal in the stem cell compartment [20]. Here we genetically identify differences in signaling threshold levels that determine physiological and pathological outcomes during embryonic development and various aspects of tissue homeostasis in adult tissue. Using combinations of epistatically related hypomorphic alleles of components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade, we identify tissue-specific signaling threshold levels for anterior specification during embryogenesis, intestinal and hepatic homeostasis in the adult. Our observations add further support to the “just-right” model [21] of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation where distinct dosages are required to perturb the self-renewal of stem cell populations and lead to neoplastic transformation in the intestine and liver.

Results/Discussion

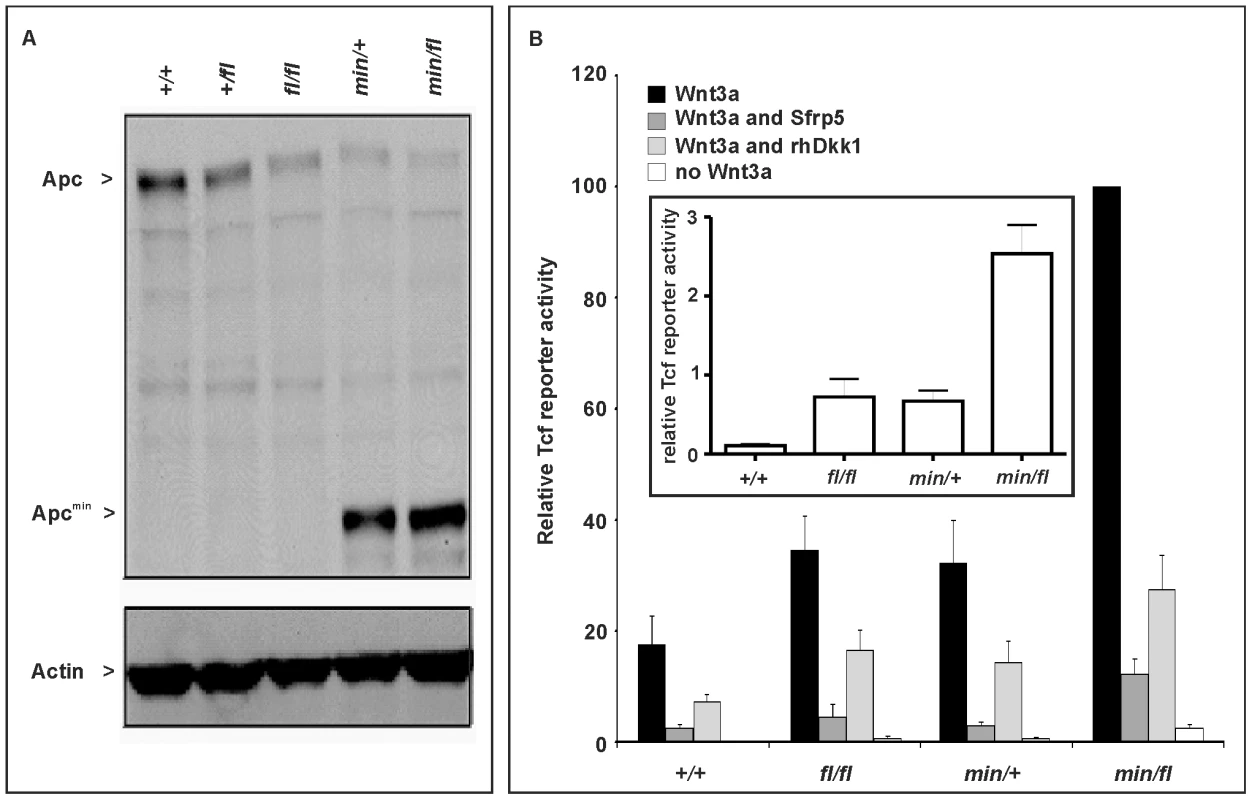

Genetic modulation of full-length Apc expression in mouse embryonic fibroblasts

In order to modulate the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the mouse, we took advantage of the Apcmin [22] and Apcfl [23] alleles. The premature stop codon encoded by the Apcmin allele encodes a truncated 850 amino acid Apc protein, which lacks the 15 - and 20 aa repeats and Axin binding repeats required for β-catenin regulation [24], while the unrecombined Apcfl allele results in attenuated expression levels of wild-type Apc mRNA [23]. We used Western blot analysis of lysates from mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) to quantitate expression of full-length Apc protein and the capacity to augment Wnt3a-dependent signaling in cells from the corresponding Apc allele combinations. We observed an inverse relationship in the hierarchy of allele combinations between full-length Apc protein expression (Figure 1A), and signaling activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway recorded with a Tcf4 reporter plasmid (Figure 1B). Owing to the presence of residual amounts of full-length Apc protein, the two soluble Wnt antagonists Sfrp5 and Dkk1 were able to suppress Wnt3a-mediated reporter activation in cells of all tested allele combinations. However, in the presence of Wnt3a, pSUPERTopFlash reporter activity was inhibited less effectively by Sfrp5 and Dkk1 in cells with impaired expression of full-length Apc protein (Figure 1B). Therefore, genetic modulation of the expression levels of full-length Apc protein enables experimental manipulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation for a given concentration of Wnt ligand or its soluble antagonists.

Fig. 1. Apc protein expression levels and Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs).

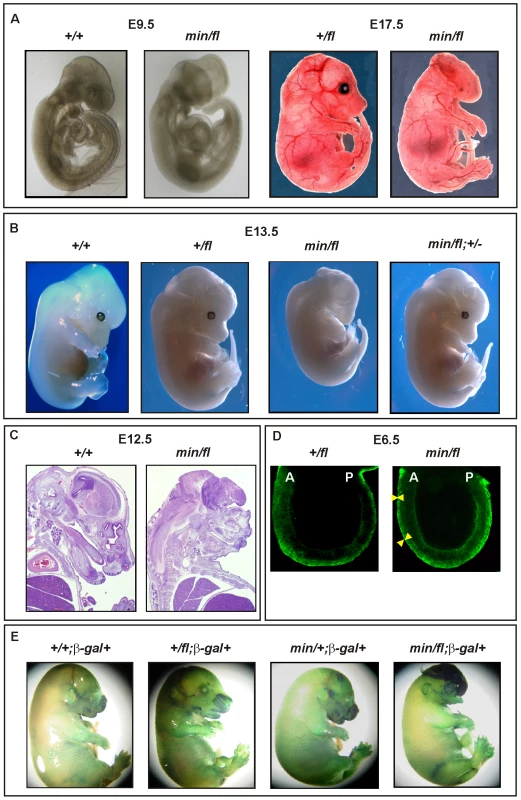

(A) Immunoblot analysis of MEF lysates prepared from mice of the indicated genotype were used to detect full-length (Apc) and mutant (Apcmin) protein using β-actin as loading control. (B) Tcf4 reporter activity in response to Wnt3a in the presence or absence of the antagonists Dkk1 or Sfrp5. Activity was assessed following transient transfection of the pSuperTopFlash reporter plasmid. Where indicated, cells were cotransfected with an expression plasmid encoding Sfrp5, and stimulated with recombinant human Dkk1 and conditioned medium from cells expressing Wnt3a. Cultures were harvested 48h later and assayed for luciferase activity using the dual luciferase system and reporter activity in (min/fl) MEF exposed to a submaximal Wnt3a stimulation was arbitrarily set to 100. At least two independent experiments were performed in triplicates for each genotype. The insert shows relative Tcf4 reporter activation in the absence of stimulation with Wnt3a ligand. Mean ± SD. Genotypes are as follows: wild-type (+/+); Apc+/fl (+/fl); Apcfl/fl (fl/fl); Apcmin/+ (min/+); Apcmin/fl (min/fl). All MEFs were derived from mice on a mixed genetic 129Sv x C57BL/6 background. To assess whether the outcome of incremental modulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by genetic means in MEFs would impact differentially during development and in adult tissue homeostasis in vivo, we set out to generate adult mutant mice with genotypes comprising different combinations of Apc alleles. Surprisingly, we were unable to obtain Apcmin/fl mice at term from crossing heterozygous Apc+/fl with Apcmin/+ mice. Since homozygous Apcmin, but not Apcfl, mice die in utero due to gastrulation defects [7], we genotyped 117 embryos at E12 and found that all 30 Apcmin/fl embryos lacked all structures anterior to the hindbrain. Anterior morphological defects first became visible in E8.5-E9.5 Apcmin/fl embryos, and remained restricted to that region throughout embryonic development (Figure 2A and 2B). Histological cross-sections of Apcmin/fl E12 embryos revealed the presence of a prominent cap of neural tissue that formed at the most anterior part of the embryo, in the absence of cranial structures and the mandible (Figure 2C). Next we used the BAT::gal reporter allele to confirm excessive Tcf4-dependent β-galactosidase reporter activity in the neural tissue cap of Apcmin/fl E15 embryos. As predicted from the Tcf-reporter analysis in MEFs, we also observed BAT::gal reporter activity around the fronto-nasal region with a gradual increase from Apc+/+ to Apc+/fl and Apcmin/+ embryos. This was further extended to most abnormal anterior structures in the Apcmin/fl embryos (Figure 2E). Furthermore, analysis of E5.5-E7.5 embryos by wholemount confocal immunohistochemistry revealed anterior extension of β-catenin expression in the anterior visceral endoderm, an axial signaling centre in the outer endoderm layer of early embryos [8],[25], of Apcmin/fl embryos when compared to their Apc+/fl counterparts (Figure 2D). However, “headless” Apcmin/fl embryos were present at the expected Mendelian ratios until E15.5 (Table S1A) and live embryos could still be detected at E17.5 (Theiler stage 25–26) (Figure 2A) but at less than the expected Mendelian ratio. Our observations therefore support a role for limiting Apc-dependent signaling) functions during the development and patterning of the most anterior structures of the embryo similar to that proposed for excessive Wnt3 signaling in Dkk1-deficient or compound mutant Dkk1+/−;Wnt3+/− mice [9],[20], and reminiscent of the function played by Otx2 [26].

Fig. 2. Excessive Wnt/β-catenin signaling results in anterior head defects during embryonic development.

(A) Whole mounts of E9.5 (+/+) and (min/fl) mutant embryos and E17.5 (+/fl) and (min/fl) mutant embryos. (B) Whole mounts of E13.5 wild-type and mutant embryos of the indicated genotypes. Genetic ablation of one allele of β-catenin in (min/fl) “headless” mutant rescues normal head morphology in (min/fl; +/−) mice. (C) Histological cross sections of E12 wild-type (+/+) and mutant (min/fl) embryos. (D) Confocal cross section of E3.5–5.5 (+/fl) and (min/fl) embryos stained for β-catenin protein. The arrowheads demarcate the outer layer (anterior visceral endoderm) of the embryo which shows increased and expanded β-catenin expression in the (min/fl) mutant. A, Anterior; P, Posterior. (E) Whole mount in vivo X-gal staining of E16 embryos to monitor canonical Wnt/β-catenin dependent activity in compound mutant mice harboring the corresponding BAT::gal reporter transgene. Genotypes are as follows: wild-type (+/+); Apc+/fl (+/fl); Apcfl/fl (fl/fl); Apcmin/+ (min/+); Apcmin/fl (min/fl); Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (min/fl; +/−). All mice were on a mixed genetic 129Sv x C57BL/6 background. To establish that the “headless” phenotype in Apcmin/fl mice arose from altering the extent of Wnt/β-catenin signaling rather than arising from other potentially dominant-negative activities mediated by the truncated Apcmin protein, we conducted three further genetic experiments. First, we created a more severely 580 amino acid truncated Apc protein by excising exon 14 in Apc+/fl mice that were crossed with the CMV:Cre deletor strain to induce a germline nonsense frame-shift mutation in the corresponding recombined Apc580Δ allele. Subsequent matings of Cre-transgene-negative Apc580Δ/+ mice with Apc+/fl mice failed to yield Apc580Δ/fl pups at birth (Table S1B). Meanwhile, inspection of E9.5, E12 and E16 litters revealed that approximately 25% of all embryos displayed a “headless” phenotype indistinguishable from that observed in stage-matched Apcmin/fl mice (data not shown).

Second, we attempted to rescue the “headless” phenotype in Apcmin/fl mice by genetically limiting expression of β-catenin in corresponding Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− compound mutant mice. Resulting Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− MEFs revealed an approximately 50% reduction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling when compared to their Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/+ counterparts (see below). When mating Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/− with Apcmin/+;Ctnnb1+/+ mice, we recovered Apc+/fl;Ctnnb1+/+, Apc+/fl;Ctnnb1+/− and Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice at weaning age at a similar ratio, while among E13.5 embryos, all four possible genotypes were represented at comparable frequencies (Table S1C and Figure S1). Importantly, Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice developed normally into fecund adults (Figure 2B and data not shown), suggesting that limiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling corrected the development of detrimental phenotypes observed in Apcmin/fl mice.

Since the atypical Wnt receptor component Ryk has recently been suggested to amplify Wnt signaling during cortical neurogenesis through β-catenin-dependent as well as independent pathways [27], we also tested whether the “headless” phenotype was promoted by Ryk activity. However, and in contrast to β-catenin, the embryonic lethality of Apcmin/fl mice was not rescued by genetically limiting the expression of the atypical tyrosine kinase Ryk, because we failed to recover either Apcmin/fl;Ryk+/− or Apcmin/fl;Ryk-/- compound mutant mice at weaning (Table S1D), suggesting that Ryk expression was not contributing to the Wnt/β-catenin induced phenotype.

Collectively, our observations extend previous reports that identified a Wnt signaling gradient along the anterior-posterior axis and a requirement for Dkk1 and other Wnt antagonists at the anterior end to prevent posteriorization [3]–[6],[28],[29]. In particular, our experiments clarify genetically that the tight signaling requirements for head morphogenesis previously attributed to Apc or the extracellular components Dkk1 [3], Sfrp [4],[30], Wnt3a [9] and Wnt8a [5] occur exclusively through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Unlike Apcmin/fl embryos, Apcmin/min embryos die around the time of gastrulation [7], consistent with our observation that Apc580Δ/min MEFs, which serve as a model for unavailable Apcmin/min counterparts, reveal higher Tcf4 reporter activity than Apcmin/fl MEFs (see below). Since the morphological defects in E4.75 Apcmin/min embryos correlate with excessive nuclear β-catenin in the epiblast and primitive ectoderm [8], we also examined the effect of genetically limiting β-catenin in these embryos. Unlike the phenotypic rescue observed in Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice, we detected Apcmin/min;Ctnnb1+/− embryos only at E4.5 and E5.5 but not at later stages (E6 and E7). This finding is reminiscent of the time points of embryonic death of Apcmin/min embryos [7] and suggested that reduction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling was insufficient to rescue their death immediately after gastrulation (data not shown). Therefore, higher threshold levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling selectively inhibit development at an earlier stage (i.e. gastrulation) and genetic reduction of Wnt/β-catenin signaling through ablation of one Ctnnb1 allele reduces signaling only below the threshold that is tolerated during later stages of development. However, we cannot formally exclude other essential function(s) of the full-length Apc protein, which could be provided by residual full-length protein encoded by the Apcfl allele, and which may be required around the time of gastrulation.

Threshold levels in intestinal polyposis

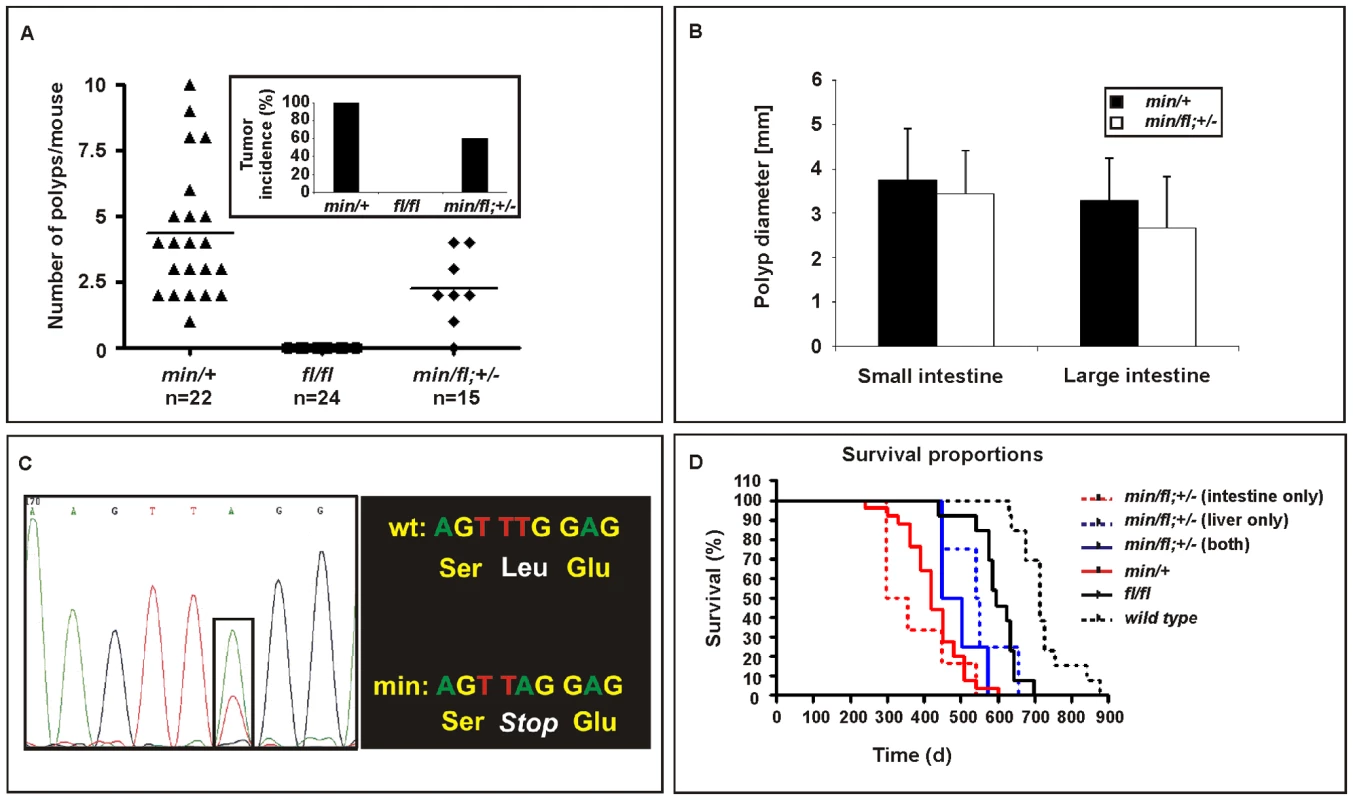

Apcmin/+ mice develop intestinal polyposis upon spontaneous LOH of the wild-type Apc allele which arises from centromeric somatic recombination [31],[32]. Meanwhile, genetic studies estimated the polyposis threshold level to correspond to 10–15% of the full-length protein produced from biallelic Apc expression [19]. We therefore established aging cohorts of mice harbouring different Apc allele combinations to constitute an allelic series for Wnt/β-catenin signaling based on the results in Figure 1. As observed previously, Apcfl/fl mice on a mixed 129Sv x C57BL/6 background remained free of intestinal polyps (>18 month, n = 24), while all Apcmin/+ mice (n = 22) developed macroscopic lesions primarily within the proximal portion of the small intestine. Although tumor multiplicity and incidence was reduced in Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice, leaving 6 of 15 mice (40%) free of polyps (Figure 3A), the remaining macroscopic lesions were of tubulo-villous structure and of similar size to those observed in age-matched Apcmin mice (Figure 3B). The similar latency of disease onset between Apcmin/+ and Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice suggests a common requirement for LOH. We therefore amplified exon 14 from polyps which contain the min allele-specific A>T transition to confirm LOH in all polyps from Apcmin (n = 12) and Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice (n = 4) (Figure 3C and data not shown). Based on our in vitro analysis (Figure 1), these results are similar to observations by Oshima et al. showing a requirement of less than 30% of wild-type Apc to prevent Wnt signaling from reaching the permissive threshold for intestinal polyps to form [33]. Surprisingly, restricting the pool of available cellular β-catenin in Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice selectively reduced tumor multiplicity rather than tumor size when compared to Apcmin mice. This suggests that, once LOH has occurred, Wnt/β-catenin signaling exceeds the permissive threshold level, even in light of a 50% reduction in β-catenin and fuels maximal tumor growth, which indeed may be mediated most effectively by submaximal Wnt activity [34].

Fig. 3. Intestinal tumor burden and impaired survival in Apc compound mutant mice.

(A) Multiplicity of large (>2mm) tumors in individual moribund mice of the indicated genotypes. Insert shows overall tumor incidence in cohorts of mice of the indicated genotypes. (B) Multiplicity of large (>2 mm) tumors in the small and large intestine of individual moribund (min/+) and compound (min/fl; +/−) mice. (C) Representative allele-specific nucleotide sequence of DNA extracted from an intestinal tumor of a (min/fl; +/−) mouse. Samples were scored as having lost the wild-type allele when the ratio between the peak intensities (boxed area) was ≤0.6 [52]. (D) Survival curve of mice of the indicated genotypes. Livers and the intestines of (min/fl; +/−) mice were analyzed for macroscopic evidence of tumors before being allocated to cohorts with lesions confined to the indicated organ only. Genotypes are as follows: wild-type (+/+); Apcmin/+ (min/+); Apcfl/fl (fl/fl); Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (min/fl; +/−). All mice were on a mixed genetic 129Sv x C57BL/6 background. Threshold levels of hepatocellular carcinogenesis

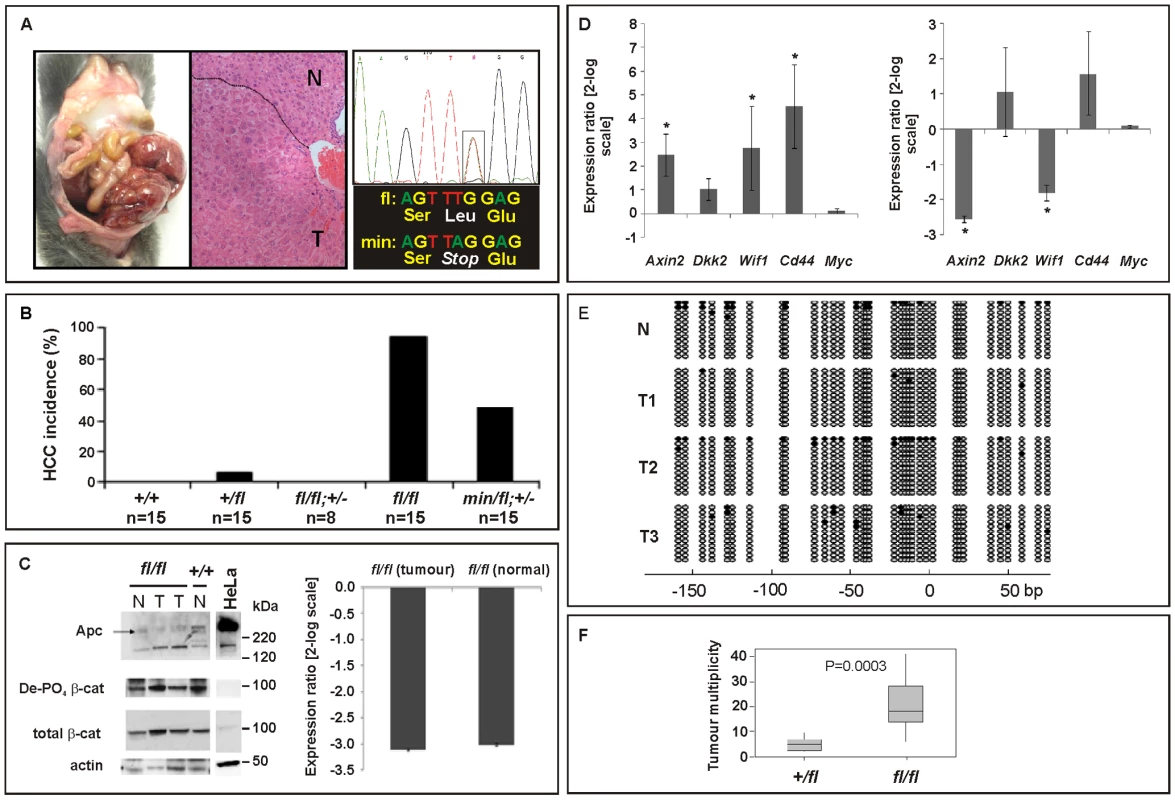

In humans, de-regulated WNT/β-catenin signaling plays an important role during onset and progression of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) and frequently arises from either dominant mutations in the CTNNB1 (β-catenin) gene, or biallelic inactivation of the AXIN1 and AXIN2 genes that involves LOH associated with somatic (epi-)mutation [35]–[37]. Somatic APC mutations, by contrast, are rarely associated with liver carcinogenesis, but FAP patients with germline APC mutations frequently develop hepatoblastomas as well as colonic adenocarcinomas [38]. In addition, adenovirally transduced, complete Apc gene inactivation in the murine liver resulted in hepatomegaly-associated mortality [39], while its sporadic inactivation triggered the development of HCC [40]. We therefore assessed the incidence of liver tumors in moribund mice of the different Apc allele combinations. We found that all Apcfl/fl mice (n = 15), but none of their Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/− littermates (n = 8), had developed HCC by 450 days of age (Figure 4A and 4B), but remained free of intestinal polyps (Figure 3A). We also used PCR analysis to exclude Cre-independent, spontaneous recombination of the Apcfl allele(s) in these tumors (Figure S2). Taken together with our observation of a reduced (but not complete loss) of Apc protein, this argues that tumors are formed with low level Apc and not in the absence of Apc. Therefore, our results suggest not only that HCC formation can occur due to excessive Wnt/β-catenin signaling but importantly that the permissive signaling threshold for hepatic tumorigenesis is lower than that for intestinal tumorigenesis consistently associated with LOH. Surprisingly, we observed HCC in 47% of Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice (n = 15) including 20% that showed intestinal co-morbidity. Survival analysis of mice from this cohort, where disease was confined either to the intestine (n = 6) or the liver (n = 4; Figure 3D), suggested the requirement for a stochastic secondary event to occur akin to intestinal Apc LOH. However, our genomic analysis of hepatic biopsies from Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice confirmed the absence of Apc LOH (Figure 4A), while qPCR and Western blot analysis revealed similar Apc expression between hepatic lesions and adjacent unaffected tissue from Apcfl/fl mice (Figure 4C). As expected, expression of Wnt target genes in unaffected livers from Apcfl/fl mice was elevated compared to livers from wt mice (Figure 4D). Meanwhile, in Apcfl/fl mice we found further, tumor-specific overexpression of some Wnt-target genes (incl. Cd44) that coincided with attenuation of others (notably encoding the negative regulators Axin2, Dkk2 and Wif1).

Fig. 4. Liver phenotype in Apc mutant mice.

(A) Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) of moribund Apcfl/fl and representative haematoxilin-eosin stained cross section with the dotted line indicating the boundary between normal (N) and tumoral (T) tissue. Representative allele-specific nucleotide sequence of DNA extracted from a liver tumor of a (min/fl; +/−) mouse demonstrating allelic balance between of the Apcmin and the floxed wt allele (boxed area). (B) Incidence of HCC in mice of the indicated genotypes. (C) Western blot and qPCR analysis of full-length Apc protein and Apc mRNA in normal (N) and tumoral (T) liver tissue of Apcfl/fl and Apc+/+ mice. Cell lysates of HeLa cells transfected with a plasmid encoding full-length wild-type Apc serves as an antibody specificity control. The abundance of de-phosphorylated, active (De-PO4) and total β-catenin protein in the same tissue extracts are shown with β-actin serving as a loading control. kDa, protein size marker in kilo Daltons. (D) Comparative qPCR analysis of representative Wnt target gene expression between normal and tumoral liver tissue collected from moribund Apcfl/fl mice (right panel). A comparable analysis was also performed on liver tissue from healthy 5mo old Apcfl/fl and wild-type mice (left panel). Mean ± SD with n≥3 mice per group. * P<0.05. (E) Bisulfite sequencing of the CpG island within the Axin2 promoter from adjacent normal (N) and tumor liver tissue (T1, T2, T3) from Apcfl/fl mice. Each vertical line refers to a CpG dinucleotide at the indicated position relative to the transcriptional start site. Following bisulfite-treatment, DNA was subcloned and sequenced. Horizontal lines represent individual sequences with open and full circles denoting unmethylated and methylated CpG residues, respectively. (F) Boxplot diagram comparing liver tumor multiplicity in +/fl mice (n = 9) and fl/fl mice (n = 12) 6 to 8 months after treatment with DEN. p = 0.0003 (Mann-Whitney). Genotypes are as follows: wild-type (+/+); Apc+/fl (+/fl); Apcfl/fl (fl/fl); Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (fl/fl; +/−); Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (min/fl; +/−). All mice were on a mixed 129Sv x C57BL/6 background. In order to clarify the nature of potential additional somatic mutations that may affect or cooperate with Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we excluded the presence of activating mutations in Ctnnb1-exon3 that would ablate the negative regulatory phosphorylation sites in β-catenin (Table S2A). We also failed to identify aberrant hypermethylation of the proximal Axin2 promoter (Figure 4E) and also excluded activating mutations in codons 12, 13 or 61 of H-Ras (Table S2B), although Harada et al. previously observed that simultaneous introduction of H-Ras and a constitutively active form of β-catenin by adenoviral gene transfer conferred HCC, while introduction of β-catenin alone did not [41],[42]. Indeed, exposure of Apcfl/fl mice to the liver-specific carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN), which is known to promote mutations in H-Ras, resulted in a higher tumor incidence than in Apc+/fl mice (Figure 4F). Contrary to the observation with intestinal lesions collected from Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− and Apcmin mice, we found that hepatic tumor volumes in Apcfl/fl mice were larger than in Apc+/fl mice (261 mm3±167 mm3 (n = 12) vs. 193 mm3±414 mm3 (n = 9), p = 0.036; Mann-Whitney test; mean ± SEM; n = 9) suggesting that the extent of aberrant Wnt/β-catenin activity may control both initiation and progression of lesions in the liver.

Collectively, these data suggest differential signaling threshold requirements for intestinal and hepatic tumorigenesis and likely differences in the molecular mechanisms by which Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes tumorigenesis in these two tissues. The relatively low proliferative activity of the hepatic stem cell compartment, for instance, may provide protection from Apc LOH, even when facilitated by haploinsufficient expression of a recQ-like DNA helicase in Apcmin/+;BlmCin/+ compound mutant mice which remain free of HCC [43]. In light of the lack of Axin2 promoter hypermethylation, the reduction of tumor-specific Axin2 expression may arise from other stochastic events. For instance, the AXIN2 locus contributes to some cancers by LOH or rearrangements in humans [44]. On the other hand, chronic inflammation and the associated excessive activation of the Interleukin-6 pathway may cooperate with activating mutations in CTNNB1 during malignant transformation of human HCC [45]. Despite similar Tcf4 reporter activity recorded between Apcfl/fl and Apcmin MEFs, Apcmin mice remained free of HCC. This observation may be explained by the premature death of Apcmin relative to Apcfl/fl mice (Figure 3D) together with the late onset of liver tumorigenesis. Indeed, we observe hepatic tumors in the Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice which live longer than Apcmin mice. On the other hand, hepatic tissue shows exquisite sensitivity to differential threshold levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, whereby the resulting signaling gradient provides a mechanism for metabolic liver zonation [39]. Indeed, we observed here that partial attenuation of full-length Apc expression in Apcfl/fl mice not only increased the number of cells with nuclear β-catenin (Figure 5A and 5B), but also altered expression of Wnt target genes and liver zonation. In particular, and in agreement with our previous findings [46], we observed that attenuation of full-length Apc favored expansion of a perivenous gene expression program (incl. GS, Glt1 and RHBG) at the expense of a periportal signature (incl. CPS, Arg1 and Glut2) (Figure 5A and 5C). Our observation that aberrant Wnt signaling in Apcfl/fl mice in the absence of additional somatic mutations in H-Ras bias towards tumors with perivenous characteristics is consistent with the finding that H-Ras mutated HCCs favor a periportal gene expression program [47].

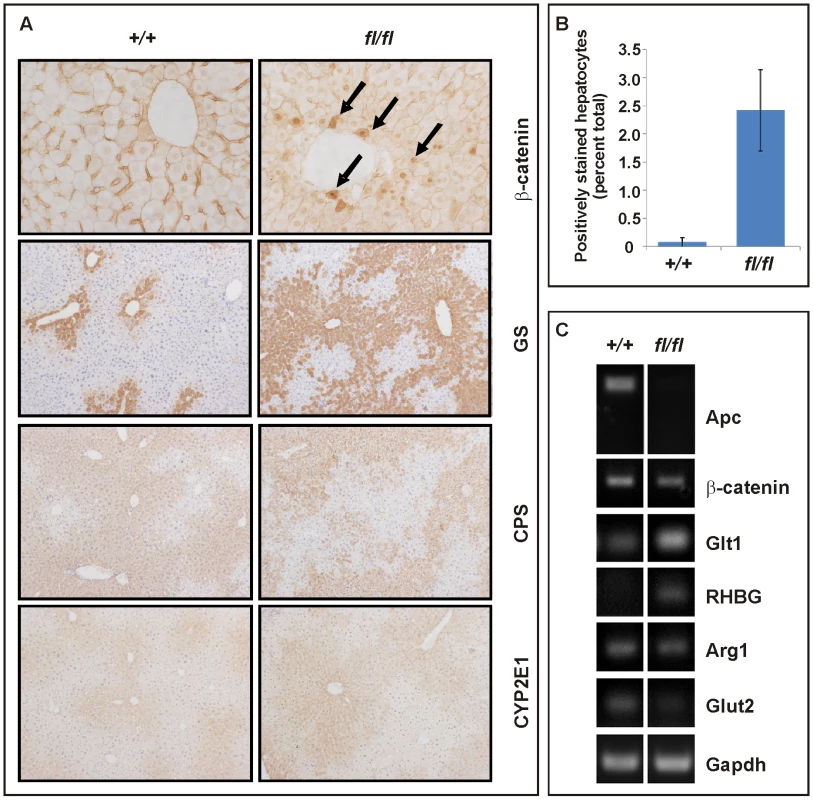

Fig. 5. Liver zonation is affected in hypomorphic Apcfl/fl mutant mice.

(A) Immunohistochemical expression analysis for β-catenin, glutamine synthetase (GS), carbamoylphosphate synthetase (CPS) and Cyp2E1 was performed on livers of age-matched wild-type (+/+) and (fl/fl) mice. Arrows point to nuclear β-catenin staining. (B) Hepatocytes with nuclear β-catenin staining were expressed as a percentage of total hepatocytes scored in age-matched wild-type (+/+; n = 3) and (fl/fl; n = 4) mice. p = 0.025 (Mann-Whitney). (C) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis from liver of 5mo old healthy (+/+) and (fl/fl) mice for assessment of expression of Apc, CtnnB1, along with the perivenous markers Glt1 (encoding a transporter of glutamate), RHBG (encoding the ammonium transporter), and the periportal markers Arg1 (encoding arginase1) and Glut2 (encoding glutaminase 2). Gapdh serves a as an RT-PCR amplification control. Reconciling tissue-specific phenotypes against different levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling

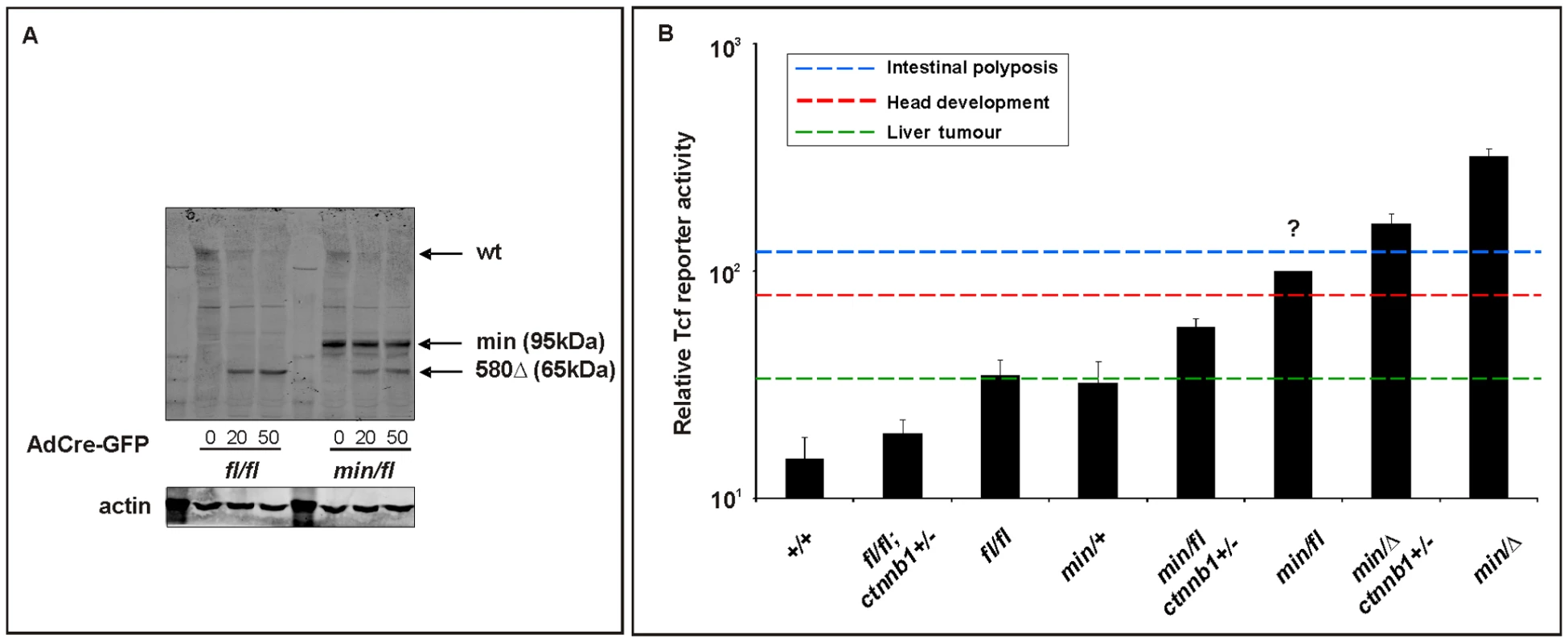

To gain biochemical insights into the extent to which Wnt signaling thresholds are related to the tumorigenic response in mice, we generated MEFs of genotypes similar to those of cells having undergone Apc LOH in Apcmin mice. In particular, we inactivated the latent Apcfl allele by Cre-mediated recombination in MEFs following infection with an AdCre-GFP adenovirus that expressed the Cre-recombinase as a GFP-fusion protein (Figure S3). Western blot analysis confirmed expression of the 580 amino acid truncated protein encoded by the recombined Apc580Δ allele, in the presence of the 850 amino acid Apcmin protein (Figure 6A). To prevent our analysis from being affected by potential “plateau effects”, we stimulated MEFs with submaximal concentrations of Wnt3a and found a ∼3-fold increase in Tcf-reporter activity between cells harboring the unrecombined Apcfl or recombined Apc580Δ allele, respectively (Figure 6B, compare Apcmin Δ vs. Apcmin/fl and Apc min/Δ;Ctnnb1+/− vs. Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/−). Furthermore, we confirmed that ablation of one Ctnnb1 allele reduced reporter activity by approximately 50% (compare Apcmin/Δ vs. Apcmin/Δ;Ctnnb1+/−; Apcmin/fl vs. Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− and Apc fl/fl vs. Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/−), and the comparison suggested similar Tcf4-reponsivenes between Apcmin/+ and Apcfl/fl cells. As predicted from the extent of the activating Apc mutations, we also observed a gradual increase of Tcf reporter activity in the absence of Wnt3a ligand (Figure S4).

Fig. 6. In vitro assessment of Wnt signaling in MEFs from Apc hypomorphic mice.

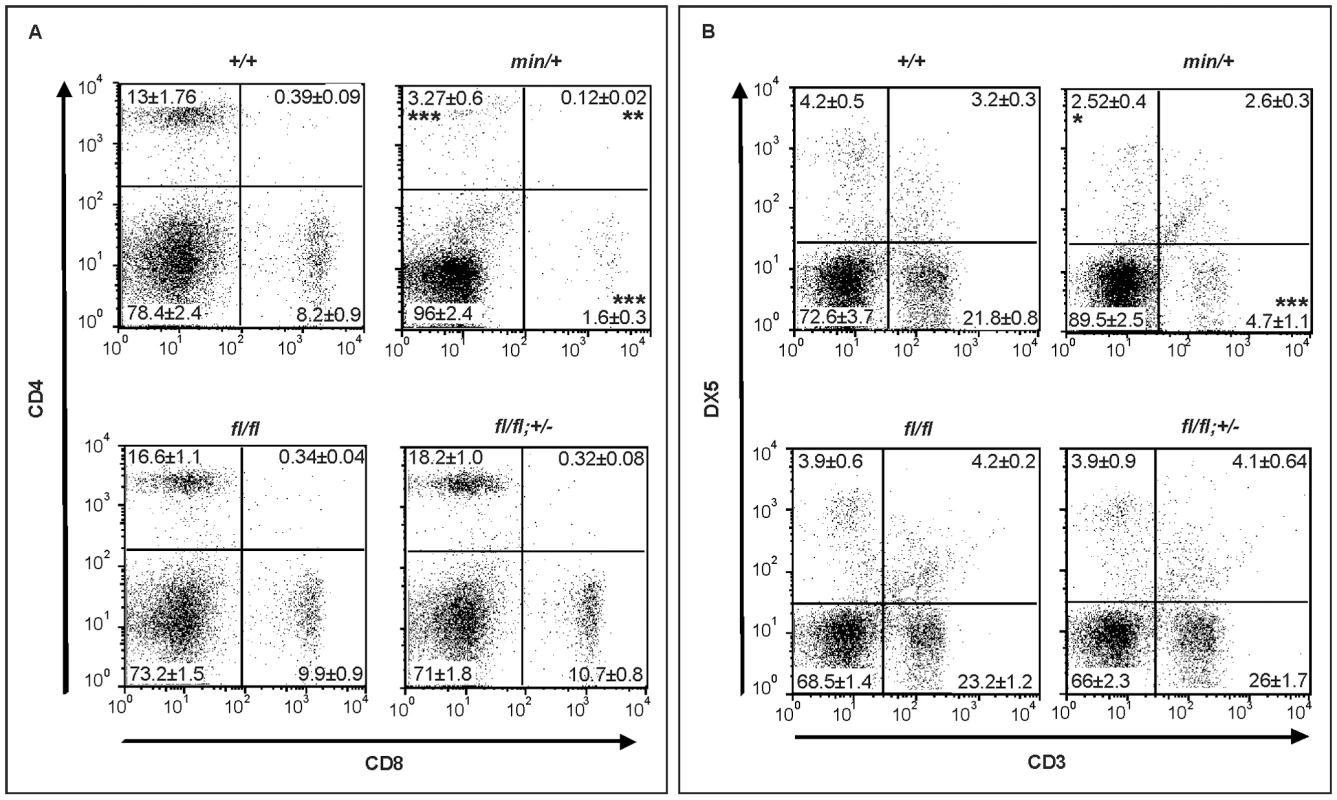

(A) Western blot analysis of MEF cell lysates, prepared from (fl/fl) and (min/fl) mice, 48 h after infection with Cre-GFP expressing adenovirus (AdCre-GFP) at different concentrations. Note the gradual reduction of full-length Apc protein (wt) with increasing amount of AdCre-GFP administration and simultaneous accumulation of the truncated Apc580Δ protein encoded by the recombined Apcfl allele. The truncated Apc protein encoded by the Apcmin allele is indicated (min). (B) Tcf4 reporter activity in MEFs of the indicated genotype in response to a submaximally active concentration of Wnt3a-conditioned medium. Activity was assessed following transient transfection with pSuperTopFlash. Cells were harvested 48 h later and assayed for luciferase activity using the dual luciferase system. The activity of the Tcf4 reporter in (min/fl) MEF exposed to a submaximal Wnt3a stimulation was arbitrarily set to 100 and analysis was performed in triplicate cultures. Horizontal lines indicate the signaling threshold predicted for the indicated phenotypes to occur in mice of the corresponding genotypes. The question mark refers to the position of the “intestinal threshold” line relative to reporter activity in min/fl MEFs, since the corresponding adult min/fl mice can not be generated. At least two independent experiments were performed in triplicates for each genotype. Mean ± SD. Note: Histograms refer to situation before LOH, intestinal polyposis threshold to situation after LOH, where applicable. Genotypes are as follows: wild-type (+/+); Apcmin/+ (min/+); Apcfl/fl (fl/fl); Apcmin/fl (min/fl); Apcmin/Δ580 (min/Δ); Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (fl/fl;ctnnb1+/−); Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (min/fl;ctnnb1+/−); Apcmin/Δ580;Ctnnb1+/− (min/Δ;ctnnb1+/−). All MEFs were derived from mice on a mixed genetic 129Sv x C57BL/6 background. Since systemic effects observed in adult Apcmin/+ mice may arise secondary to LOH-dependent intestinal tumorigenesis, we next used Apcfl/fl mice to explore this in the context of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling requirement for the maintenance of the hematopoietic cell population [48]. Specifically, Apcmin/+ mice develop lymphodepletion around the time when intestinal tumors are observed [49], and this is associated with a progressive loss of immature and mature thymocytes, and the depletion of splenic natural killer (NK) cells. Comparison of 17 week old wild-type, Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/−, Apcfl/fl and Apcmin/+ mice revealed a strong reduction of mature single positive CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the spleen of Apcmin mice and a less pronounced reduction in immature double positive CD4+,CD8+ cells (Figure 7A and Figure S5A). Moreover, this was reflected by a reduction in splenic CD3+ thymocytes and DX5+, CD3- NK-cells (Figure 7B and Figure S5B) in Apcmin/+ mice when compared to Apcfl/fl mice. Since we did not observe lymphodepletion as a consequence of incremental increases in Wnt/β-catenin signaling from wild-type to Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/− and Apcfl/fl mice (where the latter allele combination generates comparable signaling to that of Apcmin/+ cells), we conclude that this phenotype in aging Apcmin/+ mice is likely to be secondary to LOH-induced intestinal tumorigenesis. This conclusion is consistent with the lymphodepletion phenotype persisting in tumor-bearing irradiated Apcmin/+ mice that have been reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow [49] and our observation that thymic atrophy and associated T-cell depletion reported by Coletta et al., [49] in their tumor bearing 14 week old Apcmin/+ mice is not a reproducible finding at 17 weeks in our Apcmin/+ colony (data not shown) which displays a relative delay in polyposis onset.

Fig. 7. Lymphodepletion in Apc hypomorphic mice.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+/CD8+ stained splenocytes from 17 week old mice of the indicated genotypes. Representative results from one individual mouse are shown with the percentages contribution to each quadrant shown as Mean ± SD from at least 3 mice. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of CD3+/DX5+ stained splenocytes from 17 week old mice of the indicated genotypes. The NK cell population (DX5+;CD3−) are within the top left gate, and the bottom gates contain CD3+ T cells. Representative results from one individual mouse are shown with the percentages contribution to each quadrant shown as Mean ± SD from at least 3 mice. Genotypes are as follows: wild-type (+/+); Apcmin/+ (min/+); Apcfl/fl (fl/fl); Apcfl/fl;Ctnnb1+/− (fl/fl; +/−). All mice were on a mixed genetic 129Sv x C57BL/6 background. The present study underscores the power of hypomorphic alleles in the mouse to understand mechanisms that help to explain at the molecular level the specificity of pleiotropic signaling cascades. Here, we propose the existence of differential permissive Wnt/β-catenin signaling threshold levels during development and tissue homeostasis, and how they relate to each other with respect to specific pathophysiological outcomes. Combining biochemical assessment of different Apc allele combinations in MEFs with the corresponding mouse phenotype genetically defines threshold levels that are lower for liver tumorigenesis than for influencing cellular identity along the anterior-posterior axis, which in turn are lower than that required for intestinal tumorigenesis (Figure 6B). Our data complement those by Ishikawa et al [50] who observed a more severe head morphogenesis defect in mice homozygous for the hypomorphic ApcneoR allele which showed an 80% attenuation of full-length Apc protein (compared to ∼70% in Apcmin/fl cells, Figure 1A) and a 7-fold increase in Tcf4-reporter activity (compared to ∼5.5-fold in Apcmin/fl cells, Figure 1B and Figure 6B). Previously, we have shown that functional cooperation between individually insufficient (epi-) genetic alterations induced sufficient aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling to trigger intestinal tumorigenesis in compound A33Dnmt3a;Apcmin mice, with polyps characterized by retention of the wild-type Apc allele and epigenetic silencing of the Sfrp5 gene [51]. Together with the findings presented here, these observations add further support to the “just-right” signaling model which predicts cellular transformation to require specific and distinct dosages of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in intestinal, mammary or hepatic cells, and which was based on the observation that LOH in mice carrying the hypomorphic Apc1572T allele predisposed to metastatic mammary adenocarcinomas rather than intestinal or hepatic tumorigenesis [52]. Indeed, analysis of somatic mutations found in polyps of FAP patients indicates an active selection process favoring APC genotypes that provide residual levels of β-catenin regulation over its complete loss, which would trigger maximal activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [21]. Furthermore, our results demonstrate a lower requirement of Wnt/β-catenin activation levels for neoplastic transformation of hepatocytes than of intestinal epithelium. Meanwhile, human HCC are frequently associated with somatic mutations in AXIN1 or AXIN2 rather than with those in APC [36],[37] suggesting that APC truncation mutations may be selected against during the process of hepatocyte transformation. Our findings that the frequency of HCC is higher in Apcfl/fl mice than in Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice (despite the higher Tcf reporter activity in MEFs of the latter genotype) may not only be accounted for by the shorter overall survival of Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice, but also predicted from the “just-right” signaling model [21],.

Our data also implies that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is likely to conform to cell type-specific bistable switches, where the input stimulus must exceed a threshold to change from one cellular state (and associated response) to another. In the context of Apc LOH-dependent intestinal polyposis, for instance, the predicted two-fold increase of Wnt/β-catenin signaling between Apcmin/Δ;Ctnnb1+/− cells (corresponding to Apcmin/LOH;Ctnnb1+/− lesions in Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice) and Apcmin/Δ cells (corresponding to Apcmin/LOH lesions in Apcmin/+ mice, Figure 6B), has no further detrimental effect on polyposis-associated survival of Apcmin/+ compared to Apcmin/fl;Ctnnb1+/− mice (Figure 3D). Indeed, a recent report delineates a nested feedback-loop that may include a Wnt signaling-associated MAPK cascade [53] as one of the components which provides the non-linear input-output relationship for GSK3β and associated Wnt/β-catenin activity [54] to generate the dramatic threshold responses that characterize a bistable system.

Differential sensitivity to genetic dosage provides the basis for establishing therapeutic windows when targeting non-mutated components in diseased tissue. Indeed, for instance, the notion of therapeutic exploitation of non-oncogene addiction is based on the difference in signaling thresholds tolerated between normal and neoplastic cells. Based on our hitherto limited capacity to target and/or compartmentalize drug delivery, global single-allele inactivation models may provide a convenient first screen to identify potential drug targets. Here, we extend this concept from our previous findings for Stat3 in the context of inflammation-associated gastric cancer [55] to Ctnnb1 in tumors of the liver and intestine and associated aberrant Wnt signaling.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animals were handled in strict accordance with good animal practice as defined by the relevant national and/or local animal welfare bodies, and all animal work was approved by the appropriate committee.

Mice

Heterozygous Ctnnb1+/− mice were generated by excising exons 3–6 from the germline following the mating Ctnnb1fl/fl males with female C57Bl/6 E2a:Cre mice [56]. Ryk+/−, the Apc mutant Apcmin/+ and Apcfl/fl mice and the BAT-gal transgenic reporter mice have been described previously [22],[23],[57],[58]. All experimental mice were on a mixed genetic 129Sv x C57BL/6 background.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) expression analysis

qPCR analysis from liver was performed as described [59]. Following extraction of total RNA with TRIzol reagent (Sigma), first strand complementary DNA was synthesized using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen). The PCR reactions were carried out under the following conditions: 94°C for 2 min, denaturation at 92°C for 30 s, annealing at 56°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 45 s. Primers were obtained from Invitrogen. The number of cycles was 20 for GAPDH, 25 for Arginase1, Glut2 and RHGB, and 30 for β-catenin and Apc. The calculation of relative expression ratios was carried out with the Relative Expression Software Tool (REST) Multiple Condition Solver (MCS) (http://www.gene-quantification.com/) using the pairwise fixed reallocation randomization test. Primers used are listed in Table S3.

Tissue fixation, embedding, and processing

Dissected liver tissue was fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde or overnight in 10% formalin (Sigma) at 4°C depending on the antibody used (see below). After fixation, tissue samples were transferred to 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin wax.

Immunohistochemical analysis of adult

Samples were prepared as described previously [46]. Immunoperoxidase staining for GS, CPS I and CYP2E1 (4% PFA) and β-catenin (formalin) was carried out as follows. Sections were dewaxed in Histoclear for 7 min. Sections were washed in PBS and blocked for 30 min in 2% Roche blocking buffer (Roche) before addition of the following antibodies: anti-mouse GS (1∶400; BD Transduction Laboratories), anti rabbit CPS (1∶1,000; a kind gift of Wouter Lamers), and CYP2E1 (1∶500; a kind gift of Magnus Ingelman-Sundberg) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Immunostaining for β-catenin (1∶50; BD Transduction Laboratories) was carried out as previously described [60]. Excess primary antibody was removed by washing 3 times in PBS for 10 min each. Sections were incubated with the DAKO Envision peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse or rabbit secondary antibody polymer for 30 min. The DAB substrate–chromogen mixture was added to the sections and allowed to develop for 10 min. The reaction was terminated in dH2O and the sections counterstained with hematoxylin where appropriate. Specimens were observed using a Leica DMRB microscope. Image collection from the Leica was made with a Spot camera and images collated into figures in Photoshop.

Cell culture and transfections

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were derived from E13 embryos and propagated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The day before transfection, cells were seeded at 5×104 cells/well into 24-well plates. Wnt3a-conditioned medium was a gift from Liz Vincan (Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Melbourne) and Nicole Church (JPSL, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Melbourne) and the recombinant human Dkk1 - was from R&D Systems (#1090-Dk). Transfections were carried out using either FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche) or nucleofector (Amaxa), 200 ng pSuperTOPflash, 4 ng pRL-CMV and 200 ng of pCMV-HA-SFRP5 expression construct. Two days later, cultures were processed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega) and luminescence was measured using a Lumistar Galaxy luminometer (Dynatech Laboratories).

Induction of liver carcinogenesis

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of diethylnitrosamine (DEN) (10 mg/ml) at 40 mg/kg at 14 days of age. Mice were sacrificed 6–8 months later and livers were scored for the presence of macroscopic tumors.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions from spleens were prepared by passing organs through a 40 µm mesh. Cell suspensions were treated with NH4Cl to lyse red blood cells, and then nonspecific binding was blocked by incubating with mouse Fc block (2.4G2). The cells were incubated for 30 min at RT with the relevant fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to CD3 (clone 2C11), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7) and DX5 (#558295). All antibodies and Fc Block for flow cytometry were purchased from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA. Expression of surface markers on cells was detected using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.) Forward scatter/side scatter (FCS/SSC) gating was used to exclude debris and doublets and dead cells were gated out on the basis of PI positivity measured on the FL-3 channel.

LacZ staining for embryos

Embryos are killed by submerging in ice-cold PBS for a few minutes and fixed by rocking for 45 min in ice-cold 4% PFA in PBS. Specimens are washed 3×5 min in PBS and subsequently incubated o/n at 30°C in X-gal staining solution. After washing in PBS for a few minutes, stained embryos were photographed.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed using Triton-X based lysis buffer (30 mM Hepes), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X-100, 2 mM MgCl2), with Complete EDTA-free protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche). This was followed by centrifugation at 13000 g for 5 min at 4°C and denaturing at 95°C for 5 min. Protein concentration was determined using a BIO-RAD assay kit. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen), blotted onto nitrocellulose and incubated with the appropriate antibody overnight. After incubation with the secondary antibody, proteins were visualized using ECL chemiluminescence detection kit (GE Healthcare). For detection of APC, cell lysates were prepared by resuspending cells in ice-cold Lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100, 1% deoxycholate and Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail] and incubation on ice for 15 min. Lysates were clarified by microcentrifugation at 16,060 g for 30 min at 4°C. Total cell lysates were then analysed by SDS-PAGE (3–8% NuPAGE) and detected using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Odyssey). Quantification of Western blots was performed by using Image J pixel analysis (NIH Image software). Data from Western blots is presented as band density normalized to the loading control, and is representative of three independent experiments. Anti-Active-β-Catenin (anti-ABC), clone 8E7, was from Upstate (#05-665), rabbit polyclonal antibody to the N-terminus of APC (H-290) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz) and anti-mouse Actin (AC-40) was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Apc LOH determination, promoter methylation analysis

Parts of exon 16 containing the Min allele specific T>A substitution was PCR-amplified and the gel-purified amplicons were sequenced on an ABIprism377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Apc (ex16) forward primer 5′-TCACCGGAGTAAGCAGAGACAC-3′, reverse primer 5′-TTTGGCATAAGGCATAGAGCAT-3′. Bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA and methylation specific PCR was carried out as described [61].

Production of adenoviruses and adenoviral infection

Adenovirus expressing Cre Recombinase fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP; Cre-GFP) was produced by cloning a cDNA encoding Cre-GFP into pShuttle, the adenoviral transfer vector (Q-BIOgene). Linearised plasmid was then co-transformed into Escherichia coli with pAdEasy1 (Ad5ΔE1/ΔE3) (Q-BIOgene). The pAdCreGFP was linearised and transfected into Q-HEK293A cells (Q-BIOgene) using the calcium phosphate method (Promega). 10 days after transfection, adenoviral infected cells were collected and the adenovirus was released by three rounds of freeze/thawing, and amplification in Q-HEK293A cells, as described in the protocol (Q-BIOgene). For Tcf4 reporter assays MEFs were plated at 5×104 cells/well and were transfected with pSuperTOPflash, and pRenilla-luc. After 24 h, cells were infected with either Ad-LacZ (control virus) or Ad-CreGFP (20 µl/well, TCID50 1.995×108/ml). 48 h after infection, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. For Western blot analysis, MEFs were plated at 1.5×105 cells/well in 6 well plates and infected with AdCreGFP (20 and 50 µl/well, TCID50 1.995×108/ml) or Ad-LacZ for 48 h. For microscopy, MEFs were plated on glass coverslips, infected with virus, and after 48 h, infected cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 4% formaldehyde/PBS for 5 min. DIC and fluorescent images were produced using a Nikon 90i microscope.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test or, where indicated, using Mann-Whitney analysis.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KlausA

BirchmeierW

2008 Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8 387 398

2. CleversH

2006 Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127 469 480

3. MukhopadhyayM

ShtromS

Rodriguez-EstebanC

ChenL

TsukuiT

2001 Dickkopf1 is required for embryonic head induction and limb morphogenesis in the mouse. Dev Cell 1 423 434

4. SatohW

GotohT

TsunematsuY

AizawaS

ShimonoA

2006 Sfrp1 and Sfrp2 regulate anteroposterior axis elongation and somite segmentation during mouse embryogenesis. Development 133 989 999

5. PopperlH

SchmidtC

WilsonV

HumeCR

DoddJ

1997 Misexpression of Cwnt8C in the mouse induces an ectopic embryonic axis and causes a truncation of the anterior neuroectoderm. Development 124 2997 3005

6. HuelskenJ

VogelR

BrinkmannV

ErdmannB

BirchmeierC

2000 Requirement for beta-catenin in anterior-posterior axis formation in mice. J Cell Biol 148 567 578

7. MoserAR

ShoemakerAR

ConnellyCS

ClipsonL

GouldKA

1995 Homozygosity for the Min allele of Apc results in disruption of mouse development prior to gastrulation. Dev Dyn 203 422 433

8. ChazaudC

RossantJ

2006 Disruption of early proximodistal patterning and AVE formation in Apc mutants. Development 133 3379 3387

9. LewisSL

KhooPL

De YoungRA

SteinerK

WilcockC

2008 Dkk1 and Wnt3 interact to control head morphogenesis in the mouse. Development 135 1791 1801

10. MiyakiM

KonishiM

Kikuchi-YanoshitaR

EnomotoM

IgariT

1994 Characteristics of somatic mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene in colorectal tumors. Cancer Res 54 3011 3020

11. MiyoshiY

AndoH

NagaseH

NishishoI

HoriiA

1992 Germ-line mutations of the APC gene in 53 familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 4452 4456

12. PowellSM

ZilzN

Beazer-BarclayY

BryanTM

HamiltonSR

1992 APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature 359 235 237

13. LammiL

ArteS

SomerM

JarvinenH

LahermoP

2004 Mutations in AXIN2 cause familial tooth agenesis and predispose to colorectal cancer. Am J Hum Genet 74 1043 1050

14. LiuW

DongX

MaiM

SeelanRS

TaniguchiK

2000 Mutations in AXIN2 cause colorectal cancer with defective mismatch repair by activating beta-catenin/TCF signalling. Nat Genet 26 146 147

15. PolakisP

2000 Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev 14 1837 1851

16. McCartneyBM

NathkeIS

2008 Cell regulation by the Apc protein Apc as master regulator of epithelia. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20 186 193

17. SmitsR

KielmanMF

BreukelC

ZurcherC

NeufeldK

1999 Apc1638T: a mouse model delineating critical domains of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein involved in tumorigenesis and development. Genes Dev 13 1309 1321

18. SansomOJ

MenielVS

MuncanV

PhesseTJ

WilkinsJA

2007 Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature 446 676 679

19. LiQ

IshikawaTO

OshimaM

TaketoMM

2005 The threshold level of adenomatous polyposis coli protein for mouse intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 65 8622 8627

20. KielmanMF

RindapaaM

GasparC

van PoppelN

BreukelC

2002 Apc modulates embryonic stem-cell differentiation by controlling the dosage of beta-catenin signaling. Nat Genet 32 594 605

21. AlbuquerqueC

BreukelC

van der LuijtR

FidalgoP

LageP

2002 The ‘just-right’ signaling model: APC somatic mutations are selected based on a specific level of activation of the beta-catenin signaling cascade. Hum Mol Genet 11 1549 1560

22. MoserAR

PitotHC

DoveWF

1990 A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science 247 322 324

23. ShibataH

ToyamaK

ShioyaH

ItoM

HirotaM

1997 Rapid colorectal adenoma formation initiated by conditional targeting of the Apc gene. Science 278 120 123

24. MunemitsuS

AlbertI

SouzaB

RubinfeldB

PolakisP

1995 Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 3046 3050

25. Kimura-YoshidaC

NakanoH

OkamuraD

NakaoK

YonemuraS

2005 Canonical Wnt signaling and its antagonist regulate anterior-posterior axis polarization by guiding cell migration in mouse visceral endoderm. Dev Cell 9 639 650

26. MatsuoI

SudaY

YoshidaM

UekiT

KimuraC

1997 Otx and Emx functions in patterning of the vertebrate rostral head. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 62 545 553

27. ZhongW

2008 Going nuclear is again a winning (Wnt) strategy. Dev Cell 15 635 636

28. GurleyKA

RinkJC

Sanchez AlvaradoA

2008 Beta-catenin defines head versus tail identity during planarian regeneration and homeostasis. Science 319 323 327

29. LewisSL

KhooPL

Andrea De YoungR

BildsoeH

WakamiyaM

2007 Genetic interaction of Gsc and Dkk1 in head morphogenesis of the mouse. Mech Dev 124 157 165

30. HoangBH

ThomasJT

Abdul-KarimFW

CorreiaKM

ConlonRA

1998 Expression pattern of two Frizzled-related genes, Frzb-1 and Sfrp-1, during mouse embryogenesis suggests a role for modulating action of Wnt family members. Dev Dyn 212 364 372

31. LuongoC

MoserAR

GledhillS

DoveWF

1994 Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res 54 5947 5952

32. ShoemakerAR

LuongoC

MoserAR

MartonLJ

DoveWF

1997 Somatic mutational mechanisms involved in intestinal tumor formation in Min mice. Cancer Res 57 1999 2006

33. OshimaM

OshimaH

KobayashiM

TsutsumiM

TaketoMM

1995 Evidence against dominant negative mechanisms of intestinal polyp formation by Apc gene mutations. Cancer Res 55 2719 2722

34. PollardP

DeheragodaM

SegditsasS

LewisA

RowanA

2009 The Apc 1322T mouse develops severe polyposis associated with submaximal nuclear beta-catenin expression. Gastroenterology 136 : 2204-2213 e2201-2213

35. de La CosteA

RomagnoloB

BilluartP

RenardCA

BuendiaMA

1998 Somatic mutations of the beta-catenin gene are frequent in mouse and human hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 8847 8851

36. SatohS

DaigoY

FurukawaY

KatoT

MiwaN

2000 AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat Genet 24 245 250

37. TaniguchiK

RobertsLR

AdercaIN

DongX

QianC

2002 Mutational spectrum of beta-catenin, AXIN1, and AXIN2 in hepatocellular carcinomas and hepatoblastomas. Oncogene 21 4863 4871

38. HirschmanBA

PollockBH

TomlinsonGE

2005 The spectrum of APC mutations in children with hepatoblastoma from familial adenomatous polyposis kindreds. J Pediatr 147 263 266

39. BenhamoucheS

DecaensT

GodardC

ChambreyR

RickmanDS

2006 Apc tumor suppressor gene is the “zonation-keeper” of mouse liver. Dev Cell 10 759 770

40. ColnotS

DecaensT

Niwa-KawakitaM

GodardC

HamardG

2004 Liver-targeted disruption of Apc in mice activates beta-catenin signaling and leads to hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 17216 17221

41. HaradaN

MiyoshiH

MuraiN

OshimaH

TamaiY

2002 Lack of tumorigenesis in the mouse liver after adenovirus-mediated expression of a dominant stable mutant of beta-catenin. Cancer Res 62 1971 1977

42. HaradaN

OshimaH

KatohM

TamaiY

OshimaM

2004 Hepatocarcinogenesis in mice with beta-catenin and Ha-ras gene mutations. Cancer Res 64 48 54

43. GossKH

RisingerMA

KordichJJ

SanzMM

StraughenJE

2002 Enhanced tumor formation in mice heterozygous for Blm mutation. Science 297 2051 2053

44. HughesTA

BradyHJ

2005 Expression of axin2 is regulated by the alternative 5′-untranslated regions of its mRNA. J Biol Chem 280 8581 8588

45. RebouissouS

AmessouM

CouchyG

PoussinK

ImbeaudS

2009 Frequent in-frame somatic deletions activate gp130 in inflammatory hepatocellular tumours. Nature 457 200 204

46. BurkeZD

ReedKR

PhesseTJ

SansomOJ

ClarkeAR

2009 Liver zonation occurs through a beta-catenin-dependent, c-Myc-independent mechanism. Gastroenterology 136 : 2316-2324 e2311-2313

47. BraeuningA

IttrichC

KohleC

BuchmannA

SchwarzM

2007 Zonal gene expression in mouse liver resembles expression patterns of Ha-ras and beta-catenin mutated hepatomas. Drug Metab Dispos 35 503 507

48. ReyaT

DuncanAW

AillesL

DomenJ

SchererDC

2003 A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 423 409 414

49. ColettaPL

MullerAM

JonesEA

MuhlB

HolwellS

2004 Lymphodepletion in the ApcMin/+ mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis. Blood 103 1050 1058

50. IshikawaTO

TamaiY

LiQ

OshimaM

TaketoMM

2003 Requirement for tumor suppressor Apc in the morphogenesis of anterior and ventral mouse embryo. Dev Biol 253 230 246

51. SamuelMS

SuzukiH

BuchertM

PutoczkiTL

TebbuttNC

2009 Elevated Dnmt3a Activity Promotes Polyposis in Apc(Min) Mice by Relaxing Extracellular Restraints on Wnt Signaling. Gastroenterology.

52. GasparC

FrankenP

MolenaarL

BreukelC

van der ValkM

2009 A targeted constitutive mutation in the APC tumor suppressor gene underlies mammary but not intestinal tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet 5 e1000547 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000547

53. IshitaniT

KishidaS

Hyodo-MiuraJ

UenoN

YasudaJ

2003 The TAK1-NLK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade functions in the Wnt-5a/Ca(2+) pathway to antagonize Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol 23 131 139

54. JustmanQA

SerberZ

FerrellJEJr

El-SamadH

ShokatKM

2009 Tuning the activation threshold of a kinase network by nested feedback loops. Science 324 509 512

55. JenkinsBJ

GrailD

NheuT

NajdovskaM

WangB

2005 Hyperactivation of Stat3 in gp130 mutant mice promotes gastric hyperproliferation and desensitizes TGF-beta signaling. Nat Med 11 845 852

56. HuelskenJ

VogelR

ErdmannB

CotsarelisG

BirchmeierW

2001 beta-Catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell 105 533 545

57. HalfordMM

ArmesJ

BuchertM

MeskenaiteV

GrailD

2000 Ryk-deficient mice exhibit craniofacial defects associated with perturbed Eph receptor crosstalk. Nat Genet 25 414 418

58. MarettoS

CordenonsiM

DupontS

BraghettaP

BroccoliV

2003 Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 3299 3304

59. BurkeZD

ShenCN

RalphsKL

ToshD

2006 Characterization of liver function in transdifferentiated hepatocytes. J Cell Physiol 206 147 159

60. SansomOJ

ReedKR

HayesAJ

IrelandH

BrinkmannH

2004 Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev 18 1385 1390

61. FrommerM

McDonaldLE

MillarDS

CollisCM

WattF

1992 A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 1827 1831

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70Článek Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse ModelČlánek Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 1- Souvislost haplotypu M2 genu pro annexin A5 s opakovanými reprodukčními ztrátami

- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Příjem alkoholu a menstruační cyklus

- Hysteroskopická resekce děložního septa zlepšuje šanci na graviditu žen s jinak nevysvětlenou infertilitou

- Transfer zmraženého embrya zlepšuje výsledky IVF

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Irradiation-Induced Genome Fragmentation Triggers Transposition of a Single Resident Insertion Sequence

- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- Modeling of Environmental Effects in Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies and as Novel Loci Influencing Serum Cholesterol Levels

- Inverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons

- Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70

- Postnatal Survival of Mice with Maternal Duplication of Distal Chromosome 7 Induced by a / Imprinting Control Region Lacking Insulator Function

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse Model

- Understanding Gene Sequence Variation in the Context of Transcription Regulation in Yeast

- miR-30 Regulates Mitochondrial Fission through Targeting p53 and the Dynamin-Related Protein-1 Pathway

- Elevated Levels of the Polo Kinase Cdc5 Override the Mec1/ATR Checkpoint in Budding Yeast by Acting at Different Steps of the Signaling Pathway

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

- Co-Orientation of Replication and Transcription Preserves Genome Integrity

- A Comprehensive Map of Insulator Elements for the Genome

- Environmental and Genetic Determinants of Colony Morphology in Yeast

- U87MG Decoded: The Genomic Sequence of a Cytogenetically Aberrant Human Cancer Cell Line

- The MCM-Binding Protein ETG1 Aids Sister Chromatid Cohesion Required for Postreplicative Homologous Recombination Repair

- Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

- Differential Localization and Independent Acquisition of the H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 Chromatin Modifications in the Adult Germ Line

- Genetic Crossovers Are Predicted Accurately by the Computed Human Recombination Map

- Collaborative Action of Brca1 and CtIP in Elimination of Covalent Modifications from Double-Strand Breaks to Facilitate Subsequent Break Repair

- Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Novel Susceptibility Gene for Osteoporosis

- and Regulate Reproductive Habit in Rice

- Nonsense-Mediated Decay Enables Intron Gain in

- Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology

- The Systemic Imprint of Growth and Its Uses in Ecological (Meta)Genomics

- The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon

- Genotype and Gene Expression Associations with Immune Function in

- The Elongator Complex Regulates Neuronal α-tubulin Acetylation

- Rising from the Ashes: DNA Repair in

- Mis-Spliced Transcripts of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α6 Are Associated with Field Evolved Spinosad Resistance in (L.)

- BRIT1/MCPH1 Is Essential for Mitotic and Meiotic Recombination DNA Repair and Maintaining Genomic Stability in Mice

- Non-Coding Changes Cause Sex-Specific Wing Size Differences between Closely Related Species of

- Evidence for Pervasive Adaptive Protein Evolution in Wild Mice

- Evolutionary Mirages: Selection on Binding Site Composition Creates the Illusion of Conserved Grammars in Enhancers

- VEZF1 Elements Mediate Protection from DNA Methylation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání