-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Selective Pressures to Maintain Attachment Site Specificity of Integrative and Conjugative Elements

Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) are widespread mobile genetic elements that are usually found integrated in bacterial chromosomes. They are important agents of evolution and contribute to the acquisition of new traits, including antibiotic resistances. ICEs can excise from the chromosome and transfer to recipients by conjugation. Many ICEs are site-specific in that they integrate preferentially into a primary attachment site in the bacterial genome. Site-specific ICEs can also integrate into secondary locations, particularly if the primary site is absent. However, little is known about the consequences of integration of ICEs into alternative attachment sites or what drives the apparent maintenance and prevalence of the many ICEs that use a single attachment site. Using ICEBs1, a site-specific ICE from Bacillus subtilis that integrates into a tRNA gene, we found that integration into secondary sites was detrimental to both ICEBs1 and the host cell. Excision of ICEBs1 from secondary sites was impaired either partially or completely, limiting the spread of ICEBs1. Furthermore, induction of ICEBs1 gene expression caused a substantial drop in proliferation and cell viability within three hours. This drop was dependent on rolling circle replication of ICEBs1 that was unable to excise from the chromosome. Together, these detrimental effects provide selective pressure against the survival and dissemination of ICEs that have integrated into alternative sites and may explain the maintenance of site-specific integration for many ICEs.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003623

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003623Summary

Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) are widespread mobile genetic elements that are usually found integrated in bacterial chromosomes. They are important agents of evolution and contribute to the acquisition of new traits, including antibiotic resistances. ICEs can excise from the chromosome and transfer to recipients by conjugation. Many ICEs are site-specific in that they integrate preferentially into a primary attachment site in the bacterial genome. Site-specific ICEs can also integrate into secondary locations, particularly if the primary site is absent. However, little is known about the consequences of integration of ICEs into alternative attachment sites or what drives the apparent maintenance and prevalence of the many ICEs that use a single attachment site. Using ICEBs1, a site-specific ICE from Bacillus subtilis that integrates into a tRNA gene, we found that integration into secondary sites was detrimental to both ICEBs1 and the host cell. Excision of ICEBs1 from secondary sites was impaired either partially or completely, limiting the spread of ICEBs1. Furthermore, induction of ICEBs1 gene expression caused a substantial drop in proliferation and cell viability within three hours. This drop was dependent on rolling circle replication of ICEBs1 that was unable to excise from the chromosome. Together, these detrimental effects provide selective pressure against the survival and dissemination of ICEs that have integrated into alternative sites and may explain the maintenance of site-specific integration for many ICEs.

Introduction

Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs, also known as conjugative transposons) are mobile genetic elements that encode conjugation machinery that mediates their transfer from cell to cell. Most characterized ICEs were identified because they carry additional genes that confer phenotypes to the host cell. These can be genes involved in pathogenesis, symbiosis, and antibiotic resistances, among others {reviewed in [1]}. ICEs are typically found integrated in the host bacterial chromosome and can excise to form a circular product that is the substrate for conjugation. Their ability to spread to other organisms through conjugation makes ICEs important agents of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria, and they appear to be more prevalent than plasmids [2]. ICEs can also facilitate transfer (mobilization) of other genetic elements [1], [3], [4].

Some ICEs have a specific integration (attachment or insertion) site in the host genome whereas others are more promiscuous and can integrate into many locations. For example, SXT, an ICE in Vibrio cholera has one primary site of integration in the 5′ end of prfC [5]. In contrast, Tn916 has a preference for AT-rich DNA in many different hosts and integrates into many different chromosomal sites [6], [7]. Each strategy for integration has its benefits. The more promiscuous elements can acquire a wider range of genes adjacent to the integration sites, and their spread is not limited to organisms with a specific attachment site. On the other hand, site-specific elements are much less likely to disrupt important genes. The attachment site for these elements is typically in a conserved gene, often a tRNA gene [8], [9]. If sequences at the end of the integrating element are identical with the 3′ end of the gene (which is often the case), then gene function is not disrupted. Integration into conserved genes makes it likely that many organisms will have a safe place for these elements to integrate. We wished to learn more about the ability of site-specific ICEs to integrate into secondary integration (or attachment) sites, particularly if the primary site is not present in a genome. We wondered if an ICE could function normally in a secondary site and if there was any effect on the host.

We used ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis to analyze effects of integration into secondary attachment sites. ICEBs1 is a site-specific conjugative transposon that is normally found integrated into a tRNA gene (trnS-leu2) [10], [11]. ICEBs1 is approximately 20 kb (Figure 1), and many of its genes are similar to genes in other ICEs, including those in Tn916 [11], [12], the first conjugative transposon identified [13], [14]. It is not known what properties or advantages ICEBs1 confers on host cells, and naturally occurring ICEBs1 is not known to carry genes involved in antibiotic resistances, virulence, or metabolism. However, because of the conservation of many of its functions, the ease of manipulating B. subtilis, and the high efficiency of experimental induction of gene expression, ICEBs1 is extremely useful for studying basic and conserved properties of ICEs.

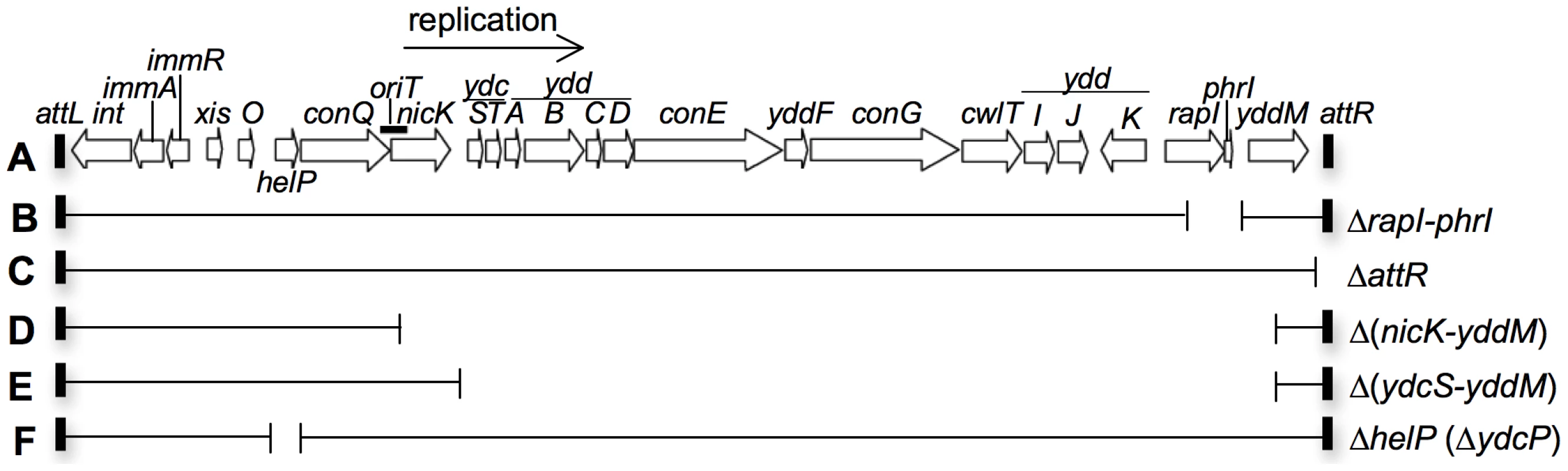

Fig. 1. Map of ICEBs1 and its derivatives.

A. The linear genetic map of ICEBs1 integrated in the chromosome. Open arrows indicate open reading frames and the direction of transcription. Gene names are indicated above or below the arrows. The origin of transfer (oriT) is indicated by a thick black line overlapping the 3′ end of conQ and the 5′ end of nicK. oriT functions as both the ICEBs1 origin of transfer and origin of replication [15], [23]. The thin black arrow indicates the direction of ICEBs1 rolling-circle replication. The small rectangles at the ends of ICEBs1 represent the 60 bp direct repeats that contain the site-specific recombination sites in the left and right attachment sites, attL and attR, that are required for excision of the element from the chromosome. B–F. Various deletions of ICEBs1 were used in this study. Thin horizontal lines represent regions of ICEBs1 that are present and gaps represent regions that are deleted. Antibiotic resistance cassettes that are inserted are not shown for simplicity. B. rapI and phrI are deleted and a kanamycin resistance cassette inserted. C. The right attachment site (attR) is deleted and a tetracycline resistance cassette inserted. D. The genes from the 5′ end of nicK and into yddM are deleted and a chloramphenicol resistance cassette inserted. E. The genes from the 5′ end of ydcS and into yddM are deleted and a chloramphenicol resistance cassette inserted. F. The entire coding sequence of helP (previously known as ydcP) and 35 bp in the helP-ydcQ intergenic region is removed. There is no antibiotic resistance cassette in this construct. Induction of ICEBs1 gene expression leads to excision from the chromosome in >90% of the cells, autonomous rolling-circle replication of ICEBs1, and mating in the presence of appropriate recipients [10], [11], [15]. After excision from the chromosome, autonomous replication of ICEBs1 is needed for its stability during cell growth and division [15]. In addition, excision is not needed for replication; ICEBs1 that is unable to excise from the chromosome undergoes autonomous unidirectional replication following induction of ICEBs1 gene expression [15]. At least some other ICEs appear to undergo autonomous replication [1], [16]–[18]. In addition, the genes in ICEBs1 that are required for autonomous replication are conserved [19]. Based on these observations and the properties of ICEBs1, we suspect that many ICEs undergo rolling circle replication and use the origin of transfer as an origin of replication and the cognate conjugative relaxase as a replicative relaxase [3], [19].

Our aim was to examine the physiological consequences of integration of ICEBs1 into secondary attachment sites. Previous work showed that in the absence of its primary attachment site (attB in the gene for tRNA-leu2), ICEBs1 integrates into secondary attachment sites [10]. Seven different sites were identified and characterized previously, providing insight into the chromosomal sequences needed for integration [10]. Work presented here extends these findings by identifying additional secondary sites, evaluating the ability of ICEBs1 to excise from these sites, and determining the effects of integration at these sites on host cells. Our results indicate that integration of ICEBs1 in secondary integration sites is deleterious to ICEBs1 and to the host cell. Excision and spread of ICEBs1 from the secondary sites was reduced or eliminated and there was a drop in cell viability due to autonomous replication of ICEBs1 that was defective in excision. These effects likely provide strong selective pressure for insertions into sites from which ICEBs1 can excise and against the propagation of insertions in secondary sites.

Results

Identification of secondary sites of integration of ICEBs1

We identified 27 independent insertions of ICEBs1 into secondary integration sites in the B. subtilis chromosome. Briefly, these insertions were identified by: 1) mating ICEBs1 into a recipient strain deleted for the primary attachment site attB (located in the tRNA gene trnS-leu2), 2) isolating independent transconjugants, and 3) determining the site of insertion in each of 27 independent isolates. The frequency of stable acquisition of ICEBs1 by strains missing attB was reduced to ∼0.5–5% of that of strains containing attB {Materials and Methods, and [Materials and Methods, and 10]}.

There were 15 different secondary integration sites for ICEBs1 among the 27 independent transconjugants (Figure 2). Seven of the 15 sites were described previously [10], and eight additional sites are reported here. There appears to be no absolute bias for the orientation of ICEBs1 insertions with respect to the direction of the replication forks, although 10 of the 15 insertions were oriented such that the direction of ICEBs1 replication was co-directional with the direction of the chromosomal replication forks (Figure 2A). Of the 27 independent transconjugants, 11 (41%) had ICEBs1 inserted in a site in yrkM (designated yrkM::ICEBs1) (Figure 2B), a gene of unknown function. Three of the 27 (11%) transconjugants had ICEBs1 inserted in a site in mmsA (encoding an enzyme involved in myo-inositol catabolism [20]). The site in yrkM is the most similar to the primary attachment site attB, differing by two base pairs. The site in mmsA differs from attB by three base pairs (Figure 2B). Two insertions were in a site in yqhG, although in opposite orientations. These are counted as two different sites since the sequence in each orientation is different (Figure 2B). The remaining 11 insertions were in unique sites, either in genes or intergenic regions (Figure 2B). None of the identified insertions caused a noticeable defect in cell growth in rich (LB) or defined minimal medium when ICEBs1 was repressed. Furthermore, none of the insertions were in tRNA genes (including redundant, nonessential tRNA genes) that are common integration sites for many ICEs [8], [9].

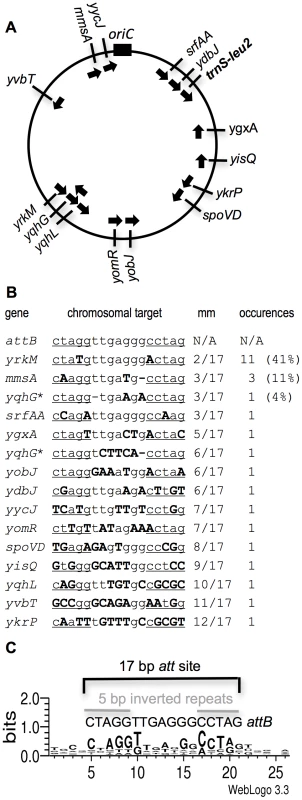

Fig. 2. Map and DNA sequence of the primary and 15 secondary integration sites for ICEBs1.

A. Approximate position of the primary and 15 secondary ICEBs1 integration sites on the B. subtilis chromosome. The circle represents the B. subtilis chromosome with the origin of replication (oriC) indicated by the black rectangle at the top. The slash marks represent the approximate location of the ICEBs1 insertion site. The name of the gene near which (ygxA) or into which (all other locations) ICEBs1 inserted is indicated on the outside of the circle. The arrows on the inside of the circle indicate the direction of ICEBs1 replication for each insertion. trnS-leu2 (in bold) contains the primary ICEBs1 integration site attB. B. DNA sequence of the primary and 15 secondary integration sites. The gene name is indicated on the left, followed by the DNA sequence (chromosomal target). The primary attachment site (attB) is a 17 bp sequence with 5 bp inverted repeats (underlined) separated by a 7 bp spacer. Mismatches from attB are indicated in bold, capital letters. “mm” indicates the number of mismatches from the primary 17 bp attB. “occurrences” indicates the number of independent times an insertion in each site was identified. Percentages of the total (27) are indicated in parenthesis. The * next to yqhG indicates that two different ICEBs1 insertions were isolated in this gene, once in each orientation. C. Sequence logo of the ICEBs1 secondary attachment sites. Using Weblogo 3.3 [21], we generated a consensus motif of the 26 bases surrounding the insertion site of the 15 secondary insertion sites for ICEBs1. For comparison, the primary attachment site for ICEBs1 is a 17 bp region with 5 bp inverted repeats and a 7 bp spacer region in the middle [10]. The size of each nucleotide corresponds to the frequency with which that nucleotide was observed in that position in the secondary attachment sites. Some of the secondary insertion sites were similar to and others quite different from the primary ICEBs1 attachment site (attBICEBs1, or simply attB). attB contains a 17 bp stem-loop sequence consisting of a 5 bp inverted repeat separated by 7 bp (Figure 2C). We aligned and compared the sequences of the 15 different secondary attachment sites and searched for a common motif using WebLogo 3.3 (http://weblogo.threeplusone.com/) [21]. For each secondary attachment site, we provided an input of 26 bp that included the region of the stem-loop sequence (17 bp, inferred from the sequence of attB) and a few base pairs upstream and downstream. The conserved sequences were largely in the 17 bp that were originally proposed to comprise attB [10], including several positions in the loop region of the stem-loop sequence, the 5 bp inverted repeats, and perhaps 1–2 additional base pairs downstream of the stem-loop (Figure 2C). There was considerable sequence diversity among the 15 secondary integration sites and the primary site attB, and no single position was conserved in all the secondary sites (Figure 2B). In some cases (e.g., insertions in yrkM, mmsA, yqhG, and srfAA) there are only 2–3 base pairs that are different between the secondary site and attB. In contrast, insertion sites in yghL, yvbT, and ykrP have 10–12 mismatches (out of 17 bp) from the sequence of attB (Figure 2B). These results indicate that in the absence of the primary integration site in trnS-leu2, ICEBs1 can integrate into many different sites throughout the genome, albeit at a lower efficiency [10]. Based on the diversity of the observed secondary attachment sites and the number of sites identified only once, it is clear that we have not identified all of the possible secondary integration sites for ICEBs1.

Integration into the secondary site in ykrM in the presence of a functional attB

We wondered if ICEBs1 could insert into a secondary site in cells in which the primary site, attB, is intact. To test this, ICEBs1 (from donor strain KM250) was transferred by conjugation to an ICEBs1-cured recipient that contained attB (strain KM524). Transconjugants were selected on solid medium and ∼108 independent transconjugants were pooled. DNA from the pooled transconjugants was then used as a template for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) with primers that detected ICEBs1 integrated into yrkM (the most frequently used secondary site). We found that the frequency of integration into yrkM was ∼10−4 to 10−3 of that into attB. As a control, we performed reconstruction experiments. Known amounts of DNA from two strains, one containing an insertion in yrkM (strain KM72), and the other containing an insertion in attB (strain AG174) were mixed and used as a template in qPCR, analogous to the experiment with DNA from the pooled transconjugants. These reconstruction experiments validated the results determined for the frequency of insertion into yrkM.

Excision of ICEBs1 from secondary integration sites is reduced

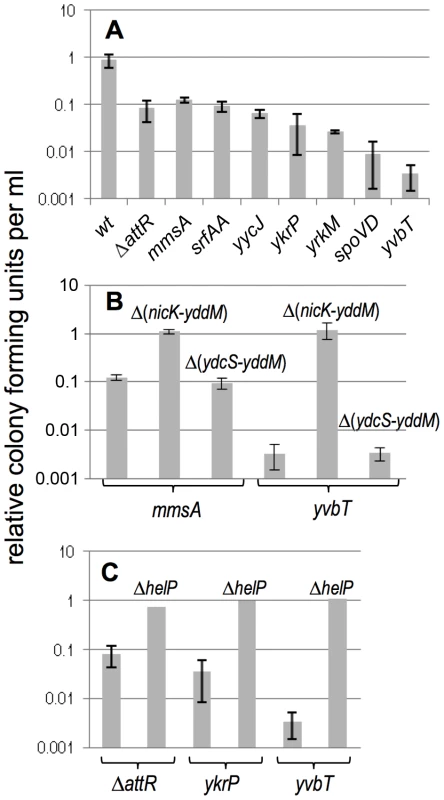

We wished to determine if there were any deleterious consequences of integration of ICEBs1 into secondary attachment sites. We found that although ICEBs1 integrated into the secondary integration sites, excision from all of the secondary sites we analyzed was reduced or eliminated. We monitored excision from seven of the secondary sites by overexpressing the activator of ICEBs1 gene expression, RapI, from a regulated promoter (Pxyl-rapI) integrated in single copy in the chromosome at the nonessential gene amyE (Materials and Methods). Overproduction of RapI induces ICEBs1 gene expression [11], [22] and typically results in excision of ICEBs1 from attB in >90% of cells within 1–2 hrs [10], [15]. Following a similar protocol as described for monitoring excision from attB [11], [15], [22], we performed qPCR using genomic DNA as template and primers designed to detect the empty secondary attachment site that would form if the element excised. In a positive control, excision of ICEBs1 from attB occurred in >90% of cells within two hours after expression of the activator RapI (Figure 3A, wt). In a negative control, excision of an ICEBs1 ΔattR mutant (Figure 1C), integrated in attB, was undetectable (Figure 3A, ΔattR). Excision from four of the sites tested, yrkM, mmsA, srfAA, and yycJ, was reduced yet still detectable, ranging from 4% to 15% of that of ICEBs1 from attB. Excision from the other three sites tested, yvbT, spoVD, and ykrP, was undetectable (Figure 3A), similar to what we observed for ICEBs1 ΔattR, the excision-defective control. In general, the secondary integration sites that are most divergent from attB had the least amount of excision (Table 1).

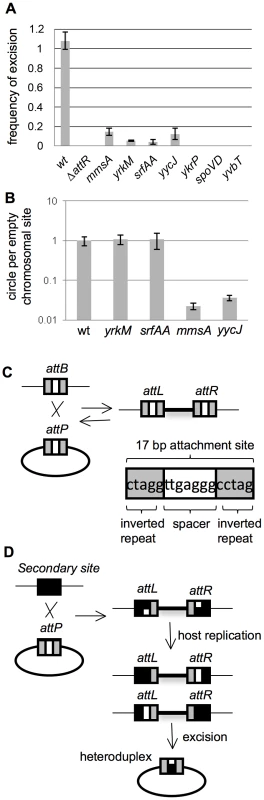

Fig. 3. Excision of ICEBs1 from secondary attachment sites.

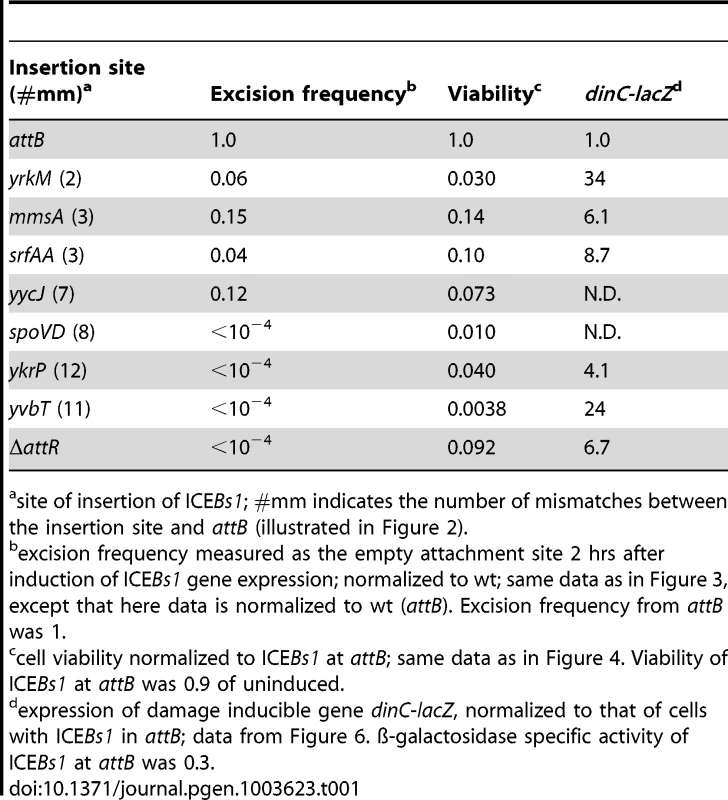

A–B. Excision frequencies and relative amounts of the excision products (circular ICEBs1 and empty chromosomal site) were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were grown in defined minimal medium with arabinose as carbon source. Products from excision were determined two hours after addition of xylose to induce expression of Pxyl-rapI to cause induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. Primers for qPCR were unique to each attachment site. Strains used include: wt, that is, ICEBs1 inserted in attB (CAL874); ΔattR, ICEBs1 integrated in attB, but with the right attachment site deleted and ICEBs1 unable to excise (Figure 1) (CAL872); mmsA::ICEBs1 (KM70); yrkM::ICEBs1 (KM72); srfAA::ICEBs1 (KM141); yycJ::ICEBs1 (KM132); ykrP::ICEBs1 (KM77); spoVD::ICEBs1 (KM130); yvbT::ICEBs1 (KM94). Each strain was assayed at least three times (biological replicates) and qPCR was done in triplicate on each sample. Error bars represent standard deviation. A. Frequency of excision of ICEBs1 from the indicated site of integration. The relative amount of the empty chromosomal attachment site was determined and normalized to the chromosomal gene cotF. Data were also normalized to a strain with no ICEBs1 (JMA222), which represents 100% excision. B. Relative amount of circular ICEBs1 compared to the amount of empty chromosomal attachment site for the indicated insertions. The relative amount of the ICEBs1 circle, normalized to cotF, was divided by the relative amount of the empty attachment site, also normalized to cotF. These ratios were then normalized to those for wild type. C. Cartoon of integration of ICEBs1 into its primary bacterial attachment site attB. attB is identical to the attachment site on ICEBs1, attICEBs1. They consist of a 17 bp region with 5 bp inverted repeats (gray boxes) on each side of a 7 bp spacer region (white box). During integration and excision, a recombination event occurs in the 7 bp spacer (crossover) region [38]. D. Cartoon of integration of ICEBs1 into secondary integration sites. A secondary integration site is indicated with a black box. When ICEBs1 integrates into a secondary site, the crossover regions in attICEBs1 and that of the secondary site are not necessarily identical, potentially creating a mismatch. This mismatch, if not repaired, will be resolved by host replication, generating left and right ends with different crossover sequences. Excision would then create a circular ICEBs1 with a heteroduplex in the attachment site on ICEBs1. Tab. 1. Summary of properties of several ICEBs1 insertions in secondary attachment sites.

site of insertion of ICEBs1; #mm indicates the number of mismatches between the insertion site and attB (illustrated in Figure 2). These findings indicate that integration of ICEBs1 into sites other than attB causes a reduction, sometimes quite severe, in the ability of the element to excise. Because excision is required for transfer of a functional ICE, this reduced excision will limit the spread of ICEBs1 that has inserted into secondary sites from which it cannot escape.

Decreased conjugation of ICEBs1 from secondary sites

We measured the mating efficiencies of ICEBs1 following excision from the four secondary attachment sites from which excision was reduced but detectable. Excision of ICEBs1 is required for transfer of the element to recipient cells. Thus, if the ICEBs1 circle is stable, then the mating efficiencies should be proportional to the excision frequency. The mating efficiencies of ICEBs1 from yrkM and srfAA were ∼2–5% of that of ICEBs1 from attB. Likewise, the excision frequencies of ICEBs1 inserted in yrkM and srfAA were ∼5% of those of ICEBs1 in attB. These results indicate that for ICEBs1 integrated in yrkM and srfAA, the mating efficiencies were approximately what was expected from the reduced excision frequencies.

In contrast, the mating efficiencies of ICEBs1 that excised from mmsA or yycJ were reduced beyond what would be expected from the already lowered excision frequency. In both cases, the excision frequencies were ∼15% of that of ICEBs1 integrated in attB. However, the mating efficiencies were ∼0.2% of that of ICEBs1 from attB, a 75-fold difference. Based on this result, we postulated that the reduced mating efficiency relative to the excision frequency was indicative of a reduction in the amount of circular ICEBs1.

Reduced levels of circular ICEBs1 from secondary sites that generate a heteroduplex

We measured the relative amounts of circular ICEBs1 after excision from yrkM, srfAA, mmsA, and yycJ, the four insertions with reduced but detectable excision, using qPCR primers designed to detect only the circular form of ICEBs1. The relative amounts of each circle were compared to the relative amount of the empty secondary attachment site from which ICEBs1 excised. Measurements were made two hours after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression (overproduction of RapI).

As expected, the ratio of the amounts of the circular form to the empty attachment site was about the same for insertions in yrkM and srfAA as for an insertion in attB (Figure 3B). In contrast, the ratio of the circle to the empty attachment site for mmsA and yycJ was significantly less than that for wild type (Figure 3B). Comparing the total amount of the ICEBs1 circle from mmsA and yycJ to that from attB indicated that there was approximately 0.3% as much circle from each site as from attB. This decrease in the amount of ICEBs1 circle is consistent with and likely the cause of the drop in mating efficiency to approximately 0.2% of that of ICEBs1 from attB.

The decrease in the amount of circular ICEBs1 from mmsA and yycJ is likely due to the generation of a heteroduplex in the attachment site on the circular ICEBs1. The ICEBs1 attachment site contains a 17 bp sequence with a 7 bp spacer region between 5 bp inverted repeats. Integrase-mediated site-specific recombination occurs in the 7 bp spacer (the crossover region) [10] (Figure 3C). If the 7 bp region in a chromosomal attachment site is different from that in ICEBs1, as is the case for mmsA and yycJ, then integration and host replication will create left (attL) and right (attR) ends that have different crossover regions (Figure 3D). Upon excision, these elements are predicted to contain a heteroduplex in the attachment site on the excised circular ICEBs1. Of the four insertions that have readily detectable excision frequencies, two (mmsA and yycJ) are predicted to form a heteroduplex and two (yrkM and srfAA) are not. In the case of mmsA::ICEBs1, the left and right ends are known to have different sequences [10].

Together, our results indicate that excision of ICEBs1 from secondary sites from which a heteroduplex is formed leads to lower levels of the circular ICEBs1 heteroduplex and a reduction in the ability of ICEBs1 to transfer to other cells. We do not yet know what causes the lower amounts of the ICEBs1 heteroduplex. Loss of the DNA mismatch repair gene mutS did not alter the instability of the ICEBs1 heteroduplex (unpublished results), indicating that mismatch repair is not solely responsible for this effect. Nonetheless, the overall reduction in transfer is due to both decreased excision and further decreased amounts of the excised element. Both of these defects provide barriers to the spread of ICEBs1 from secondary attachment sites.

ICEBs1 returns to attB following excision and conjugation from secondary sites

We found that when ICEBs1 excises from a secondary site and transfers to wild type cells via conjugation it tends to integrate in the primary attachment site, attB, and not in a secondary site. Donors with ICEBs1 in yrkM, mmsA, yycJ, and srfAA were crossed with a recipient (strain KM110) containing attB (and all known secondary sites). Individual transconjugants from each cross were isolated and tested by PCR for the presence of ICEBs1 in attB. ICEBs1 was present in attB in 9 of 10 transconjugants from yrkM::ICEBs1 donors, 9 of 9 transconjugants from mmsA::ICEBs1 donors, 9 of 10 transconjugants from yycJ::ICEBs1 donors, and 10 of 10 transconjugants from srfAA::ICEBs1 donors. In the two cases where ICEBs1 was not in attB, it was not present in the secondary site from which it came. We confirmed, using PCR primers internal to ICEBs1, that ICEBs1 was present in the transconjugants. Thus, we conclude that even if ICEBs1 is able to excise from a secondary attachment site, there is a strong bias in returning to the primary site if that site is present in a transconjugant.

We also found that if attB is not present in recipients during conjugation, then ICEBs1 integrates into a secondary attachment site, but with no apparent bias for the site from which it originated. We crossed donors with ICEBs1 in yrkM, mmsA, and srfAA with a recipient missing attB (strain KM111), and tested individual transconjugants for integration into the cognate site from which ICEBs1 excised in the donor. With the yrkM::ICEBs1 donor, 1 of 6 transconjugants had ICEBs1 in yrkM. With the mmsA::ICEBs1 donor, none of the 10 transconjugants tested had ICEBs1 integrated in mmsA. With the srfAA::ICEBs1 donor, none of the four transconjugants tested had ICEBs1 in srfAA. Together, these results indicate that ICEBs1 has a strong preference to integrate into attB, even when it starts from a secondary site, and that if attB is not available, ICEBs1 tends to go to a secondary site, with no apparent preference for the original location.

Decreased proliferation and viability of strains in which ICEBs1 has decreased excision

We found that strains with ICEBs1 in secondary integration sites had a decreased ability to form colonies when ICEBs1 gene expression was induced. We measured colony forming units (CFUs) of several strains with excision-defective (meaning reduced or no detectable excision) ICEBs1 insertions, including ICEBs1 in secondary sites and ICEBs1 ΔattR (in attB), both with and without induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. We also measured CFUs of wild type ICEBs1 (with normal excision frequencies) integrated at attB under similar conditions (Figure 4A). In the absence of RapI expression, when most ICEBs1 genes are repressed, growth and viability of excision-defective strains were indistinguishable from that of excision-competent strains. In contrast, by three hours after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in excision-defective ICEBs1 strains (ΔattR with ICEBs1 in attB, or insertions in mmsA, yrkM, srfAA, yycJ, spoVD, yvbT, and ykrP), the number of CFUs was reduced compared to that of the excision-competent ICEBs1 (in attB) (Figure 4A). These results are consistent with previous observations that excision-defective int and xis null mutants have a viability defect when RapI is overproduced [10].

Fig. 4. Effects of induction of ICEBs1 gene expression on cell viability.

The effects of induction of ICEBs1 gene expression on cell viability are shown for the indicated insertions and their derivatives. Cells were grown in defined minimal medium with arabinose to early exponential phase (OD600∼0.05) and xylose was added to induce expression of Pxyl-rapI, causing induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. The number of colony forming units was measured three hours after induction and compared to cells grown in the absence of xylose (uninduced). All experiments were done at least three times, except for the helP mutants (panel C), which were done twice with similar results. Data presented are averages of the replicates. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three replicates. A. Drop in viability of strains in which excision of ICEBs1 is defective. Strains used include: wt, that is, attB::ICEBs1 (CAL874); attB::ICEBs1 ΔattR::tet (CAL872); mmsA::ICEBs1 (KM70); srfAA::ICEBs1 (KM141); yycJ::ICEBs1 (KM132); ykrP::ICEBs1 (KM77); yrkM::ICEBs1 (KM72); spoVD::ICEBs1 (KM130); yvbT::ICEBs1 (KM94). B. Data are shown for two secondary insertion sites (mmsA::ICEBs1 and yvbT::ICEBs1). Similar results were obtained with ykrP::ICEBs1 and srfAA::ICEBs1 (data not shown). Derivatives of each insertion that delete nicK and all downstream ICEBs1 genes (ΔnicK-yddM) or that leave nicK intact and delete just the downstream genes (ΔydcS-yddM) (Figure 1) were tested. Strains used include: mmsA::ICEBs1 (KM70); mmsA::{ICEBs1 Δ(nicK-yddM)::cat} (KM366); mmsA::{ICEBs1 Δ(ydcS-yddM)::cat} (KM358); yvbT::ICEBs1 (KM94); yvbT::{ICEBs1 Δ(nicK-yddM)::cat} (KM369); yvbT::{ICEBs1 Δ(ydcS-yddM)::cat} (KM362). Data for KM70 and KM94 are the same as those shown above in panel A and are shown here for comparison. C. The ICEBs1 helicase processivity protein encoded by helP is required for cell killing by ICEBs1. Data are shown for two secondary integration sites (ykrP and yvbT) and the excision defective ICEBs1 ΔattR. The helP allele is a non-polar deletion [19]. Strains used include: attB::(ICEBs1 ΔattR::tet) (CAL872); attB::(ICEBs1 ΔhelP ΔattR::tet) (KM437); ykrP::ICEBs1 (KM77); ykrP::(ICEBs1 ΔhelP) (KM429); yvbT::ICEBs1 (KM94); yvbT::(ICEBs1 ΔhelP) (KM459). Data for KM94, KM77, and CAL872 are the same as those shown above in panel A and are shown here for comparison. Induction of ICEBs1 in several of the secondary integration sites (insertions in mmsA, srfAA, yycJ and ICEBs1 ΔattR in attB) caused a drop in CFU/ml to ∼10% of that of strains without ICEBs1 induction or the strain with wild type ICEBs1 at attB (Figure 4A). Induction of ICEBs1 in other insertion sites (ykrP, yrkM, spoVD, yvbT) caused a more severe drop in viability. The differences in CFU/ml between induced and uninduced cells (three hours after induction) appeared to be the combined effects of both a defect in proliferation (cell division) and cell death (viability). At times ≥3 hrs after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression, the number of CFU/ml dropped to below that before induction of gene expression, indicating that preexisting cells lost viability. For simplicity, we use “viability” to refer to both cell death and the decreased proliferation.

The drop in viability after induction of ICEBs1 in the various insertions did not correlate with dissimilarity of the attachment sites to attB or to the amount of residual excision in the excision-defective strains. For example, the ICEBs1 ΔattR mutant is completely unable to excise, and viability is ∼10% three hours after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. In contrast, ICEBs1 inserted into yrkM has about 5% excision after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression and viability is ∼3% (Table 1). Together, these results indicate that something about the specific locations of the insertions is likely causing the more extreme viability defect observed in some of the excision-defective ICEBs1 strains.

One of the most extreme effects on viability after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression is from the insertion in yvbT. Within three hours after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in the yvbT::ICEBs1 strain, viability was ∼0.3% of that of strains without ICEBs1 induction or of the strain with excision-competent ICEBs1 (Figure 4A). yvbT gene product is predicted to be similar to alkanal monooxygenases (luciferases). Insertion of ICEBs1 in yvbT likely knocks out yvbT function, so it seemed possible that the loss of yvbT combined with induction of ICEBs1 gene expression was causing the severe drop in viability. To test this hypothesis, we deleted yvbT in cells containing ICEBs1 inserted into mmsA and tested for viability after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. There was no additional drop in viability of the mmsA::ICEBs1 yvbT null mutant compared to the mmsA::ICEBs1 secondary site alone (wild type yvbT), either with or without induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. Based on these results, we conclude that the severe defect in viability of the yvbT::ICEBs1 secondary site mutant was not due to the loss of yvbT function combined with induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. It is also possible the severe drop in viability was due to production of a fragment of the yvbT gene product. This possibility seems highly unlikely because the putative fragment alone does not cause a phenotype, rather the drop in viability requires both induction and replication (see below) of ICEBs1. In addition, other insertions also caused a severe drop in viability and it is highly unlikely that each one of these is producing a toxic protein fragment.

We do not know what causes the more severe drop in viability in some insertions. However, the decrease in cell proliferation and viability caused by expression of ICEBs1 in secondary attachment sites should provide selective pressure against the long term survival of these strains. The more severe the loss in viability, the stronger the selective pressure against long term survival of strains with insertions in these sites. Suppressor mutations that alleviate the drop in viability are readily obtained (KLM, C. Lee, ADG, data not shown), although most of these mutations have not been characterized.

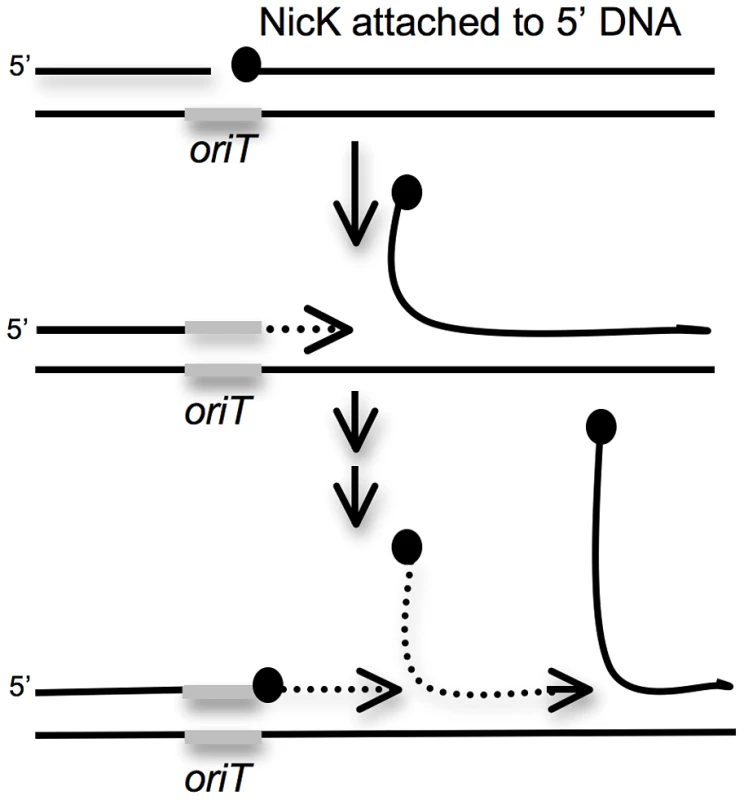

ICEBs1 replication functions are required for the drop in viability of excision-defective insertions

Because the drop in proliferation and viability in the first few hours after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression occurs in ICEBs1 excision-defective and not in excision-competent strains, the decreased viability is likely due to a cis-acting property of ICEBs1 and not a diffusible ICEBs1 product. One of the more dramatic changes following induction of ICEBs1 gene expression is induction of multiple rounds of unidirectional rolling circle replication [15]. This replication initiates from the ICEBs1 origin of transfer oriT, requires the ICEBs1 relaxase encoded by nicK and the helicase processivity factor encoded by helP (previously ydcP) [19]. Rolling circle replication of ICEBs1 occurs even when ICEBs1 is unable to excise from the chromosome as observed previously for a mutant unable to excise [15]. Therefore, we expected that induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in the secondary site insertions would lead to unidirectional rolling circle replication from oriT in the host chromosome (Figure 5). It seemed likely that this replication could cause damage to the chromosome and lead to the decrease in cell viability.

Fig. 5. Cartoon of repeated rolling-circle replication from the ICEBs1 oriT that is stuck in the chromosome.

Rolling circle replication is induced in ICEBs1 insertions that are unable to excise from the chromosome. During this replication, the ICEBs1 relaxase NicK (black circles) nicks a site in oriT, the origin of transfer (gray bar) that also functions as an origin of replication [15], [23]. NicK presumably becomes covalently attached to the 5′ end of the nicked DNA. Replication extends (dotted line with arrow) from the free 3′-end, and regenerates a functional oriT that is a substrate for another molecule of NicK. The only other ICEBs1 product needed for ICEBs1 replication is the helicase processivity factor HelP [19]. The rest of the replication machinery (not shown) is composed of host-encoded proteins. We tested nicK and the genes downstream for effects on cell viability following induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in the excision-defective insertions. Preliminary experiments indicated that loss of nicK restored viability after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. However, this effect could have been due to polarity on downstream genes. Unfortunately, nicK null mutants are difficult to fully complement [23], perhaps because NicK might act preferentially in cis. In addition, complementation of other supposedly “non-polar” mutations in ICEBs1 are not complemented fully [19], [24]. Therefore, to test if loss of nicK was responsible for the suppression of lethality, or if the suppression was due to loss of expression of a downstream gene, we compared two different deletions in ICEBs1. One deletion removed nicK and most of the downstream genes {Δ(nicK-yddM)} (Figure 1D). In the second deletion, nicK was intact, but most of the genes downstream from oriT and nicK were removed {Δ(ydcS-yddM)} (Figure 1E).

We found that deletion of nicK alleviated the growth defect of excision-defective secondary insertions, including mmsA::ICEBs1 and yvbT::ICEBs1 that caused the most severe drop in viability (Figure 4B). Deletion of the genes downstream from nicK did not alleviate the drop in viability (Figure 4B), indicating that expression of these genes (many encoding conjugation functions) was not the cause of the decreased cell viability. In addition, in preliminary experiments, we found that several suppressor mutations that restore viability to an excision-defective ICEBs1 (in this case, at attB) were null mutations in nicK (C. Lee, ADG, unpublished results). Together, these results indicate that a NicK-dependent process is causing the drop in viability of the excision-defective ICEBs1.

NicK creates a nick at a specific site in ICEBs1 oriT [23], and nicking is required for ICEBs1 replication (and conjugation) [15]. To determine if the drop in cell viability was due to nicking per se, or to replication, we used a recently defined ICEBs1 gene, helP, which encodes a helicase processivity factor that is needed for ICEBs1 replication but not for nicking [19], [23]. Deletion of helP (Figure 1F) is not polar on nicK and does not affect nicking at oriT [19]. Deletion of helP completely alleviated the growth defect associated with induction of ICEBs1 (Figure 4C).

Based on these results, we conclude that unidirectional rolling circle replication from oriT in the chromosome most likely caused the drop in viability of the excision-defective ICEBs1. The decrease in viability could be due to breaks and degradation of chromosomal DNA around the site of insertion and/or disruptions in host chromosomal replication caused by the multiple rounds of rolling circle replication from oriT (Figure 5).

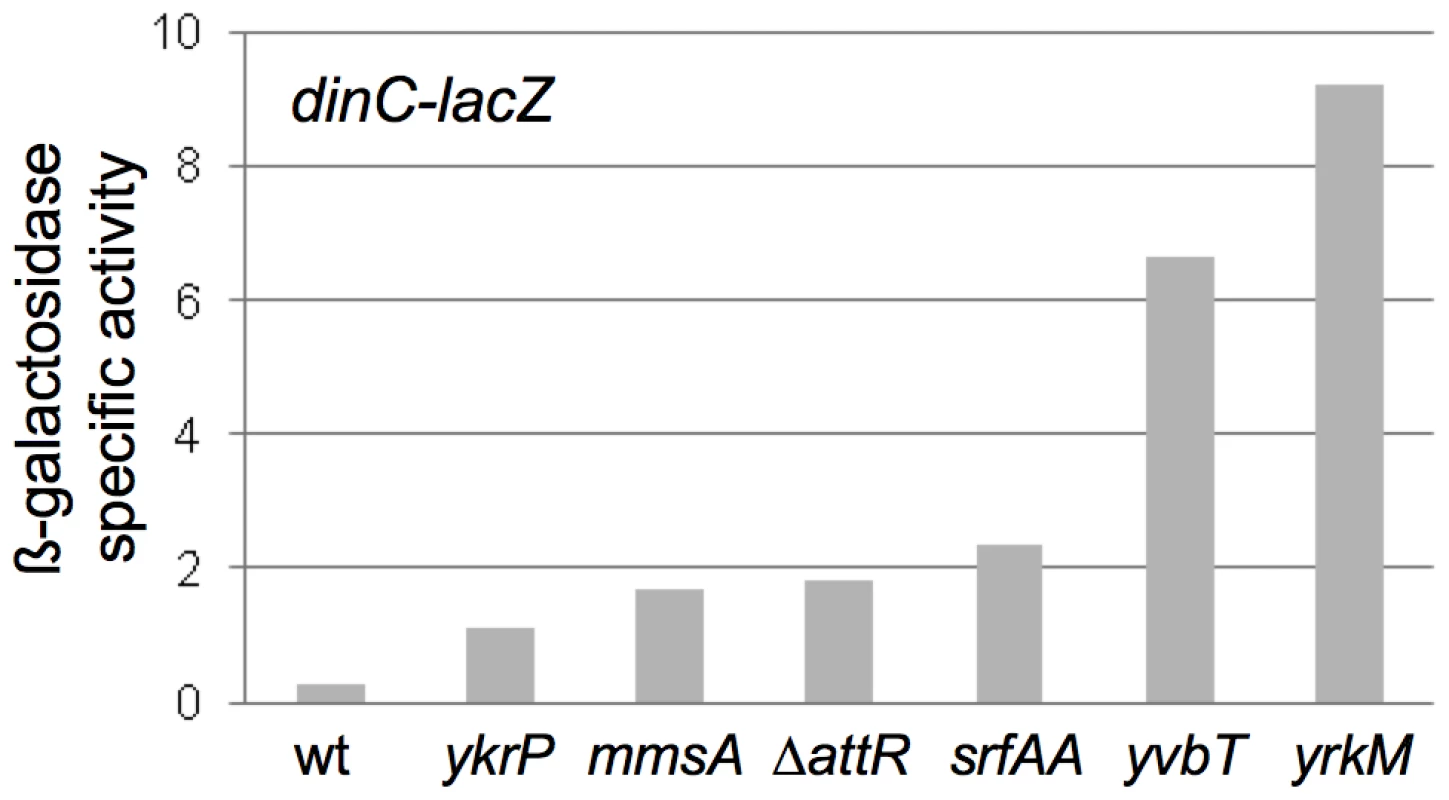

Induction of the SOS response in strains in which ICEBs1 is defective in excision

We found that induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in the excision-defective insertions caused induction of the host SOS response. Like that in other organisms, the SOS response in B. subtilis results in increased expression of a large set of genes in response to DNA damage or replication stress [25]. We used a lacZ fusion to a damage-inducible gene, dinC-lacZ [26], [27], to monitor the SOS response in cells following induction of ICEBs1. Without induction of ICEBs1 gene expression, there was no detectable ß-galactosidase activity above background levels, indicating that none of the insertions alone caused elevated SOS gene expression. In all of the excision-defective ICEBs1 strains analyzed (ICEBs1 ΔattR in attB, and insertions in mmsA, yvbT, ykrP, srfAA, and yrkM), there was a ≥3.5-fold increase in ß-galactosidase levels from the dinC-lacZ fusion 3 hrs after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression (Figure 6). In contrast, there was no detectable increase in ß-galactosidase activity three hrs after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in the excision-competent insertion in attB (Figure 6). There was no apparent correlation between the amount of SOS induction and the severity of the viability defect. For example, one of the strains with the most severe viability defect (ICEBs1 in ydcP) had a relatively low amount of expression of dinC-lacZ (Figure 6). However, the amount of SOS induction could be an underestimate since many cells in the population lose viability.

Fig. 6. Induction of the SOS response.

The ß-galactosidase specific activities from the SOS transcriptional reporter fusion dinC-lacZ in strains with ICEBs1 in the indicated secondary attachment sites are presented. Strains were grown as described in Figure 4 and samples for ß-galactosidase assays were taken 3 hours after induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. Data presented are the averages of two biological replicates (four for ΔattR strain KM392)). For all of the strains with insertions in secondary attachment sites, the values from the biological replicates were within 20% of the average. Strains used include: wt, attB::ICEBs1 (KM390); ykrP::ICEBs1 (KM402); mmsA::ICEBs1 (KM394); attB::ICEBs1 ΔattR::tet (KM392); srfAA::ICEBs1 (KM400); yvbT::ICEBs1 (KM396); yrkM::ICEBs1 (KM404). Induction of dinC-lacZ in the strains with ICEBs1 in secondary attachment sites was consistent with prior preliminary experiments using DNA microarrays that indicated induction of the SOS response in ICEBs1 int and xis mutants that are incapable of excision (N. Kavanaugh, C. Lee, ADG, unpublished results). Based on these results, we conclude that induction of ICEBs1 gene expression in cells in which ICEBs1 is stuck in the chromosome causes DNA damage that induces the host SOS response. However, the SOS response per se is not what caused cell death.

Discussion

We isolated and characterized insertions of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of B. subtilis into secondary integration (attachment or insertion) sites. Secondary integration sites appear to be used naturally, even in the presence of the primary site, at a frequency of ∼10−4 to 10−3 of that of the primary site, indicating that approximately 100–1,000 cells in a population of ∼106 transconjugants will have ICEBs1 at a secondary site. We found that insertions in secondary sites are detrimental for the propagation of ICEBs1 and detrimental to the survival of the host cells. These detrimental effects likely provide selective pressure to maintain the already established site-specificity. Below we discuss target site selection among ICEs, aspects of ICEBs1 biology that make insertions into secondary sites detrimental, and the more general implications for the evolution of ICEs.

Target site selection and maintenance of tRNA genes as integration sites

We have identified 15 different secondary insertion sites for ICEBs1. Some of these sites are similar to the primary attachment site, but some are quite different. Based on the diversity of sites, and the isolation of only a single insertion in many of them, it is likely that we are nowhere near saturation for identifying all possible sites in non-essential regions. Given that there is some sequence conservation among the secondary sites, DNA sequence is clearly important in the potential function as an integration site. However, we suspect that other factors also contribute. These factors could include possible roles for nucleoid binding proteins, other DNA binding proteins, transcription, and local supercoiling.

Many site-specific ICEs have preferred integration sites in tRNA genes. This preference is thought to occur, at least in part, because tRNA genes are highly conserved and contain inverted repeats that are typically used as integration targets for site-specific recombinases [9]. We postulate that the selective pressure to maintain site-specific integration in a tRNA gene comes from a combination of factors, including: the conservation of tRNAs, the ability of an ICE to efficiently excise from the primary attachment site, and the decreased cell viability and decreased ability of an ICE to spread when excision is reduced due to integration into a secondary site.

Selective pressures against ICEs in secondary attachment sites

Our results indicate that there are at least two main types of selective pressures against propagation of ICEBs1 that has inserted into a secondary integration site. First, there is strong pressure against the spread of that particular element due to the large defect in its ability to excise and the instability of circular ICEBs1 when it forms a heteroduplex. The excised circular form of an ICE is necessary for its complete transfer to a recipient cell. At least one other ICE has a reduced excision frequency from a secondary integration site. Excision of SXT from a secondary attachment site in Vibrio cholerae was reduced 3–4-fold relative to its ability to excise from the primary attachment site [28]. In addition, lysogenic phages can also have reduced excision efficiencies from secondary attachment sites [29]. Insertion of any type of mobile genetic element into a location from which it has trouble getting out will be deleterious to the further horizontal propagation of that element. Based on our results, this is particularly true for ICEBs1.

In addition to the defect in ICEBs1 excision and transfer from secondary integration sites, there is a decrease in cell viability following induction of ICEBs1 gene expression. ICEBs1 gene expression is normally induced under conditions of starvation or cell crowding when the activator RapI is expressed and active, or when the RecA-dependent SOS response is induced [22]. Induction of ICEBs1 gene expression causes rolling circle replication from the ICEBs1 origin of transfer oriT [15], [19]. Our results indicate that rolling circle replication from an element that is unable to efficiently excise from the chromosome causes a drop in cell viability. This drop is likely due to chromosomal damage and stalling of the chromosomal replication forks when they reach the complex structure formed by repeated initiation of rolling circle replication from oriT in the chromosome (Figure 5).

We suspect that autonomous replication is a common property of many ICEs but has not been generally observed because of the low frequency of induction and excision of most of these elements. There are indications that some other ICEs undergo autonomous replication [1], [16]–[18]. If autonomous replication of ICEs is widespread, as we postulate [15], [19], then there should be selective pressure against viability of cells in which an ICE is induced, replicates, and is unable to excise.

There were at least two different effects caused by replication of excision-defective elements. Replication from ICEBs1 in the chromosome caused a drop in cell viability of at least 10-fold, but sometimes caused a severe drop, 100–1000-fold in about 3 hrs. We do not know what causes this severe drop in viability, but it requires active replication of the ICEBs1 that is unable to excise from a specific chromosomal location. This severe drop in viability could be due to increased dosage of nearby genes or perhaps differential fragility of these chromosomal regions. In any case, the severe drop in viability provides even stronger selective pressure against propagation of the strains with insertions of ICEBs1 in these locations.

The growth defect associated with the secondary insertions is most obvious when ICEBs1 gene expression is induced. Cells with ICEBs1 insertions in secondary attachment sites might be purged from the population under natural conditions of induction, providing selective pressure against maintenance of integrants in secondary sites and favoring a site-specific strategy of integration and excision.

We estimated the effects of insertions in secondary sites in populations without experimentally induced activation of ICEBs1. The “spontaneous” activation and excision frequency of ICEBs1 in a population of cells is estimated to be approximately one cell in 104–105 [10], [22], [30]. Assuming a frequency of activation of ICEBs1 of ∼10−4 per generation, and that all activated cells with ICEBs1 in a secondary site die, we estimate that it would take ∼23,000 generations for a population of cells with ICEBs1 in a secondary site to be 0.1 times the size of a population of cells with ICEBs1 in the primary site. The activation frequency increases under several conditions likely to be more relevant than growth in the lab, including: the presence of cells without ICEBs1, entry into stationary phase, and during the SOS response [10], [11], [22]. For example, if activation of ICEBs1 actually occurs in 0.1% of cells, then it would take ∼2,300 generations for the secondary site insertion population to be 0.1 times the population of cells with ICEBs1 in the primary site. These effects are difficult to measure experimentally, but easy to see when ICEBs1 is efficiently induced.

ICEs with single versus multiple integration sites

ICEs of the Tn916/Tn1545 family can integrate into multiple sites in many organisms, yet they are not known to cause a defect in cell growth when gene expression is induced. Tn916 and most family members contain tetM, a gene encoding resistance to tetracycline. Expression of tetM and Tn916 genes is induced in the presence of tetracycline [31]. Tn916 has two helP (helicase processivity) homologues and we predict that it undergoes autonomous rolling circle replication [19]. Despite relatively low excision frequencies, tetracycline-induced Tn916 gene expression is not known to cause a drop in cell viability. Tetracycline induces expression of several Tn916 genes, including those needed for excision. However, the Tn916 relaxase (orf20), the two helP homologues (orf22 and orf23), and the conjugation genes are not expressed until Tn916 excises and circularizes [31]. Based on analogy to ICEBs1, we have postulated that Tn916 is capable of autonomous rolling circle replication [15] and that the relaxase (orf20) and at least one of the helP homologues are likely needed for this replication [19]. The regulation of Tn916 gene expression specifically prevents expression of these putative replication functions until after excision. Consequently, rolling circle replication of Tn916 cannot occur while the element is integrated in the chromosome. We speculate that some of the evolutionary pressures to establish and maintain a high degree of site specificity is lost when expression of ICE replication functions does not occur until after excision from the host genome.

Materials and Methods

Media and growth conditions

Bacillus subtilis was grown at 37°C in LB or defined S750 minimal medium with arabinose (1%) as carbon source. Antibiotics and other chemicals were used at the following concentrations: isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM), chloramphenicol (cat, 5 µg/ml), kanamycin (kan, 5 µg/ml), spectinomycin (spc, 100 µg/ml), erythromycin (0.5 µg/ml) and lincomycin (12.5 µg/ml) together, to select for macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance (mls or erm).

Bacillus subtilis strains and alleles

B. subtilis strains used are listed in Table 2. All except BTS14 are derived from AG174 (JH642) and contain mutations in trpC and pheA (not shown). Most of the strains were constructed using natural transformation or conjugation, as described below. Many alleles were previously described. dinC18::Tn917lac is an insertion in the damage-inducible gene dinC and creates a transcriptional fusion to lacZ [27]. Most ICEBs1 strains contained a kanamycin-resistance cassette {Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan} [11]. ICEBs1 was induced by overexpression of rapI from a xylose-inducible promoter using amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI), spc} [24] or from an IPTG-inducible promoter using amyE::{(Pspank(hy)-rapI), spc} [11]. ΔattR100::tet deletes 216 bp spanning the junction between the right end of ICEBs1 and the chromosome [10]. ΔhelP155 is an unmarked 413-bp deletion that removes the entire coding sequence and the 35 bp helP-ydcQ intergenic region (Figure 1F) [19].

Tab. 2. <i>B. subtilis</i> strains used.

ΔattB mutant with a compensatory mutation in trnS-leu1

ΔattB::cat is a deletion-insertion that is missing ICEBs1 and removes 185 bp that normally contains the primary chromosomal ICEBs1 attachment site, resulting in the loss of a functional trnS-leu2 [10]. Although trnS-leu2 is non-essential [10], [32], cells with ΔattB do not grow as well as wild type. To improve the growth of ΔattB::cat, we used a compensatory mutation in trnS-leu1 that changes the anti-codon to that normally found in trnS-leu2 (C. Lee, & ADG), analogous to the leuF1 mutation previously described [32]. The compensatory mutation was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using the overlap-extension PCR method [33]. Because trnS-leu1 and ΔattB::cat are genetically linked, we selected for chloramphenicol resistant colonies and screened for the single bp mutation in trnS-leu1 by sequencing. In addition to the mutant trnS-leu1 allele (trnS-leu1-522), the strain had an additional mutation, (5′-CAAAAAAACTAAA to 5′-CAAAAAAACTAAG) in the non-coding region between ΔattB::cat and yddN. Growth of the resulting strain, CAL522, was indistinguishable from that of wild type. This strain stably acquired ICEBs1 in conjugation experiments at a frequency ∼0.5% of that of wild type, approximately 10-fold lower than the strain without the compensatory mutation in trnS-leu1 [10]. We do not understand the cause of this reproducible difference.

Deletion of nicK and downstream genes

We constructed two large deletion-insertion mutations in ICEBs1, one removing nicK and all downstream genes, Δ(nicK-yddM)::cat, and the other leaving nicK intact, but removing the downstream genes, Δ(ydcS-yddM)::cat. Both deletions leave the ends of ICEBs1 intact (Figure 1D, E), have cat (chloramphenicol resistance) from pGEMcat [34], and were constructed using long-flanking homology PCR [35]. The Δ(nicK-yddM)::cat allele contains the first 127 bp in the 5′ end of nicK. The Δ(ydcS-yddM)::cat allele contains the first 29 bp in the 5′ end of ydcS. Both deletions (Figure 1) extend through the first 170 bp in yddM. The alleles were first transformed into wild type strain AG174. Chromosomal DNA was then used to transfer the alleles into other strains, including KM70 (mmsA::ICEBs1), KM94 (yvbT::ICEBs1), KM77 (ykrP::ICEBs1), KM141 (srfAA::ICEBs1), and CAL874 (ICEBs1 at attB). In all cases, the incoming deletion associated with cat replaced the Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan allele present in ICEBs1 in the recipient.

Deletion of yvbT in mmsA::ICEBs1

We constructed a deletion-insertion that removes the 19 bases before yvbT and the first 808 bp of yvbT, leaving the last 200 bp intact. The sequence from yvbT was replaced with cat, from pGEMcat [34], using long-flanking homology PCR [35]. The insertion-deletion was verified by PCR and the mutation was introduced into strain KM70 (mmsA::ICEBs1) by transformation.

Isolation and identification of secondary ICEBs1 integration sites

Mating ICEBs1 into a ΔattB recipient

Mating assays were performed essentially as described [10], [11]. Excision of a kanamycin resistant ICEBs1 (ICEBs1 Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan) was induced in the donor cells by overproduction of RapI from Pspank(hy)-rapI. Donors (resistant to kanamycin and spectinomycin) were mixed with an approximately equal number of recipients (resistant to chloramphenicol) and filtered on sterile cellulose nitrate membrane filters (0.2 µm pore size). Filters were cut into 8 pieces (so that transconjugants were independent isolates), placed on Petri plates containing LB and 1.5% agar, and incubated at 37°C for 3 hours. Cells from each piece of filter were streaked for independent transconjugants by selecting for the antibiotic resistance conferred by the incoming ICEBs1 (kanamycin) and the resistance unique to the recipient (chloramphenicol). The recipient used in this report {ΔattB::cat trnS-leu1-522} is different from the recipient {ΔattB::cat} used previously [10]. The trnS-leu1-522 confers normal growth to the ΔattB (ΔtrnS-leu2) mutant (see above).

Inverse PCR to identify the site of insertion of independent transonjugants

Identification of integration sites was done essentially as described previously [10]. Briefly, we used inverse PCR to amplify the junction between the chromosome and the right (yddM) end of ICEBs1 integrated into various secondary sites. Chromosomal DNA was digested with HindIII and approximately 50 ng was ligated in a 100 µl reaction to favor circularization of DNA fragments. One-fourth of the ligation reaction was used in inverse PCR with either of two primer pairs (CLO17-CLO58 or CLO50-oJMA97) designed to amplify the ICEBs1 and chromosomal sequences flanking yddM. PCR products were sequenced with primers CLO17, CLO50, oJMA207, and CLO114 (primers are described in Table 3). Comparison to the B. subtilis genome sequence indicated where ICEBs1 had integrated.

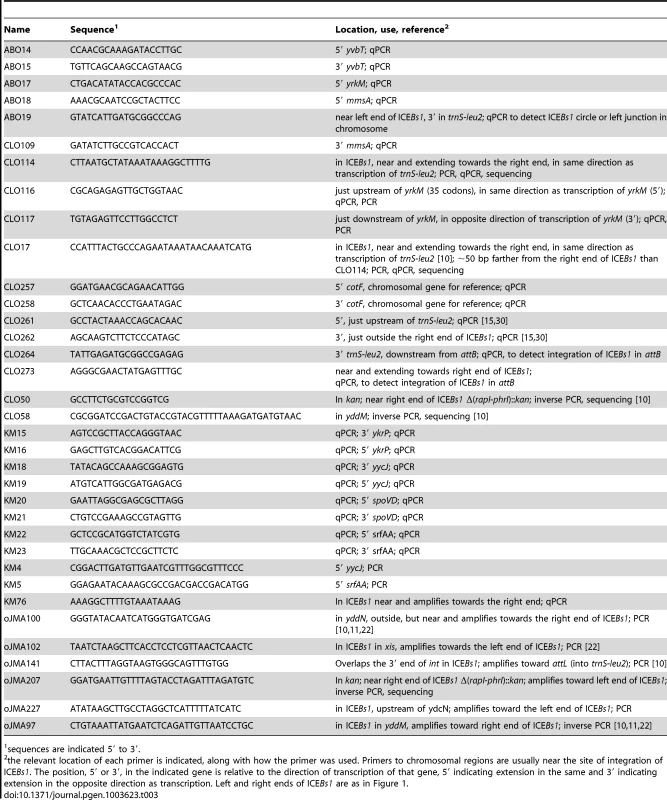

Tab. 3. Primers used.

sequences are indicated 5′ to 3′. Backcross of ICEBs1 insertions

Seven of the 15 different insertions of ICEBs1 in secondary attachment sites were initially chosen for further study. These were first backcrossed into a strain cured of ICEBs1 (JMA222). Pxyl-rapI (amyE::{(Pxyl-rap) spc}) was introduced into these strains by transformation and selection for spectinomycin resistance using chromosomal DNA from strain MMB869. We verified that ICEBs1 was still at the original secondary attachment site using PCR with site-specific primers. The final strains from these crosses include: KM70 (mmsA::ICEBs1), KM94 (yvbT::ICEBs1), KM72 (yrkM::ICEBs1), KM77 (ykrP::ICEBs1), KM130 (spoVD::ICEBs1), KM141 (srfAA::ICEBs1), and KM132 (yycJ::ICEBs1).

Assays for excision and integration of ICEBs1

Detecting excision from secondary insertions

Excision of ICEBs1 from a chromosomal attachment site creates an extrachromosomal ICEBs1 circle and an “empty” attachment site (also called “repaired chromosomal junction”). Each product was measured using specific primers for quantitative real time PCR (qPCR), using a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system with Syber Green detection reagents (Roche), essentially as described [15]. Cells were grown in defined minimal medium with arabinose as carbon source. Products from excision were determined two hours after addition of xylose to induce expression of Pxyl-rapI to cause induction of ICEBs1 gene expression.

The amount of each empty attachment site was compared to a chromosomal reference gene, cotF, measured with primers CLO257-CLO258. The amount of empty attachment site from each of the secondary sites was normalized to strain JMA222, an ICEBs1-cured strain that simulates 100% excision. Standard curves for qPCR with cotF and the repaired junction for each secondary insertion were generated using genomic DNA from JMA222. Primers (in parentheses) for empty secondary attachment sites were specific for: yrkM (CLO117-ABO17), mmsA (CLO109-ABO18), yycJ (KM18-KM19), srfAA (KM22-KM23), spoVD (KM20-KM21), yvbT (ABO14-ABO15), ykrP (KM154-KM16), and attB (CLO261-CLO262).

The amount of ICEBs1 circle that forms after excision from the chromosome was measured with primers AB019-CLO114. The amount of excised circle was compared to the chromosomal reference cotF (primers CLO257-CLO258), and normalized to the amount of excised circle from attB (strain CAL874). Standard curves for qPCR for cotF and the excised circle were generated using genomic DNA from RapI-induced CAL874. Primer sequences are presented in Table 3.

Detecting integration at yrkM in a pool of transconjugants

ICEBs1 was transferred from donor strain KM250 to recipient KM524 by conjugation, selecting for resistance to kanamycin and MLS antibiotics. Approximately 108 transconjugants were collected from four separate conjugation experiments (done on filters placed on agar plates). Cells were washed off of all four filters with a total of 10 ml of minimal salts and aliquots of 0.2 ml were spread on selective plates to give ∼2×106 transconjugants per plate. After overnight growth, plates (∼50) with the transconjugants were flooded with minimal salts, cells were scraped, collected, and transconjugants from all plates were pooled.

DNA was isolated from the pool of transconjugants and used as a template for qPCR with primers to detect the junction between yrkM and ICEBs1 (primers CLO116 and KM76). Values from this qPCR were compared to qPCR values for a reference gene (cotF). Values were normalized to a strain (KM72) that contains yrkM::ICEBs1 and represents 100% integration at yrkM. Values for yrkM::ICEBs1 in the pool of transconjugants were in the linear range of the qPCR and ≥3-fold above the background signal from the negative control (JMA222, which is cured of ICEBs1). DNA used for standard curves was from strain KM72 (yrkM::ICEBs1). The frequency of integration at attB was determined by qPCR with primers CLO273 and CLO264. Values were compared to cotF and normalized to a strain with ICEBs1 at attB (strain AG174 or CAL874). DNA used for standard curves was from AG174 or CAL874. The entire experiment was done twice with similar results.

Detecting integration at secondary sites after mating from a secondary site

Independent transconjugants, from donors with ICEBs1 at secondary attachment sites, were analyzed for the location of ICEBs1. Sites analyzed and primers used included: yrkM (CLO116-CLO17 or oJMA141-CLO17); mmsA (CLO109-oJMA141); yycJ (CLO17-KM4); srfAA (oJMA141-KM5); and attB (CLO17-oJMA100). The presence of ICEBs1 in the transconjugants was verified using primers internal to ICEBs1 (oJMA102-oJMA22).

Cell viability assays

Strains were grown in defined minimal medium with arabinose and expression of Pxyl-rapI was induced with 1% xylose at OD600 of 0.05. The number of colony forming units (CFU) was determined 3 hours after addition of xylose. For each strain, the number of CFU/ml 3 hrs after expression of Pxyl-rapI was compared to the number of CFU/ml without expression of Pxyl-rapI. All experiments were done at least twice.

ß-galactosidase assays

Cells were grown and treated as described for viability assays. Samples were taken 3 hours after induction of Pxyl-rapI. All experiments were done at least twice. ß-galactosidase assays were done essentially as described [36], [37]. Specific activity is expressed as the (ΔA420 per min per ml of culture per OD600 unit)×1000.

Modeling competition between cells with ICEBs1 in the primary attachment site versus cells with ICEBs1 in a secondary attachment site

We calculated the predicted population size P after G generations for cells in which ICEBs1 is integrated into a secondary attachment site, with an estimated fraction of dead cells, D. The estimate of dead cells is based on the fraction of cells in which ICEBs1 is excised during exponential growth, determined previously to be between 10−5 to 10−4. Population size P = P0•2G•(1−D)G, where P0 is the initial population size. The ratio R of the number of cells with ICEBs1 at attB to the number of cells with ICEBs1 in a secondary site is given by R = P0•2G (for ICEBs1 in attB and assuming no killing upon induction)/P0•2G•(1−D)G (for ICEBs1 in a secondary site). This equation reduces to R = 1/(1−D)G. This gives G = {log (1/R)}/log (1−D). For the number of cells with ICEBs1 in attB to be 10-fold greater than the number of cells with ICEBs1 in a secondary site (R = 10) and if the frequency of death if ∼10−4 for the secondary site insertions, then the number of generations to achieve R = 10 is: G = log(0.1)/log(0.9999) which is ∼23,000.

Zdroje

1. WozniakRA, WaldorMK (2010) Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat Rev Microbiol 8 : 552–563.

2. GuglielminiJ, QuintaisL, Garcillan-BarciaMP, de la CruzF, RochaEP (2011) The repertoire of ICE in prokaryotes underscores the unity, diversity, and ubiquity of conjugation. PLoS Genet 7: e1002222.

3. LeeCA, ThomasJ, GrossmanAD (2012) The Bacillus subtilis conjugative transposon ICEBs1 mobilizes plasmids lacking dedicated mobilization functions. J Bacteriol 194 : 3165–3172.

4. SalyersAA, ShoemakerNB, StevensAM, LiLY (1995) Conjugative transposons: an unusual and diverse set of integrated gene transfer elements. Microbiol Rev 59 : 579–590.

5. HochhutB, WaldorMK (1999) Site-specific integration of the conjugal Vibrio cholerae SXT element into prfC. Mol Microbiol 32 : 99–110.

6. RobertsAP, MullanyP (2009) A modular master on the move: the Tn916 family of mobile genetic elements. Trends Microbiol 17 : 251–258.

7. MullanyP, WilliamsR, LangridgeGC, TurnerDJ, WhalanR, et al. (2012) Behavior and target site selection of conjugative transposon Tn916 in two different strains of toxigenic Clostridium difficile. Appl Environ Microbiol 78 : 2147–2153.

8. BurrusV, WaldorMK (2004) Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements. Res Microbiol 155 : 376–386.

9. WilliamsKP (2002) Integration sites for genetic elements in prokaryotic tRNA and tmRNA genes: sublocation preference of integrase subfamilies. Nucleic Acids Res 30 : 866–875.

10. LeeCA, AuchtungJM, MonsonRE, GrossmanAD (2007) Identification and characterization of int (integrase), xis (excisionase) and chromosomal attachment sites of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 66 : 1356–1369.

11. AuchtungJM, LeeCA, MonsonRE, LehmanAP, GrossmanAD (2005) Regulation of a Bacillus subtilis mobile genetic element by intercellular signaling and the global DNA damage response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 12554–12559.

12. BurrusV, PavlovicG, DecarisB, GuedonG (2002) The ICESt1 element of Streptococcus thermophilus belongs to a large family of integrative and conjugative elements that exchange modules and change their specificity of integration. Plasmid 48 : 77–97.

13. FrankeAE, ClewellDB (1981) Evidence for conjugal transfer of a Streptococcus faecalis transposon (Tn916) from a chromosomal site in the absence of plasmid DNA. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 45 Pt 1 : 77–80.

14. FrankeAE, ClewellDB (1981) Evidence for a chromosome-borne resistance transposon (Tn916) in Streptococcus faecalis that is capable of “conjugal” transfer in the absence of a conjugative plasmid. J Bacteriol 145 : 494–502.

15. LeeCA, BabicA, GrossmanAD (2010) Autonomous plasmid-like replication of a conjugative transposon. Mol Microbiol 75 : 268–279.

16. SitkiewiczI, GreenNM, GuoN, MereghettiL, MusserJM (2011) Lateral gene transfer of streptococcal ICE element RD2 (region of difference 2) encoding secreted proteins. BMC Microbiol 11 : 65.

17. CarraroN, LibanteV, MorelC, DecarisB, Charron-BourgoinF, et al. (2011) Differential regulation of two closely related integrative and conjugative elements from Streptococcus thermophilus. BMC Microbiol 11 : 238.

18. RamsayJP, SullivanJT, StuartGS, LamontIL, RonsonCW (2006) Excision and transfer of the Mesorhizobium loti R7A symbiosis island requires an integrase IntS, a novel recombination directionality factor RdfS, and a putative relaxase RlxS. Mol Microbiol 62 : 723–734.

19. ThomasJ, LeeCA, GrossmanAD (2013) A conserved helicase processivity factor is needed for conjugation and replication of an integrative and conjugative element. PLoS Genet 9: e103198.

20. YoshidaK, YamaguchiM, MorinagaT, KineharaM, IkeuchiM, et al. (2008) myo-Inositol catabolism in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem 283 : 10415–10424.

21. CrooksGE, HonG, ChandoniaJM, BrennerSE (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14 : 1188–1190.

22. AuchtungJM, LeeCA, GarrisonKL, GrossmanAD (2007) Identification and characterization of the immunity repressor (ImmR) that controls the mobile genetic element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 64 : 1515–1528.

23. LeeCA, GrossmanAD (2007) Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and DNA relaxase required for conjugation of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 189 : 7254–7261.

24. BerkmenMB, LeeCA, LovedayEK, GrossmanAD (2010) Polar positioning of a conjugation protein from the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 192 : 38–45.

25. GoranovAI, KatzL, BreierAM, BurgeCB, GrossmanAD (2005) A transcriptional response to replication status mediated by the conserved bacterial replication protein DnaA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 12932–12937.

26. IretonK, GrossmanAD (1994) A developmental checkpoint couples the initiation of sporulation to DNA replication in Bacillus subtilis. Embo J 13 : 1566–1573.

27. CheoDL, BaylesKW, YasbinRE (1991) Cloning and characterization of DNA damage-inducible promoter regions from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 173 : 1696–1703.

28. BurrusV, WaldorMK (2003) Control of SXT integration and excision. J Bacteriol 185 : 5045–5054.

29. ShimadaK, WeisbergRA, GottesmanME (1972) Prophage lambda at unusual chromosomal locations. I. Location of the secondary attachment sites and the properties of the lysogens. J Mol Biol 63 : 483–503.

30. SmitsWK, GrossmanAD (2010) The transcriptional regulator Rok binds A+T-rich DNA and is involved in repression of a mobile genetic element in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet 6: e1001207.

31. CelliJ, Trieu-CuotP (1998) Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol Microbiol 28 : 103–117.

32. GarrityDB, ZahlerSA (1994) Mutations in the gene for a tRNA that functions as a regulator of a transcriptional attenuator in Bacillus subtilis. Genetics 137 : 627–636.

33. HoSN, HuntHD, HortonRM, PullenJK, PeaseLR (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77 : 51–59.

34. Youngman P, Poth H, Green B, York K, Olmedo G, et al.. (1989) Methods for Genetic Manipulation, Cloning, and Functional Analysis of Sporulation Genes in Bacillus subtilis. In: Smith I, Slepecky RA, Setlow P, editors. Regulation of Procaryotic Development. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. pp. 65–87.

35. WachA (1996) PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast 12 : 259–265.

36. Miller JH (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. xvi, 466 p.

37. JaacksKJ, HealyJ, LosickR, GrossmanAD (1989) Identification and characterization of genes controlled by the sporulation-regulatory gene spo0H in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 171 : 4121–4129.

38. GlaserP, FrangeulL, BuchrieserC, RusniokC, AmendA, et al. (2001) Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294 : 849–852.

39. PeregoM, SpiegelmanGB, HochJA (1988) Structure of the gene for the transition state regulator, abrB: regulator synthesis is controlled by the spo0A sporulation gene in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 2 : 689–699.

40. VandeyarMA, ZahlerSA (1986) Chromosomal insertions of Tn917 in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 167 : 530–534.

41. SmithBT, GrossmanAD, WalkerGC (2001) Visualization of mismatch repair in bacterial cells. Mol Cell 8 : 1197–1206.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek Independent Evolution of Transcriptional Inactivation on Sex Chromosomes in Birds and MammalsČlánek The bHLH Subgroup IIId Factors Negatively Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Plant Defense and DevelopmentČlánek Reassembly of Nucleosomes at the Promoter Initiates Resilencing Following Decitabine ExposureČlánek Hepatocyte Growth Factor Signaling in Intrapancreatic Ductal Cells Drives Pancreatic Morphogenesis

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 7- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Souvislost haplotypu M2 genu pro annexin A5 s opakovanými reprodukčními ztrátami

- Příjem alkoholu a menstruační cyklus

- Doporučení pro diagnostiku a léčbu akutních jaterních porfyrií

- Doc. Miloš Kubánek: Nemocní se srdeční amyloidózou jsou často skryti a sledováni pod jinými diagnózami

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- An Solution for Crossover Formation

- Genome-Wide Association Mapping in Dogs Enables Identification of the Homeobox Gene, , as a Genetic Component of Neural Tube Defects in Humans

- Independent Evolution of Transcriptional Inactivation on Sex Chromosomes in Birds and Mammals

- Stepwise Activation of the ATR Signaling Pathway upon Increasing Replication Stress Impacts Fragile Site Integrity

- Genomic Analysis of Natural Selection and Phenotypic Variation in High-Altitude Mongolians

- Modification of tRNA by Elongator Is Essential for Efficient Translation of Stress mRNAs

- Role of CTCF Protein in Regulating Locus Transcription

- Gene Set Signature of Reversal Reaction Type I in Leprosy Patients

- Mapping of PARK2 and PACRG Overlapping Regulatory Region Reveals LD Structure and Functional Variants in Association with Leprosy in Unrelated Indian Population Groups

- Is Required for Formation of the Genital Ridge in Mice

- Monopolin Subunit Csm1 Associates with MIND Complex to Establish Monopolar Attachment of Sister Kinetochores at Meiosis I

- Recombination Dynamics of a Human Y-Chromosomal Palindrome: Rapid GC-Biased Gene Conversion, Multi-kilobase Conversion Tracts, and Rare Inversions

- Mechanisms of Protein Sequence Divergence and Incompatibility

- Histone Methyltransferase DOT1L Drives Recovery of Gene Expression after a Genotoxic Attack

- Female Behaviour Drives Expression and Evolution of Gustatory Receptors in Butterflies

- Combinatorial Regulation of Meiotic Holliday Junction Resolution in by HIM-6 (BLM) Helicase, SLX-4, and the SLX-1, MUS-81 and XPF-1 Nucleases

- The bHLH Subgroup IIId Factors Negatively Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Plant Defense and Development

- The Role of Interruptions in polyQ in the Pathology of SCA1

- Dietary Restriction Induced Longevity Is Mediated by Nuclear Receptor NHR-62 in

- Fine Time Course Expression Analysis Identifies Cascades of Activation and Repression and Maps a Putative Regulator of Mammalian Sex Determination

- Genome-scale Co-evolutionary Inference Identifies Functions and Clients of Bacterial Hsp90

- Oxidative Stress and Replication-Independent DNA Breakage Induced by Arsenic in

- A Moonlighting Enzyme Links Cell Size with Central Metabolism

- Budding Yeast Greatwall and Endosulfines Control Activity and Spatial Regulation of PP2A for Timely Mitotic Progression

- The Conserved Intronic Cleavage and Polyadenylation Site of CstF-77 Gene Imparts Control of 3′ End Processing Activity through Feedback Autoregulation and by U1 snRNP

- The BTB-zinc Finger Transcription Factor Abrupt Acts as an Epithelial Oncogene in through Maintaining a Progenitor-like Cell State

- The Cohesion Protein SOLO Associates with SMC1 and Is Required for Synapsis, Recombination, Homolog Bias and Cohesion and Pairing of Centromeres in Drosophila Meiosis

- The RNA-binding Proteins FMR1, Rasputin and Caprin Act Together with the UBA Protein Lingerer to Restrict Tissue Growth in

- Pattern Dynamics in Adaxial-Abaxial Specific Gene Expression Are Modulated by a Plastid Retrograde Signal during Leaf Development

- A Network of HMG-box Transcription Factors Regulates Sexual Cycle in the Fungus

- Bacterial Adaptation through Loss of Function

- ENU-induced Mutation in the DNA-binding Domain of KLF3 Reveals Important Roles for KLF3 in Cardiovascular Development and Function in Mice

- Interplay between Structure-Specific Endonucleases for Crossover Control during Meiosis

- FGF Signalling Regulates Chromatin Organisation during Neural Differentiation via Mechanisms that Can Be Uncoupled from Transcription

- The Arabidopsis RNA Binding Protein with K Homology Motifs, SHINY1, Interacts with the C-terminal Domain Phosphatase-like 1 (CPL1) to Repress Stress-Inducible Gene Expression

- Selective Pressures to Maintain Attachment Site Specificity of Integrative and Conjugative Elements

- The Conserved ADAMTS-like Protein Lonely heart Mediates Matrix Formation and Cardiac Tissue Integrity

- The cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase EGL-4 Regulates Nociceptive Behavioral Sensitivity

- RBM5 Is a Male Germ Cell Splicing Factor and Is Required for Spermatid Differentiation and Male Fertility

- Disease-Related Growth Factor and Embryonic Signaling Pathways Modulate an Enhancer of Expression at the 6q23.2 Coronary Heart Disease Locus

- Yeast Pol4 Promotes Tel1-Regulated Chromosomal Translocations