-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Genome-scale Analysis of FNR Reveals Complex Features of Transcription Factor Binding

FNR is a well-studied global regulator of anaerobiosis, which is widely conserved across bacteria. Despite the importance of FNR and anaerobiosis in microbial lifestyles, the factors that influence its function on a genome-wide scale are poorly understood. Here, we report a functional genomic analysis of FNR action. We find that FNR occupancy at many target sites is strongly influenced by nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) that restrict access to many FNR binding sites. At a genome-wide level, only a subset of predicted FNR binding sites were bound under anaerobic fermentative conditions and many appeared to be masked by the NAPs H-NS, IHF and Fis. Similar assays in cells lacking H-NS and its paralog StpA showed increased FNR occupancy at sites bound by H-NS in WT strains, indicating that large regions of the genome are not readily accessible for FNR binding. Genome accessibility may also explain our finding that genome-wide FNR occupancy did not correlate with the match to consensus at binding sites, suggesting that significant variation in ChIP signal was attributable to cross-linking or immunoprecipitation efficiency rather than differences in binding affinities for FNR sites. Correlation of FNR ChIP-seq peaks with transcriptomic data showed that less than half of the FNR-regulated operons could be attributed to direct FNR binding. Conversely, FNR bound some promoters without regulating expression presumably requiring changes in activity of condition-specific transcription factors. Such combinatorial regulation may allow Escherichia coli to respond rapidly to environmental changes and confer an ecological advantage in the anaerobic but nutrient-fluctuating environment of the mammalian gut.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 9(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003565

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003565Summary

FNR is a well-studied global regulator of anaerobiosis, which is widely conserved across bacteria. Despite the importance of FNR and anaerobiosis in microbial lifestyles, the factors that influence its function on a genome-wide scale are poorly understood. Here, we report a functional genomic analysis of FNR action. We find that FNR occupancy at many target sites is strongly influenced by nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) that restrict access to many FNR binding sites. At a genome-wide level, only a subset of predicted FNR binding sites were bound under anaerobic fermentative conditions and many appeared to be masked by the NAPs H-NS, IHF and Fis. Similar assays in cells lacking H-NS and its paralog StpA showed increased FNR occupancy at sites bound by H-NS in WT strains, indicating that large regions of the genome are not readily accessible for FNR binding. Genome accessibility may also explain our finding that genome-wide FNR occupancy did not correlate with the match to consensus at binding sites, suggesting that significant variation in ChIP signal was attributable to cross-linking or immunoprecipitation efficiency rather than differences in binding affinities for FNR sites. Correlation of FNR ChIP-seq peaks with transcriptomic data showed that less than half of the FNR-regulated operons could be attributed to direct FNR binding. Conversely, FNR bound some promoters without regulating expression presumably requiring changes in activity of condition-specific transcription factors. Such combinatorial regulation may allow Escherichia coli to respond rapidly to environmental changes and confer an ecological advantage in the anaerobic but nutrient-fluctuating environment of the mammalian gut.

Introduction

Regulation of transcription initiation by transcription factors (TFs) is a key step in controlling gene expression in all domains of life. Genome-wide studies are revealing important features of the complexity of transcription regulation in cells not always apparent from in vitro studies. In eukaryotes, both the inhibition of TF binding by chromatin structure and the combinatorial action of multiple TFs contribute to the genome-wide pattern of TF binding and function [1]–[5]. In contrast, our knowledge of transcriptional regulation by bacterial TFs stems largely from elegant in vitro experiments that have provided atomic resolution views of TF function [6]. Much less is known about how chromosome structure and combinatorial action affect bacterial TF binding and transcriptional regulation on a genome-wide scale [7]. Previous studies have suggested that, in contrast to the chromatin-restricted TF binding in eukaryotes, the Escherichia coli genome is permissive to TF binding because the occupancy pattern for some TFs correlates well with match to consensus sequence and consequent binding affinity [8]–[10]. Other studies suggest that nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs; for example H-NS, Hu, Fis, and IHF) organize the chromosome into discrete domains and structures that may affect transcriptional regulation [7], [11]–[13], but possible global effects of NAPs on TF-binding have not been systematically tested. To investigate the roles of TF action and chromosome structure in a prototypical bacterial regulon, we studied the regulon of the anaerobic TF FNR.

FNR is widely conserved throughout the bacterial domain, where it evolved to allow facultative anaerobes to adjust to O2 deprivation [14]. Under anaerobic conditions, E. coli FNR contains one [4Fe-4S] cluster per subunit, which promotes a conformation necessary for FNR dimerization, site-specific DNA binding, and transcription regulation [15], [16]. Genome-wide transcription profiling experiments [17]–[19] established that E. coli FNR controls expression of a large number of genes under anaerobic growth conditions, in particular those genes whose products function in anaerobic energy metabolism. However, corresponding studies to establish which promoters are directly or indirectly regulated by FNR under comparable growth conditions have yet to be reported.

Studies of the regulatory regions of a few FNR controlled promoters have provided key insights into the mechanism of transcriptional regulation by FNR and the characteristics of FNR binding sites [20], [21]. From these studies we know that FNR binding sites can have only a partial match to the consensus sequence of TTGATnnnnATCAA, and be located at variable positions within promoter regions, directing whether FNR has either a positive or negative affect on transcription. At FNR repressed promoters, FNR binding site locations range from upstream of the −35 hexamer (which binds region 4.2 of RNA polymerase σ70), to overlapping the transcription start site (TSS; +1). At most FNR activated promoters, the center of the binding site is ∼41.5 nt upstream of the TSS, placing FNR in position to interact with both the σ70 and α subunits of RNA polymerase (RNAP) [21], [22]. Very few promoters are known to have FNR binding sites centered at −61.5 or greater, a position dependent typically on interactions with only the α subunit of RNAP [21]. The predominance of FNR binding sites positioned at −41.5 nt may reflect a preference for a particular activation mechanism, but it also could reflect sample bias in the limited number of activated promoters that have been studied to date. Thus, current knowledge is insufficient to allow accurate prediction of FNR binding sites genome-wide.

Many FNR regulated promoters are controlled by multiple TFs (for example CRP, NarL, NarP, and NAPs [7], [20], [21]), which can have either positive or negative effects on FNR function depending on the promoter architecture. For example, the narG promoter is activated by FNR, IHF, and the nitrate-responsive regulator, NarL [23], [24]; in contrast, the dmsA promoter is activated by FNR, but repressed by NarL [25], [26]. At the nir promoter, NarL displaces IHF to overcome a repressive effect of IHF and Fis, and thereby enhances FNR-dependent transcription [27]. Thus, in the presence of the anaerobic electron acceptor nitrate, FNR function can be either enhanced or repressed by NarL depending on the organization of TF-binding sites within the promoter region. In this way, the requirement of additional TFs for combinatorial regulation of promoters bound by FNR resembles transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes [28]. Such complex regulatory patterns cannot currently be inferred simply by identifying the locations of TF binding sites or by the strength of the FNR binding site. Direct measure of occupancy at these sites by each TF and correlation with the resulting transcripts in different growth conditions is needed to understand how complex bacterial regulatory networks coordinate gene expression. As an important first step, Grainger et al. used chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray hybridization (ChIP-chip) to examine FNR occupancy using a FLAG-tagged FNR protein in E. coli cultures grown anaerobically in a rich medium [29]. Although many new FNR binding sites were identified, these data were not obtained from cells grown in the growth media used for reported transcriptomic experiments [17]–[19] and thus the datasets cannot readily be compared.

To systematically investigate FNR binding genome-wide, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray hybridization (ChIP-chip) and high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) for WT FNR from E. coli grown anaerobically in a glucose minimal medium (GMM). Computational and bioinformatic analyses were used to refine a FNR position weight matrix (PWM). The PWM was used to determine the relationship between ChIP-seq/ChIP-chip enrichment and match to the PWM, and to identify predicted FNR binding sites not detected by ChIP-seq. To examine the subset of high-quality predicted FNR binding sites that lacked a FNR ChIP-seq peak, we obtained and analyzed aerobic and/or anaerobic ChIP-chip data for NAPs H-NS and IHF along with analysis of previously published aerobic ChIP-seq data for the NAP Fis [30] to determine if NAP occupancy might prevent FNR binding. Further, the effect of H-NS on FNR occupancy was examined directly using ChIP-chip analysis of FNR as well as on O2 dependent changes in expression in the absence of H-NS and its paralog StpA. After identifying FNR binding sites genome-wide, we performed whole genome transcription profiling experiments using expression microarrays and high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to compare a WT and Δfnr strain grown in the same medium used for the DNA binding studies. The transcriptional impact of FNR binding genome-wide was investigated by correlating the occupancy data with the transcriptomic data to determine which binding events led to changes in transcription, to identify the direct and indirect regulons of FNR, and to define categories of FNR regulatory mechanisms. Finally, the aerobic and anaerobic ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq distributions of the σ70 and ß subunits of RNAP throughout the genome were analyzed to determine the role of O2 and FNR regulation on RNAP occupancy and transcription.

Results

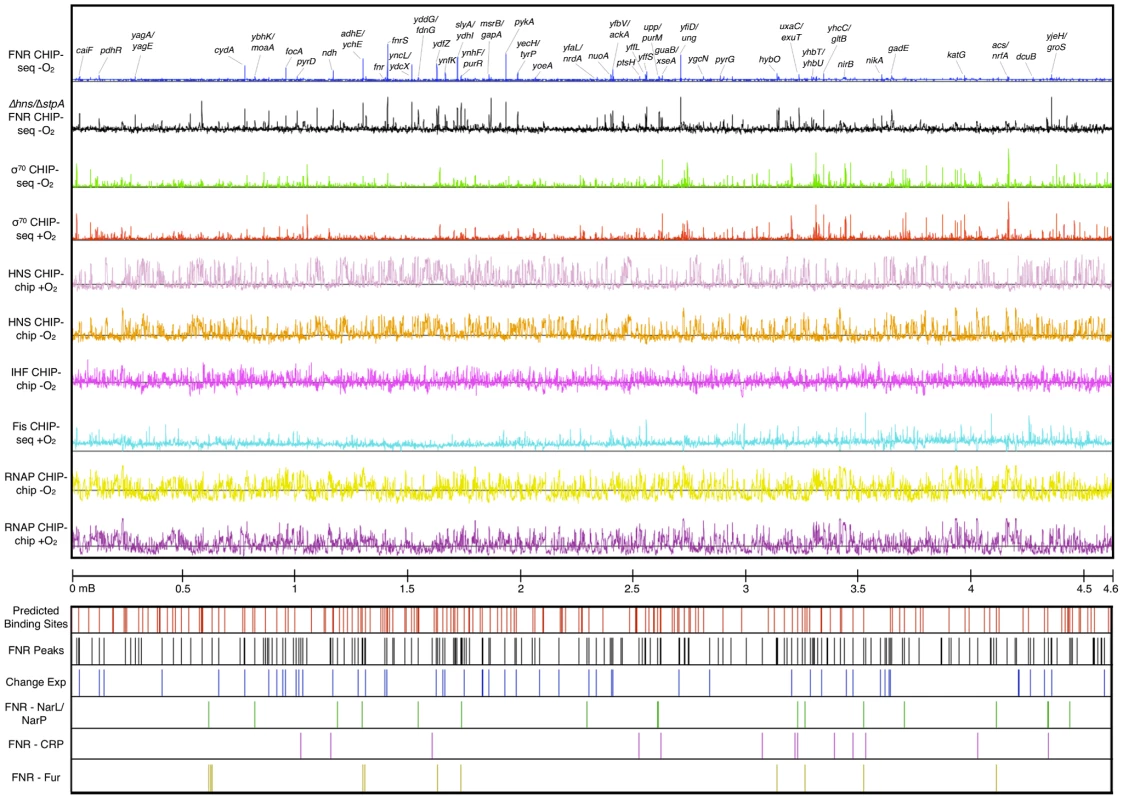

TF binding sites were mapped genome-wide in E. coli K-12 MG1655 using ChIP-chip and/or ChIP-seq for FNR, σ70 and ß subunits of RNAP, H-NS, and IHF under aerobic or anaerobic growth conditions, as indicated (Figure 1). In addition, we analyzed a publically available Fis data set collected under aerobic conditions [30]. The ChIP-chip distribution of the ß subunit of RNAP suggested widespread transcription under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, as expected, whereas the O2-dependent changes in ß occupancy indicated those genes that are differentially regulated by O2. Further, binding, and thus transcription, by the σ70 housekeeping form of E. coli RNAP was observed throughout the chromosome; peak finding algorithms identified a large number of anaerobic σ70 ChIP-seq peaks (2,106) and aerobic σ70 ChIP-seq peaks (2,446) (Table S1). About 700 of the σ70 peaks showed statistically significant O2-dependent changes in occupancy (Table S2). The O2-dependent differences in RNAP occupancy suggest extensive transcriptional reprogramming in response to changes in O2, providing an excellent model system for examining genome-scale changes in transcription.

Fig. 1. ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip data used in this study.

The tracks are (from top): FNR ChIP-seq −O2 (blue) with peaks upstream of a subset of genes labeled, FNR ChIP-chip in Δhns/ΔstpA −O2 (black), σ70 subunit of RNAP ChIP-seq −O2 (green), σ70 subunit of RNAP ChIP-seq +O2 (red), H-NS CHIP-chip +O2 (light purple), H-NS ChIP-chip −O2 (orange), IHF ChIP-chip −O2 (purple), Fis ChIP-seq +O2 [30] (aqua), β subunit of RNAP −O2 (yellow), β subunit of RNAP +O2 (dark purple), and genomic coordinates. Locations of FNR binding sites are also shown: predicted FNR binding sites (red lines), FNR ChIP-seq peaks (black lines), FNR peaks upstream of operons showing a FNR-dependent change in expression (blue lines), FNR peaks co-activated by NarL/NarP (green lines), FNR peaks co-activated by CRP (purple lines), and FNR peaks repressed by Fur (yellow lines). Comparison of the profiles of other DNA binding proteins indicated that the number of binding sites for NAPs genome-wide was much greater than for the TF FNR. ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip analyses identified 207 FNR peaks, 722 anaerobic H-NS enriched regions, 782 aerobic H-NS enriched regions, 1,020 anaerobic IHF enriched regions (Tables S3, S4, and S5) and published analysis of Fis identified 1,464 aerobic enriched regions [30]. The unbiased distribution of H-NS and IHF throughout the chromosome supports previous genome-wide studies of these NAPs [30]–[33]. H-NS is known to form filaments that cover multiple kb of DNA [7], [12], [13], [30], [34], [35] and we observed that half of the identified aerobic (390) and anaerobic (356) H-NS enriched regions were over 1 kb in length, referred to as extended H-NS binding regions (Table S3). Comparison of the aerobic and anaerobic H-NS binding distributions suggests H-NS occupancy is not greatly affected by O2 (Figure 1). For FNR, the number of high-confidence ChIP peaks (207) identified (Table S5) was just a few fold lower than the number of genes found to show FNR-dependent changes in expression (between 300–700) [17]–[19]. These binding site data were used to determine features of FNR binding genome-wide.

ChIP peak height did not correlate with similarity to the FNR consensus sequence

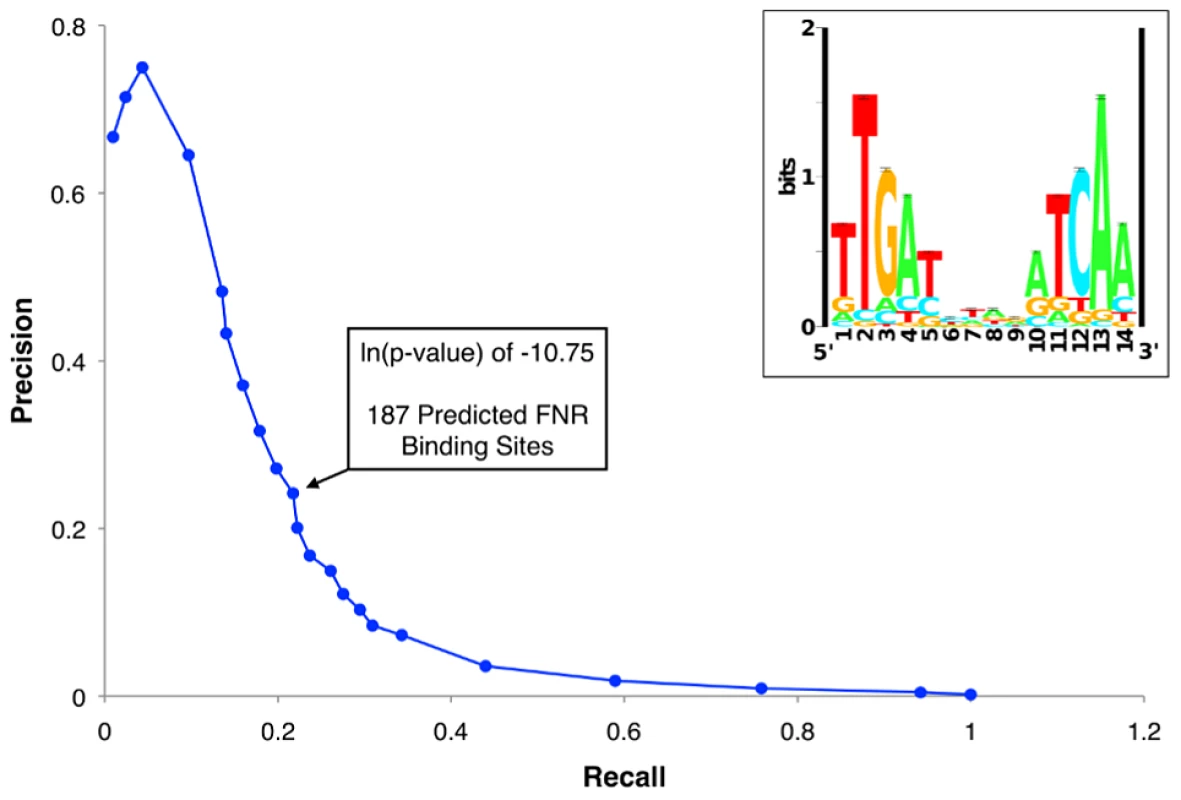

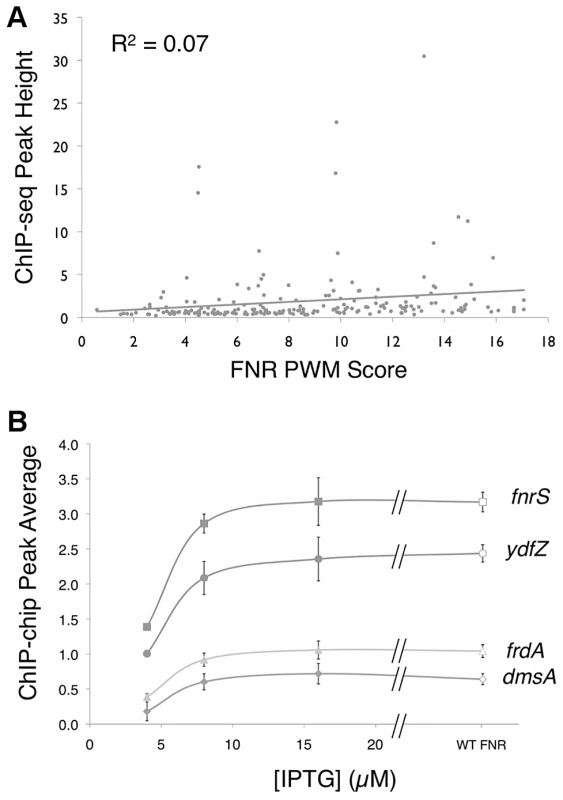

A small number of FNR peaks showed a large degree of variation in peak height across the genome. Previous studies of the repressor LexA reported that ChIP-chip peak height correlated with the match to the consensus sequence [10], suggesting that differences in site occupancy may reflect relative binding affinities to individual sites. Because FNR is a global regulator with a more degenerate binding site than LexA, we tested whether we could use this parameter to gain additional information about FNR binding-site preferences. A PWM (Figure 2 Inset) was constructed from an alignment of sequences from the ChIP-seq peaks and the scores representing the match to the PWM were determined with the algorithm PatSer (Table S5) [36]. In contrast to the studies of LexA [10], we found a poor correlation between the height of the FNR ChIP-seq peak and the match to the FNR PWM for the site predicted within each peak (Figure 3A). The same lack of correlation was also observed with FNR ChIP-chip data, indicating that this was not specific to the detection method. Additionally, there was a lack of correlation between FNR peak height and the number of known FNR binding sites. Furthermore, the majority of the FNR ChIP-seq or ChIP-chip peaks had similar heights, regardless of the score of the FNR motif present (Figure 3A).

Fig. 2. Precision-recall curve used to determine the prediction threshold of FNR binding sites and updated FNR PWM.

The precision-recall curve used to determine the optimal threshold for predicting high quality FNR binding sites throughout the genome. The precision and recall values were determined for many ln(p-value) thresholds using the PatSer algorithm and the optimal value is identified by the arrow. The inset shows the FNR position weight matrix (PWM) constructed from the FNR ChIP-seq peak sequences. The height (y-axis) of the letters represents the degree of conservation at that position within the aligned sequence set (in bits), with perfect conservation being 2 bits. The x-axis shows the position of each base (1–14) starting at the 5′ end of the motif. Fig. 3. ChIP peak height correlated with PWM score and over a range of FNR levels.

A)Correlation between FNR ChIP-seq peak height (read count at the summit of the peak) and the degree of agreement to the FNR PWM at each peak (as scored by PatSer [36], with higher values indicating a better match to the FNR PWM). The line is the best-fit between peak height and PWM score. B) Comparison of the average ChIP-chip peak height for FNR in WT cultures (open symbols) (∼2.5 µM FNR) and PK8263 (Ptac::fnr) cultures (closed symbols) at three [IPTG] concentrations: 4 µM IPTG (∼450 nM FNR), 8 µM IPTG (∼700 nM FNR), 16 µM IPTG (∼1.9 µM FNR). [FNR] determined by quantitative Western blot. Shown are four representative examples from the 39 regions examined (Figure S1). A t-test shows a statistically significant difference in peak average at all genes between 4 µM IPTG and 8 µM IPTG. One explanation for this latter result is that most FNR binding sites were saturated for binding in vivo. To examine this possibility directly, we performed ChIP-chip experiments over a range of cellular FNR dimer concentrations below the normal anaerobic cellular level of ∼2.5 µM [37], controlled by varying IPTG levels in a strain with fnr fused to an IPTG-inducible promoter. Peak areas for 35 selected FNR sites, representing a distribution of peak heights, were quantified for several cellular FNR dimer concentrations (∼0.45, ∼0.7, ∼1.9, and ∼2.5 µM). These plots showed a typical binding saturation curve for both novel and previously identified FNR binding sites, and revealed that all sites examined were saturated for binding at the normal cellular FNR dimer level of ∼2.5 µM (Figure 3B, Figure S1). However, because the broad distribution of peak heights between different sites was still observed, despite the fact that the sites were maximally occupied, we concluded that variation in peak height was not related to strength of FNR binding (Figure 3, Figure S1). As a control, we tested four FNR peaks that were determined to be non-specific due to enrichment in a Δfnr control ChIP-chip experiment and these peaks showed no change in peak height when FNR levels were varied (Figure S1). Thus, we conclude that differences in peak height in the ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip experiments for FNR were most likely due to differences in cross-linking efficiency or immunoprecipitation at particular genomic locations and not to differences in FNR binding affinity.

Cross-linking of FNR to a subset of genomic locations may be inhibited by other proteins

A well-known challenge in genomic studies is the use of computational tools to accurately predict DNA binding sites, particularly for global regulators like FNR that have degenerate binding sites. To investigate the usefulness of the PWM generated from our set of ChIP binding sites for predicting FNR sites genome-wide, we initially used a PatSer [36] threshold low enough that a FNR motif was identified in each FNR ChIP-seq peak. However, this threshold resulted in >10,000 possible genomic FNR binding sites. In contrast, if we used a precision-recall (PR) curve [38] to determine the optimal threshold to predict FNR binding sites (ln(p-value) of −10.75), then we obtained a more reasonable number (187) of predicted FNR binding sites (Figure 2, Table S6). Surprisingly, fewer than half of these sites (63 of 187) corresponded with a FNR ChIP-seq peak (Table S6), despite the fact that some predicted sites without a corresponding ChIP-seq peak had higher quality PatSer scores than those with a ChIP-seq peak. Although it is possible that some of the predicted sites without a ChIP-seq peak contain flanking sequence elements that disfavor FNR binding, we considered the possibility that many are functional sites but either FNR binding was masked by other DNA binding proteins or FNR cross-linking failed for other reasons.

NAPs are known to affect the binding of some TFs in E. coli [7], [12]. To ask if the NAPs H-NS, IHF, or Fis might occlude the 124 predicted FNR binding sites lacking a FNR ChIP-seq peak, we analyzed ChIP-chip data for H-NS and IHF, obtained from the same growth conditions, and publicly available ChIP-seq data for Fis [30]. Nearly all of these FNR sites (111 of 124 sites; ∼90%; silent FNR sites) were enriched in IHF, H-NS, or Fis, consistent with the idea that these NAPs occupy the silent FNR sites and thereby block FNR binding (Table S6, Figure S2). Similar occupancy was observed when the 124 predicted FNR sites were compared with H-NS and IHF enrichment from published ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq data performed under different growth conditions [30], [31], [33]. In comparison, only ∼20% (14 of 63 sites) of the FNR sites that coincided with a FNR ChIP-seq peak were enriched in a NAP ChIP signal, significantly less than NAP occupancy at FNR sites lacking a peak (p-value<0.05). In contrast, we found ∼50% of the previously identified LexA binding sites [10] were co-occupied with H-NS. We conclude that the NAPs H-NS, IHF, or Fis likely prevent FNR binding at some sites by occlusion.

We also examined whether the silent FNR sites are preferentially occluded by the extended H-NS binding regions. The extended binding regions of H-NS (>1 kb) likely represent H-NS filaments that are known to cover multiple kb of DNA and silence transcription [7], [12], [13], [30], [34]. Consistent with this notion, our results showed that the extended H-NS binding regions were negatively correlated with RNAP (ß) ChIP-chip occupancy and this silencing occurred in both the presence and absence of O2 (p-value<0.05) (Figure S3). In contrast, shorter H-NS enriched regions (<1 kb) were both positively and negatively correlated with RNAP ChIP-chip occupancy under aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions. The 46 silent FNR sites bound by H-NS were more likely to be occupied by extended H-NS binding regions (42 sites) than by short H-NS binding regions (4 sites) (p-value<0.05; example in Figure S3C), suggesting that extended H-NS binding regions may inhibit FNR binding at silent FNR sites.

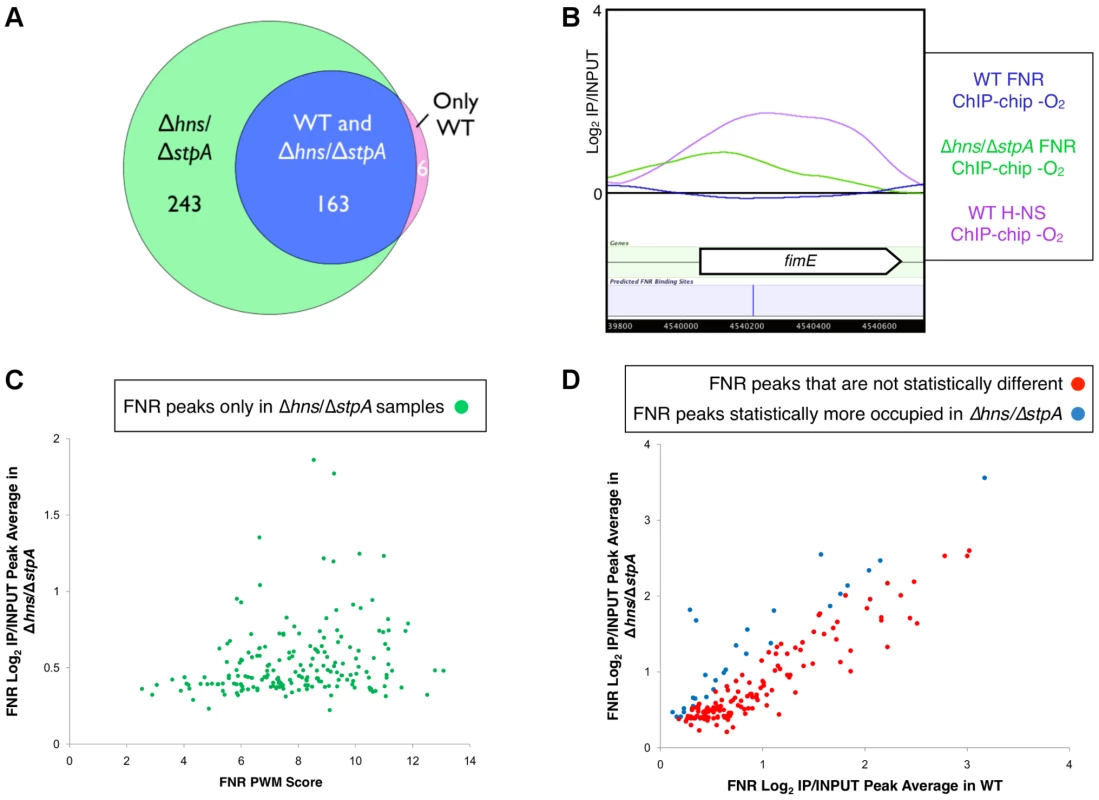

To investigate the impact of H-NS binding on FNR occupancy, we characterized FNR ChIP-chip peaks in a strain deleted for both hns and stpA; stpA encodes a H-NS paralog that partially compensates for H-NS in a Δhns mutant [39], [40]. Many new FNR peaks (196) appeared in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain (Figure 1, Figure 4A–C, Table S7), and a large fraction (81%; 158 FNR peaks) of these new peaks corresponded to H-NS binding regions in the WT strains, indicating that FNR binding was unmasked in the absence of H-NS and StpA. The distribution of the FNR PWM scores of the FNR sites found within the FNR ChIP-chip peaks unmasked by the absence of H-NS and StpA was similar to that found in the WT strain (Figure 4C, Tables S6 and S7). The majority (78 of 99) of silent FNR sites lacking FNR peaks in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain were enriched for IHF and/or Fis, suggesting that these NAPs still occluded FNR binding in the absence of H-NS and StpA (Table S6). Taken together, these results establish that removal of H-NS and StpA allowed FNR to bind to sites covered by H-NS in WT strains.

Fig. 4. Identification of FNR occupancy in a Δhns/ΔstpA strain compared to WT.

A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of FNR peaks identified only in the WT strain (purple), in both the WT and the Δhns/ΔstpA strains (blue) or only in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain (green). B) Example of a high-quality predicted FNR binding site (blue line) within fimE that showed no FNR binding in the WT strain (blue trace), but did show enrichment of H-NS in the WT strain (purple trace). A FNR ChIP-chip peak was identified in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain (green trace) at the location of the predicted FNR binding site. C) The 193 FNR peaks found only in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain with a statistical increase in FNR occupancy in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain compared to the WT strain (p-value<0.05). Correlation of ChIP-chip peak average (log2(IP/INPUT) average) and the corresponding FNR PWM score (determined by PatSer [36]). D) Correlation of ChIP-chip peak averages (log2(IP/INPUT) average) for FNR ChIP-chip peaks found in both WT and Δhns/ΔstpA strains. Shown are peaks with no statistical difference in occupancy (red points) and those peaks that showed a statistical increase in FNR occupancy (blue points) in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain compared to the WT strain (p-value<0.05). Nearly all FNR peaks found in the WT strain were retained in the Δhns/ΔstpA mutant (163 of 169 peaks; Figure 4A, Table S7), but a small proportion (∼15%) showed a significant increase in peak average (average log2(IP/INPUT) value of the binding region) in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain (Figure 4D). The majority of these FNR peaks with increased peak averages were also bound by H-NS in the WT strain, suggesting that removing H-NS allowed for increased cross-linking or immunoprecipitation of FNR at these loci likely due to changes in chromosomal structure in the absence of H-NS and StpA [35]. In contrast, removing H-NS did not affect FNR occupancy or cross-linking at locations lacking H-NS ChIP signal in WT strains. We conclude that H-NS reduces or blocks FNR binding at many locations in vivo.

Operons in the FNR regulon were organized into seven regulatory categories

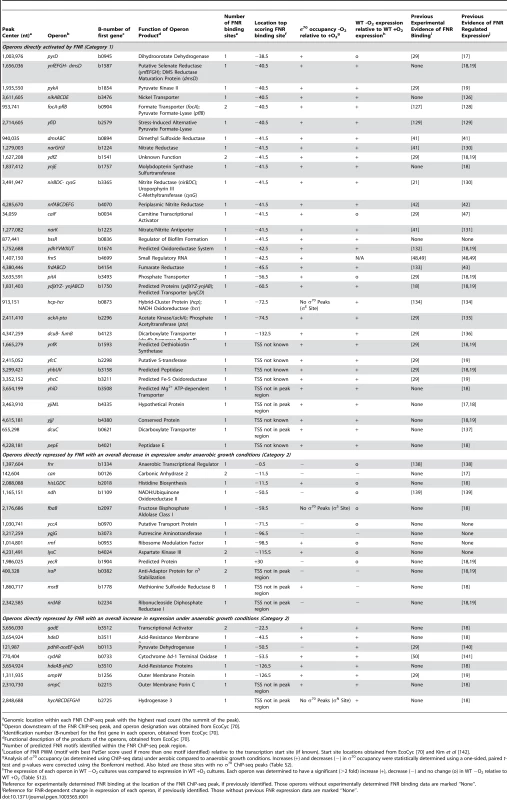

To determine which FNR binding events from the WT strain caused a change in gene expression, the FNR occupancy data were correlated with the 122 operons differentially expressed (DE) by FNR (Table S8). Surprisingly, less than a half of the 122 operons were correlated with a FNR ChIP-seq peak while less than a fourth of the 207 FNR ChIP-seq peaks were correlated with a FNR-dependent change in expression (Figure S4). To address this unexpected result, we systematically analyzed the regulation of all of these operons by incorporating published data and classified the operons into seven regulatory categories (Figure 5). Category 1 (Table 1) contained operons that were directly activated by FNR because they showed a FNR-dependent increase in anaerobic transcript levels and a FNR ChIP-seq peak within 500 nt of the translation start site of the first gene of an operon. Category 2 (Table 1) contained operons that were directly repressed by FNR (showed a FNR-dependent decrease in expression and had a FNR ChIP-seq peak). Categories 3–5 contained a surprisingly large number of operons (156) with a FNR ChIP-seq peak within 500 nt of the translation start site of the first gene of an operon but no FNR-dependent change in expression. Previously published studies (23 operons) and our additional collation of other relevant TF-binding sites (52 operons) suggest that at least half (75) of these sites may be directly regulated by FNR under alternative growth conditions (Table S9). For example, Category 3 (Tables 2 and 3) contained operons known or proposed to be co-regulated by FNR and another TF under growth conditions not used in our study. Category 4 (Table 4) contained operons known to be repressed by another TF under our growth conditions. Category 5 (Table S9) contained operons with other potential regulatory mechanisms. Category 6 (Table 5, Table S10) contained operons that were indirectly regulated by FNR because no FNR ChIP-seq peak was found within 500 nt of the translation start site despite showing a FNR-dependent change in expression. Finally, Category 7 (Table S11) contained operons with a FNR peak identified only in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain, which also showed potential FNR regulation in the absence of H-NS and StpA.

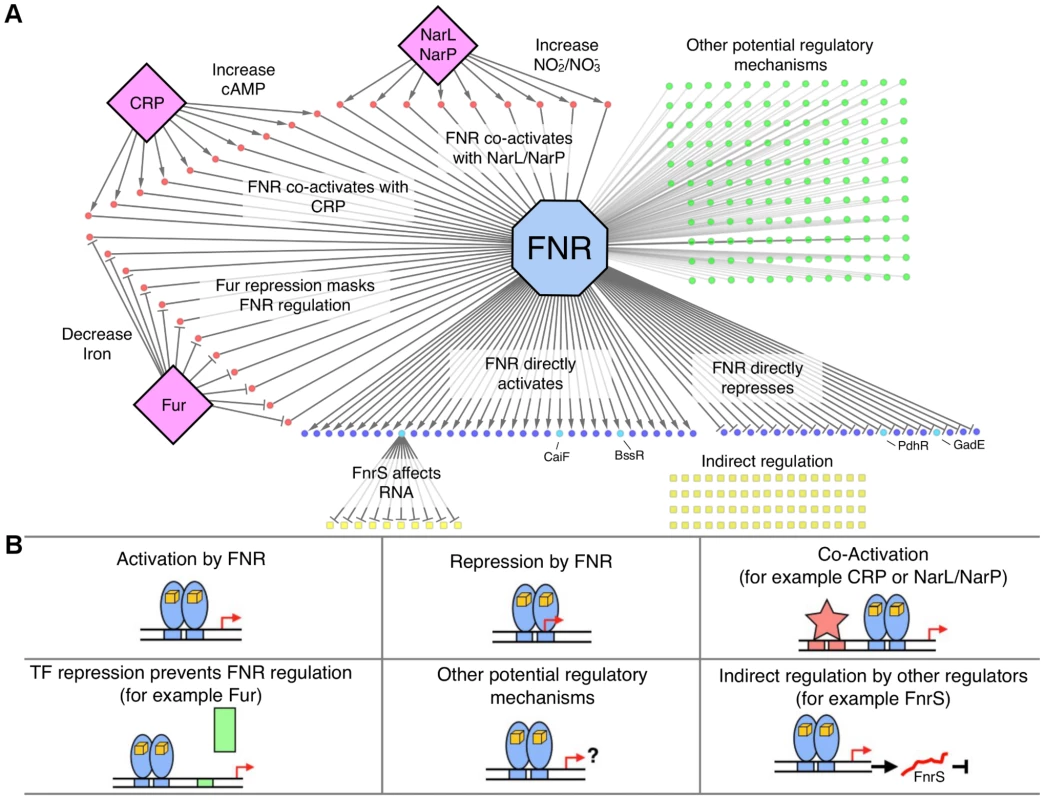

Fig. 5. The FNR transcriptional network and categories of FNR regulation.

A) Graphical representation of the FNR transcriptional network. FNR is shown in the blue octagon, while other TFs (CRP, Fur, NarL) are shown as purple diamonds. Circles represent operons with an upstream FNR ChIP-seq peak, while squares represent operons indirectly regulated by FNR. Dark blue circles are operons directly dependent on FNR for expression, with the lighter blue circles representing FnrS other TFs (CaiF, BssR, PdhR, GadE) that potentially control the indirect regulon, shown by yellow squares. Red circles are operons known or predicted to be co-regulated by FNR and other TFs, while green circles have other potential regulatory mechanisms with FNR. B) Each box represents different categories of FNR regulation identified in this study. Categories 1 and 2 (upper left and middle boxes) show direct activation and repression of operons by FNR (blue ovals). Category 3 (upper right box) show co-activation by other TFs (red star; e.g. CRP, NarL, NarP) and Category 4 (lower left box) shows TF repression that prevents FNR regulation (green rectangle; e.g. Fur). Category 5 (lower middle box) represents operons with other possible regulatory mechanisms with FNR and Category 6 (lower right box) shows the subset of the indirect regulon affected by other TFs and, for example, by the small, regulatory RNA FnrS (red line). Tab. 1. Operons with an upstream FNR ChIP-seq peak and a FNR-dependent change in expression under GMM.

Genomic location within each FNR ChIP-seq peak with the highest read count (the summit of the peak). Tab. 2. Operons associated with a FNR ChIP-seq peak and lacking a FNR-dependent change in expression in GMM but are activated by FNR in the presence of NO3−, NO2−, NarL or NarP (Category 3) according to Constantinidou et al. [19]. ![Operons associated with a FNR ChIP-seq peak and lacking a FNR-dependent change in expression in GMM but are activated by FNR in the presence of NO<sub>3</sub><sup>−</sup>, NO<sub>2</sub><sup>−</sup>, NarL or NarP (Category 3) according to Constantinidou <i>et al.</i> <em class="ref">[19]</em>.](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/e9543ec37fc0b8d12247c728d8a37b2d.png)

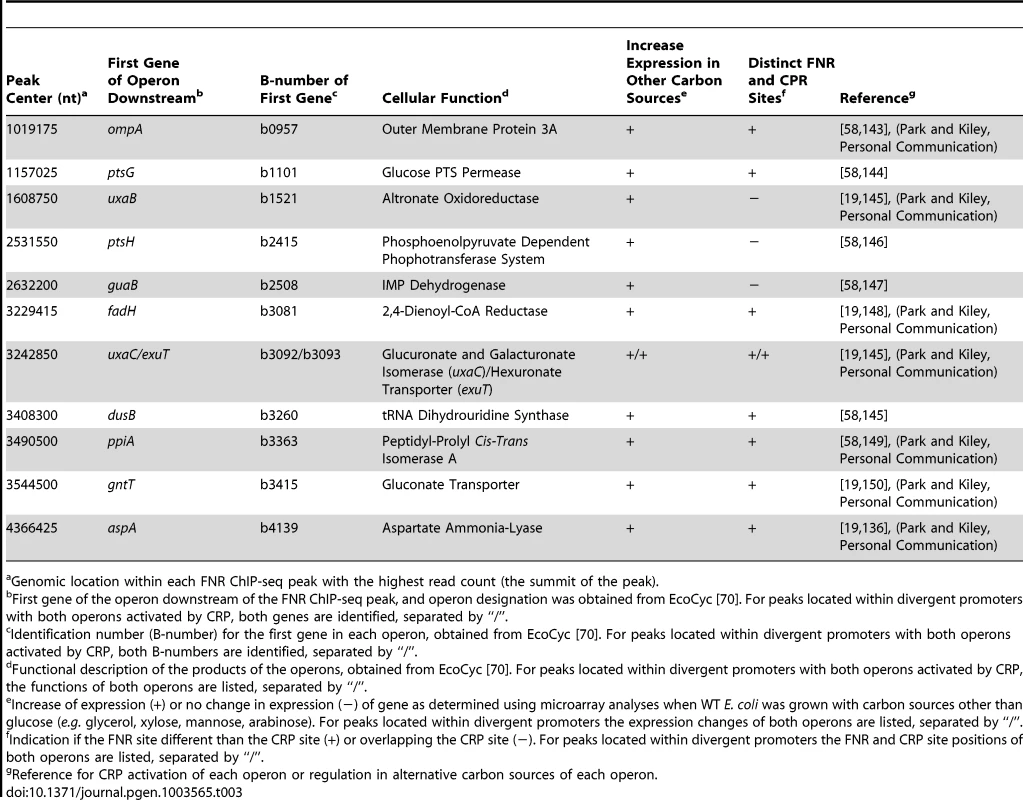

Genomic location within each FNR ChIP-seq peak with the highest read count (the summit of the peak). Tab. 3. Operons associated with a FNR ChIP-seq peak and lacking a FNR-dependent change in expression in GMM but are potentially co-activated by CRP and FNR (Category 3).

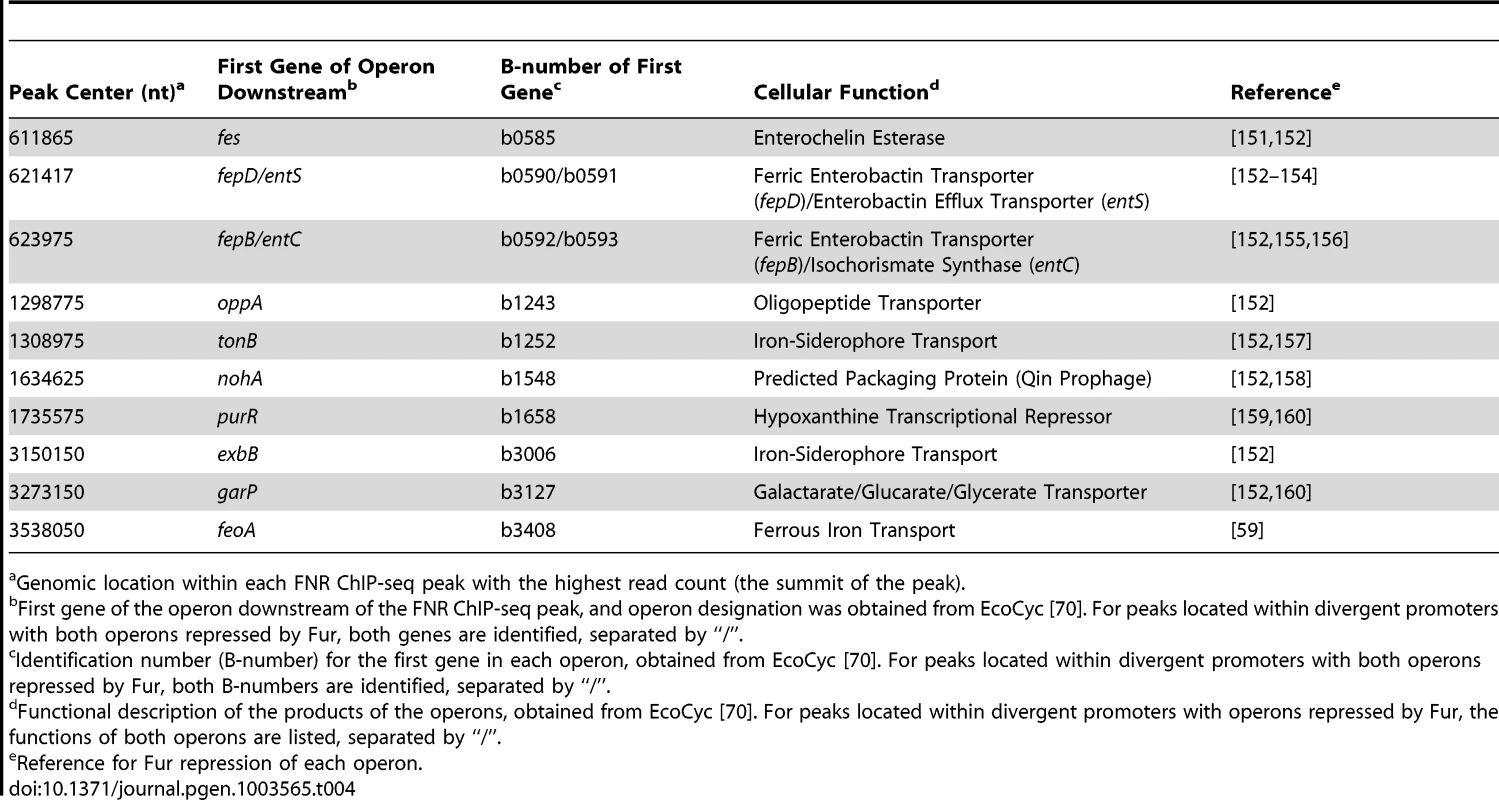

Genomic location within each FNR ChIP-seq peak with the highest read count (the summit of the peak). Tab. 4. Operons associated with a FNR ChIP-seq peak and lacking a FNR-dependent change in expression in GMM but are repressed by Fur (Category 4).

Genomic location within each FNR ChIP-seq peak with the highest read count (the summit of the peak). Tab. 5. Operons lacking a FNR ChIP-seq peak but with a FNR-dependent change in expression in GMM that are known to be regulated through the action of the small regulatory RNA FnrS (Category 6).

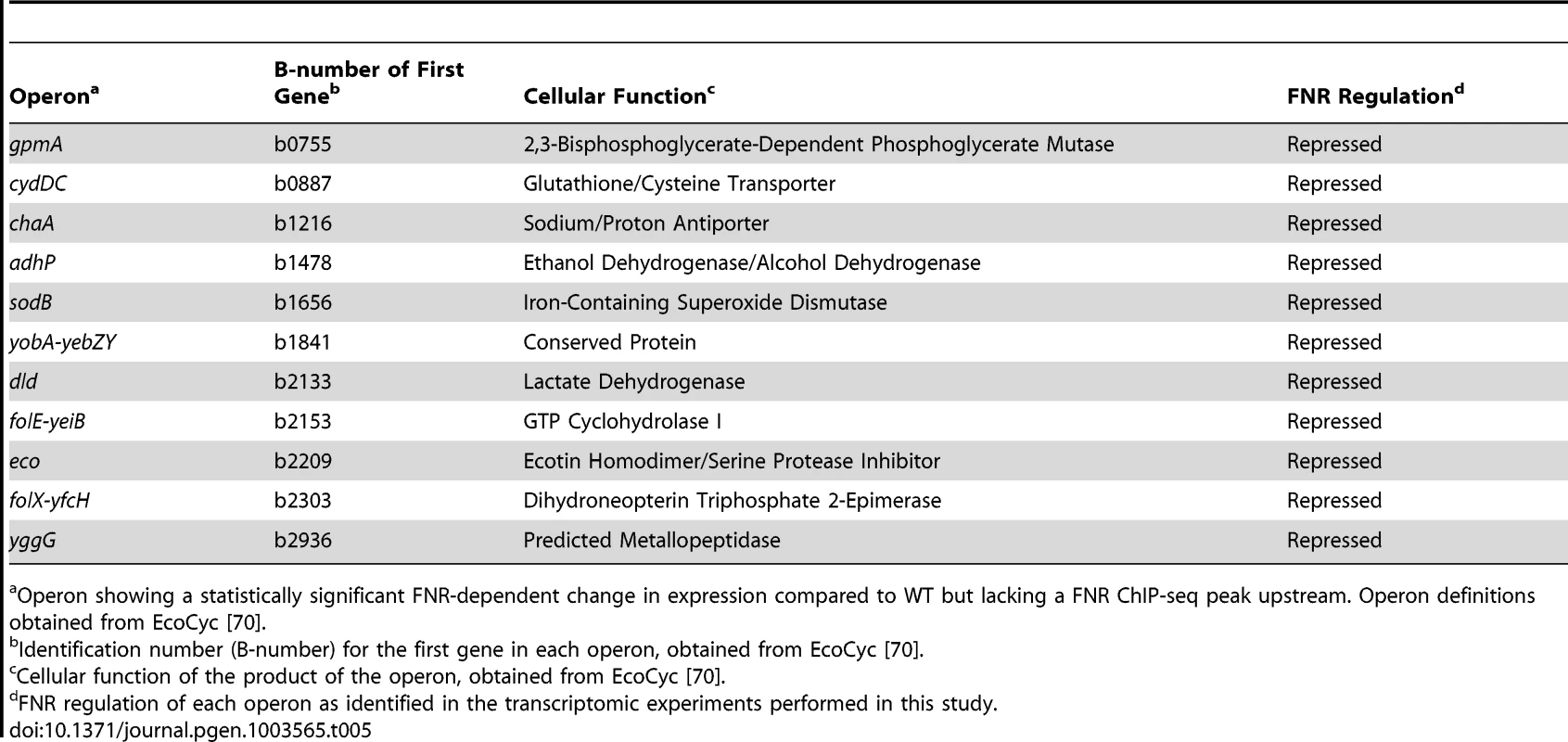

Operon showing a statistically significant FNR-dependent change in expression compared to WT but lacking a FNR ChIP-seq peak upstream. Operon definitions obtained from EcoCyc [70]. Category 1 - Direct activation by FNR

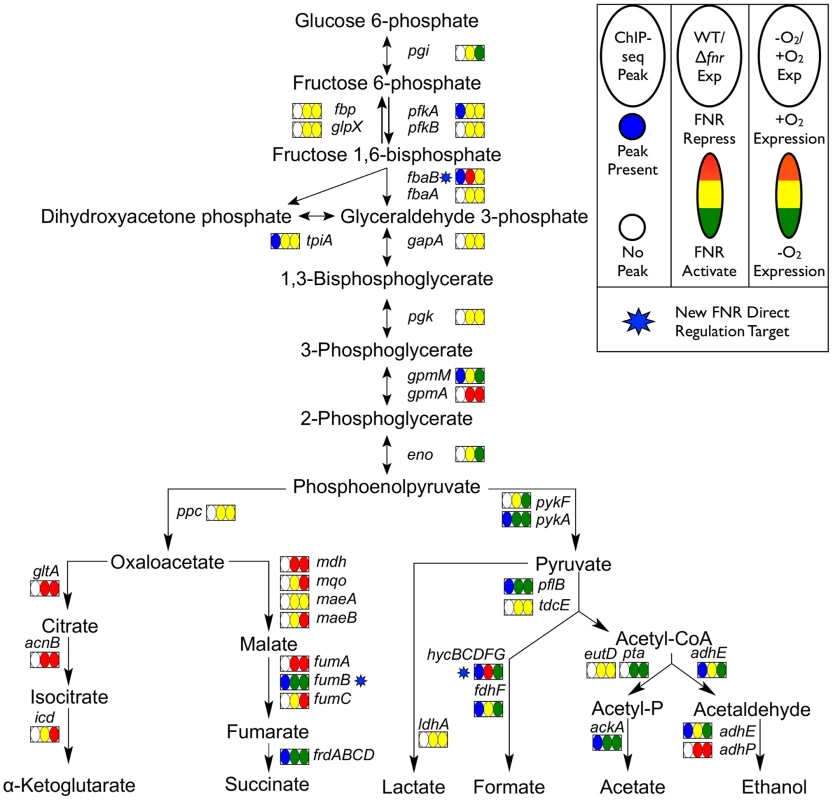

The 32 operons directly activated by FNR (Table 1) contain some of the best-studied FNR regulated operons. In addition to operons associated with anaerobic respiration (dmsABC, frdABCD, nrfABCDEFG, narGHJI) [41]–[43], this category included glycolytic (pykA) and fermentative enzymes (pflB and ackA), which would be expected to promote mixed acid fermentation of glucose to ethanol, acetate, formate and succinate in the absence of an added electron acceptor (Figure 6), the conditions used in this study. As expected, we also found that these promoters showed an increase in σ70 occupancy, as illustrated by representative FNR and σ70 data for FNR activation of dmsABC (Figure 7), providing a proof-of-principle for our approach. While expression of many operons in this category was known to be FNR regulated, only about half had been shown to directly bind FNR (Table 1).

Fig. 6. Glycolysis and mixed acid fermentation pathway overlaid with FNR and O2 regulation.

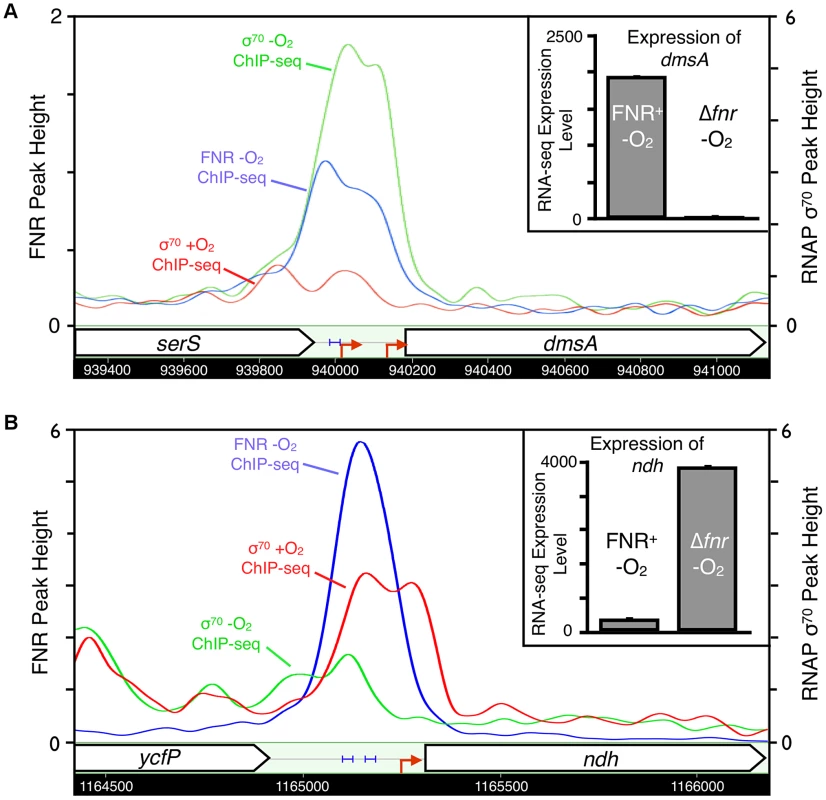

Pathway map showing the glycolysis and mixed acid fermentation pathway overlaid with FNR ChIP-seq peak occupancy and expression changes [124]. Reactions are represented by arrows connecting metabolites and each operon is represented by a box with three ovals. The first oval of each box indicates the presence (blue) or absence (white) of a FNR ChIP-seq peak upstream of that operon. The color of the second oval indicates the impact of FNR on the expression of the operon (red is FNR repression, while green is FNR activation). The color of the third oval indicates the expression under WT aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions (red is WT aerobic expression, while green is WT anaerobic expression). The blue stars indicate newly identified direct targets of FNR regulation within this pathway. Fig. 7. Representative examples of FNR directly activated and repressed promoters.

Representative examples of FNR directly activated (dmsA, panel A) and repressed (ndh, panel B) promoters confirmed in our study. Shown are the ChIP-seq data traces of anaerobic FNR (blue), anaerobic σ70 (green) and aerobic σ70 (red). ChIP-seq peak heights are represented on the y-axis (log2 kernel density [115]). The chromosomal location is shown on the x-axis with genes represented by arrows pointing in the direction of transcription. Known promoters are represented as red arrows and previously identified FNR binding sites are shown by blue brackets. The inset shows the linear expression levels for each gene from the RNA-seq experiments comparing FNR+ and Δfnr -O2 expression. Linear tag density [125] for each gene is shown on the y-axis. FNR also directly activated operons with functions that illustrate the broader role of FNR in anaerobic metabolism: pepE, a peptidase, suggesting peptide degradation in E. coli similar to that observed in Salmonella [44]; ynjE, an enzyme involved in biosynthesis of molybdopterin, a cofactor used by anaerobic respiratory enzymes [45]; pyrD, a dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in pyrimidine biosynthesis [46]; and ynfK, a predicted dethiobiotin synthetase and paralog of BioD of the biotin synthesis pathway. The activation of the biofilm TF bssR by FNR suggests a link between biofilm formation and anaerobiosis (Table 1). FNR directly activated the carnitine-sensing TF CaiF, confirming a link between FNR and carnitine metabolism [29], [47]. In addition, the FNR-enriched region found upstream of fnrS supports FNR direct transcription activation of this small regulatory RNA [48], [49], although the fnrS sRNA was not represented in our gene expression arrays and was too small to be detected by our RNA-seq protocol (Table 1).

To determine the position of FNR binding sites relative to the TSS, we used the FNR PWM (Figure 2 Inset) to search the FNR enriched regions using a PatSer score threshold low enough to identify FNR sites from every ChIP peak [36]. A majority (89%) of the FNR ChIP-seq peaks in the FNR direct regulon contained one FNR binding site (Table 1). Of the 23 promoters directly activated by FNR with a known TSS, 19 FNR sites were centered at −41.5 (±4 nt), the known position of a Class II site, while one site was centered at −60.5 (Class I site) (Table 1), supporting previous results suggesting a bias toward FNR binding Class II sites in activated promoters.

Category 2 - Direct repression by FNR

Analysis of the 21 operons directly repressed by FNR revealed both simple and complex repression mechanisms (Table 1). The majority of the operons directly repressed by FNR showed expression patterns similar to that of ndh, encoding the aerobic NADH dehydrogenase II, which showed a FNR-dependent decrease in expression and decrease in σ70 occupancy under anaerobic growth conditions (Figure 7). These operons included nrdAB, the aerobic ribonucleotide reductase; hisLGDC, a subset of the histidine biosynthesis enzymes; fbaB, the class I fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase involved in gluconeogenesis; and can, the carbonic anhydrase. FNR also repressed iraP, which encodes the anti-adaptor protein that stabilizes σS, and rmf, which encodes the stationary phase inducible ribosome modulation factor.

In contrast, a subset of operons showed complex repression similar to cydAB, with an anaerobic dependent increase in expression despite the fact that anaerobic expression increased further in a strain lacking FNR, indicating partial repression (Table 1) [50]. Nearly all of these operons are also co-regulated by ArcA (Park and Kiley, Personal Communication) suggesting that, like cydAB, FNR and ArcA co-regulation could lead to maximal expression of these genes under microaerobic conditions [50]. These operons include hdeD, gadE and hdeAB-yhiD, involved in acid stress response, and ompC and ompW, encoding outer membrane proteins. The finding that strains lacking ompC, rmf, and rpoS show decreased viability compared to single or double mutants [51] suggests that these proteins may function in a common stress response, potentially necessary under microaerobic growth conditions. Interestingly, for the 16 promoters directly repressed by FNR with a known TSS, the FNR binding sites were broadly distributed, ranging from −125.5 to overlapping the +1 (Table 1). In sum, these results indicate the surprising finding that FNR directly represses a broad set of functions, including some stress responses, expanding the role of FNR beyond simply repressing genes associated with aerobic respiration.

Finally, comparison of the transcriptomic data to changes in σ70 holo-RNAP ChIP-seq occupancy under aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions revealed that nearly all FNR-regulated operons are expressed using σ70 RNAP. Increases or decreases in σ70 enrichment under anaerobic conditions correlated well, for the most part, with the expression changes for promoters activated or repressed by FNR, respectively, as well as expression changes in anaerobic and aerobic WT cultures (Table 1, Tables S2 and S12). Three operons, which lacked σ70 enrichment, have been shown to be dependent on σE (hcp-hcr) [52], σN (hycABCDEFGHI) [53] and σS (fbaB) [54], raising the possibility that alternative σ factors transcribe a subset of the FNR direct regulon.

Category 3 – Co-activation by another TF and FNR

Comparison of our FNR data with published regulatory data suggested that many FNR regulated operons were co-activated by TFs not active during growth in GMM, specifically NarL, NarP and CRP. For example, FNR-dependent transcription of napFDAGHBC, encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase, requires co-activation by the NO3−/NO2− sensing response regulator NarP [55]. Transcriptomic data [19] showed FNR and NarL or NarP dependent activation in the presence of NO3− and/or NO2− (Table 2) [19] for nine operons that we found associated with FNR ChIP-seq peaks but lacking a FNR-dependent change in expression in our transcriptomic experiments, suggesting co-activation by NarL or NarP when NO3− and/or NO2− is present.

Another possible co-activator of operons in this group is CRP, which is inactive under glucose fermentation conditions presumably because of decreased cAMP [56]. Although previous studies have shown that ansB is co-activated by FNR and CRP [57], we did not observe binding of FNR upstream of ansB in this study, potentially due to differences in growth conditions. Nevertheless, 12 operons within this group showed an increase in anaerobic expression in transcriptomic data obtained from WT strains grown with carbon sources other than glucose (e.g. glycerol, mannose, arabinose or xylose) compared to growth in glucose (Table 3) [19], [58] (Park and Kiley, Personal Communication). A majority (nine) contained distinct CRP and FNR binding sites, suggesting co-activation by FNR and CRP when glucose is absent and cAMP levels are increased (Table 3). Interestingly, for the other three of these operons, guaB, ptsH and uxaB, the identified FNR binding site overlapped the CRP binding site, suggesting potential competition between FNR and CRP for binding when both TFs are active (Table 3).

Category 4 – Repression by another TF prevents FNR regulation

We propose that FNR activation of ten operons is repressed by Fur under the iron replete conditions used here, similar to the known regulation of feoABC, encoding a ferrous iron uptake transporter [59]. In addition to feoABC, nine additional operons known to be bound by Fur had a FNR ChIP-seq peak but lacked a FNR-dependent change in expression, suggesting that Fur repression masked FNR regulation of these operons (Table 4).

Category 5 – Other potential regulatory mechanisms with FNR

Expression of several of the remaining operons associated with FNR ChIP-seq peaks are known to require other TFs but were not known to be co-regulated by FNR, potentially explaining the lack of FNR-dependent regulation under our growth conditions. A subset of these FNR-regulated operons may be co-regulated by OxyR (active under oxidative stress), CadC (active at low external pH) or PhoP (active in low Mg2+ concentration) (Table S9). In a recent SELEX study [60], three BasR binding sites were identified upstream of operons containing FNR peaks but without a FNR-dependent change in expression, suggesting BasR could possibly influence FNR regulation at these three promoters (Table S9).

In some cases, promoter architecture may mask FNR regulation. A small number of operons (12) contained multiple TSSs, raising the possibility that FNR may regulate transcription from a TSS that does not increase the total transcript levels to above the cutoff used in our analyses (Table S9). Alternative σ factors, active under other growth conditions, may also play a role in regulating transcription of a subset of these operons (Table S9). Taken together, we conclude that although FNR serves as a global signal for anaerobiosis, many operons likely require the combinatorial integration of TFs sensing other environmental signals for expression.

Category 6 – Indirect FNR regulation through hierarchical transcriptional regulator action

Surprisingly, a large number of operons (70) were differentially expressed by FNR but were not associated with a FNR ChIP-seq peak, suggesting they are regulated by FNR indirectly (Category 6, Table S10). To determine whether any of these operons had a FNR site upstream that was missed by ChIP-seq, sequences 500 nt upstream of these operons were searched using the FNR PWM and the algorithm PatSer with the PR curve determined threshold (Figure 2) [36]. Only one operon, hmp, contained a predicted FNR-binding site and previous data also supported FNR binding to hmp [61]. Thus, 69 operons are indirectly regulated by FNR. The indirect regulation by FNR could be easily explained for 11 operons targeted by the small RNA FnrS, which is directly activated by FNR [48], [49]. These RNAs increased in the FNR− strain because of the lower FnrS levels (Table 5) [48], [49].

Category 7 – FNR regulation in the absence of H-NS and StpA

To determine whether FNR binding to sites unmasked by the absence of H-NS and StpA caused a change in expression, we assayed if any of the corresponding genes were differentially expressed by O2 only in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain. Of the 158 new FNR peaks unmasked in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain, 18 genes showed an anaerobic increase in expression (Table S11), and consistent with this, many of the promoters contained a FNR binding site at a position associated with activation (e.g. near −41.5). For example, hemolysin E (hlyE), in agreement with previous results [62], and the anaerobic NAP Dan (ttdR) [63] showed increased expression under anaerobic conditions only. This suggests a possible role of Dan in the absence of H-NS and StpA. Only two genes showed a decrease in expression in the absence of H-NS and StpA (yncD and feaR) under only anaerobic growth conditions. However, the expression of the vast majority of genes having FNR bound at unmasked sites resulted in changes under both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions, indicating that changes in nucleoid structure that occur in the absence of H-NS and StpA could cause misregulation of transcription. For example, H-NS and Rho coordinate to regulate transcriptional termination and the absence of H-NS may cause increased transcriptional readthrough of Rho-dependent terminators [64]. Thus, it seems likely that our analysis provides an underestimate of the impact of H-NS on FNR function, since physiological conditions that alter H-NS activity are likely to have less severe effects on nucleoid structure.

Discussion

By combining genome-wide FNR occupancy data from ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip experiments with transcriptomic data, we uncovered new features of bacterial transcriptional regulation and the FNR regulon. Our findings suggest that in vivo FNR occupies only a subset of predicted FNR binding-sites in the genome, and that FNR binding can be blocked by NAPs like H-NS. Furthermore, the lack of correlation between match to consensus of FNR binding sites and ChIP enrichment suggests that variations in ChIP signal result from changes in cross-linking efficiency or epitope access rather than variable occupancy. We found that the FNR regulon is malleable; the set of genes controlled by FNR can be readily tailored to changing growth conditions that may activate or inactivate other TFs, allowing flexible reprograming of transcription. This strategy would allow the regulon to expand or contract depending on available nutrients, providing a competitive advantage in the ecological niche of E. coli of the mammalian gut [65].

FNR peak height does not correlate with the match to the FNR consensus site

The finding that there was little relationship between peak height and the quality of the FNR motif differs from the results found for LexA, which showed a correlation between peak height and match to consensus [10]. Our data suggest that FNR peak height may be more related to the efficiency of cross-linking or immunoprecipitation since sites that appear to be saturated for binding displayed significantly different peak heights. Thus, at least for FNR, peak height cannot be used to assess relative differences in site occupancy between chromosomal sites. Cross-linking or immunoprecipitation of FNR may be less efficient than for LexA because the larger number of other regulators bound at FNR-regulated promoters may affect accessibility to the cross-linking agent or FNR immunoprecipitation.

FNR sites having either a strong match to consensus (for example, ydfZ – TTGATaaaaAACAA) or a weak match (for example, frdA – TCGATctcgTCAAA) were saturated for binding at FNR dimer concentrations at its cellular level (∼2.5 µM) [37]; thus, in vivo most accessible FNR sites are likely to be fully occupied. These data also revealed that FNR occupancy was not significantly different for strong and weak sites over the tested range of FNR dimer concentrations, suggesting that in vivo FNR binding is unlikely to be dictated solely by the intrinsic affinity of FNR binding sites.

Genome-wide data reveal FNR binding throughout the chromosome is influenced by other cellular factors beyond the presence of a FNR motif

Our finding that not all predicted FNR binding sites are bound by FNR in vivo offers new insight into the accessibility of the genome for binding TFs. Previous studies have predicted anywhere from 12 to 500 FNR binding sites in the E. coli genome [66]–[69], depending on the algorithm used. Of the 187 FNR binding sites predicted here, only 63 contained a corresponding FNR ChIP-seq peak in the WT strain, suggesting many high quality FNR sites are not bound. Although some of these silent sites may result from false negatives in the ChIP experiments (e.g. failure to immunoprecipitate FNR bound at some sites), only five of the 124 silent FNR sites (acnA, aldA, hyfA, hmp and iraD) showed any evidence of FNR regulation in prior studies [70]. Rather, several lines of evidence suggest that binding of NAPs or other TFs masks FNR binding at many of these sites in vivo. First, we observed that binding sites for the NAPs IHF, H-NS, and Fis were statistically overrepresented at the positions of silent FNR binding sites, suggesting these proteins occlude FNR binding. Second, we found that in the absence of H-NS and StpA, additional FNR binding sites became available for FNR binding as detected by ChIP, suggesting that NAPs influence FNR site availability in vivo. A similar effect has been observed in eukaryotes, where extensive research on TF site availability has shown that chromatin structure in vivo can block binding of TFs (e.g. Pho4, Leu3 and Rap1) to high quality DNA binding sites [1], [2], [4]. Additionally, known changes to chromosomal structure by IHF, Fis, and H-NS have been shown to inhibit DNA binding of other proteins [7], [12], [71]. Thus, if the binding profiles of NAPs change under alternative growth conditions, then the occluded FNR binding sites would likely become available for FNR binding.

Nonetheless, the fact that the 207 FNR-enriched regions from this study included 80% of the 63 regions identified by Grainger et al. (Table S5), despite the difference in the growth conditions and experimental design [29], suggests that the overlapping subset of FNR binding events may reflect a core set that is insensitive to growth conditions or binding of other TFs. Furthermore, binding events specific to each growth condition may be reflective of either changes in accessibility of FNR to binding sites due to changes in DNA-binding protein distribution or perhaps increases in activity of a second TF that binds cooperatively. Other regulators, such as CRP, a closely related member of the FNR protein family, also appear to have more binding sites available genome-wide than are occupied in vivo under tested growth conditions. Shimada et al. identified 254 CRP-cAMP binding sites using Genomic SELEX screening, which was 3–4 fold more than the number of CRP sites previously identified by ChIP-chip experiments [72], [73]; thus not all chromosomal CRP sites appear to be accessible for binding, although additional experiments would be required to explicitly examine the accessibility of CRP binding sites throughout the genome. Taken together, these results suggest that the restrictive effect of chromosomal structure could influence TF binding beyond FNR.

Environmental stimuli that change NAP distribution would also change TF binding site accessibility and affect transcription. For example, as E. coli enters the mammalian GI tract, it experiences a temperature increase from ∼25°C to 37°C, and this increase in temperature has been shown to affect transcription of a number of operons, including increased expression of anaerobic-specific operons [74], [75]. Because H-NS binding is sensitive to changes in temperature [76], [77], an explanation for these temperature-dependent transcriptional changes [74], [75] could be genome-wide decreases in H-NS binding and distribution; these changes could increase the accessibility of the binding sites for FNR and other TFs to regulate transcription. Supporting this explanation, several genes with a temperature dependent increase in expression showed FNR binding and regulation in the absence of H-NS and StpA, including hlyE, feaR, yaiV, and torZ. The activity of NAPs can also be affected by the binding of other condition specific TFs. For example, ChIP-chip and Genomic SELEX analysis of the stationary phase LysR-type TF, LeuO, suggested that binding of LeuO antagonized H-NS activity, but not necessarily H-NS binding, throughout the genome in Salmonella enterica and E. coli [78], [79].

Thus, a picture emerges from our data that binding of FNR is dependent on characteristics of the genome beyond the presence of a FNR binding site; this restrictive effect of chromosome structure by NAPs may affect binding of other TFs in bacteria. NAPs have been shown to occlude and affect binding of TFs and other DNA binding proteins, such as restriction endonucleases and DNA methylation enzymes, suggesting a general role of NAPs in regulating genome accessibility by bending, wrapping and bridging the DNA structure [7], [12], [13], [27], [42], [76], [80], [81]. Additionally, NAPs influence DNA supercoiling, which has been shown to affect binding of the TFs Fis and OmpR in S. enterica [82], [83], providing another mechanism by which NAPs can change the chromosomal structure to influence TF-DNA binding. Taken together, our results support a dynamic model of complex genome structure that affects TF binding to control gene regulation in bacteria.

Condition-specific expression of the FNR regulon likely requires other transcription factors

Although expression of a subset of the operons in the FNR regulon appeared to require only FNR for regulation (Categories 1 and 2), our findings point to widespread cooperation between FNR and other TFs for condition-specific regulation (Categories 3 and 4). Changes in activity of these TFs would result in FNR regulation to adapt to changes in environment, such as growth in non-catabolite repressed carbon sources (CRP) [57], anaerobic respiration of nitrate (NarL and NarP) [19], and growth in iron-limiting conditions (Fur) [84]. Although this co-regulation provides insight into growth conditions that should allow FNR-dependent changes in gene expression, the synergistic regulators for many promoter regions bound by FNR are currently unknown (Category 5), but would likely be identified in future genome-scale studies using different growth conditions, particularly microaerobic growth, which has been shown to affect FNR regulation of virulence genes in the pathogen Shigella flexneri [85].

Overall, our results suggest that the regulation of a subset of FNR-dependent promoters in E. coli may depend on combinatorial regulation with other TFs, a mechanism that resembles regulation of eukaryotic promoters [8], [20], [86]. These experimental data support previous in silico regulatory models generated using published data [87]–[89], suggesting combinatorial regulation may be common in E. coli. Further, ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq analyses of other TFs in E. coli (e.g. CRP, Fis, and IHF) and Salmonella typhimurium (e.g. Sfh, a H-NS homolog), identified many TF binding sites that did not correlate with changes in gene expression in corresponding TF-specific transcriptomic experiments [30], [33], [73], [90], [91]. These results raise the possibility of potential combinatorial regulation for other TFs, although additional analysis is required to support this notion.

The indirect FNR regulon also involves other regulators

We found that FNR directly controls expression of five secondary regulators, most of which are also regulated by specific cofactors, suggesting that the scope of the indirect FNR regulon (Category 6) is also likely to change depending on growth conditions. Of the five regulators, three act in an apparent hierarchal manner. The small RNA FnrS, which is upregulated by FNR and is suggested to stimulate mRNA turnover, decreased the mRNA levels of multiple FnrS target genes in GMM [48], [49]. Expression of the TF CaiF was also activated by FNR, but the genes regulated by CaiF were not expressed in GMM because CaiF requires the effector carnitine to be active [92]. FNR activated BssR, a TF involved in biofilm formation. About ∼40 operons are thought to be controlled by BssR [93], but none of the five BssR-dependent operons in the FNR indirect regulon that we tested by qRT-PCR showed any change in expression in a BssR− strain (data not shown); thus, under our growth conditions, BssR appeared to be inactive.

FNR also directly repressed the expression of two TFs, including the pyruvate sensing TF PdhR which represses several operons in the absence of pyruvate [94], [95]. Although one might expect that PdhR repressed genes would increase anaerobically, many of these genes are redundantly repressed by ArcA (Park and Kiley, Personal Communication); thus the impact of PdhR may be negligible under anaerobic growth in GMM. Similarly, the TF GadE, which is active at low pH [96], was also directly repressed by FNR and accordingly the operons in the GadE regulon were not identified as part of the indirect FNR regulon in GMM.

Finally, we note the caveat that some operons that appear indirectly regulated by FNR may change expression as a result of indirect physiological and metabolic effects in a FNR− strain, which may alter the activity of other TFs, resulting in mis-regulation of operons. For example, our data show that FNR does not directly regulate arcA transcription, but previous results have suggested that ArcA activity may be affected by the metabolic changes that occur when fnr is deleted [97]. Thus, although a subset of ArcA regulatory targets (29 operons) showed potential indirect FNR regulation, such effects were likely caused by changes in the phosphorylation state of ArcA resulting from metabolic changes in a FNR- strain (Table S13) (Park and Kiley, Personal Communication).

In conclusion, our results reveal complex features of TF binding in bacteria and expand our understanding of how E. coli responds to changes in O2 and other environmental stimuli.

A subset of predicted FNR binding sites appear to be inhibited by NAPs and are available in the absence of H-NS and StpA, suggesting that the bacterial genome is not freely accessible for TF binding and that changes in TF binding site accessibility could result in changes in transcription. Finally, correlation of the occupancy data with transcriptomic data suggests that FNR serves as a global signal of anaerobiosis but the expression of a subset of operons in the FNR regulon requires other regulators sensitive to alternative environmental stimuli. This strategy is reminiscent of global regulation by CRP-cAMP [73] in that FNR, like CRP, is bound at many promoters under specific conditions without corresponding changes in mRNA levels, suggesting a common strategy whereby promoters are primed to be activated when the appropriate growth conditions are encountered.

Materials and Methods

Strains and growth conditions

All strains were grown in MOPS minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose (GMM) [98] at 37°C and sparged with a gas mix of 95% N2 and 5% CO2 (anaerobic) or 70% N2, 5% CO2, and 25% O2 (aerobic). Cells were harvested during mid-log growth (OD600 of ∼0.3 using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 25 UV/Vis Spectrophotometer). E. coli K-12 MG1655 (F-, λ-, rph-1) and PK4811 (MG1655 ΔfnrΩSpR/SmR) [99] were used for the ChIP-chip, ChIP-seq and transcriptomic experiments unless otherwise specified. All data obtained in this study used GMM as the growth media, and although we know that not all promoters directly regulated by FNR are expressed under these conditions, this has the advantage that both mutant and parental strains exhibit the same growth rate.

For experiments that varied the in vivo concentration of FNR, a strain that contained a single, chromosomal copy of WT fnr under the control of the Ptac promoter at the λ attachment site was constructed. Following digestion of pPK823 [99] with XbaI and HindIII, the DNA fragment containing fnr was cloned into the XbaI and HindIII sites of pDHB60 (ApR) [100] to form pPK6401. Plasmid pPK6401 was transformed into DHB6521 [100] and the Ptac-fnr construct was stably integrated into the λ attachment site using the Lambda InCh system as described [100] to produce PK6410. P1vir transduction was used to move the Ptac-fnr, ApR allele into strain PK8257, which contains the FNR activated ydfZ promoter-lacZ fusion and deletion of lacY. This strain was transformed with pACYClacIQ-CAM [101] to generate PK8263. To determine the effect of FNR on the expression of the BssR regulon, a ΔbssR strain was constructed by P1vir transduction of ΔbssR::kanR from the Keio collection [102] into MG1655 to generate PK8923. To determine the role of H-NS on FNR binding, first stpA was recombined with the CmR gene, cmr, using λ red recombination and the pSIM plasmid [103]. P1vir transduction introduced the Δhns::kanR allele from the Keio collection [102] into the strain lacking stpA to generate the Δhns/ΔstpA strain.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated as previously described [104]. The concentration of the purified RNA was determined using a NanoDrop 2100, while the integrity of the RNA was analyzed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and the RNA Nano LabChip platform (Agilent).

Whole genome transcriptomic microarray analysis

Total RNA (10 µg) from two biological replicates each of MG1655 (+O2 and −O2) and PK4811 was reverse transcribed using random hexamers (Sigma) and the SuperScript II Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The cDNA (1 µg) was fluorescently labeled with Cy3-labeled 9 mers (Tri-Link Biotechnologies) with Klenow Fragment (NEB) for 2 hours at 37°C and recovered using ethanol precipitation. Labeled dsDNA (2 µg) was hybridized onto the Roche NimbleGen E. coli 4plex Expression Array Platform (4×72,000 probes, Catalog Number A6697-00-01) for ∼16 hours at 42°C in a NimbleGen Hybridization System 4 (Roche NimbleGen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The hybridized microarrays were scanned at 532 nm with a pixel size of 5 µm using a GenePix 4000B Microarray Scanner (Molecular Devices), and the PMT was adjusted until approximately 1% of the total probes were saturated for fluorescence intensity. The data were normalized using the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) algorithm in the NimbleScan software package, version 2.5 [105]. ArrayStar 3.0 (DNASTAR) was used to identify genes that showed at least a two-fold change in expression between the WT and Δfnr strains and were significantly similar among biological replicates, using a moderated t-test (p-value<0.01) [106]. Genes were organized into operons using data from EcoCyc [70]. An operon was called differentially expressed (DE) if only one gene within an operon showed a statistically significant change in expression. NimbleGen microarrays identified 214 statistically significant DE genes that were contained within 134 operons

The anaerobic MG1655 and FNR− samples from the normalized whole genome expression microarray data from Kang et al. [18] were also analyzed. Genes were determined to be DE if they had a change in expression greater than or equal to two-fold and if the genes were found to be statistically similar between biological replicates using a t-test (p-value<0.01). An operon was called DE if only one gene within an operon showed a statistically significant change in expression. This analysis identified 204 significant DE genes in 130 operons. Sixty operons were found to be DE in both the NimbleGen and Kang et al. data sets (Table S8). Of the 70 operons found DE in only the Kang et al. data set, 41 operons were just below the significance threshold in the NimbleGen data set and 11 operons resulted from activation of the flagellar regulon due to an insertion upstream of flhDC, which was absent in the isolate of MG1655 used in this study.

The Δhns/ΔstpA aerobic and anaerobic expression data were obtained from stand specific, single stranded cDNA hybridized to custom designed, high-density tiled microarrays containing 378,000 probes from alternate strands, spaced every ∼12 bp through the genome as described previously [107] except Cy3 was used instead of Cy5. Microarray hybridization and scanning were performed as described above except that the PMT was adjusted until the median background value was ∼100. All probe data were normalized using RMA in the NimbleScan software package, version 2.5 [105]. Gene probe values found to be significantly different between two biological replicates using a Benjamini & Hochberg corrected t-test (p-value<0.05) were eliminated from further analysis. Genes were called DE if the median log2 values were different by more than two-fold and if the genes were significantly different using an ANOVA test (p-value<0.05).

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis

To enrich for mRNA from total RNA, the 23S and 16S rRNA were removed using the Ambion MICROBExpress kit (Ambion) following manufacturer's guidelines, except the total RNA was incubated with the rRNA oligonucleotides for one hour instead of 15 minutes. The rRNA depleted RNA samples isolated from two biological replicates of MG1655 and its FNR− derivative were processed by the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) for RNA-seq library creation and sequencing. The RNAs were chemically fragmented using RNA Fragmentation Reagents (Ambion) to the size range of 200–250 bp using 1× fragmentation solution for 5 minutes at 70°C (Ambion). Double stranded cDNA was generated using the SuperScript Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The Illumina Paired End Sample Prep kit was used for Illumina RNA-seq library creation using the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the fragmented cDNA was end repaired, ligated to Illumina specific adapters and amplified with 10 cycles of PCR using the TruSeq SR Cluster Kit (v2). Single-end 36 bp reads were generated by sequencing on the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx, using the TruSeq SBS Kit (v5) following the manufacturer's protocol. Resulting reads were aligned to the published E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome (U00096.2) using the software package SOAP, version 2.20 [108], allowing no more than two mismatches. Reads aligning to repeated elements in the genome (for example rRNA) were removed from analysis. For reads that had no mapping locations for the first 36 bp, the 3–30 bp subsequences were used in the subsequent mapping to the reference genome. Reads that had unique mapping locations and did not match annotated rRNA genes were used for further analysis. For each gene, the tag density was estimated as the number of aligned sequencing tags divided by gene size in kb and normalized using quantile normalization. The tag density data were analyzed for statistically significant differential expression using baySeq, version 2.6 [109] with a FDR of 0.01, and genes were organized into operons using data from EcoCyc [70]. An operon was called DE if only one gene within an operon showed a statistically significant change in expression. The RNA-seq analysis identified 133 statistically significant DE operons (197 genes). Altogether, microarray and RNA-seq experiments identified 258 operons DE by FNR and slightly fewer than half of these operons (122) were found in at least two of the transcriptomic experiments (Figure S5, Table S8).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by hybridization to a microarray chip or high-throughput sequencing

ChIP assays were performed as previously described [110], except that the glycine, the formaldehyde and the sodium phosphate mix were sparged with argon gas for 20 minutes before use to maintain anaerobic conditions when required. Samples were immunoprecipitated using polyclonal antibodies raised against FNR, IHF or H-NS, which had been individually absorbed against mutant strains lacking the appropriate protein. In the case of FNR, affinity purified antibodies were used in some experiments, purified using the method previously described [111]. For RNA Polymerase, a σ70 monoclonal antibody from NeoClone (W0004) or a RNA Polymerase ß monoclonal antibody from NeoClone (W0002) were used for immunoprecipitation. For FNR, neither lengthening the cross-linking time nor increasing or decreasing the amount of FNR antibody used in the ChIP protocol showed significant changes in the FNR ChIP-chip peak heights or number of peaks identified. For ChIP-chip, FNR (three samples), FNR− (one sample), β (two samples), H-NS (two samples) and IHF (two samples) were fluorescently-labeled using Cy3 (INPUT) and Cy5 (IP) and hybridized for ∼16 hours at 42°C in a NimbleGen Hybridization System 4 (Roche NimbleGen) to custom designed, high-density tiled microarrays containing 378,000 probes from alternate strands, spaced every ∼12 bp through the genome. The hybridized microarrays were scanned at 532 nm (Cy3) and 635 nm (Cy5) with a pixel size of 5 µm using a GenePix 4000B Microarray Scanner (Molecular Devices), and the PMT was adjusted until approximately 1% of the total probes were saturated for fluorescence intensity of each dye used. The NimbleScan software package, version 2.5 (Roche NimbleGen) was used to extract the scanned data. ChIP-chip data were normalized within each microarray using quantile normalization (“normalize.quantiles” in the R package VSN, version 3.26.0) [112] to correct for dye-dependent intensity differences as previously described [113]. Biological replicates were normalized between microarrays using quantile normalization as previously described [113], and the normalized log2 ratio values (IP over INPUT) were averaged. There was a strong correlation between enriched regions of ChIP-chip biological replicates (R = 0.7). ChIP-chip peaks for FNR, H-NS and IHF were identified in each data set by the peak finding algorithm CMARRT, version 1.3 (FDR of 0.01) [114] and proportional Z-tests were used to determine significant differences between proportional data.

For ChIP-seq experiments, 10 ng of immunoprecipitated and purified DNA fragments from the FNR (two biological replicates) and σ70 samples (two biological replicates from both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions), along with 10 ng of input control, were submitted to the University of Wisconsin-Madison DNA Sequencing Facility (FNR samples and one σ70 sample) or the Joint Genome Institute (one σ70 sample) for ChIP-seq library preparation. Samples were sheared to 200–500 nt during the IP process to facilitate library preparation. All libraries were generated using reagents from the Illumina Paired End Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) and the Illumina protocol “Preparing Samples for ChIP Sequencing of DNA” (Illumina part # 11257047 RevA) as per the manufacturer's instructions, except products of the ligation reaction were purified by gel electrophoresis using 2% SizeSelect agarose gels (Invitrogen) targeting either 275 bp fragments (σ70 libraries) or 400 bp fragments (FNR libraries). After library construction and amplification, quality and quantity were assessed using an Agilent DNA 1000 series chip assay (Agilent) and QuantIT PicoGreen dsDNA Kit (Invitrogen), respectively, and libraries were standardized to 10 µM. Cluster generation was performed using a cBot Single Read Cluster Generation Kit (v4) and placed on the Illumina cBot. A single-end read, 36 bp run was performed, using standard SBS kits (v4) and SCS 2.6 on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx. Basecalling was performed using the standard Illumina Pipeline, version 1.6. Sequence reads were aligned to the published E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome (U00096.2) using the software packages SOAP, version 2.20, [108] and ELAND (within the Illumina Genome Analyzer Pipeline Software, version 1.6), allowing at most two mismatches. Sequence reads with sequences that did not align to the genome, aligned to multiple locations on the genome, or contained more than two mismatches were discarded from further analysis (<10% of reads). For visualization the raw tag density at each position was calculated using QuEST, version 1.2 [115], and normalized as tag density per million uniquely mapped reads. The read density was determined for each base in the genome for the IP and INPUT samples for FNR and σ70 samples. For FNR, peaks were identified using three peak finding algorithms: CisGenome, version 1.2, NCIS, version 1.0.1, and MOSAiCS, version 1.6.0 [116]–[118] (FDR for all of 0.05), while σ70 peaks were identified using NCIS, version 1.0.1 (FDR of 0.05). Further discussion of these algorithms is in Text S1. Differences between aerobic and anaerobic σ70 ChIP-seq occupancy were determined using a one-sided, paired t-test (p-value<0.01) comparing 100 bp surrounding the center of each peak. To normalize between +O2 and −O2 samples, the read counts for the enriched regions (peaks) for each sample were shifted by the negative median read count value of the background (un-enriched) signal. The p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni method to correct for multiple testing. There was a strong correlation between ChIP-seq biological replicates (R = 0.8) as well as between ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq data (Figure S6). All data were visualized in the MochiView browser [119].

Additional ChIP-chip -O2 data sets were performed for WT FNR and a Δfnr [99] control. The 15 FNR peaks identified only in ChIP-chip had low IP/INPUT ratios and were eliminated since ChIP-seq is known to have increased signal to noise relative to ChIP-chip [120]. The Δfnr -O2 ChIP-chip data identified 71 peaks that corresponded to peaks in the FNR -O2 ChIP-seq data, indicating they were not FNR specific, and were removed from the FNR ChIP-seq dataset (Table S5).

FNR PWM construction and identification of predicted FNR binding sites at FNR ChIP-seq peaks

To construct the FNR PWM, the sequence of a region of ∼100 bp around the nucleotide with the largest tag density within each of the FNR ChIP-seq peaks (the summit of each peak) found by all three peak finding algorithms was analyzed. MEME was used to identify over-represented sequences [121] and the Delila software package was used to construct the PWMs [122]. To search all ChIP-seq peaks for the presence of the FNR PWM, a region of 200 bp around the summit of each FNR ChIP-seq peak was searched with the FNR PWM using PatSer, version 3e [36], and the top four matches to the FNR PWM, as determined by PatSer PWM score, were recorded at each ChIP-seq peak. The standard deviation of the PatSer scores for the four FNR predicted binding sites at each ChIP-seq peak was determined and used as a threshold to determine the number of predicted binding sites at each peak. If the PatSer predicted FNR binding site at a peak with the highest PatSer score was more than one standard deviation greater than the PatSer predicted FNR binding site with the second best PatSer score, that peak was identified as having only one predicted FNR binding site. For FNR peaks (∼11%) with the two best PatSer predicted FNR binding site scores less than one standard deviation apart, a Grubbs test for outliers was used a single time to identify outliers within the four PatSer predicted FNR binding sites at a peak (α of 0.15, critical Z of 1.04). If a PatSer predicted FNR binding site at a FNR peak was identified as an outlier, it was removed from analysis and the standard deviation was re-calculated using the remaining three PatSer binding site scores at that peak. The remaining PatSer predicted FNR binding sites at the FNR peak were then re-examined as described above. After removing outlier PatSer predicted FNR binding sites, a peak was determined to contain two predicted FNR binding sites if the two best predicted FNR binding sites at that peak had PatSer scores less than one standard deviation apart.

The precision-recall curve was constructed using the FNR PWM and searching throughout the genome using PatSer, version 3e [36]. Precision was defined as True Positives (locations with a FNR ChIP-seq peak and a predicted FNR binding site) divided by True Positives plus False Positives (locations with a predicted FNR binding site but no FNR ChIP-seq peak). Recall was defined as True Positives divided by True Positives plus False Negatives (locations with a FNR ChIP-seq peak but no FNR predicted binding site). A high precision value means all predicted binding sites are true positives, but there is a high false negative rate. A high recall value means all true positives have been captured, but there is a high false positive rate.

Controlling expression of fnr with an IPTG-inducible promoter and performing ChIP-chip and analysis

The strain with fnr under the control of Ptac (PK8263) was used to study changes in [FNR] on ChIP-chip peak height. Cultures were grown anaerobically overnight in MOPS+0.2% glucose and were subcultured to a starting OD600 of ∼0.01 in MOPS+0.2% glucose plus Cm20 and various [IPTG] (4 µM IPTG, 8 µM IPTG, and 16 µM IPTG). After this initial step, growth, ChIP-chip experiments (two biological replicates of 4 and 8 µM IPTG and three biological replicates of 16 µM IPTG were used) and initial analysis were identical to the procedures described above. Estimates of FNR concentration were determined by quantitative Western blot as previously described [37]. A novel method of normalization was developed to compare peak areas between IPTG concentrations for 35 peaks that showed a large distribution in peak heights and 4 peaks that were classified as false positives by enrichment in the Δfnr ChIP-chip sample. The peak finding algorithm CMARRT identified peaks in the WT FNR ChIP-chip sample, and this peak region was trimmed to include the center 50% of the peak region. This trimmed region was used for each [IPTG] sample for consistency. For each of the 39 peaks examined, the probe values in a region of ∼3000 bp beyond the peak boundary (∼1500 bp upstream and downstream of the peak boundary) was selected for analysis from each sample. Within the ∼3000 bp region, the probes beyond the peak boundary were considered background for each sample. The median of the background (un-enriched) probes was calculated and the log2 IP/INPUT probe values for the entire peak region (enriched and un-enriched) were shifted by the negative median value of the background probes. The peak average (average of log2 IP/INPUT values) and standard deviation was determined for 39 peak regions to compare between samples at each [IPTG] and WT ChIP-chip samples. A one-sided, paired t-test was performed between all conditions (p-value<0.05) to determine statistically significant changes in average peak values.

Comparing FNR enrichment in WT and Δhns/ΔstpA genetic backgrounds using ChIP-chip analysis

Growth, ChIP-chip experiments, normalization and peak calling was performed as described above. To normalize between WT and Δhns/ΔstpA samples, the enriched regions (peaks) for each sample were shifted by the negative median log2 IP/INPUT value of the background (un-enriched) probes. The peak averages (average of log2 IP/INPUT values) were determined for each condition (WT and Δhns/ΔstpA) at each FNR peak found in either strain background. A one-sided, paired t-test with Bonferroni correction was performed between the two conditions (p-value<0.05) to determine the statistically significant change in peak averages. For peaks found in both WT and Δhns/ΔstpA, peaks were identified as significantly higher in Δhns/ΔstpA using a one-sided, paired t-test with Bonferroni correction performed between the two conditions (p-value<0.05) and if the FNR peak average in the Δhns/ΔstpA strain was greater than the standard deviation found for WT peak average.

Data deposition and visualization