-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaCatch Me If You Can: The Link between Autophagy and Viruses

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Pathog 11(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004685

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004685Summary

article has not abstract

What Is Autophagy?

Autophagy is a process that mediates the degradation of cytoplasmic material, such as damaged organelles and protein aggregates, to maintain cellular homeostasis (Fig. 1) [1]. The autophagic pathway begins with the sequestration of organelles and portions of the cytoplasm via a double-membrane termed the isolation membrane (or phagophore), which can be derived from several cellular compartments (including the endoplasmic reticulum [ER], Golgi complex, ER-Golgi intermediate compartment [ERGIC], mitochondria, or ER-mitochondria associated membranes [MAMs], as well as the plasma membrane) [2]. The isolation membrane expands to completely envelop the isolated contents in a double-membrane vesicle called the autophagosome, which then undergoes maturation through fusion with lysosomes to form autolyosomes [3]. A hallmark of canonical autophagy (or “macroautophagy”) is autophagic flux, in which lysosomal enzymes degrade the contents within the autolysome. Alternatively, early/late endosomes can fuse with autophagosomes, forming amphisomes that can then mature to autolysosomes, in which both endosomal and autophagosomal contents are degraded.

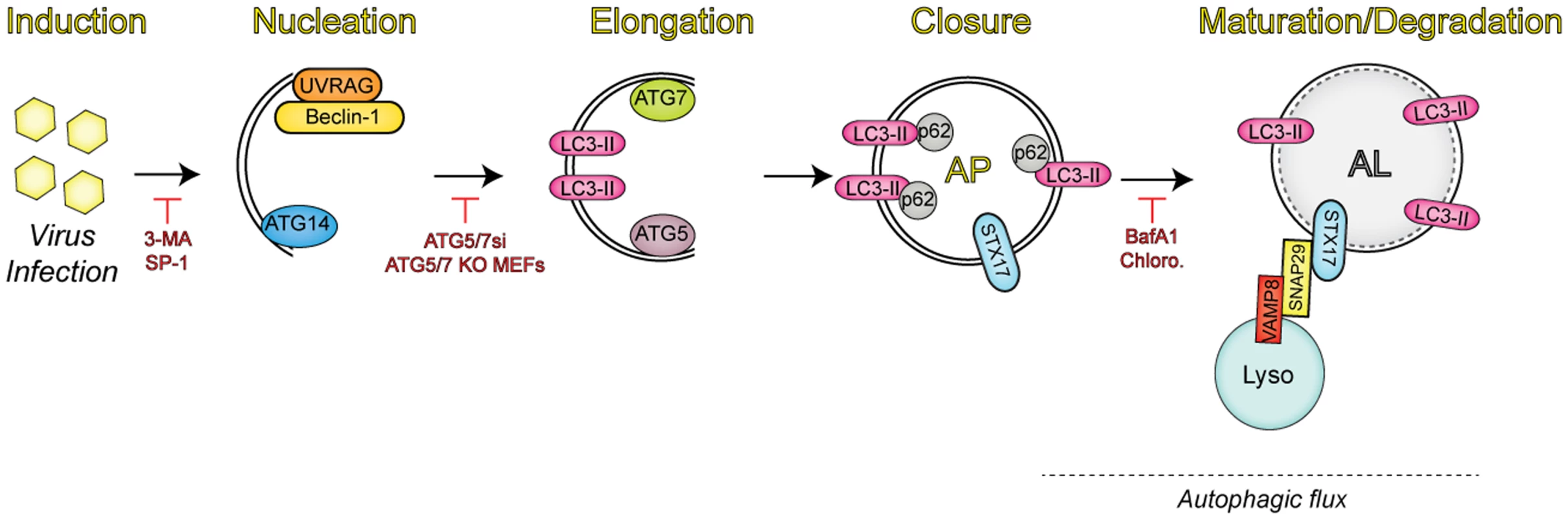

Fig. 1. Overview of the autophagic pathway.

Upon infection, viruses trigger the induction of autophagy through a number of mechanisms. Autophagy regulators (i.e., Beclin-1, UVRAG, and ATG14) function in membrane nucleation to form the double-membraned phagophore, which can be blocked via addition of pharmacological inhibitors (3-MA, spautin-1 [SP-1]). Additional autophagy-related proteins (ATG7 and ATG5) mediate the elongation step, in which the phagophore begins to expand until it closes around the material targeted for degradation by sequestration proteins, such as SQSTM/p62. Inhibition of this event is commonly performed through the expression of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting the autophagic components involved in this process. The completed autophagosome (AP) is then able to fuse with lysosomes (Lyso) via the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex consisting of syntaxin 17 (STX17), SNAP29, and VAMP8. The engulfed contents are then degraded, along with the inner membrane in the newly formed autolysosome (AL), in a process termed autophagic flux. Vesicle acidification inhibitors have been used to block degradation in the AL, given that lysosomal proteases are only active at low pH. Autophagy during Viral Infections: A Blessing in Disguise?

Autophagy is thought to be an ancient process that may have evolved to combat infection by a number of intracellular pathogens [4]. Work from our laboratory has shown that autophagy is induced by placental-derived microRNAs (miRNAs) carried in exosomes to attenuate viral infections in non-placental cells [5]. Furthermore, human placental trophoblasts, the specialized cells that comprise the placenta, exhibit high levels of autophagy themselves, which might contribute to their resistance to viral infections [5]. Autophagy is often a constitutive process that occurs at basal levels to maintain cellular homeostasis. However, autophagy can also be induced in response to cellular stresses such as nutrient deprivation, the unfolded protein response (UPR), or oxidative stress [6]. Given the amount of stress a viral infection elicits within a host cell, it is not surprising that this event often triggers autophagy, which can function as either a proviral or antiviral pathway, depending on the viral inducer.

Autophagosome formation requires extensive membrane remodeling, which is also induced during the replication of positive-strand RNA viruses. Indeed, many positive strand RNA viruses including picornaviruses and flaviviruses induce the autophagic process during their replicative life cycles to generate the membranes necessary for the biogenesis of their replication organelles. In addition, a diverse array of other viruses also induce autophagy (reviewed in [4]), including members of the paramyxoviridae, orthomyxoviridae, togaviridae, and herpesviridae. During infection, viruses (and/or virally-encoded proteins) can be targeted for degradation by induction of the autophagic pathway as a means to control their replication. For example, Sindbis virus capsid protein is targeted to autophagosomes and degraded during the process of autophagic flux, which functions to suppress new virion formation [7]. Interestingly, several herpesviruses express proteins that directly inhibit the formation of autophagosomes, indicating that these viruses may have evolved strategies to evade the degradative nature of the autophagic pathway [4]. Indeed, decreased neurovirulence is observed in mice infected with a mutant herpes simplex virus-1 that is unable to block autophagosome formation [8].

Host cells induce the formation of autophagosomes through a variety of mechanisms and in response to several events during the viral life cycle. During antiviral signaling, engagement of vesicular stomatitis virus by the pattern recognition receptor Toll-7 at the cell surface induces an autophagy-dependent innate immune response mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt-signaling in Drosophila that limits viral replication [9,10]. In addition, autophagy controls Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) replication in both flies and mammals via toll-like receptor signaling [11]. Some viruses induce autophagy at the earliest stages of their life cycles—measles virus (MeV) induces autophagy through binding to CD46, a cell surface receptor required for MeV entry [12]. At later stages of infection, expression of the MeV C protein is sufficient to induce a second wave of autophagy via interaction with immunity-associated GTPase family M (IRGM), a known regulator of autophagy [13]. Consistent with this, several other viruses have been shown to induce the formation of autophagosomes at late stages of their replicative life cycles, often as a consequence of the dramatic increases in protein production resulting from viral gene expression. For example, it has been reported that hepatitis C virus (HCV) induces autophagy through interaction with IRGM and ER stress by triggering the UPR [13,14]. The autophagic machinery has been shown to be involved in the initial translation of HCV RNA, but not maintenance of viral replication [15]. Several other viruses benefit from the induction of autophagy and have evolved strategies to directly manipulate the autophagic machinery in order to enhance their replication and/or egress.

How Do Viruses Benefit from Autophagy?

Enteroviruses have been extensively studied for the beneficial role that autophagy plays in their replicative life cycles. Replication of several members of the enterovirus family including poliovirus (PV) and coxsackievirus B (CVB) is enhanced by virus-induced autophagy [16,17]. Both PV and CVB infection results in the formation of autophagosome-like double-membraned vesicles, which serve as scaffolding for viral RNA replication [16,18]. Thus, these viruses usurp the autophagic pathway to provide the membranes necessary for these replication sites. It has been suggested that acidification of vesicles, potentially maturing autophagosomes, during PV infection promotes maturation of virions to the infectious particles [19]. However, autophagy-dependent degradation is not required for PV replication [19]; thus, maturation of virions does not depend on the degradative capacity of autolysosomes. Furthermore, a recent report suggests that PV takes advantage of autophagy-dependent exocytosis to aid in the release of virions into the extracellular space prior to viral-mediated lysis of the host cell in a process termed autophagosome-mediated exit without lysis (AWOL) [20]. Consistent with this finding, CVB can also be released in microvesicles containing the autophagosomal marker, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3-II) [21]. Unlike PV, CVB infection has been suggested to block the formation of autolysosomes, which has been hypothesized to be a mechanism to evade lysosomal degradation [17]. However, the role autophagic flux might play in CVB replication remains unclear. Although the precise mechanism(s) by which PV and CVB induce the autophagic pathway and manipulate select aspects of autophagy require further delineation, it is clear that autophagy plays an important role in the enhancement of enterovirus infection, most likely independent of autophagic flux.

In direct contrast to enteroviruses, MeV replication benefits from autophagic flux. Despite the completion of the autophagic maturation process, MeV proteins are not targeted for degradation by autophagosome-lysosome fusion [22]. Rather, induction of autophagy during MeV infection serves to prevent the induction of cell death. Given the role of autophagy in maintaining cellular homeostasis, it may not be surprising that infection activates this pro-survival pathway to prolong the life of the cell in order to generate a maximal number of progeny virions.

Similar to PV, autophagy also benefits the maturation of dengue virus (DENV) particles [23]. After replication in ER-associated vesicles, DENV particles are assembled in the ER and transported through the secretory pathway prior to their release into the extracelluar space. Within the Golgi complex, one of the viral surface glycoproteins, prM, is cleaved by the resident trans-Golgi protease furin, which results in the generation of infectious viral particles [24]. Inhibition of autophagy decreases the specific infectivity of extracellular virions, which corresponds with the observed decrease in prM cleavage on virions released from the cell.

Unlike enteroviruses, DENV directly benefits from a specific autophagy-dependent process termed “lipophagy” to increase its replication. Lipophagy represents an alternative pathway of lipid metabolism and is mediated by the degradative nature of autophagic flux. During DENV infection, lipid droplets colocalize with autolysosomes, which correlates with a decrease in cellular triglycerides [25]. Consequently, the released free fatty acids from lipid droplets are processed in the mitochondria via β-oxidation, resulting in an increase in cellular ATP. It has been proposed that this increase in ATP provides the source of energy required to facilitate the various processes involved in DENV replication. Thus, DENV infection induces autophagy-dependent lipid metabolism (“lipophagy”) to facilitate its replication. In another study, it was proposed that inhibition of autophagosome formation dramatically limits, but does not completely abolish, DENV replication [26]. Thus, either DENV does not absolutely require autophagy for replication or there are additional, yet to be defined pathways that regulate autophagosome formation during infection.

What Mechanisms Mediate Viral Manipulation of Autophagy?

A recent report has shown that human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) infection induces the accumulation of cytoplasmic autophagosomes by the direct inhibition of autophagic flux [27]. Autolysosome formation is dependent on the interaction of three SNAREs. Fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes is dependent on binding of the adaptor protein SNAP29 with syntaxin-17, located on the autophagosomal membrane, and the late endosome/lysosome membrane protein VAMP8 [28]. Expression of the HPIV3 phosphoprotein (P) inhibits the interaction of syntaxin-17 with SNAP29 by specifically interacting with both SNARE domains of SNAP29, thus directly inhibiting the ability of autophagosomes to fuse with lysosomes [27]. The inhibition of autolysosome formation results in an increase in extracellular virion production by a currently unknown mechanism [27].

Accumulation of autophagosomes is also observed during influenza A virus (IAV) infection [29]. The viral matrix 2 (M2) ion-channel protein contains a highly conserved LC3-interacting region (LIR) that mediates its interaction with the autophagosome-associated component LC3. Upon infection, LC3 relocalizes to the plasma membrane in an M2 LIR-dependent manner. Disruption of M2-LC3 interactions decreases filamentous virion budding and stability. Thus, in addition to modulating cell death pathways [30], IAV infection may subvert autophagy to enhance transmission to new cells and/or hosts by increasing virion stability.

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infection also results in the subversion of the autophagic pathway to facilitate new virion formation [31]. The HIV-1 precursor protein Gag interacts with LC3, which facilitates the processing of Gag into the virion core structural proteins. Furthermore, the HIV-1 accessory protein Nef blocks autophagosome maturation through its interaction with Beclin-1, a central regulator of autophagy. Deletion of Nef from the viral genome leads to autophagy-dependent degradation of the viral capsid protein p24. Therefore, HIV-1 infection requires the induction of autophagy for Gag processing, but inhibits the degradative capacity of this pathway to increase virion production.

Perspectives

Despite our appreciation that many viruses utilize autophagy in a proviral manner, relatively little is known regarding the specific mechanisms by which viruses induce autophagy and/or manipulate this pathway for their gain. In addition, the term “autophagy” most commonly refers to macroautophagy, a non-selective process that mediates bulk degradation, but there are many selective forms of autophagy that are named after the degradation targets, including mitophagy (mitochondria); pexophagy (peroxisomes); aggrephagy (protein aggregates); glycophagy (glycogens); lipophagy (lipids); and, recently, ER-phagy (endoplasmic reticulum) (reviewed in [32]). It will, therefore, be important to determine if these specialized autophagic processes are exploited by viruses to enhance their infection, as has been described for DENV and lipophagy. Recent work from our laboratory has identified a novel regulator of a noncanonical autophagic pathway that functions independent of the core initiation machinery to limit enterovirus infection [33], suggesting that enteroviruses might target noncanonical forms of autophagy to maximize their replication. In addition, the recent identification of specific regulators of autophagosome maturation, such as syntaxin-17, SNAP29, and VAMP8, presents an exciting opportunity to further define the role of this critical autophagic process in limiting and/or enhancing viral infections. The identification of specific regulators of the various stages of autophagy may also serve to clarify seeming inconsistencies in the literature, which were often published prior to the identification of these regulators. Although the field of autophagy is rapidly progressing, there is still much to be learned regarding the specific molecules that regulate this tightly controlled pathway and the mechanisms by which viruses target these molecules to facilitate their replication.

Zdroje

1. Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P (2013) Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol 15 : 713–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb2788 23817233

2. Tooze SA, Yoshimori T (2010) The origin of the autophagosomal membrane. Nat Cell Biol 12 : 831–835. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-831 20811355

3. Eskelinen EL (2005) Maturation of autophagic vacuoles in Mammalian cells. Autophagy 1 : 1–10. 16874026

4. Deretic V, Levine B (2009) Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe 5 : 527–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016 19527881

5. Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, et al. (2013) Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 12048–12053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304718110 23818581

6. Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B (2010) Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 40 : 280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023 20965422

7. Orvedahl A, MacPherson S, Sumpter R Jr., Talloczy Z, Zou Z, et al. (2010) Autophagy protects against Sindbis virus infection of the central nervous system. Cell Host Microbe 7 : 115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.007 20159618

8. Orvedahl A, Alexander D, Talloczy Z, Sun Q, Wei Y, et al. (2007) HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe 1 : 23–35. 18005679

9. Nakamoto M, Moy RH, Xu J, Bambina S, Yasunaga A, et al. (2012) Virus recognition by Toll-7 activates antiviral autophagy in Drosophila. Immunity 36 : 658–667. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.003 22464169

10. Shelly S, Lukinova N, Bambina S, Berman A, Cherry S (2009) Autophagy is an essential component of Drosophila immunity against vesicular stomatitis virus. Immunity 30 : 588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.009 19362021

11. Moy RH, Gold B, Molleston JM, Schad V, Yanger K, et al. (2014) Antiviral autophagy restrictsRift Valley fever virus infection and is conserved from flies to mammals. Immunity 40 : 51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.020 24374193

12. Joubert PE, Meiffren G, Gregoire IP, Pontini G, Richetta C, et al. (2009) Autophagy induction by the pathogen receptor CD46. Cell Host Microbe 6 : 354–366. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.006 19837375

13. Gregoire IP, Richetta C, Meyniel-Schicklin L, Borel S, Pradezynski F, et al. (2011) IRGM is a common target of RNA viruses that subvert the autophagy network. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002422. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002422 22174682

14. Ke PY, Chen SS (2011) Activation of the unfolded protein response and autophagy after hepatitis C virus infection suppresses innate antiviral immunity in vitro. J Clin Invest 121 : 37–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI41474 21135505

15. Dreux M, Gastaminza P, Wieland SF, Chisari FV (2009) The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 14046–14051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907344106 19666601

16. Jackson WT, Giddings TH Jr., Taylor MP, Mulinyawe S, Rabinovitch M, et al. (2005) Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol 3: e156. 15884975

17. Wong J, Zhang J, Si X, Gao G, Mao I, et al. (2008) Autophagosome supports coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J Virol 82 : 9143–9153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-08 18596087

18. Schlegel A, Giddings TH Jr., Ladinsky MS, Kirkegaard K (1996) Cellular origin and ultrastructure of membranes induced during poliovirus infection. J Virol 70 : 6576–6588. 8794292

19. Richards AL, Jackson WT (2012) Intracellular vesicle acidification promotes maturation of infectious poliovirus particles. PLoS Pathog 8: e1003046. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003046 23209416

20. Bird SW, Maynard ND, Covert MW, Kirkegaard K (2014) Nonlytic viral spread enhanced by autophagy components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 : 13081–13086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401437111 25157142

21. Robinson SM, Tsueng G, Sin J, Mangale V, Rahawi S, et al. (2014) Coxsackievirus B exits the host cell in shed microvesicles displaying autophagosomal markers. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004045. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004045 24722773

22. Richetta C, Gregoire IP, Verlhac P, Azocar O, Baguet J, et al. (2013) Sustained autophagy contributes to measles virus infectivity. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003599. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003599 24086130

23. Mateo R, Nagamine CM, Spagnolo J, Mendez E, Rahe M, et al. (2013) Inhibition of cellular autophagy deranges dengue virion maturation. J Virol 87 : 1312–1321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02177-12 23175363

24. Yu IM, Zhang W, Holdaway HA, Li L, Kostyuchenko VA, et al. (2008) Structure of the immature dengue virus at low pH primes proteolytic maturation. Science 319 : 1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1153264 18369148

25. Heaton NS, Randall G (2010) Dengue virus-induced autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 8 : 422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.006 21075353

26. Lee YR, Lei HY, Liu MT, Wang JR, Chen SH, et al. (2008) Autophagic machinery activated by dengue virus enhances virus replication. Virology 374 : 240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.016 18353420

27. Ding B, Zhang G, Yang X, Zhang S, Chen L, et al. (2014) Phosphoprotein of human parainfluenza virus type 3 blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion to increase virus production. Cell Host Microbe 15 : 564–577. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.04.004 24832451

28. Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Mizushima N (2012) The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell 151 : 1256–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.001 23217709

29. Beale R, Wise H, Stuart A, Ravenhill BJ, Digard P, et al. (2014) A LC3-interacting motif in the influenza A virus M2 protein is required to subvert autophagy and maintain virion stability. Cell Host Microbe 15 : 239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.01.006 24528869

30. Gannage M, Dormann D, Albrecht R, Dengjel J, Torossi T, et al. (2009) Matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus blocks autophagosome fusion with lysosomes. Cell Host Microbe 6 : 367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.005 19837376

31. Kyei GB, Dinkins C, Davis AS, Roberts E, Singh SB, et al. (2009) Autophagy pathway intersects with HIV-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J Cell Biol 186 : 255–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903070 19635843

32. Isakson P, Holland P, Simonsen A (2013) The role of ALFY in selective autophagy. Cell Death Differ 20 : 12–20. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.66 22653340

33. Delorme-Axford E, Morosky S, Bomberger J, Stolz DB, Jackson WT, et al. (2014) BPIFB3 regulates autophagy and coxsackievirus B replication through a noncanonical pathway independent of the core initiation machinery. MBio 5: e02147. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02147-14 25491355

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiologie Infekční lékařství Laboratoř

Článek A Phospholipase Is Involved in Disruption of the Liver Stage Parasitophorous Vacuole MembraneČlánek Host ESCRT Proteins Are Required for Bromovirus RNA Replication Compartment Assembly and FunctionČlánek Enhanced CD8 T Cell Responses through GITR-Mediated Costimulation Resolve Chronic Viral Infection

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Nejčtenější tento týden

2015 Číslo 3- Stillova choroba: vzácné a závažné systémové onemocnění

- Diagnostika virových hepatitid v kostce – zorientujte se (nejen) v sérologii

- Autoinflamatorní onemocnění: prognózu zlepšuje včasná diagnostika a protizánětlivá terapie

- Infekční komplikace virových respiračních infekcí – sekundární bakteriální a aspergilové pneumonie

- Kompletní remise ALK-pozitivního karcinomu plic u pacienta po mnoha liniích cílené léčby – kazuistika

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- To Be or Not IIb: A Multi-Step Process for Epstein-Barr Virus Latency Establishment and Consequences for B Cell Tumorigenesis

- Is Antigenic Sin Always “Original?” Re-examining the Evidence Regarding Circulation of a Human H1 Influenza Virus Immediately Prior to the 1918 Spanish Flu

- The Great Escape: Pathogen Versus Host

- Coping with Stress and the Emergence of Multidrug Resistance in Fungi

- Catch Me If You Can: The Link between Autophagy and Viruses

- Bacterial Immune Evasion through Manipulation of Host Inhibitory Immune Signaling

- Evidence for Ubiquitin-Regulated Nuclear and Subnuclear Trafficking among Matrix Proteins

- BILBO1 Is a Scaffold Protein of the Flagellar Pocket Collar in the Pathogen

- Production of Anti-LPS IgM by B1a B Cells Depends on IL-1β and Is Protective against Lung Infection with LVS

- Virulence Regulation with Venus Flytrap Domains: Structure and Function of the Periplasmic Moiety of the Sensor-Kinase BvgS

- α-Hemolysin Counteracts the Anti-Virulence Innate Immune Response Triggered by the Rho GTPase Activating Toxin CNF1 during Bacteremia

- Induction of Interferon-Stimulated Genes by IRF3 Promotes Replication of

- Intracellular Growth Is Dependent on Tyrosine Catabolism in the Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen

- HCV Induces the Expression of Rubicon and UVRAG to Temporally Regulate the Maturation of Autophagosomes and Viral Replication

- Spatiotemporal Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Infection

- Subgingival Microbial Communities in Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency and Their Relationship with Local Immunopathology

- Interaction between the Type III Effector VopO and GEF-H1 Activates the RhoA-ROCK Pathway

- Attenuation of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Using Large-Scale Random Codon Re-encoding

- Establishment of HSV1 Latency in Immunodeficient Mice Facilitates Efficient Reactivation

- XRN1 Stalling in the 5’ UTR of Hepatitis C Virus and Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Is Associated with Dysregulated Host mRNA Stability

- γδ T Cells Confer Protection against Murine Cytomegalovirus (MCMV)

- Rhadinovirus Host Entry by Co-operative Infection

- A Phospholipase Is Involved in Disruption of the Liver Stage Parasitophorous Vacuole Membrane

- Dermal Neutrophil, Macrophage and Dendritic Cell Responses to Transmitted by Fleas

- Elucidation of Sigma Factor-Associated Networks in Reveals a Modular Architecture with Limited and Function-Specific Crosstalk

- A Conserved NS3 Surface Patch Orchestrates NS2 Protease Stimulation, NS5A Hyperphosphorylation and HCV Genome Replication

- Host ESCRT Proteins Are Required for Bromovirus RNA Replication Compartment Assembly and Function

- Disruption of IL-21 Signaling Affects T Cell-B Cell Interactions and Abrogates Protective Humoral Immunity to Malaria

- Compartmentalized Replication of R5 T Cell-Tropic HIV-1 in the Central Nervous System Early in the Course of Infection

- Diminished Reovirus Capsid Stability Alters Disease Pathogenesis and Littermate Transmission

- Characterization of CD8 T Cell Differentiation following SIVΔnef Vaccination by Transcription Factor Expression Profiling

- Visualization of HIV-1 Interactions with Penile and Foreskin Epithelia: Clues for Female-to-Male HIV Transmission

- Sensing Cytosolic RpsL by Macrophages Induces Lysosomal Cell Death and Termination of Bacterial Infection

- PKCη/Rdx-driven Phosphorylation of PDK1: A Novel Mechanism Promoting Cancer Cell Survival and Permissiveness for Parvovirus-induced Lysis

- Metalloprotease NleC Suppresses Host NF-κB/Inflammatory Responses by Cleaving p65 and Interfering with the p65/RPS3 Interaction

- Immune Antibodies and Helminth Products Drive CXCR2-Dependent Macrophage-Myofibroblast Crosstalk to Promote Intestinal Repair

- Adenovirus Entry From the Apical Surface of Polarized Epithelia Is Facilitated by the Host Innate Immune Response

- The RNA Template Channel of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase as a Target for Development of Antiviral Therapy of Multiple Genera within a Virus Family

- Neutrophils: Between Host Defence, Immune Modulation, and Tissue Injury

- CD169-Mediated Trafficking of HIV to Plasma Membrane Invaginations in Dendritic Cells Attenuates Efficacy of Anti-gp120 Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies

- Japanese Encephalitis Virus Nonstructural Protein NS5 Interacts with Mitochondrial Trifunctional Protein and Impairs Fatty Acid β-Oxidation

- Yip1A, a Novel Host Factor for the Activation of the IRE1 Pathway of the Unfolded Protein Response during Infection

- TRIM26 Negatively Regulates Interferon-β Production and Antiviral Response through Polyubiquitination and Degradation of Nuclear IRF3

- Parallel Epigenomic and Transcriptomic Responses to Viral Infection in Honey Bees ()

- A Crystal Structure of the Dengue Virus NS5 Protein Reveals a Novel Inter-domain Interface Essential for Protein Flexibility and Virus Replication

- Enhanced CD8 T Cell Responses through GITR-Mediated Costimulation Resolve Chronic Viral Infection

- Exome and Transcriptome Sequencing of Identifies a Locus That Confers Resistance to and Alters the Immune Response

- The Role of Misshapen NCK-related kinase (MINK), a Novel Ste20 Family Kinase, in the IRES-Mediated Protein Translation of Human Enterovirus 71

- Chitin Recognition via Chitotriosidase Promotes Pathologic Type-2 Helper T Cell Responses to Cryptococcal Infection

- Activates Both IL-1β and IL-1 Receptor Antagonist to Modulate Lung Inflammation during Pneumonic Plague

- Persistence of Transmitted HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations Associated with Fitness Costs and Viral Genetic Backgrounds

- An 18 kDa Scaffold Protein Is Critical for Biofilm Formation

- Early Virological and Immunological Events in Asymptomatic Epstein-Barr Virus Infection in African Children

- Human CD8 T-cells Recognizing Peptides from () Presented by HLA-E Have an Unorthodox Th2-like, Multifunctional, Inhibitory Phenotype and Represent a Novel Human T-cell Subset

- Decreased HIV-Specific T-Regulatory Responses Are Associated with Effective DC-Vaccine Induced Immunity

- RSV Vaccine-Enhanced Disease Is Orchestrated by the Combined Actions of Distinct CD4 T Cell Subsets

- Concerted Activity of IgG1 Antibodies and IL-4/IL-25-Dependent Effector Cells Trap Helminth Larvae in the Tissues following Vaccination with Defined Secreted Antigens, Providing Sterile Immunity to Challenge Infection

- Structure of the Low pH Conformation of Chandipura Virus G Reveals Important Features in the Evolution of the Vesiculovirus Glycoprotein

- PPM1A Regulates Antiviral Signaling by Antagonizing TBK1-Mediated STING Phosphorylation and Aggregation

- Lipidomic Analysis Links Mycobactin Synthase K to Iron Uptake and Virulence in .

- Roles and Programming of Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE Proteins during Infection

- Impact of Infection on Host Macrophage Nuclear Physiology and Nucleopore Complex Integrity

- The Impact of Host Diet on Titer in

- Antimicrobial-Induced DNA Damage and Genomic Instability in Microbial Pathogens

- Herpesviral G Protein-Coupled Receptors Activate NFAT to Induce Tumor Formation via Inhibiting the SERCA Calcium ATPase

- The Causes and Consequences of Changes in Virulence following Pathogen Host Shifts

- Small GTPase Rab21 Mediates Fibronectin Induced Actin Reorganization in : Implications in Pathogen Invasion

- Positive Role of Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein in Type I Interferon Response and Its Regulation by Human Cytomegalovirus

- NEDDylation Is Essential for Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Latency and Lytic Reactivation and Represents a Novel Anti-KSHV Target

- β-HPV 5 and 8 E6 Disrupt Homology Dependent Double Strand Break Repair by Attenuating BRCA1 and BRCA2 Expression and Foci Formation

- An O Antigen Capsule Modulates Bacterial Pathogenesis in

- Variable Processing and Cross-presentation of HIV by Dendritic Cells and Macrophages Shapes CTL Immunodominance and Immune Escape

- Probing the Metabolic Network in Bloodstream-Form Using Untargeted Metabolomics with Stable Isotope Labelled Glucose

- Adhesive Fiber Stratification in Uropathogenic Biofilms Unveils Oxygen-Mediated Control of Type 1 Pili

- Vaccinia Virus Protein Complex F12/E2 Interacts with Kinesin Light Chain Isoform 2 to Engage the Kinesin-1 Motor Complex

- Modulates Host Macrophage Mitochondrial Metabolism by Hijacking the SIRT1-AMPK Axis

- Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 (HTLV-1) Tax Requires CADM1/TSLC1 for Inactivation of the NF-κB Inhibitor A20 and Constitutive NF-κB Signaling

- Suppression of RNAi by dsRNA-Degrading RNaseIII Enzymes of Viruses in Animals and Plants

- Spatiotemporal Regulation of a T4SS Substrate by the Metaeffector SidJ

- Antigenic Properties of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Envelope Glycoprotein Gp120 on Virions Bound to Target Cells

- Dependence of Intracellular and Exosomal microRNAs on Viral Oncogene Expression in HPV-positive Tumor Cells

- Identification of a Peptide-Pheromone that Enhances Escape from Host Cell Vacuoles

- Impaired Systemic Tetrahydrobiopterin Bioavailability and Increased Dihydrobiopterin in Adult Falciparum Malaria: Association with Disease Severity, Impaired Microvascular Function and Increased Endothelial Activation

- Transgenic Expression of the Dicotyledonous Pattern Recognition Receptor EFR in Rice Leads to Ligand-Dependent Activation of Defense Responses

- Comprehensive Antigenic Map of a Cleaved Soluble HIV-1 Envelope Trimer

- Low Doses of Imatinib Induce Myelopoiesis and Enhance Host Anti-microbial Immunity

- Impaired Systemic Tetrahydrobiopterin Bioavailability and Increased Oxidized Biopterins in Pediatric Falciparum Malaria: Association with Disease Severity

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Bacterial Immune Evasion through Manipulation of Host Inhibitory Immune Signaling

- BILBO1 Is a Scaffold Protein of the Flagellar Pocket Collar in the Pathogen

- Antimicrobial-Induced DNA Damage and Genomic Instability in Microbial Pathogens

- Attenuation of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Using Large-Scale Random Codon Re-encoding

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání