-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Call for Action: The Application of the International Health Regulations to the Global Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 8(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001022

Category: Policy Forum

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001022Summary

article has not abstract

Summary Points

-

The public health threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is growing and needs to be addressed urgently.

-

The International Health Regulations (IHR), a legally binding agreement between 194 States Parties, whose aim is to prevent, protect against, control, and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease, deserve critical examination with regard to their applicability to AMR.

-

We argue that the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, especially those involving new pan-resistant strains for which there are no suitable treatments, may constitute a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) and are notifiable to the World Health Organization under the IHR notification requirement.

-

The use of the IHR framework could considerably improve our response to emerging AMR threats like carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).

-

As more governments start to take the threat of pan-resistant bacteria seriously, there is a window of opportunity for having a healthy debate about the applicability of the IHR to AMR.

The unrelenting rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) constitutes a serious threat to health worldwide. In the last decade, challenging multi-resistant bacteria have expanded while new antimicrobial drug development has lagged [1] with little coordinated containment action at the global level. Of significant concern has been the emergence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-tuberculosis, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).

AMR in both humans and animals represents a complex global concern that must be addressed “urgently and aggressively” [2]. The International Health Regulations (IHR), a legally binding agreement between 194 States Parties [3], deserve critical examination with regard to their applicability to AMR. Using the example of CRE as point of departure, we analyze and discuss the potential role of the IHR with respect to AMR.

The Public Health Risk Posed by CRE

Enterobacteriaceae, a family that includes common pathogens responsible for a large spectrum of disease, have been sensitive to many antibiotics in the past. Since the 1980s, the global spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae has limited therapeutic options, but until recently, carbapenems were still a reliable treatment. The recent emergence of CRE, resistant to most classes of antibiotics, has necessitated the use of third-line agents and combination therapy with doubtful therapeutic efficacy and increased toxicity [4].

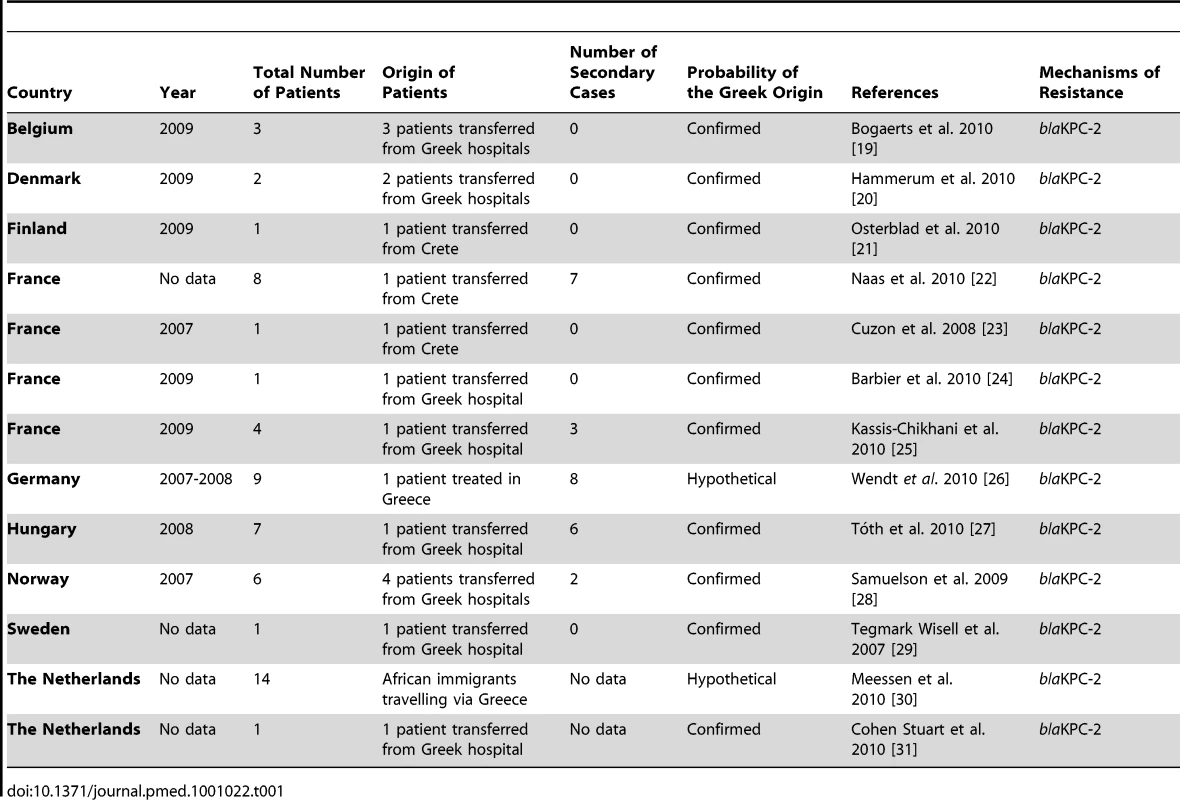

Klebsiella pneumoniae harboring KPC (KPC-Kp) have become endemic in parts of the United States, China, Israel, and Greece [4]. KPC-Kp have been imported from the United States to Israel, and from Israel to Colombia, the United Kingdom, and Greece. International spread of KPC-Kp from Greece has occurred to at least nine European countries since 2007 with further transmission documented in four of them (Table 1 and Figure S1). CRE-producing metallo-β-lactamases of the VIM family have become highly prevalent in Greece since their first detection in 2001 and spread to other countries in Europe and America [5]. NDM-1-producing CRE likely originated in India or Pakistan and have spread to four continents [6],[7].

CRE have been associated with increased mortality and morbidity, and higher treatment costs, when compared to infections caused by susceptible strains [8],[9], and have the potential to considerably increase the risk associated with routine medical procedures. Although CRE have emerged in hospitals, they will eventually spread to the community, similar to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, resulting in untreatable common infections in otherwise healthy individuals. CRE, particularly NDM-1, are already prevalent in the community in India and Pakistan [6].

The alarming spread of CRE is juxtaposed against our failure to develop new effective antimicrobials. The utility of tigecycline is marred by high rates of resistance among CRE [6] and a recent FDA safety warning [10]. The usefulness of colistin, the last drug with reliable in vitro activity, is limited by toxicity, moderate efficacy, and emergence of resistance [6]. Currently, not a single new agent to treat CRE infections is on the horizon. These observations suggest that the international spread of CRE constitutes a “cause for worldwide concern” [11].

The Shortcomings of Global AMR Surveillance and Control

Surveillance of AMR-pathogens such as CRE is patchy and limited by financial and technical constraints in large parts of the world. In some high-income countries, AMR data are compiled by publicly funded surveillance networks such as EARS-Net, a network of national surveillance systems in Europe, or by pharmaceutical company-sponsored surveys. Informal networks, such as ProMED, also collect information, although selectively and with a considerable time lag. This holds even truer for the scientific literature.

Improving AMR surveillance is one of the key recommendations in a recent report [2]. Without a global early warning system, the spread of AMR often remains unnoticed until a given strain has become endemic. Although data from Israel indicate that the countrywide adoption of enhanced hospital infection control measures was effective in reducing endemic KPC-Kp transmission, early proactive surveillance and containment strategies are more effective and much less costly [12]. In view of the shortcomings of the current patchwork, a coordinated response using a global framework for surveillance and enhanced infection control of CRE and other emerging XDR-pathogens is needed.

The Potential Role of the IHR

The IHR provide a legal framework for international efforts to contain the risk from public health threats that may spread between countries, including surveillance and global alerts (Articles 5–11), definition of core public health capacities for surveillance and response in all countries (Articles 5, 13), and World Health Organization (WHO) guidance through “standing recommendations” (Articles 16, 53) [3].

In order to identify events that have the “potential to cause international disease spread”, WHO is bound to collect epidemiologic information “through its surveillance activities” (Article 5), notifications from affected countries (Article 6), and reports from third parties (Article 9) [3]. A set of criteria defined in Annex 2 of the Regulations (Figure 1) is used to determine whether an event “may constitute a public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC) and “potentially requires a coordinated international response” [3]. The determination of a PHEIC constitutes a second and independent step from the notification process and falls within the purview of the Director-General of WHO.

We argue that certain events marking the emergence and international spread of KPC and NDM-1-producing CRE, especially those involving new pan-resistant strains for which there are no suitable treatments and which are of major public health importance, can be considered to fulfil at least two Annex 2 criteria, in particular “serious public health impact” and “international spread” (Table 2), and should therefore be notified to WHO. This argument has, in fact, been made for XDR-tuberculosis and can be extrapolated to other types of significant new or emerging extensively or pandrug-resistant pathogens such as artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. “New or emerging antibiotic resistance” is one of the examples listed in Annex 2 for application of the first criterion.

Still, due to the nonspecific nature of Annex 2 and limited WHO guidance, some may counter that CRE (and other AMR) events are irrelevant to the IHR. In a recent survey among National IHR Focal Points, a scenario describing a fatal hospital outbreak caused by pan-resistant K. pneumoniae was considered notifiable by just over half of respondents [13]. One of the main arguments against applying the IHR to AMR events is that “the IHR are really intended for outbreaks of acute disease” [14] rather than “acute-on-chronic” events like the relatively slow but relentless spread of AMR. However, we would counter that this reasoning is inconsistent with the explicitly stated purpose of the IHR “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of diseases in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade”[3].

Why Should the IHR Be Applied to the Global AMR Threat?

The global threat posed by the spread of AMR cannot be addressed by individual countries alone, but requires a coordinated international response. Recognizing the applicability of the IHR to AMR will serve as a “wake-up call” and strengthen global AMR surveillance and response, which could in turn contribute to containing the spread of AMR. While WHO has initiated several networks and provides guidance for reporting AMR, including WHONET, none function as an early warning system. Although very few AMR events would be determined a PHEIC by the Director-General, notifications of events that fulfil the Annex 2 criteria could serve as alerts and could be an important instrument in the chain of “the global early warning function, the purpose of which is to provide international support to affected countries and information to other countries if needed” [15]. The immediate consequence of notification is to initiate an “exclusive dialogue between the notifying State Party and WHO concerning the event at issue” [15] and to make a joint risk assessment. Once an event has been notified to WHO, and it is not determined to be a PHEIC, WHO can communicate this information to other countries (Article 11). The dissemination of information through the WHO Event Information System (EIS) could expediently increase awareness in multiple countries, allow early implementation of screening measures for persons at risk (e.g., international hospital transfers), and prevent the establishment of new resistant strains in unaffected countries. Based on the experience in Greece and Israel, Carmeli et al. recommend that countries “should be made aware of the problem and should have a preparedness plan ready for implementation at a national level” [16]. By authorizing WHO to make “standing recommendations” (Article 16), the IHR could facilitate the international dissemination of appropriate measures to counter the spread of AMR.

Importantly, the IHR focuses on a societal investment in core surveillance and response capacities at different levels by setting minimum standards. WHO pledges to collaborate with the States Parties concerned “by providing technical guidance and assistance and by assessing the effectiveness of the control measure in place, including the mobilization of international teams of experts for on-site assistance, when necessary”. This is relevant for the spread of AMR given the importance of appropriate infection control measures. While details of these measures need to be more closely defined, it is clear that the application of the IHR framework is invaluable for a coordinated global approach to AMR.

What Are the Obstacles to Apply the IHR to the Global Spread of AMR?

Even if WHO and a majority of States Parties considered that AMR should be addressed under the IHR, technical, financial, and political obstacles might interfere. Notification of an event to WHO depends on it being detected (requiring a functioning health system and adequate laboratory capacities), and reported to the National IHR Focal Point. There is concern that many States Parties are far from being compliant with the IHR's minimum core capacity requirements for surveillance and response. Even if relevant information filters through to the national level, notification decisions may be under political control. The fierce reaction of the Indian government to claims that NDM-1-producing CRE isolated in the UK originated in India casts doubt on the willingness of governments to report the existence of such events, in particular if economic interests (such as the income from medical tourism) are at stake. These obstacles are not specific to AMR-related events, and cannot serve as an argument against the application of the IHR in this context.

The final obstacles are a lack of expertise and capacities within WHO. Although WHO vertical programs have successfully focused on drug resistance in selected areas, including malaria and tuberculosis, WHO arguably does not have the means to comply with its IHR mandate of offering assistance to States Parties affected by the spread of multi-resistant bacteria. The dearth of leadership in this area was the object of a WHO resolution in 2005, but it has been commented that “very little has taken place to implement the resolution WHA 58.27 since its passage” [17]. During the last World Health Assembly, the Swedish Health Minister commented that “there is an increasing awareness about this major health threat, but far from enough action. The leadership of WHO is urgently needed in this area” [18].

IHR—A Call for Action

The IHR do not provide a panacea for the problem of AMR. However, this framework provides a global surveillance infrastructure and orchestrates an appropriate public health response. The IHR are ultimately “owned” by the States Parties, some of whom increasingly understand the extent and urgency of the threat posed by AMR. However, it is up to WHO to provide leadership on the role of the IHR in this matter. Further guidance on the application of Annex 2 to this issue is required. With the IHR in place, increasing the capacities of this framework at all levels to address AMR, rather than investing in new vertical programs, seems logical. The revival of the implementation of the WHO 2001 Global Strategy for the containment of AMR with incorporation of the IHR framework into the strategy is required. Although this paradigm shift eventually rests on the World Health Assembly and States Parties' willingness to adopt it, WHO must demonstrate leadership in this regard.

Conclusion

The international dissemination of AMR, typified by CRE, is a serious threat for global health. Although the spread of AMR is less dramatic than many acute disease outbreaks, it significantly reduces our therapeutic options and adds significantly to the health care burden. A global mechanism incorporating both systematic surveillance and effective public health response is urgently required. We would argue that the IHR provide an appropriate framework to coordinate efforts for controlling the international spread of AMR. Several obstacles need attention before the full potential of the IHR may be realized, but there is a window of opportunity for having a healthy debate about the applicability of the IHR to AMR. While States Parties and WHO share a collective responsibility in the process, WHO must clearly delineate its position with regard to AMR and the intended role of the IHR in this context.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BoucherHWTalbotGHBradleyJSEdwardsJEGilbertD

2009

Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious

Diseases Society of America.

Clin Infect Dis

48

1

12

2. NugentRBackEBeithA

Center for Global Development Drug Resistance Working Group

2010

The race against drug resistance.

Washington (D.C.)

Center for Global Development

3. World Health Organization.

2008

International health regulations (2005).

Geneva

World Health Organization

4. NordmannPCuzonGNaasT

2009

The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae

carbapenemase-producing bacteria.

Lancet Infect Dis

9

228

236

5. VatopoulosA

2008

High rates of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella

pneumoniae in Greece—a review of the current

evidence.

Euro Surveill

13

8023

6. KumarasamyKKTolemanMAWalshTRBagariaJButtF

2010

Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India,

Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological

study.

Lancet Infect Dis

10

597

602

7. RolainJMParolaPCornagliaG

2010

New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM-1): towards a new

pandemia?

Clin Microbiol Infect

12

1699

1701

8. SchwaberMJKlarfeld-LidjiSNavon-VeneziaSSchwartzDLeavittA

2008

Predictors of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella

pneumoniae acquisition among hospitalized adults and effect of

acquisition on mortality.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother

52

1028

1033

9. PatelGHuprikarSFactorSHJenkinsSGCalfeeDP

2008

Outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella

pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and

adjunctive therapies.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol

29

1099

1106

10. US Food and Drug Administration

2010

FDA drug safety communication: increased risk of death with Tygacil

(tigecycline) compared to other antibiotics used to treat similar

infections. Available: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm224370.htm. Accessed

14 March 2011

11. MoelleringRC

2010

NDM-1—a cause for worldwide concern.

New Eng J Med

363

2377

2379

12. SchwaberMJLevBIsraeliASolterESmollanG

2011

Containment of a country-wide outbreak of carbapenem-resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae in Israeli hospitals via a

nationally-implemented intervention.

Clin Infect Dis

52

1

8

13. HausteinTHollmeyerHHardimanMHarbarthSPittetD

2011

Should this event be notified to WHO?

Reliability of the International Health Regulations notification

assessment process. Bull WHO

In press

14. WHO Global Task Force on XDR-TB

2007

Report of the meeting of the WHO Global Task Force on XDR-TB,

9-10 October 2006.

Geneva

World Health Organization

15. World Health Organization

2008

WHO guidance for the use of Annex 2 of the International Health

Regulations (2005).

Geneva

World Health Organization

16. CarmeliYAkovaMCornagliaGDaikosGLGarauJ

2010

Controlling the spread of carbapenemase-producing Gram-negatives:

therapeutic approach and infection control.

Clin Microbiol Infect

16

102

111

17. ReAct

2007

Antibiotic resistance - a call for global

leadership.

Available: http://soapimg.icecube.snowfall.se/stopresistance/ReAct_response.pdf.

Accessed 14 March 2011

18. LarssonM

2010

Discourse at the the World Health Assembly.

Available: http://www.regeringen.se/sb/d/12546/a/146073. Accessed 14

March 2011

19. BogaertsPMontesinosIRodriguez-VillalobosHBlaironLDeplanoA

2010

Emergence of clonally related Klebsiella

pneumoniae isolates of sequence type 258 producing KPC-2

carbapenemase in Belgium.

J Antimicrob Chemother

65

361

362

20. HammerumAMHansenFLesterCHJensenKTHansenDS

2010

Detection of the first two Klebsiella pneumoniae

isolates with sequence type 258 producing KPC-2 carbapenemase in

Denmark.

Int J Antimicrob Agents

35

610

612

21. OsterbladMKirveskariJKoskelaSTissariPVuorenojaK

2009

First isolations of KPC-2-carrying ST258 Klebsiella

pneumoniae strains in Finland, June and August

2009.

Euro Surveill

14

19349

22. NaasTCuzonGBabicsAFortineauNBoytchevI

2010

Endoscopy-associated transmission of carbapenem-resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-2

{beta}-lactamase.

J Antimicrob Chemother

65

1305

1306

23. CuzonGNaasTDemachyMCNordmannP

2008

Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 in

Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from

Greece.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother

52

796

797

24. BarbierFRuppeEGiakkoupiPWildenbergLLucetJ

2010

Genesis of a KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

after in vivo transfer from an imported Greek strain.

Euro Surveill

15

19457

25. Kassis-ChikhaniNDecreDIchaiPSengelinCGenesteD

2010

Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing

KPC-2 and SHV-12 in a French hospital.

J Antimicrob Chemother

65

1539

1540

26. WendtCSchuttSDalpkeAHKonradMMiethM

2010

First outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae

carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae in

Germany.

Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis

29

563

570

27. TothADamjanovaIPuskasEJanvariLFarkasM

2010

Emergence of a colistin-resistant KPC-2-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone in

Hungary.

Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis

29

765

769

28. SamuelsenONaseerUToftelandSSkutlabergDHOnkenA

2009

Emergence of clonally related Klebsiella

pneumoniae isolates of sequence type 258 producing

plasmid-mediated KPC carbapenemase in Norway and Sweden.

J Antimicrob Chemother

63

654

658

29. Tegmark WisellKHaeggmanSGezeliusLThompsonOGustafssonI

2007

Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae

carbapenemase in Sweden.

Euro Surveill 12: E071220

071223

30. MeessenNWiersingaJvan der ZwaluwKvan AltenaR

2010

First outbreak of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella

pneumoniae in a tuberculosis care facility in the Netherlands.

Abstract number: P1283. Proceedings of the 20th European Congress of

Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID); 10 April–13

April, 2010; Vienna, Austria.

Available: http://registration.akm.ch/2010eccmid_einsicht.php?XNABSTRACT_ID=104079&XNSPRACHE_ID=2&XNKONGRESS_ID=114&XNMASKEN_ID=900.

Accessed 14 March 2011

31. Cohen StuartJWVoetsGVersteegDScharringaJTersmetteM

2010

The first carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella

pneumoniae strains in the Netherlands are associated with

international travel. Abstract number: P1284. Proceedings of the 20th

European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID);

10 April–13 April, 2010; Vienna, Austria.

Available: http://registration.akm.ch/2010eccmid_einsicht.php?XNABSTRACT_ID=103461&XNSPRACHE_ID=2&XNKONGRESS_ID=114&XNMASKEN_ID=900.

Accessed 14 March 2011

32. JohnsonRBeckerG

2010

US-Russia meat and poultry trade issues. Washington (D.C.):

Congressional Research Service for Congress.

Available: http://www.nationalaglawcenter.org/assets/crs/RS22948.pdf.

Accessed 14 March 2011

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2011 Číslo 4- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Ferinject: správně indikovat, správně podat, správně vykázat

- Optimální dávkování apixabanu v léčbě fibrilace síní

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Quality of Private and Public Ambulatory Health Care in Low and Middle Income Countries: Systematic Review of Comparative Studies

- A Multifaceted Intervention to Implement Guidelines and Improve Admission Paediatric Care in Kenyan District Hospitals: A Cluster Randomised Trial

- The Quality of Medical Care in Low-Income Countries: From Providers to Markets

- Neglect of Medical Evidence of Torture in Guantánamo Bay: A Case Series

- Improving Effective Surgical Delivery in Humanitarian Disasters: Lessons from Haiti

- Decline in Diarrhea Mortality and Admissions after Routine Childhood Rotavirus Immunization in Brazil: A Time-Series Analysis

- Effect of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination on Serotype-Specific Carriage and Invasive Disease in England: A Cross-Sectional Study

- Effect of a Nutrition Supplement and Physical Activity Program on Pneumonia and Walking Capacity in Chilean Older People: A Factorial Cluster Randomized Trial

- Strategies and Practices in Off-Label Marketing of Pharmaceuticals: A Retrospective Analysis of Whistleblower Complaints

- A Call for Action: The Application of the International Health Regulations to the Global Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance

- Medical Complicity in Torture at Guantánamo Bay: Evidence Is the First Step Toward Justice

- A Public Health Emergency of International Concern? Response to a Proposal to Apply the International Health Regulations to Antimicrobial Resistance

- Global Health Philanthropy and Institutional Relationships: How Should Conflicts of Interest Be Addressed?

- Claims about the Misuse of Insecticide-Treated Mosquito Nets: Are These Evidence-Based?

- The African Women's Protocol: Bringing Attention to Reproductive Rights and the MDGs

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Global Health Philanthropy and Institutional Relationships: How Should Conflicts of Interest Be Addressed?

- A Call for Action: The Application of the International Health Regulations to the Global Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance

- Claims about the Misuse of Insecticide-Treated Mosquito Nets: Are These Evidence-Based?

- Neglect of Medical Evidence of Torture in Guantánamo Bay: A Case Series

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání