-

Články

- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

FLEXIBLE TEG ON THE ANKLE FOR MEASURING THE POWER GENERATED WHILE PERFORMING ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING

Authors: Antonino Proto; Lukas Peter; Martin Augustynek; Martin Cerny; And Marek Penhaker

Authors place of work: Department of Cybernetics and Biomedical Engineering, VSB-TUO, Ostrava, Czech Republic

Published in the journal: Lékař a technika - Clinician and Technology No. 3, 2018, 48, 84-90

Category: Original research

Summary

In this work, a commercial flexible thermoelectric generator (f-TEG) was used to harvest the body thermal energy during the execution of activities of daily living (ADL). The f-TEG was placed at the level of the ankle, and the performed activities were sitting at the desk and walking. In the first stage of measurements, tests were performed to choose the value of the resistor load that maximizes the power output. Then, while performing ADL, the values of generated power were in the range from 100 to 450 µW. Moreover, while users are walking, the pattern of the output signal of f-TEG is compatible to a sine function with frequency close to that one of human gait. This preliminary result may represent a new way to study the movement of human body to recognize ADL.

Keywords:

thermoelectricity, thermal energy harvesting, flexible TEG, wearable, human body, activities of daily living

Introduction

Nowadays, wearables are commonly used to monitor the physiological signals of human beings, as they are low-cost and non-invasive devices [1, 2]. The main advantage of this technology is the capability of moni-toring bio-parameters in unstructured environment; by using wearable devices, it is possible to measure the health and safety of human beings wherever they are, e.g. at home, at work, or while they are performing lei-sure and sporting activities [3–9]. Moreover, wearables can compute the acquired data and transmit them by a wireless interface [10, 11].

However, the issue of wearables’ operating-time is a big challenge to solve, yet. It compromises the possi-bility of long-term monitoring [12]. By using a big battery is possible to overcome that issue, but the weight of the entire device would make it uncomfortable and not suitable for a daily use.

In this context, the research field of low power energy harvesting may fix the issue of wearables’ operating-time. It addresses the need for continuous power sup-plying, by harvesting the energy from the environment. The most available energy sources in nature are light, thermal energy, mechanical vibrations, and electro-magnetic waves [13].

About human body, it generates energy in the form of movement, and heat exchanged with the environment [14, 15]. However, the mechanical energy is provided only if the body is moving, while the thermal energy is always available, because the body disperses heat, continuously [16–17]. Thus, it seems to be appropriate do research on body thermal energy harvesting.

Thermal energy harvesting takes place by means of the thermoelectric effect, which was discovered by Seebeck in 1821, and it can be summarized as follows: by exploiting the thermal gradient between two dissimi-lar metals or semiconductors, it is possible to convert thermal energy into electrical one [18].

Nowadays, ThermoElectric Generators (TEGs) are the most used transducers to harvest the body heat released into the environment. A TEG consists of many p-n pairs, electrically connected in series; two ceramic plates, which make the TEG thermally conducting; and output wires for measuring and harvesting the energy. For on-body applications, the energy is generated by the difference of temperature between the two sides of TEG, which are the skin and the environment, respectively.

About the skin side, the temperature changes according to the body physiological parameters, and at the air temperature of 22.5 ± 1.7 °C is approximately 30 ± 2.5 °C [19]. About the environment side, air tem-perature, humidity and speed of tasks execution are the aspects that most influence the performance of TEG [20].

In the commercial market, TEGs are used to power wristwatches. Seiko Instruments Inc. designed the first wristwatch powered by TEGs at the end of ‘90s [21], while the latest novelty is the Matrix PowerWatch, which is a self-powered smart-watch [22].

About research groups that have developed prototypes powered by TEGs, we highlight the pulse oximeter and the 2-channel electroencephalography system devel-oped by IMEC engineers between 2006 and 2008 [23, 24]. These systems were powered by a TEG system able to generate approximately 2 mW, when the temper-ature difference between its two sides was approximate-ly 8 °C. However, the researchers stated that is very difficult maintain such gradient of temperature over a prolonged period.

In recent years, the main goal for designers all over the world is to reduce the TEG volume while keeping the output voltage on the order of hundreds of millivolts [25].

Anyway, the biggest issue for wearable application relates to the curved shape of human body. It means that a TEG must be flexible to fully adhere to the skin. There-fore, a new promising way for harvesting the thermal energy on the body involves the use of a flexible-TEG (f-TEG) [26, 27].

Moreover, despite a considerable number of scientific researches focusing on harvesting the thermal energy on the upper part of the body, there is a lack of information regarding the thermal energy harvested on legs [28, 29]. It could be useful to compare the values of the thermal power generated by legs while users are performing different Activities of Daily Living (ADL).

The detection of ADL by means of f-TEGs may represent an innovative way for the evaluation of ADL, since today the only way to study human activities through energy harvesters is by exploiting the physical principle of kinetics [30, 31].

In this paper, we use a f-TEG, placed around the ankle, to measure the value of harvested power while users are performing activities in the form of sitting at the desk and walking.

Material and Methods

f-TEG module chosen

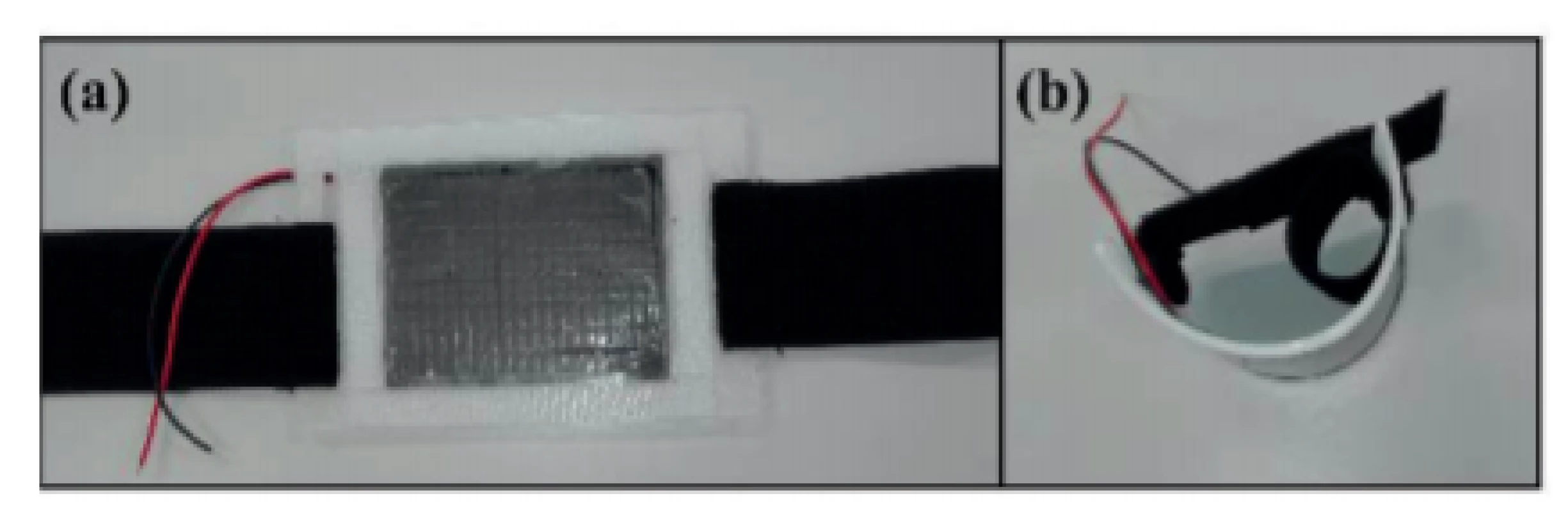

The f-TEG suitable for our aim is the thermoelectric module provided by TEGway, South Korea [32]. It is flexible, thin, light and and comfortable to be worn (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The f-TEG module; TEGway, South Korea. (a) the module in planar position; (b) the module in folded form.

The equation related to the thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT) describes the efficiency of f-TEG, and it is defined as follows:

where: S is the Seebeck coefficient, d is the electrical conductivity, k is the thermal conductivity, and T is the absolute temperature.

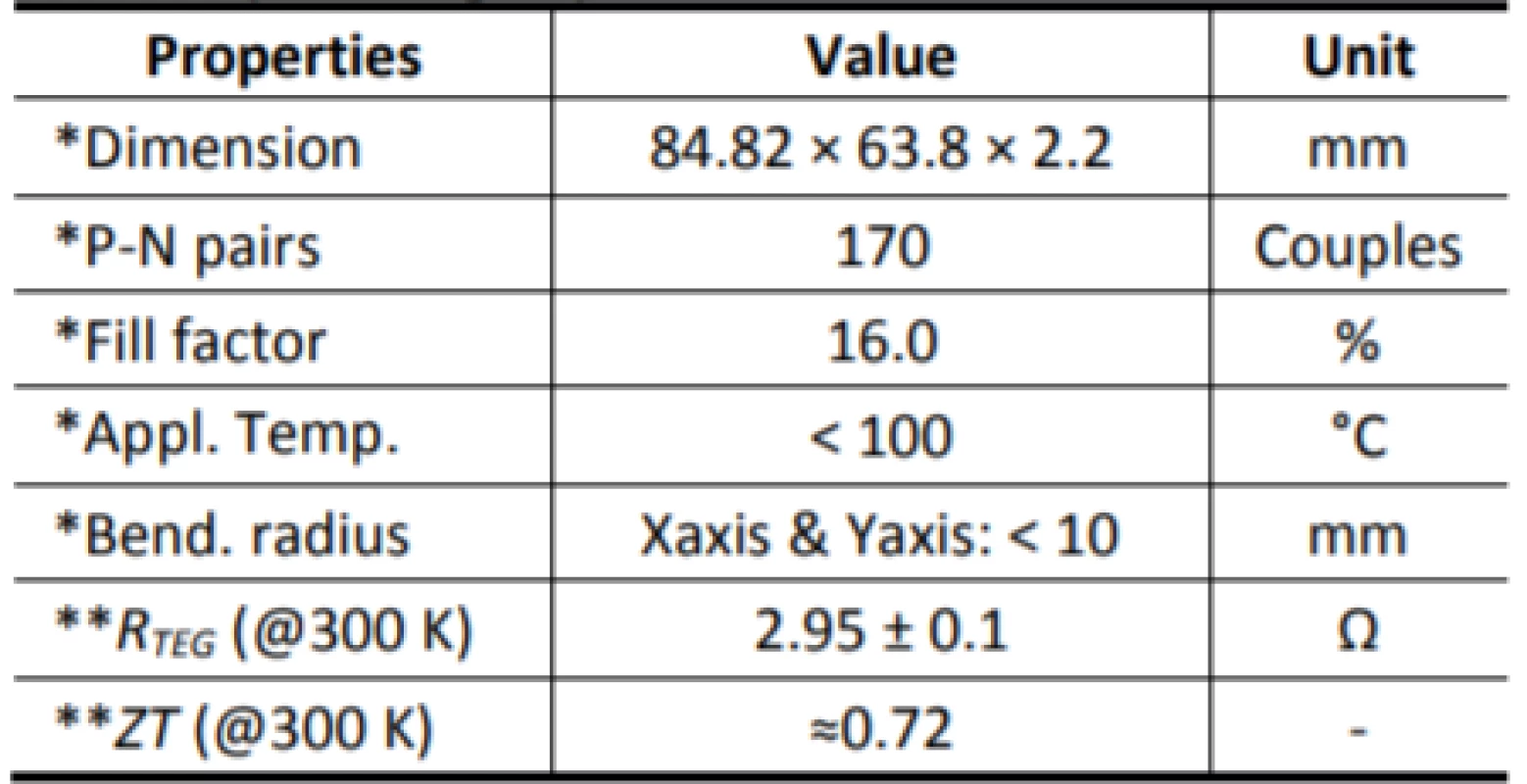

The following Table 1 lists the device and thermo-electric parameters.

Tab. 1. f-TEG specification.

*Device parameters.

**Thermoelectric parameters.As it can be seen in Table 1, the size of the f-TEG module is big. It is due to the flexibility feature of the module that allows a value for the bending radius parameter less than 10 mm. The module encapsulates 170 p-n pairs, and the ZT value is approximately 0.7, which is a similar value compared to that one of rigid TEGs [33]. To increase the power generation of the module, a soft polymer heat sink is designed to be attached to and detached from the f-TEG. Before attaching the heat sink, it must to be wet and squeezed, so that the water would not flow out.

Electrical measurement circuit

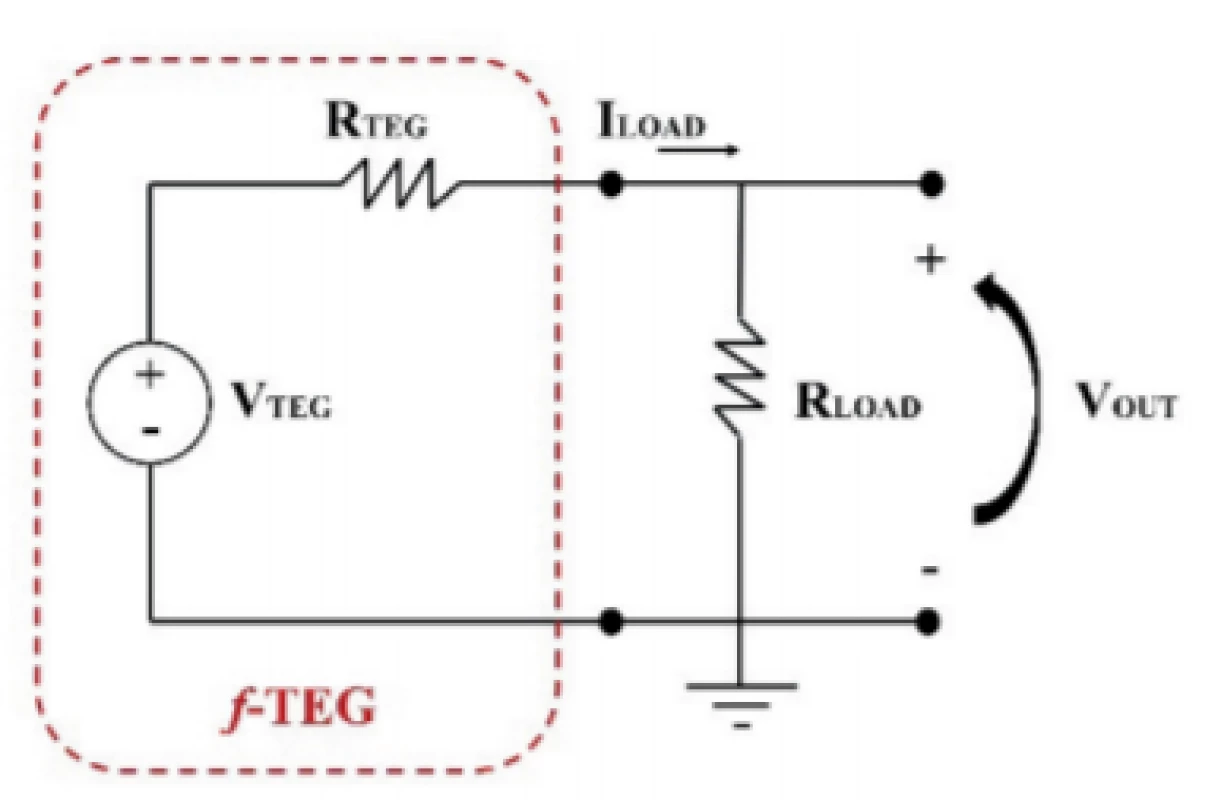

Fig. 2 shows the electrical circuit used for measure-ments.

Fig. 2. Electrical measurement circuit.

The electrical series between the voltage generator and the resistor, RTEG, is the equivalent circuit for the f-TEG module, and the voltage output is measured across a resistor load, RLOAD. The voltage output data were recorder by using the NI USB-9162 DAQ provided by National Instruments, and we used the MATLAB® software for the data visualization and processing. To calculate the f-TEG power output, the following equations explain the relation between the voltage output, VOUT, the resistor load, RLOAD, and the power, PLOAD.

In Eq. (3), it is easy to denote that f-TEG generates the maximum power output when RLOAD is equal to RTEG, i.e. the impedance matching.

To measure the environmental temperature, was used a NTC 10K3MBDI thermistor probe connected to a recording system. The resolution value of sensor is ±0.2 °C, and it has a response time of approximately 400 ms. The temperature sensor was calibrated through a Fluke 1523 reference thermometer.

The chosen on-body position for f-TEG

While performing tests, the f-TEG module was placed around the ankle. It is one of the key points on the body for the placement of wearable devices to acquire biomechanical data for the recognition of ADL [34, 35].

Fig. 3 shows the placement of the f-TEG module plus the soft polymer heat sink at the level of the ankle.

Fig. 3. The f-TEG module placed on the ankle

Testing and Evaluation

Two healthy volunteers (age: 29 ± 2 year; body weight: 75 ± 5 kg; height: 165 ± 5 cm) were recruited to perform the practical experiments.

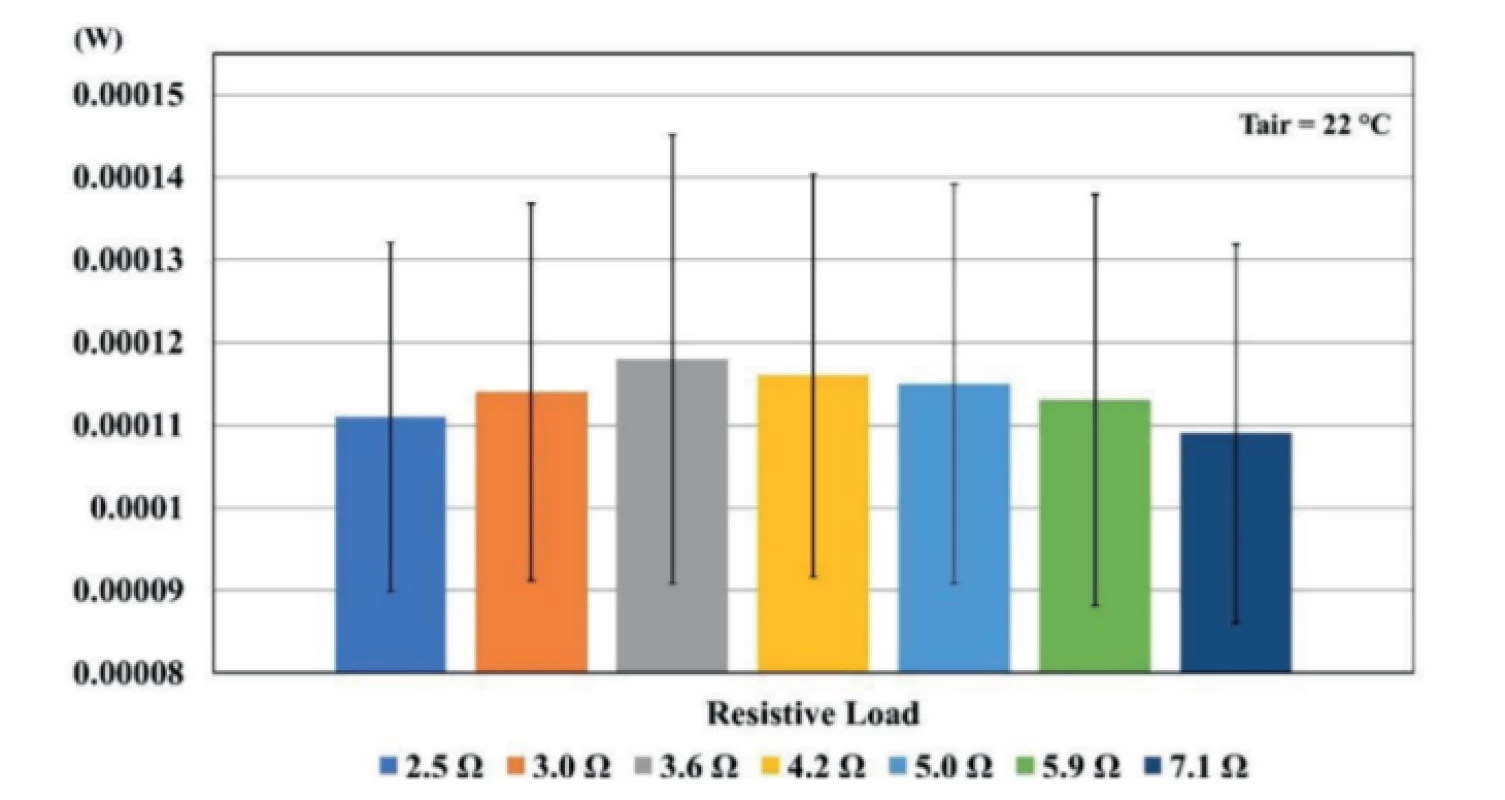

The first stage of measurements was performed to find out the best value of the resistor load that maximizes the power output. The range values of the resistor loads were as follows: [2.5, 3.0, 3.6, 4.2, 5.0, 5.9, 7.1] Ω. The two volunteers were seated at the desk for around an hour, and voltage measurements, for each resistor load, were acquired at the 10th and the 50th minute, respectively. As result, at an environmental temperature of approximately 22 °C, the best values of power output were obtained for the 3.6 Ω resistor load (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The calculated mean values of power output for each value of resistor load. Error bars represent standard deviations.

In the second stage of measurements, we use the 3.6 Ω resistor load in the electrical circuit, and the volunteers performed two ADL in the form of sitting at the desk and walking.

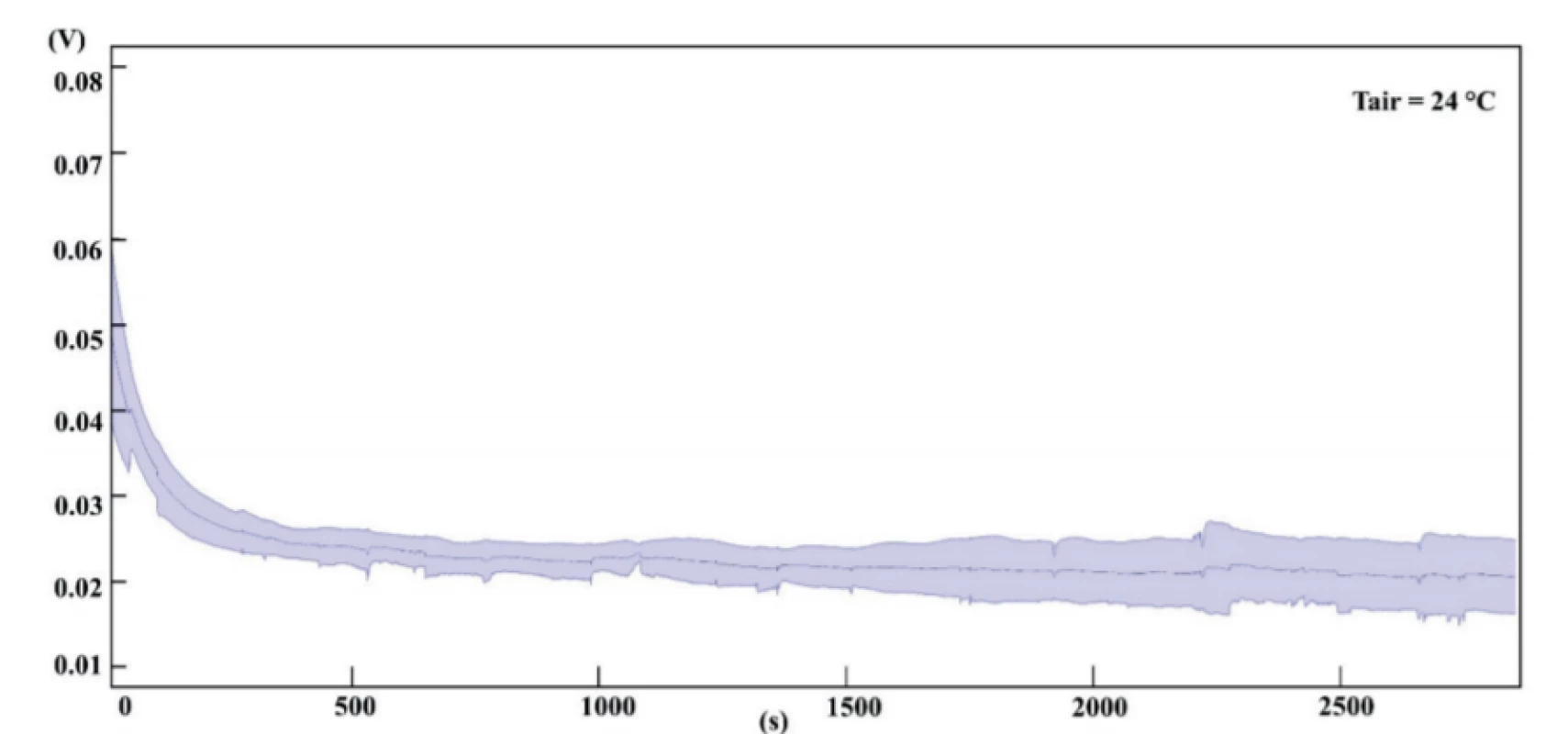

While performing the former, the users were seated for approximately 45 minutes. Fig. 5 shows the mea-sured voltages at an environmental temperature of about 24 °C. In the figure, the middle line is the mean value, while the blue areas around the middle line represent the standard deviations. At the end of test, the voltage output was quite steady around a value of approximately 0.02 V, which implies a power output of 110 µW. In addition, in Fig. 5 it is easy to denote that during the first five minutes, the voltage output decreases rapidly; in that case it is halved from a value of approximately 0.06 V to 0.03 V.

Fig. 5. The measured voltage output when the users were sitting at the desk for approximately 45 minutes.

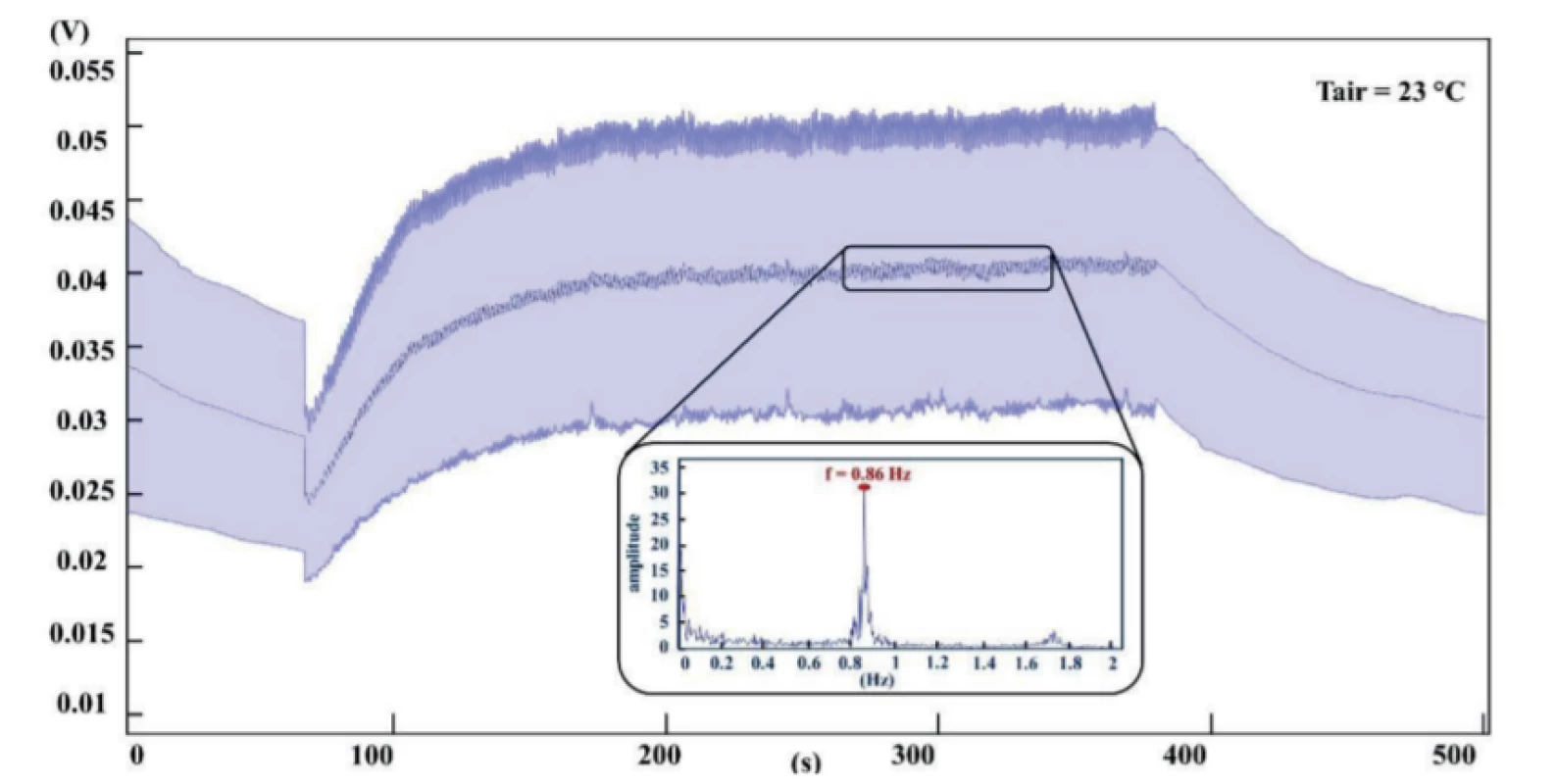

About the latter ADL, the volunteers walked for approximately 5 minutes, after being seated for a brief period. In addition, in the last part of the test the mea-surements quitted after a further sitting period of about 2 minutes. While performing these measurements, the air-temperature was about 23 °C. As result, in Fig. 6 the middle line is the mean value while the areas around it are the standard deviations. While walking, the mea-sured voltage output was approximately 0.04 V, which corresponds to a power output of approximately 450 µW. Moreover, in the inset of Fig. 6, it is clearly visible that the Fourier transform of the calculated mean value shows a frequency peak around the value 0.86 Hz. This value is compatible with usual frequencies of human gait.

Fig. 6. The measured voltage output when the users were walking for approximately 5 minutes. In the inset, the Fourier transform of the signal showing a frequency value of approximately 0.86 Hz.

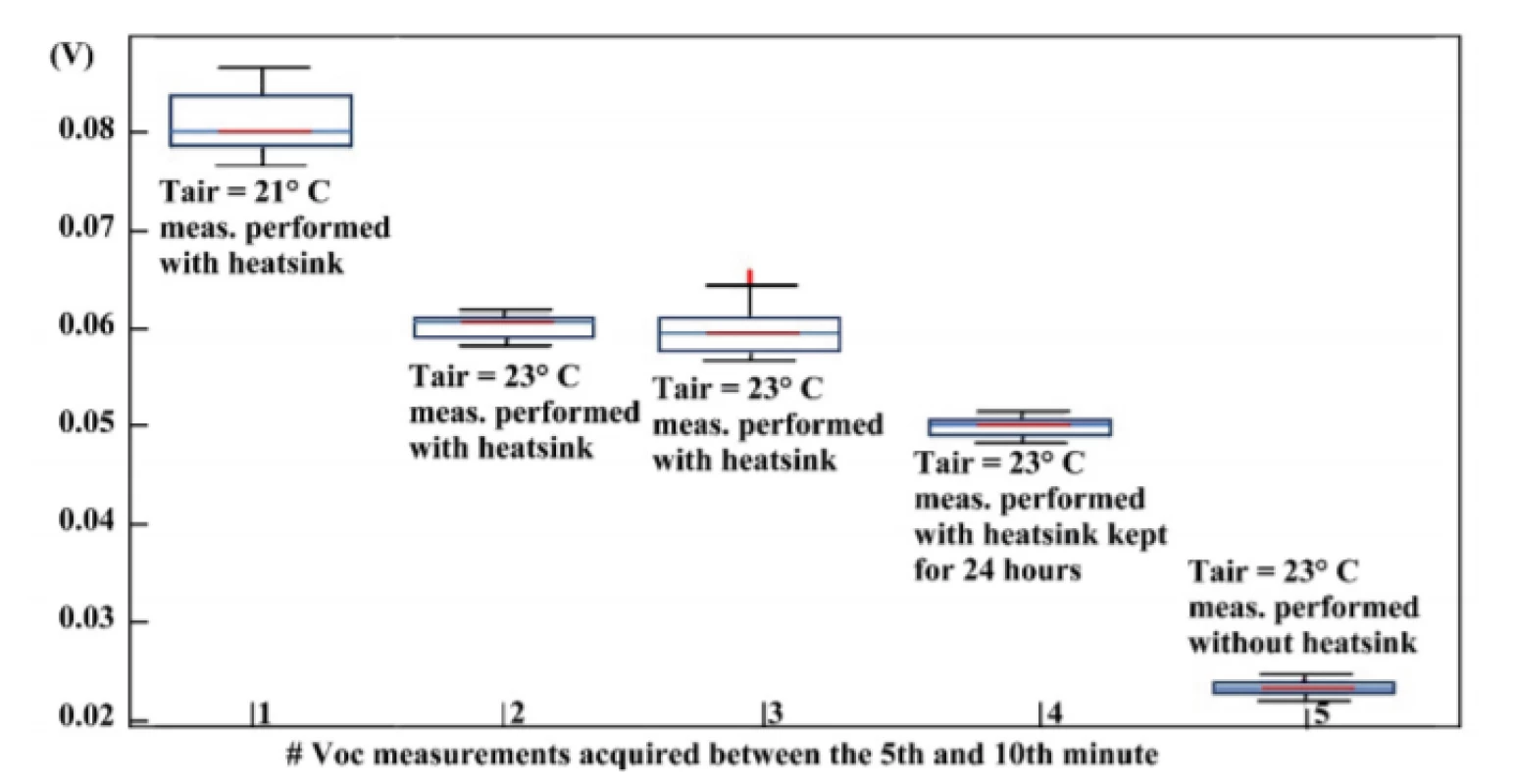

Finally, Fig. 7 shows five measurements of open-circuit voltage, i.e. VOC, acquired between the 5th and the 10th minute of data recording. During these measurements, the users were seated at the desk. In the first one, the air-temperature was 21 °C. In the second and third ones the temperature was 23 °C, but the voltage values were acquired in different days. The fourth measurement is the voltage output at the air-temperature of 23 °C with the heat sink kept for twenty-four hours without to be re-wet. The last measurement is the voltage output measured without using the heat sink, at the air temperature of 23 °C. For these measurements, the best VOC value is obviously the first one: 0.08 V.

Fig. 7. Five measurements of open-circuit voltage, i.e. VOC, acquired between the 5th and the 10th minute of data recording.

Discussions

In the first stage of measurements we found out the value of resistor load that maximizes the f-TEG power output. This value, i.e. 3.6 Ω, differs from the value

shown in Table 1, i.e. 2.95 Ω. It may due to the differ-ence of temperature at the time the measurements were carried out: the TEGway company states a value of 2.95 Ω at 300 K, while our measurements were performed at an environmental temperature of approxi-mately 295 K.

About the ADL in the form of sitting at the desk, the placement of f-TEG on the ankle is not appropriate for harvesting the energy, because the leg activity is almost zero, and the trend of voltage output decreases over the time (Fig. 5).

Conversely, the ADL in the form of walking shows the ability of the f-TEG to generate voltage values appropriate to meet the input voltage requirement of integrated low power DC-DC converters, such as the LTC3108 [36], and EM8900 [37], in which the minimal input voltage is around 20 mV. Moreover, the calculated power output, while users were walking, was approximately 450 ΩW, thus confirming the possibility to use the f-TEG for powering wearable sensor node for the wireless communication of parame-ters. In example, the NFC Dynamic Tag sensor node [38] includes a dynamic NFC/RFID tag, an ultra-low-power µC, a linear regulator power management, an accelerometer, a pressure and a temperature sensor, for a total power consumption less than 1 mW.

Anyway, in connection with a mobile phone, the NFC sensor tag only works with a reading distance of around few centimeters, i.e. 1–10 cm. This constraint does not allow to use the f-TEG on the ankle for pow-ering sensors able to communicate in a continuous way with mobile phones, since they are usually placed in pockets of trousers.

However, as preliminary result shown in the inset of Fig. 6, we found out that the output signal of the f-TEG, while users are walking, is like a sine function with frequency close to that one of human gait [39, 40].

Finally, in the last stage of measurements we ana-lyzed the values of VOC for different environmental temperatures while performing measurements, and as it is well known if the temperature is low, the voltage output will be bigger. In addition, we performed mea-surements with and without heat sink, and we can affirm that the presence of the heat sink is mandatory to meet the requirements of input voltage of a DC-DC converter, which is the first block in a diagram related to an electronic circuit for storing the harvested thermal energy on the body surface.

Conclusions

In this work, a f-TEG was placed at the level of the ankle for measuring the power generated while performing ADL in the form of sitting at the desk and walking. As result, the power output was in the range from 100 to 450 µW. Moreover, while users were walking, the signal output of f-TEG shows a pattern like a sine function with a frequency comparable to that one of human gait. It is only a preliminary result, but the reported statement should encourage the investigation on the field of body thermal energy harvesting to power wearables for the recognition of ADL.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded and promoted by the “Science without borders” action; grant number [CZ.02.2.69/0.0/0.0/16_027/0008463], by the ‘Bio-medical Engineering systems XIV’ project; grant num-ber [SV4508811/2101], by the research project of The Czech Science Foundation (GACR); grant number [17-03037S], and by the Technology Agency of Czech Republic (TACR); grant number [TL01000302].

Ing. Antonino Proto, Ph.D.

Department of Cybernetic and Biomedical Engineering

Faculty of Electrotechnics and Informatics

VSB-TU Ostrava

17. listopadu 15, CZ-708 00

Ostrava-Poruba, Czech Republic

e-mail: antonino.proto@vsb.cz

phone: +420 597 325 818

Zdroje

-

Tricoli, A., Nasiri, N., De, S.: Wearable and miniaturized sensor technologies for personalized and preventive medicine. Advanced Functional Materials, 2017, vol. 27, no. 15, 1605271.

-

Godfrey, A., Hetherington, V., Shum, H., Bonato, P., Lovell, N. H., Stuart, S.: From A to Z: wearable technology explained. Maturitas, 2018, vol. 113, pp. 40–47.

-

Fida, B., Bernabucci, I., Bibbo, D., Conforto, S., Proto, A., Schmid, M.: The effect of window length on the classification of dynamic activities through a single accelerometer. Proceed-ings of the IASTED International Conference Biomedical Engi-neering, 2014, vol. 2325, pp. 123–127.

-

Karchňák, J., Šimšík, D., Siman, D., More, M.: Utilizing of mems sensors in rehabilitation process. Lekar a Technika, 2013, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 28–31.

-

Caramia, C., Bernabucci, I., Conforto, S., De Marchis, C., Proto, A., Schmid, M.: Spatio-temporal gait parameters as estimated from wearable sensors placed at different waist levels. Proceedings of IEEE EMBS Biomedical Engineering and Sciences Conference, 2016, pp. 727–730.

-

Lopot, F.: Wearable artificial kidney – evolution of its concepts and current state-of-the-art. Lekar a Technika, 2013, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 5–12.

-

Fida, B., Proto, A., Bibbo, D., Conforto, S., Bernabucci, I., Schmid, M.: Real time event-based segmentation to classify locomotion activities through a single inertial sensor. Proceed-ings of the 5th EAI International Conference on Wireless Mobile Communication and Healthcare, 2015, pp. 104–107.

-

Stredova, M., Sorfova, M., Socha, V., Kutilek, P.: Biofeedback as a neurobiomechanical aspect of postural function. Lekar a Technika, 2017, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 19–22.

-

Proto, A., Bibbo, D., Conforto, S., Schmid, M. A new micro-controller-based system to optimize the digital conversion of signals originating from load cells built-in into pedals. Pro-ceedings of IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference, 2014, pp. 300–303.

-

Vavrinský, E., Donoval, M., Daricek, M., Horinek, F., Popovic, M., Hanic, M., Jagelka, M.: Monitoring of EMG to force ratio using new designed precise wireless sensor system. Lekar a Technika, 2014, vol. 44, no. 3, 2014, pp. 17–22.

-

Jagelka, M., Jeleň, M., Vavrinský, E., Daříček, M., Donoval, M.: Implementation of pulse oximetry measurement to wireless biosignals probe. Lekar a Technika, 2014, vol. 44, no. 3, 2014, pp. 37–40.

-

Milenković, A., Otto, C., Jovanov, E.: Wireless sensor networks for personal health monitoring: Issues and an implementa-

tion. Computer Communications, 2006, vol. 29, no. 13–14, pp. 2521–2533. -

Vullers, R. J. M., van Schaijk, R., Doms, I., Van Hoof, C., Mertens, R.: Micropower energy harvesting. Solid-State Elec-tronics, 2009, vol. 53, no. 7, pp. 684–693.

-

Zhou, M., Al-Furjan, M. S. H., Zou, J., Liu, W.: A review on heat and mechanical energy harvesting from human – Princi-ples, prototypes and perspectives. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2018, vol. 82, pp. 3582–3609.

-

Proto, A., Penhaker, M., Conforto, S., Schmid, M. Nanogenera-tors for Human Body Energy Harvesting. Trends in Biotechnol-ogy, 2017, vol. 35, no. 7, pp. 610–624.

-

Proto, A., Penhaker, M., Bibbo, D., Vala, D., Conforto, S., Schmid, M.: Measurements of Generated Energy-Electrical Quantities from Locomotion Activities Using Piezoelectric Wearable Sensors for Body Motion Energy Harvesting. Sensors, 2016, vol. 16, no. 4, 524.

-

Proto, A., Bibbo, D., Cerny, M., Vala, D., Kasik, V., Peter, L., Conforto, S., Schmid, M., Penhaker, M.: Thermal energy har-vesting on the bodily surfaces of arms and legs through a wearable thermo-electric generator. Sensors, 2018, vol. 18, no. 6, 1927.

-

Seebeck, T. J.: Magnetic Polarization of Metals and Minerals by Temperature Differences. Treatises of the Royal Academy of Sciences, 1822, 265, 1822–1823.

-

Rajtukova, V., Zivcak, J., Michalikova, M., Toth, T.: Methodol-ogy of thermographic atlas of the human body. Lekar a Tech-nika, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 32–35.

-

Hyland, M., Hunter, H., Liu, J., Veety, E., Vashaee, D.: Wear-able Thermoelectric Generators for human body heat harvesting. Applied Energy, 2016, vol. 182, pp. 518–524.

-

Kishi, M., Nemoto, H., Hamao, T., Yamamoto, M., Sudou, S., Mandai, M., Yamamoto, S.: Micro thermoelectric modules and their application to wristwatches as an energy source. Proceed-ings of the XVIII International Conference on Thermoelectrics (ICT), 1999.

-

https://www.powerwatch.com

-

Torfs, T., Leonov, V., Van Hoof, C., Gyselinckx, B.: Body-heat powered autonomous pulse oximeter. Proceedings of the Con-ference on Sensors, 2006.

-

Leonov, V., Gyselinckx, B., Van Hoof, C., Torfs, T., Yazicioglu, R. F., Vullers, R. J. M., Fiorini, P.: Wearable self-powered wireless devices with thermoelectric energy scaven-gers. Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference & Exhibi-tion on Integration Issues of Miniaturized Systems—MOMS, MOEMS, ICS and Electronic Components (SSI), 2008.

-

Yan, J., Liao, X., Yan, D., Chen, Y.: Review of Micro Thermo-electric Generator. Journal of Microelectromechanical Sys-tems, 2018, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 1–18.

-

Suarez, F., Parekh, D. P., Ladd, C., Vashaee, D., Dickey, M. D., Ozturk, M. C.: Flexible thermoelectric generator using bulk legs and liquid metal interconnects for wearable electronics. Applied Energy, 2017, vol. 202, pp. 736–745.

-

Kim, C. S., Lee, G. S., Choi, H., Kim, Y. J., Yang, H. M., Lim, S. H., Lee, S.-G., Cho, B. J.: Structural design of a flexible thermoelectric power generator for wearable applications. Applied Energy, 2018, vol. 214, pp. 131–138.

-

Deng, F., Qiu, H. B., Chen, J., Wang, L., Wang, B.: Wearable Thermoelectric Power Generators Combined with Flexible Supercapacitor for Low-Power Human Diagnosis Devices. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2017, vol. 64, no. 2, pp. 1477–1485.

-

Thielen, M., Kara, G., Unkovic, I., Majoe, D., Hierold, C.: Thermal Harvesting Potential of the Human Body. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2018, vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 3307–3313.

-

Khalifa, S., Lan, G., Hassan, M., Seneviratne, A., Das, S. K.: HARKE: Human Activity Recognition from Kinetic Energy Harvesting Data in Wearable Devices. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing Volume 17, Issue 6, 1 June 2018, Pages 1353–1368.

-

Proto, A., Fida, B., Bernabucci, I., Bibbo, D., Conforto, S., Schmid, M., Vlach, K., Kasik, V., Penhaker, M.: Wearable PVDF transducer for biomechanical energy harvesting and gait cycle detection. Proceedings of IEEE EMBS Biomedical Engineering and Sciences Conference, 2016, pp. 62–66.

-

http://www.tegway.co

-

Snyder, G. J., Toberer, E. S.: Complex thermoelectric materi-als. Nature Materials, 2008, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 105–114.

-

Attal, F., Mohammed, S., Dedabrishvili, M., Chamroukhi, F., Oukhellou, L., Amirat, Y.: Physical human activity recognition using wearable sensors. Sensors, 2015, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 31314–31338.

-

Yang, J., Wang, S., Chen, N., Chen, X., Shi, P.: Wearable accelerometer based extendable activity recognition system. Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2010, pp. 3641–3647.

-

http://www.analog.com/en/products/ltc3108.html#product-overview

-

http://www.emmicroelectronic.com/products/power-management/pmu-dc-energy-harvesting-controller/em8900

-

https://www.st.com/en/evaluation-tools/steval-smartag1.html

-

Danion, F., Varraine, E., Bonnard, M., Pailhous, J.: Stride vari-ability in human gait: The effect of stride frequency and stride length. Gait and Posture, 2003, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 69–77.

-

Collet, J., Cerny, M., Delporte, L., Noury, N.: Effect of the placement of the inertial sensor on the human motion detection. Lekar a Technika, 2015, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 21–24.

Štítky

Biomedicína

Článek vyšel v časopiseLékař a technika

2018 Číslo 3-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- EFFECT OF SAMPLING RATE ON THE ACCURACY OF MEASUREMENT OF NEONATAL OXYGEN SATURATION EXPOSURE

- BIPHASIC CALCIUM PHOSPHATE SCAFFOLDS DERIVED FROM HYDROTHERMALLY SYNTHESIZED POWDERS

- FLEXIBLE TEG ON THE ANKLE FOR MEASURING THE POWER GENERATED WHILE PERFORMING ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING

- FROM WHITE BOARD TO PATIENT TRACKING SYSTEM IN ANESTHESIA AND BEYOND

- EEG MICROSTATES ANALYSIS IN PATIENTS WITH EPILEPSY

- Lékař a technika

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- EEG MICROSTATES ANALYSIS IN PATIENTS WITH EPILEPSY

- EFFECT OF SAMPLING RATE ON THE ACCURACY OF MEASUREMENT OF NEONATAL OXYGEN SATURATION EXPOSURE

- BIPHASIC CALCIUM PHOSPHATE SCAFFOLDS DERIVED FROM HYDROTHERMALLY SYNTHESIZED POWDERS

- FLEXIBLE TEG ON THE ANKLE FOR MEASURING THE POWER GENERATED WHILE PERFORMING ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Eva Kubala Havrdová, DrSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání