-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaAtkinesin-13A Modulates Cell-Wall Synthesis and Cell Expansion in via the THESEUS1 Pathway

Most of the visible growth of plant organs is driven by cell expansion without associated cell division. As plant cells are encased in cell walls, expansion requires the controlled loosening of the existing cell wall and synthesis of additional wall material. While a number of factors and plant hormones are known that promote cell expansion, what limits this process and thus restricts final cell and organ size is less well understood. Here, we identify a mutant that forms larger flowers because of increased cell expansion. The affected gene encodes a motor protein associated with the microtubule cytoskeleton that causes microtubule break-down and is required for ensuring an even distribution of secretory organelles within cells. Reduced activity of this motor protein triggers the activation of a pathway that detects defects in cell-wall integrity, which in turn leads to the observed increase in cell-wall synthesis and expansion. The Arabidopsis genome encodes another highly similar motor protein, and the combined loss of their activities causes severe defects, including reduced cell expansion. Thus, the two proteins fulfill an essential function in plant cell growth, and their full activity appears to be required to ensure normal cell-wall synthesis and a timely cessation of cell expansion.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Genet 10(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004627

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004627Summary

Most of the visible growth of plant organs is driven by cell expansion without associated cell division. As plant cells are encased in cell walls, expansion requires the controlled loosening of the existing cell wall and synthesis of additional wall material. While a number of factors and plant hormones are known that promote cell expansion, what limits this process and thus restricts final cell and organ size is less well understood. Here, we identify a mutant that forms larger flowers because of increased cell expansion. The affected gene encodes a motor protein associated with the microtubule cytoskeleton that causes microtubule break-down and is required for ensuring an even distribution of secretory organelles within cells. Reduced activity of this motor protein triggers the activation of a pathway that detects defects in cell-wall integrity, which in turn leads to the observed increase in cell-wall synthesis and expansion. The Arabidopsis genome encodes another highly similar motor protein, and the combined loss of their activities causes severe defects, including reduced cell expansion. Thus, the two proteins fulfill an essential function in plant cell growth, and their full activity appears to be required to ensure normal cell-wall synthesis and a timely cessation of cell expansion.

Introduction

Growth of plant lateral organs to their characteristic sizes is based on cell proliferation and on cell expansion [1]. In a first phase of organ growth cells throughout the primordium increase in size and divide mitotically. Cell proliferation then arrests progressively from the tip of the organ towards proximal regions, until all of the cells have ceased dividing and instead continue to grow by post-mitotic cell expansion. Genetic analysis in Antirrhinum majus and Arabidopsis thaliana has identified a number of factors that influence the final number of cells in an organ and thus its size [1]. By contrast, our knowledge about the factors regulating cell expansion in growing lateral organs is more limited [2]. Although it is well established that ploidy correlates with final cell size, the underlying molecular basis remains unclear [2], [3]. Whereas the phytohormones auxin, gibberellins and brassinosteroids can promote cell expansion, ethylene and jasmonic acid inhibit organ growth by affecting cell expansion [4], [5]. Brassinosteroids and gibberellins act via three antagonistic helix-loop-helix nuclear proteins to promote cell expansion [6], [7], and brassinosteroids also act via ARGOS-LIKE [8]. In addition, the TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN (TOR) signalling pathway in plants promotes cell expansion [9], [10], [11]. In petals, a specific isoform of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor BIGPETALp (BPEp) limits cell expansion and thus final petal size, acting downstream of jasmonic acid and in concert with the auxin response factor ARF8 [12], [13], [14].

Plant cells are encased by cell walls composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin that resist the turgor pressure of the cells and thus enable an erect growth habit [15]. For a cell to expand, its wall needs to be loosened in a controlled manner. Expansins are one class of cell wall-loosening factors. Increased or reduced expansin activity leads to larger or smaller organs due to enhanced or reduced cell expansion, respectively [16], [17], [18]. To prevent a progressive thinning of the wall during cell expansion, additional wall material needs to be synthesized and added to the growing wall. While hemicelluloses and pectins are synthesized in the Golgi apparatus, the cellulose microfibrils are produced at the plasma membrane by membrane-localized cellulose synthase (CESA) complexes [15], [19]. In higher plants these are thought to consist of up to 36 subunits drawn from a set of three different isoforms [19]. For example, the isoforms encoded by the CesA1 (At4g32410), CesA3 (At5g05170), and either CesA2, CesA5 or CesA6 (At5g64740) genes form the CESA complex for primary-cell wall synthesis in seedlings [20]. CESA complexes are presumably assembled in the Golgi in an inactive state and are transported to the plasma membrane where they become active [21], [22], [23], [24]. Delivery of CESA complexes to the plasma membrane can occur directly from the Golgi, or via small cytoplasmic compartments [21], [22], [25], to sites that preferentially co-occur with cortical microtubules. Once inserted in the plasma membrane, CESA complexes begin to polymerize cellulose microfibrils, which drives motility of the complexes along cortical microtubules, resulting in an ordered cellulose deposition on the inner face of the cell wall in a pattern that reflects the arrangement of the microtubules [23]. Movement of CESA complexes along microtubules requires POM-POM2/CELLULOSE SYNTHASE INTERACTING1, whose loss of function results in reduced cell expansion, similar to what is also observed for other mutants affecting cell-wall synthesis [26].

Two microtubule-based motors of the kinesin family appear to link the cortical array of microtubules to cell-wall synthesis [27], [28]. The FRAGILE FIBER1 (FRA1) protein, a member of the KIF4 family of kinesins, is required for the ordered deposition of cellulose microfibrils in the walls of interfascicular-fiber cells in the Arabidopsis stem [28]. Mutations in the internal-motor kinesin AtKINESIN-13A (AtKIN13A; At3g16630) lead to the outgrowth of an additional branch in Arabidopsis trichomes; this outgrowth of an extra branch most likely involves additional cell-wall synthesis [27]. The AtKIN13A protein is found in close association with Golgi stacks (and Golgi-derived secretory vesicles in peripheral root cap cells), and loss of its function causes clustering of Golgi stacks in the cell cortex [27], [29]. This suggests that AtKIN13A disperses Golgi stacks along cortical microtubules after they have been transported to the cell cortex via the actomyosin system [27], [30]. As in the fra1 mutant, the distribution and arrangement of cortical microtubules are unchanged in atkin13a mutant leaf cells [27], [30]. Recent work has demonstrated that AtKIN13A has microtubule-depolymerizing activity in vitro and in vivo, and that this activity is required for a normal pattern of secondary cell-wall formation in xylem cells [31], [32]. Loss of AtKIN13A function results in smaller xylem cell-wall pits (i.e. regions free of secondary cell-wall deposition), while overexpression increases pit size, demonstrating that AtKIN13A influences cell-wall deposition in xylem cells. AtKIN13A protein is recruited to the plasma-membrane by interacting with MICROTUBULE DEPLETION DOMAIN1 (MIDD1) via its C-terminal coiled-coil domain; MIDD1 in turn is brought to the plasma membrane via active Rho of plant (ROP) GTPase signalling [31], [32]. However, how the activities of AtKIN13A in depolymerizing microtubules and dispersing Golgi stacks are connected is currently unknown. Based on the opposite trichome phenotypes of atkin13a and angustifolia (an) mutants [33], [34], it has been proposed that trichome branches are initiated at sites of preferential Golgi delivery [30]. AN (At1g01510) encodes a protein of the CtBP/BARS family that localizes to the trans-Golgi network [33], [34], [35]. Loss of AN function causes defects in Golgi-derived vesicles, suggesting that AN functions like BARS as a regulator of endomembrane trafficking.

The integrity of the cell wall during growth is actively monitored by plants [36]. One branch of the cell-wall integrity system comprises transmembrane receptor-like kinases (RLKs) that appear to sense changes in the structure and/or composition of the cell wall or the presence of fragments derived from cell-wall polymers. WALL-ASSOCIATED KINASES (WAKs) bind to pectin in the cell wall, and the WAK2 protein (At1g21270) has been suggested to link cell-wall sensing to the control of turgor pressure and ultimately cell expansion [37], [38], [39]. Three members of the Catharanthus roseus RLK1-LIKE (CrRLK1L) family from Arabidopsis, THESEUS (THE1; At5g54380), HERKULES-KINASE1 (HERK1) and FERONIA have also been implicated in cell-wall integrity sensing [40]. Under conditions of reduced cellulose biosynthesis in seedling hypocotyls, THE1 activity causes increased lignification and limits cell expansion by upregulating the expression of genes encoding cell-wall proteins, such as extensins, and pathogen-defense proteins [41]. By contrast, in wild-type plants THE1 activity is required redundantly with that of HERK1 to promote cell expansion, acting in parallel to the brassinosteroid pathway [42].

How cell expansion is limited to ensure an appropriate final cell and ultimately organ size remains an important open question. Also, the role of the cell wall in restricting final cell size is currently unclear. Therefore, we investigated a novel mutant that causes petal overgrowth due to excess cell expansion. Our results show that defects in cell-wall synthesis due to reduced AtKIN13A activity trigger THE1-dependent signalling, leading to changes in cell wall architecture and enhanced cell expansion. Thus, the structure of the cell wall appears to play an important role in limiting cell expansion during post-mitotic organ growth.

Results

Mutations in AtKINESIN-13A change petal size

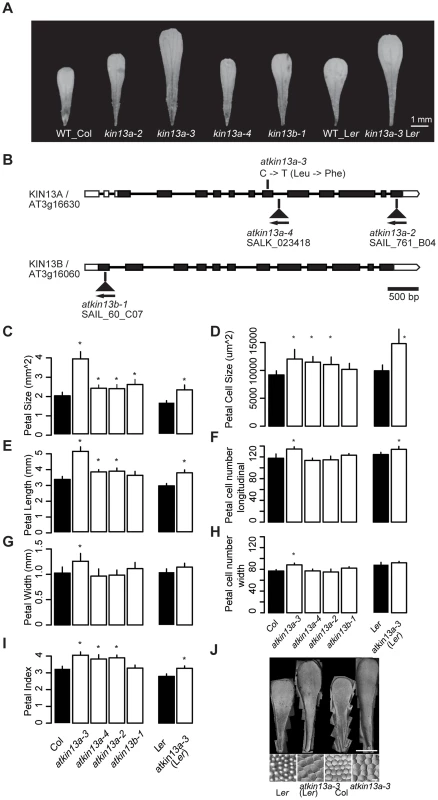

In an EMS-mutagenesis screen in the Landsberg erecta (Ler) background for mutations with altered petal size, we identified a line with larger petals (Fig. 1A). Genetic mapping and sequencing of candidate genes indicated that the mutation affects the AtKINESIN-13A (AtKIN13A; At3g16630) gene (Fig. 1B; Fig. S1). The mutant allele carries an EMS-induced C-to-T transition at position 1000 of the coding sequence, changing a leucine to a phenylalanine. The affected amino acid is part of an invariant Asp-Leu-Leu (DLL) motif in the central motor domain of KIN13 homologues from plant and animal kingdoms (Fig. S2H), suggesting that the mutation interferes with the known microtubule depolymerizing activity of the protein [31], [32]. Two mutant alleles of AtKIN13A carrying T-DNA insertions have previously been described as atkin13a-1 (Salk_047048) and atkin13a-2 (SAIL_761_B04) [27]; therefore, we named the EMS-induced allele atkin13a-3. In addition, we isolated another T-DNA insertion allele from the Salk collection [43] with the insertion in a more 5′ position than in atkin13a-1 and will refer to this as atkin13a-4 (line Salk_023418) (Fig. 1B). We used the atkin13a-2, atkin13a-3, and atkin13a-4 alleles in this study. RT-PCR analysis indicated that atkin13a-3 plants express full-length AtKIN13A mRNA, whereas no full-length transcript can be detected in mutants for the T-DNA insertion allele atkin13a-4 (Fig. S2A).

Fig. 1. Petal phenotypes of atkin13a and atkin13b loss-of-function mutants.

(A) Photographs of petals of the indicated genotypes. Scale bar is 1 mm. (B) Schematic representation of the AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B loci and position of mutant alleles. Open rectangles represent UTRs, filled rectangles show the protein-coding region, and thick connecting lines show introns. (C–I) Measurements of petal parameters for the indicated genotypes. Numbers in C and D indicate relative parameter values with respect to the corresponding wild-type values. Asterisk indicates significant difference from wild-type at p<0.05 (with Bonferroni correction for comparisons to Col-0). (C) Petal size. (D) Petal-cell size. (E) Petal length. (F) Petal cell number in the longitudinal direction. (G) Petal width. (H) Petal cell number along the petal width. (I) Petal index, i.e. length divided by width. (J) Gel prints (top) and representative cells (bottom) from petals of the indicated genotypes. Scale bars are 1 mm (top panel) and 100 µm (bottom panel). Values are mean + SD of 12 petals (C,E–I) or of 50 petal cells each from more than 10 petals (D). We characterized the petal phenotype of the three atkin13a mutant alleles. To be able to better compare the effect of the atkin13a-3 allele to that of the T-DNA insertion alleles in the Col-0 background, we introgressed it into the Col-0 background by four rounds of backcrossing; this line will be referred to as atkin13a-3C. The atkin13a-3 allele leads to enlarged petals in both Ler and Col-0 backgrounds (Fig. 1A,C). Length and width is similarly enlarged in the Ler background, while in the Col-0 background petal length is more strongly affected, leading to an increased petal index (the ratio of length to width) as a description of petal shape (Fig. 1C,E,G,I). At the cellular level, cell numbers along the length and width directions of the petal are significantly, albeit weakly increased in atkin13a-3 mutants, more strongly in the Col-0 introgression line (Fig. 1F,H), possibly reflecting the activity of accession-specific modifiers. More importantly, petal-cell size is significantly enlarged in the mutant, and in particular in the Ler background the excess cell expansion accounts for essentially all of the overall increase in petal size (Fig. 1D,J). Measuring cell lengths along the petal in atkin13a-3C mutants indicates that cells are longer in the mutant than in wild type (Fig. S2B–D). The atkin13a-3 allele behaves in a semi-dominant manner regarding petal size, with heterozygotes showing an intermediate increase in petal area relative to wild-type and homozygous mutant plants (Fig. S2E). In the T-DNA insertion mutants, petal size and petal length are also increased, albeit to a lesser extent (Fig. 1C,E). This results in an increased petal index, reflecting the narrower shape of the organs (Fig. 1A,E,I). Petal cell number is not significantly changed in the insertion mutants relative to wild type (Fig. 1F,H), yet petal cells in the lobe region are larger and longer (Fig. 1D, Fig. S2C,D).

Previous work has shown that atkin13a-1 and atkin13a-2 mutants form trichomes with more than the usual three branches [27]. Similarly, overbranched trichomes are observed in atkin13a-3 and atkin13a-4 mutants (Fig. S2F,G).

To determine whether the effects seen in the atkin13a-3 and the atkin13a-4 mutants are indeed the consequence of a loss of AtKIN13A function, we transformed a wild-type version of the gene into the homozygous mutants and tested for complementation of the phenotype. Trichome branching, petal size and petal-cell size were fully rescued in transformants in the atkin13a-4 background (Fig. S3A–C). While transformants in the atkin13a-3 background still formed significantly, albeit only slightly larger petals than wild type, their petal-cell size and trichome branching were fully rescued (Fig. S2A–C). The failure to completely rescue petal size likely reflects the semi-dominant nature of the atkin13a-3 allele (see Discussion).

Thus, AtKIN13A function is required to limit cell expansion (and to a small degree also cell proliferation) in growing petals. The semi-dominant behaviour of the atkin13a-3 allele suggests that the mutant protein that is most likely still produced from this allele acts as a dominant-negative form that interferes with the function of wild-type AtKIN13A and possibly other, closely related kinesins (see below).

AtKIN13A function is required in late stages of petal growth to limit cell expansion

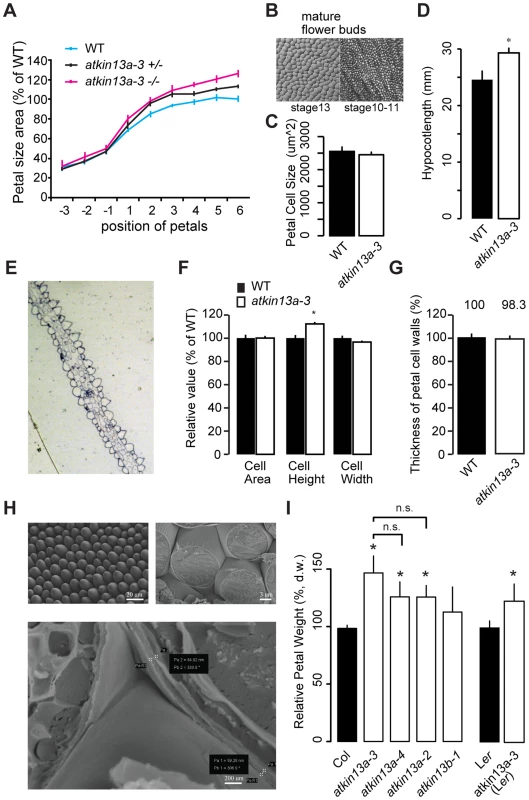

The strong effect of the atkin13a-3 mutation on petal-cell size prompted us to ask whether cell enlargement results from a decoupling of cell growth and cell division already in early stages of petal development, or whether the excess cell enlargement is only seen during the phase of postmitotic cell expansion. A comparison of petal-cell sizes from stage 10–11 petals shows no difference between atkin13a-3 and wild-type petals (Fig. 2B,C). Similarly, following petal growth from the third-oldest unopened flower bud through to fully mature flowers indicates that petal size of the atkin13a-3 mutant only deviates from wild type shortly before the flower opens up via strong expansion of petal cells (Fig. 2A). Thus, together these results suggest that AtKIN13A function is mainly required in the late phase of postmitotic cell expansion towards the end of petal growth to limit cell size.

Fig. 2. Increased postmitotic cell expansion in atkin13a mutants.

(A) Developmental series of petal size for the indicated genotypes. Flower 1 represents the youngest open flower, while flower −1 is the oldest unopened flower bud. Values are normalized to the size of the wild-type petals from the oldest measured flowers. Values represent mean ± SEM (n<10 petals). (B) Gel-print images of wild-type petal cells from the indicated flower stages (after [71]). (C) Petal-cell size from stage 10–11 buds is not different between wild type and atkin13a-3 mutants. Values are mean ± SD of 50 petal cells each from more than 6 petals. (D) Etiolated hypocotyls are longer in atkin13a-3 mutants than in wild type. Values are mean ±SD of 10 plants. 8-day old seedlings were measured. (E) Toluidine-blue stained cross section through a mature wild-type (left) and a mature mutant petal (right). Adaxial side is to the right in both images. (F) Cross-sectional cell area, cell height and cell width from petals of wild type and atkin13a-3EMS mutants. Values are normalized to wild-type values and represent mean ± SD of 50 petal cells. (G) Thickness of petal-cell walls as measured from scanning-electron micrographs. Values are mean ± SEM of 100 petal cells from 10 petals, normalized to the wild-type value. (H) Scanning-electron micrographs of wild-type petals before (top left) and after (top right and bottom) freeze fracturing. Bottom image also indicates how measurements of cell-wall thickness were taken (pairs of white crosses). Length of scale bars is indicated. (I) Petal dry weight of the indicated genotypes. Values are mean + SD from 3 replicates of 50 petals each, normalized to the respective wild-type values. Differences between the three atkin13a mutant alleles are not statistically significant (n.s.). Asterisk indicates significant difference from wild-type at p<0.05 (with Bonferroni correction where appropriate). The measurements of petal-cell sizes above were taken from gel-prints of petals and thus represent a measure of the two-dimensional ‘ground area’ of the cells [44]. To determine whether the cells in the atkin13a-3 mutant are indeed larger in volume or whether it is merely their shape that has changed to a more flattened one despite a wild-type cell volume, we prepared transverse cross-sections through atkin13a-3 mutant and wild-type petals and measured the average area, height and width of the conical cells in the petal lobe (Fig. 2E). The average height of atkin13a-3 mutant petal cells was increased, while their width was slightly decreased compared to wild type; this results in the same cross-sectional area as in wild type (Fig. 2F), indicating that atkin13a-3 mutant petal-cells are indeed larger in volume than wild-type cells. This result was further confirmed by measuring cell heights from confocal-microscopy images (Fig. S4C).

To determine whether at the cellular level the increased expansion is accompanied by more cell-wall synthesis or whether the same amount of cell-wall material is stretched out more thinly in the atkin13a-3 mutant compared to wild type, we measured the thickness of the cell wall in cells of the petal lobe using two approaches. Firstly, we freeze-fractured petals to expose the lateral walls of the conical petal cells and measured the thickness of the walls using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 2G,H). Secondly, the transverse sections through the petal lobes (see above) were imaged using transmission electron microscopy, and the thickness of the cell walls at the base was measured. Both methods indicated that cell-wall thickness in the mutants was indistinguishable from that in the wild type, suggesting that mutant petal cells synthesize more cell-wall material that is stretched out to the same final thickness as in wild type (Fig. 2G; Fig. S4A,B). Increased synthesis of dry matter, much of which is cell-wall material [45], was also evident when comparing wild-type and atkin13a mutant petals (Fig. 2I). Dry weights correlated closely with overall petal area, with the strongest increase in atkin13a-3 and lesser increases in the other two alleles (Fig. 1C, 2I).

To ask whether the increased cell expansion in atkin13a-3 mutants is specific to petals, we determined the sizes of mesophyll cells in leaves. Mutants for atkin13a formed larger, yet fewer leaf cells (Supplemental Figure S3D), indicating that AtKIN13A function also limits cell expansion in leaves. In addition, atkin13a-3 mutants formed longer hypocotyls in the dark (Fig. 2D). Hypocotyl elongation during etiolation relies exclusively on post-mitotic cell expansion [46], indicating that also in this situation AtKIN13A function is required to prevent excess cell expansion. Given the well-established relationship between cell size and ploidy levels [3], we asked whether the excess cell expansion in the mutant petals resulted from ectopic endoreduplication. However, flow cytometry on petal cells indicated no difference in ploidy levels (Fig. S4E).

Thus, atkin13a-3 mutant petal cells deposit more cell-wall material, accompanied by excess cell expansion to a larger final volume without any increase in ploidy levels.

AtKIN13A interacts genetically with AN

To place AtKIN13A in genetic-interaction networks, we generated double mutants between atkin13a and other mutants showing a defect in cell expansion and/or petal growth [47], [48], [49]. Double mutants of atkin13a-3 and ethylene insensitive2 (ein2), brassinosteroid insensitive1 (bri1) or rotundifolia3 (rot3; a mutant with reduced, but not abolished levels of active brassinosteroids; [50]), showed essentially additive phenotypes regarding their petal sizes (Fig. S5A–C), suggesting that AtKIN13A acts independently of ethylene and brassinosteroids.

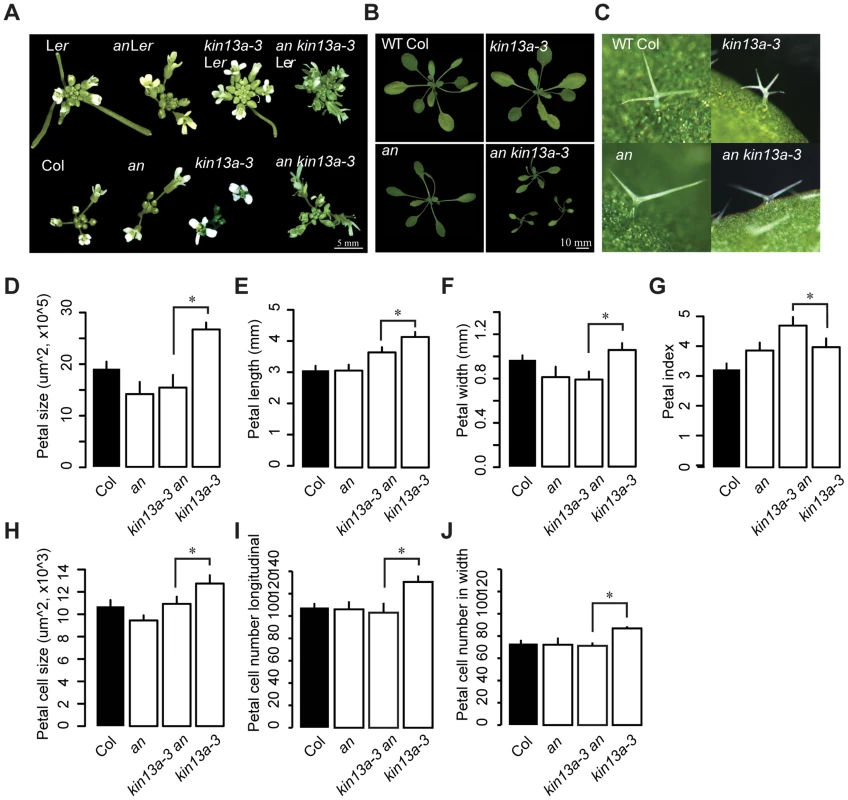

The an atkin13a-3 double mutant showed a novel phenotype not observed in either single mutant. Double mutant rosettes are smaller than in either single mutant (Fig. 3B). The inflorescences have a tousled appearance, with an unordered arrangement of floral organs (Fig. 3A). Petals of the double mutant had the same area as an single mutant petals, yet their shape was longer and narrower than in either single mutant (Fig. 3D–G). While the increase in petal-cell numbers observed in atkin13a-3 mutants is suppressed by introducing the an mutation, the size of double mutant petal cells was intermediate between that of the single mutants (Fig. 3H–J). Regarding trichome branching, the an mutation is epistatic over atkin13a-3, with double mutants forming only two-branched trichomes (Fig. 3C). Thus, an and atkin13a-3 show a non-additive interaction in several respects, with the double mutant presenting a synergistic (e.g. rosette growth, inflorescence organisation) or epistatic phenotype (e.g. trichome branching) in different processes. This suggests that at least in these processes AN and AtKIN13A interact to control cell growth via their effects on Golgi function.

Fig. 3. Genetic interaction between an and atkin13A.

(A) Photographs of inflorescences of the indicated genotypes. As the atkin13a-3 mutant is from the Ler background and an-1 from the Col-0 background, double and single mutants were selected either with (top row) or without functional ERECTA (bottom row). Scale bar is 5 mm. (B) Photographs of rosettes Scale bar is 10 mm. (C) Photographs of leaf trichomes of the indicated genotypes. (D–J) Measurements of petal parameters for the indicated genotypes. (D) Petal size. (E) Petal length. (F) Petal width. (G) Petal index, i.e. length divided by width. (H) Petal-cell size. (I) Petal cell number in the longitudinal direction. (J) Petal cell number along the petal width. Values are mean ± SD of 12 petals from more than 8 plants (A–F,H,I) or of 50 petal cells from more than 8 petals (G). Asterisk indicates significant difference at p<0.05. The THESEUS-dependent cell-wall integrity pathway is activated in atkin13a mutants, resulting in increased cell expansion

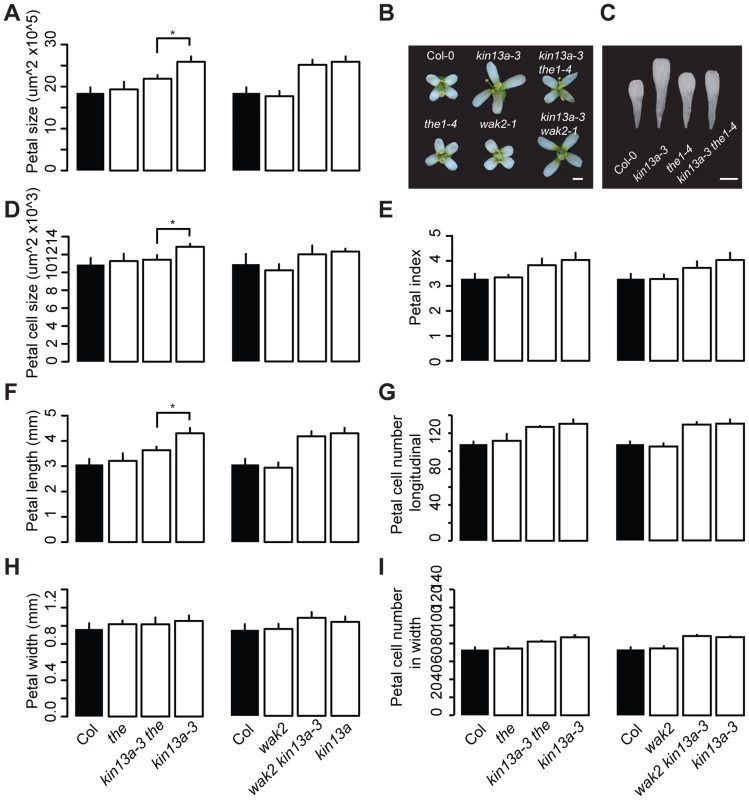

The above results indicate that the increased cell expansion in atkin13a mutant petals is accompanied by increased synthesis of cell-wall material. We wondered how a defect in this kinesin could cause increased cell-wall deposition, especially in light of its known role in microtubule depolymerization and ensuring a uniform distribution of Golgi stacks in the cells [27], [29]. One possibility is that a spatially less uniform cell-wall deposition in atkin13a mutants is perceived by cell-wall integrity sensing, and that this secondarily causes an upregulation of cell-wall synthesis and increased cell expansion. To test this idea, double mutants were analyzed between atkin13a-3C and the1-4 or wak2-1 mutants [38], [41], [42]. Based on published work, both the wak2-1 and the the1-4 alleles represent likely null-mutant alleles, from which no full-length mRNA can be detected [38], [42], making them suitable for epistasis analysis. When grown on soil, neither the wak2-1 nor the the1-4 single mutants have any morphological phenotypes at the whole-plant [38], [42] or the flower level (Fig. 4). The atkin13a-3C wak2 double mutant was very similar to atkin13a-3C single mutants with respect to petal area, cell number and cell size, suggesting that petal overgrowth in atkin13a-3C does not require WAK2 activity (Fig. 4A,B,D–I). By contrast, petal size of the atkin13a-3C the1-4 double mutant was significantly smaller than that of the atkin13a-3C single mutant (Fig. 4A–C). At the cellular level, cell numbers in double mutant petals along the length and width directions are similar to the atkin13a-3C single mutant (Fig. 4F–I); by contrast, the increased cell expansion is entirely suppressed in the double mutant, with cell sizes indistinguishable between the1-4 single and the double mutant (Fig. 4D). This indicates that THE1 activity is required for the increased cell size in atkin13a mutants, suggesting that activation of the THE1-dependent cell-wall integrity pathway triggers the increased cell-wall synthesis and cell expansion as a secondary consequence of an unknown initial cell wall-related defect due to the atkin13a mutation.

Fig. 4. Excess cell expansion in atkin13a mutants requires THE1 activity.

(A,D–I) Measurements of petal parameters for the indicated genotypes. (A) Petal size. (B) Whole-flower photographs of the indicated genotypes. (C) Photographs of petals of the indicated genotypes. Scale bars are 1 mm in (B,C). (D) Petal-cell size. (E) Petal index, i.e. length divided by width. (F) Petal length. (G) Petal cell number in the longitudinal direction. (H) Petal width. (I) Petal cell number along the petal width. Values are mean ± SD of more than 12 petals from 8 plants (A,E–I) or of 50 petal cells from more than 8 petals (D). Asterisk indicates significant difference at p<0.05. Cell-wall structure is changed in atkin13a mutants as a result of THE1 activation

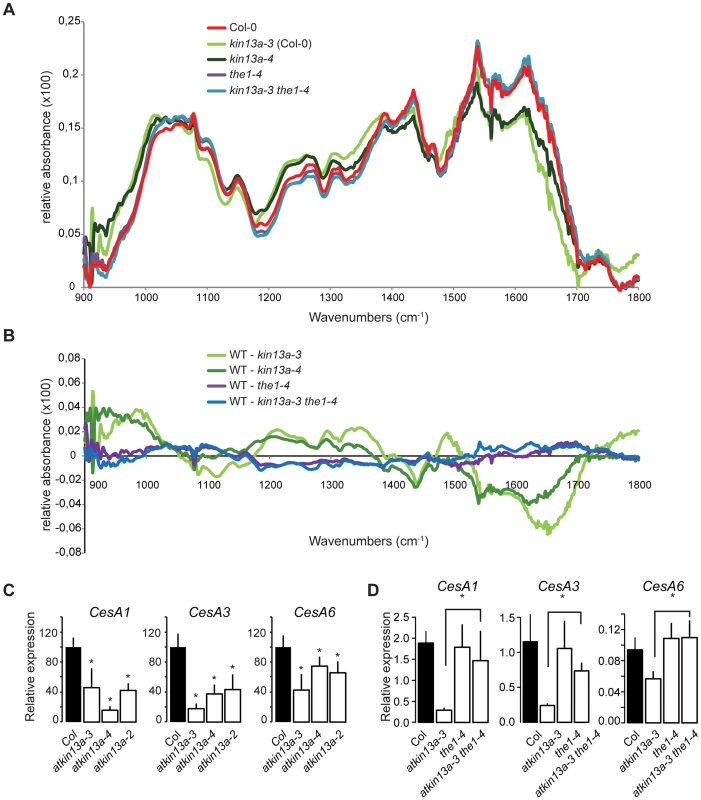

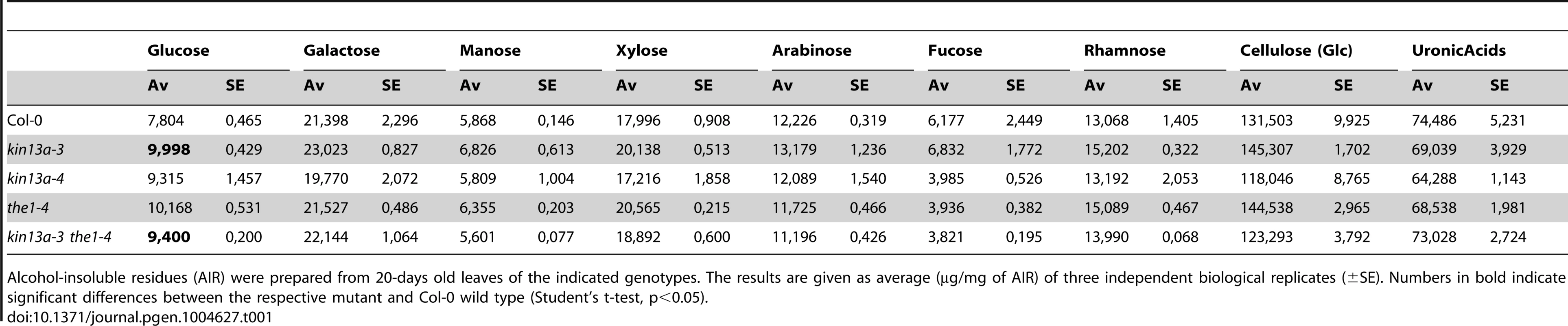

To test whether in addition to the amount of cell-wall material its composition was also changed in atkin13a mutants, we analyzed cell-wall structure and composition by Fourier-transformed infrared-spectroscopy (FTIR) and biochemical profiling of cell-wall monosaccharides. As the latter requires a larger amount of dried wall material than can feasibly be obtained from petals, we performed these analyses using leaf material. As shown above, leaf cells are similarly enlarged in atkin13a mutants, allowing us to use leaves as meaningful proxies for petals for the cell-wall assays. We analyzed two independent atkin13a mutant alleles in the Col-0 background (atkin13a-3C and atkin13a-4), the1-4 single and atkin13a-3C the1-4 double mutants. FTIR was performed on purified cell-wall preparations. Both independent atkin13a mutant alleles showed a very similar difference compared to the wild type, with higher signals in the range from 920 to 1050 cm−1 and much lower signals in the range from 1550 to 1700 cm−1 (Fig. 5A,B, Fig. S6A,B). Comparing the the1-4 single and atkin13a-3C the1-4 double mutants revealed an almost indistinguishable FTIR profile that was very similar to that of the Col-0 wild type, demonstrating complete epistasis of the the1-4 mutation. Biochemical profiling of monosaccharides after cell-wall hydrolysis did not show significant differences between the five tested genotypes, except for higher non-cellulosic glucose levels in atkin13a-3C single and atkin13a-3C the1-4 double mutants (Table 1). To determine whether the organization of the cell wall was affected, petals from unopened flowers (stage 10–11) were stained with Pontamine Fast Scarlet 4B [51] as described in [52] to visualize cellulose microfibrils (Fig. S7). In most of the petal cells we were unable to discern any clear microfibrils, possibly due to background signals from hemicelluloses and/or the nature of petal-cell walls. No clear differences in the staining patterns between wild-type and mutant petals were detectable (Fig. S7).

Fig. 5. Cell-wall composition is altered in atkin13a mutants.

(A) Average Fourier-Transformed-Infrared (FTIR) spectra of three independent biological replicates of the indicated genotypes. (B) Difference spectra obtained by digital subtraction of the average spectra of the indicated genotypes from the Col-0 average spectrum. (C,D) Expression of genes encoding CesA subunits required for primary-cell wall formation in the indicated atkin13a mutant alleles (C) and in single and double mutants of atkin13a-3 and the1-4 (D). Values are mean + SD of three biological replicates. Asterisk indicates significant difference from wild-type at p<0.05 (with Bonferroni correction). Tab. 1. Monosaccharide composition of cell walls from 20-days old leaves.

Alcohol-insoluble residues (AIR) were prepared from 20-days old leaves of the indicated genotypes. The results are given as average (µg/mg of AIR) of three independent biological replicates (±SE). Numbers in bold indicate significant differences between the respective mutant and Col-0 wild type (Student's t-test, p<0.05). Supporting an effect of the atkin13a mutations on cell-wall structure, the expression of the CesA1, CesA3, and CesA6 genes encoding primary cell wall CesA subunits was strongly reduced in atkin13a mutant inflorescences compared to wild type (Fig. 5C). To determine whether also these gene-expression phenotypes of atkin13a mutants are dependent on activation of the THE1-dependent pathway, we assessed expression of the CesA genes in the1-4 single and atkin13a-3 the1-4 double mutants. Expression of all three genes was very similar in the1-4 single mutants compared to wild type (Fig. 5D). Also, expression of the CesA subunit genes is not significantly different between the1-4 single and the1-4 atkin13a-3 double mutants (Fig. 5D), but is significantly higher in the double mutants than in the atkin13a-3 single mutant. This suggests that the reduction of CesA gene expression in atkin13a mutants results to a large extent, if not entirely, from activation of the THE1 pathway.

By contrast, the the1-4 mutation does not rescue the trichome-overbranching phenotype of the atkin13a mutant, despite detectable expression of THE1 in trichomes based on publicly available microarray data (Fig. S6C; http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi; [53]).

Thus, the structure of the cell wall, though not its overall biochemical composition, appears to be affected by alterations in AtKIN13A activity. Reduced activity triggers signalling via the THE1 pathway, resulting in the modified cell-wall structure and increased cell expansion.

AtKIN13A and its close homologue AtKIN13B are redundantly required to promote cell expansion

The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains a closely related gene to AtKIN13A, termed AtKIN13B (At3g16060). This locus codes for a protein with 62% identity/74% similarity to AtKIN13A in the internal motor domain and 58% identity/82% similarity to AtKIN13A in a region of 84 amino acids at the very C-terminal end of the proteins. Based on publicly available gene expression information, both genes show a very similar gene expression pattern, including expression in trichomes (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi; [53]). To determine whether AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B fulfill similar functions in plant growth, we isolated a T-DNA insertion in AtKIN13B, termed atkin13b-1 (SAIL_60_C07) (Fig. 1B). No full-length transcript is detectable in homozygous mutants (Fig. S2A). Plants with the atkin13b-1 mutation also form significantly larger petals, with cell size tending to be larger than wild type, even though this difference is not statistically significant; however, in contrast to atkin13a mutants, petal shape of atkin13b-1 mutants is not affected, as indicated by the unchanged petal index (Fig. 1A,C,I). The size of leaf-mesophyll cells was also increased in atkin13b-1 mutants (Fig. S4D). However, in contrast to atkin13a mutants, these plants do not form overbranched trichomes (Fig. S2F).

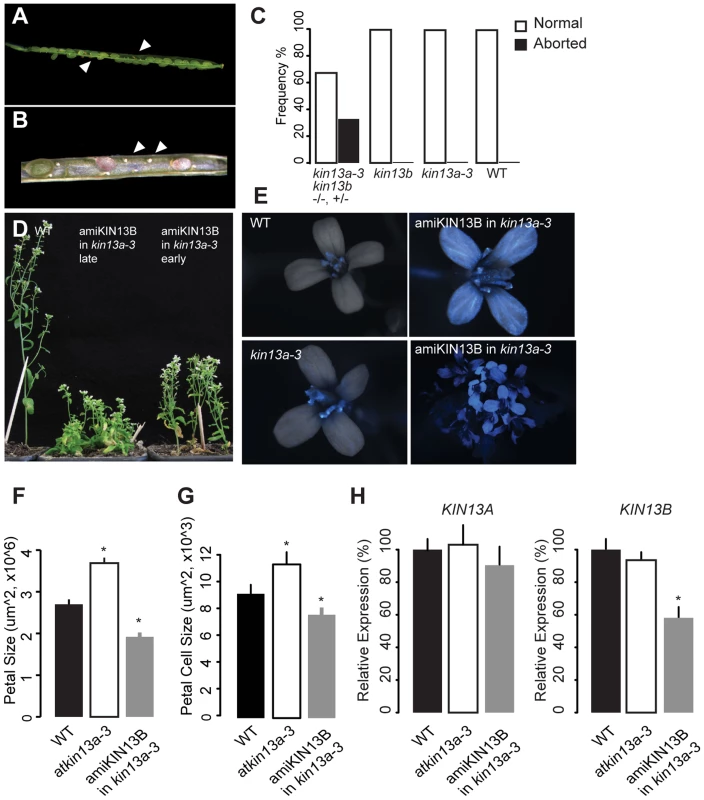

AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B code for similar proteins, raising the possibility that they might act redundantly. To test this, we sought to generate plants lacking the activity of both genes. The two loci are tightly linked on chromosome 3, separated by approximately 210 kb. Therefore, in the progeny of atkin13a-3 +/+ atkin13b-1 transheterozygous plants, we searched for recombinant chromosomes carrying the mutant alleles at both loci by screening for plants that are homozygous mutant for one and heterozygous for the other locus. Out of more than 1000 progeny plants, one atkin13a-3 +/atkin13a-3 atkin13b-1 plant was identified. Amongst its progeny, however, no doubly homozygous mutant could be identified; instead, in the siliques of atkin13a-3 +/atkin13a-3 atkin13b-1 plants many ovules were not fertilized, and of the developing seeds over 25% were brown and shrivelled, indicative of both a gametophytic defect and embryo lethality (Fig. 6A,B). Thus, AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B indeed seem to act redundantly and to fulfil an essential function for gametophyte and early plant development.

Fig. 6. Redundant function of AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B.

(A,B) Lower-magnification (A) and higher-magnification view of opened siliques of an atkin13a-3 +/atkin13a-3 atkin13b-1 plant to show seed abortion (arrowheads in (A)) and unfertilized ovules (arrows in (B)). (C) Quantification of seed abortion. Values are based on more than 100 seeds per genotype. (D) Whole-plant photographs of the indicated genotypes after EtOH-induction before (early) and during bolting (late). (E) Overlays of light and CFP fluorescence micrographs of flowers from the indicated genotypes after EtOH-induction. CFP fluorescence indicates expression of the amiRNA transgene. The two images on the right show a single flower and an overview of an inflorescence from an amiKIN13B-expressing atkin13a-3 mutant plant. (F) Petal sizes of indicated genotypes. Values are mean ±SD of 12 petals from more than 8 plants. (G) Petal-cell sizes of the indicted genotypes. Values are mean ± SD of 50 petal cells from more than 16 petals. (H) Relative expression of AtKIN13A (left) and AtKIN13B (right) in plants of the indicated genotypes after EtOH induction. Values are mean ± SD of three technical replicates. A biological replicate experiment is shown in Fig. S8D. Asterisk indicates significant difference from wild-type at p<0.05 (with Bonferroni correction). As an alternative approach to characterizing the effects of combined AtKIN13 loss of function, a construct for AlcR/AlcA-mediated EtOH-inducible expression of an artificial microRNA (amiRNA) against AtKIN13B was introduced into the atkin13a-3 background, and an analogous construct expressing an amiRNA against AtKIN13A was introduced into atkin13b-1 mutants [54], [55]. For both constructs, EtOH-induction can be monitored with a linked AlcA::CFP reporter gene on the same T-DNA (35S::AlcR—AlcA::miRNA—AlcA::CFP; Fig. 6E, Fig. S8A). Inducing expression of the amiRNA before and during bolting results in reduced stem elongation (Fig. 6D). Similarly, amiRNA expression during flower development leads to the formation of smaller petals due to reduced cell expansion (Fig. 6F,G, Fig. S8B). Successful downregulation of the target mRNA was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6H).

Thus, together these observations indicate that the two related AtKIN13 proteins are essential for normal cell expansion. They also suggest that while a moderate reduction in AtKIN13 function triggers excess cell enlargement, a stronger reduction causes more severe defects in cell development, resulting in reduced cell expansion and ultimately gametophyte and embryo lethality.

Discussion

AtKIN13 activity is essential for plant growth

AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B encode internal-motor kinesins that associate with microtubules [27], [56]. AtKIN13A has been demonstrated to depolymerize microtubules both in vitro and in vivo, and this activity depends on its motor domain [31], [32]. Consistent with this, the strong mutant phenotype seen in the atkin13a-3 allele results from an amino-acid exchange in a highly conserved motif in the central motor domain (Fig. 1; Fig. S1). This mutation behaves in a semi-dominant manner and causes a more severe phenotype than what is observed in available T-DNA insertion lines. Animal kinesin-13 proteins act as dimers to depolymerize microtubules, with dimerization mediated by their N-terminal and coiled-coil domains [57], [58]; thus, a plausible explanation for the stronger phenotype than in the T-DNA insertion lines is that the mutated protein behaves in a dominant-negative manner by binding to wild-type AtKIN13A (in heterozygous plants) or AtKIN13B protein molecules (in atkin13a-3 homozygous mutants) and inactivating the resulting dimers, or by blocking access of AtKIN13B dimers to microtubule ends in atkin13a-3 homozygous mutants. This notion assumes that the two proteins share the same microtubule depolymerization activity, and are targeted to the same subcellular regions, such that in an atkin13a knock-out mutant the AtKIN13B protein takes over a large part of its function, leading to only a subtle phenotype. While not yet demonstrated experimentally, we believe this is a plausible assumption, as both protein domains with a known function (the internal motor domain and the C-terminal region that encompasses the coiled-coil domain and the region binding to MIDD1; [56], [58]) are very similar between AtKIN13A and AtKIN13B proteins, suggesting they have the same molecular function, can heterodimerize and both bind to MIDD1. Indeed, functional redundancy between the two genes is evident from the much stronger phenotypes seen in double mutant situations compared to either single mutants (Fig. 6). Embryos carrying homozygous loss-of-function mutations at both loci were not viable, indicating that AtKIN13 function is essential for embryo development. Similarly, downregulating AtKIN13A expression in an atkin13b mutant or vice versa resulted in strongly impaired stem or petal growth due to reduced cell expansion. Given the known roles of AtKIN13A in ensuring an even distribution of Golgi stacks in the cells [27], [29] and in depolymerizing microtubules to determine the pattern of cell-wall deposition [31], [32], as well as our evidence for a function in modulating cell-wall synthesis, we conclude that the activity of the two AtKIN13 genes is essential for normal cell-wall synthesis and thus plant-cell growth.

Why do different scenarios of reducing AtKIN13 function lead to different outcomes, i.e. increased cell expansion in one case, reduced cell expansion in the other? We propose that when AtKIN13 activity is only moderately reduced, as in the atkin13a mutants, the increased cell expansion represents a secondary effect due to triggering of the THE1-dependent signaling pathway by an initial cell wall-related defect caused by the atkin13a mutation; thus, in this case the secondary phenotype would outweigh the effect of the primary defect. Upon a stronger reduction in AtKIN13 activity when both paralogues are compromised, the primary defect in cell-wall synthesis due to the atkin13 mutation would be so severe in restricting cell growth as to outweigh the secondary effect of the THE1-dependent pathway, which is likely also triggered in these cases.

AtKIN13A interacts with AN in controlling plant-cell growth

Given their opposite effects on trichome branching, AN and AtKIN13A had been proposed to act in a common pathway to target cell-wall loosening enzymes to sites of branch initiation [30]. A role for AN in regulating Golgi function as a plant orthologue to animal BARS has recently been demonstrated [35]. If the extra trichome branching seen in atkin13a mutants were indeed due to ectopic secretion from the clustered Golgi stacks, interfering with this secretion by blocking AN function would be expected to abrogate the increased branch formation. We find genetic evidence supporting this notion (Fig. 3). The an mutation is epistatic to the atkin13a mutation regarding trichome branching, suggesting that the clustering of Golgi stacks that results from loss of AtKIN13A function does not lead to the formation of extra branches in the absence of AN activity.

Regarding phenotypes other than trichome branching, the interpretation of the genetic interaction between AN and AtKIN13A is less straightforward (Fig. 3). Double mutant plants show a synergistic phenotype with respect to rosette growth and the organization of the inflorescence, while their cellular phenotype in petals is rather additive. Thus, different developmental or growth processes may depend differently on an even distribution of Golgi stacks in the cells versus efficient secretion from these Golgi stacks; alternatively, AtKIN13A may transport different cargo molecules or vesicles in different cells.

AtKIN13A and the control of post-mitotic cell expansion

Reduced AtKIN13 function in atkin13a mutants causes excess expansion of petal cells to a larger volume (Fig. 2). This increased cell expansion is accompanied by the deposition of more cell-wall material and dry matter, yet it does not coincide with ectopic endoreduplication. It is unclear at present, however, whether the increased cell-wall synthesis drives the excess cell expansion, or whether stronger cell expansion causes the increased cell-wall synthesis as a consequence. How can reduced activity of a factor that appears to be required for normal Golgi distribution and cell growth lead to enhanced cell expansion? The strongest evidence in this regard comes from our double mutant analysis with the1 (Fig. 4,5). Loss of THE1 activity abolishes not only the excess cell expansion of atkin13a mutant petal cells, but also the structural alterations of the cell wall as detected by FTIR analysis and the suppressed expression of primary cell wall-associated CesA subunit genes. Thus, reduced AtKIN13A activity appears to trigger signalling via the THE1 pathway, but not the WAK2 pathway, resulting in larger cells and an altered cell-wall structure. This reflects the two functions that have been previously ascribed to THE1 in cell-wall integrity signalling and in promoting cell expansion [41], [42]. Surprisingly, however, the THE1-dependent altered cell-wall structure and reduced CesA gene expression in atkin13a mutants do not seem to be accompanied by obvious biochemical changes in cell-wall composition or in cellulose-microfibril arrangement, as our monosaccharide profiling and Scarlet 4B staining did not detect any significant differences.

At present it is unclear what triggers activation of the THE1 signalling pathway in atkin13a mutants; yet, given the known role of AtKIN13A in dispersing the Golgi stacks within the cells [27], it is conceivable that an uneven Golgi distribution results in spatially uneven cell-wall deposition that sets off THE1 signalling, potentially due to altered mechanical properties. The proposition that altered AtKIN13A activity modifies the pattern of cell-wall deposition has been demonstrated in the case of xylem cells [31], [32]. However, if also true for petal cells, this effect would appear to be rather subtle, as our cross-sections through the petal cells did not uncover gross unevenness in cell-wall thickness.

In conclusion, we have identified an essential role for AtKIN13 activity in plant-cell growth. Altering this activity changes the amount of the cell wall that is deposited and causes enhanced or decreased cell expansion. In particular, a moderate reduction in AtKIN13 activity leads to increased cell expansion via activation of the THE1-dependent cell-wall integrity pathway. Stronger impairment of AtKIN13 function, however, causes reduced cell expansion, most likely due to impaired microtubule depolymerization and Golgi function. Thus, our results support an important role of the cell wall in limiting cell expansion and thus final cell and organ size in plants, and they provide a compelling case for the functional interplay between cell-wall integrity sensing and cell expansion.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Arabidopsis Thaliana (L.) Heynh was used for this study. atkin13a-2 (SAIL_761_B04), atkin13a-4 (SALK_023418) and atkin13b-1 (SAIL_60_C07), the1-4 (SAIL_683_H03) and wak2-1 (SAIL_286_E03) mutants were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC; http://arabidopsis.info/). The an-2 mutant has been described [34]. atkin13a-3 was originally in the Landberg erecta background from the EMS screen, and was introgressed into the Col-0 background by back-crossing four times. Col-0 and Ler were used as wild-type lines. T-DNA insertions and genotypes were confirmed by PCR amplification by using specific primers as described in the SIGnAL database (http://signal.salk.edu, Supplemental Table S1). The plants were grown under 16 h day∶8 h night conditions with fluorescent illumination (approximately 48 µmol m−2 sec−1) at 22°C.

Genetic mapping

To map the atkin13a-3 mutation, atkin13a-3 in Landsberg erecta was crossed to Col-0 and the resulting F2 population was used for mapping using molecular markers available from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR; www.arabidopsis.org), mostly ones based on the Cereon polymorphism database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/browse/Cereon/index.jsp; [59]). For the fine-mapping, 526 F2 individuals were used; note that not all of these were genotyped for the more distant markers, explaining the different numbers of recombinants found in intervals I, II and III in Fig. S1. For critical recombinants, progeny testing was performed to verify the genotype at the mutant locus by analyzing the segregation of the phenotype in the progeny. A summary of the mapping is shown in Fig. S1, and the primers used are given in Supplemental Table S1.

Phenotypic analysis

Organ and cell sizes were measured as described [44], [60]. Values are represented as mean + SD. Each value corresponds to at least ten petals from at least five plants. Hypocotyl elongation was measured after growing seedlings for 8 days in the dark on MS plates.

Molecular cloning and genetic transformation

Constructs for plant transformation were generated, and plant transformation was performed by using standard techniques [61]. Oligonucleotides used are indicated in Supplemental Table S1. For mutant complementation, the AtKIN13A genomic sequence was amplified using primers pAtKIN13A_FOR_SacI and AtKIN13A_REV_PstI, subcloned into ML939 and transferred from there into a pBar-derivative [62]. Generation of artificial microRNA constructs was performed as described (http://wmd3.weigelworld.org/downloads/Cloning_of_artificial_microRNAs.pdf), and assembled amiRNAs were ligated to the AlcA promoter and inserted into a plant transformation vector derived from pBar containing Pro35S:AlcR—ProAlcA:CFP cassettes. The resulting construct thus allows simultaneous induction of amiRNA and CFP expression throughout the plant by EtOH treatment.

Transmission and freeze-fracture scanning electron microscopy

Petals were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and embedded in LR White resin (London Resin Company, Reading, Berkshire, UK) as described [63]. The material was sectioned with a diamond knife using a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica, Milton Keynes). Semi-thin sections of approx. 500 nm were stained with Toluidine blue for light microscopy, whereas ultrathin sections of approx. 90 nm were collected for electron microscopy. These were picked up on copper grids which had been pyroxylin and carbon-coated. The sections were stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate and 2% lead citrate and viewed in a FEI Tecnai 20 transmission electron microscope (FEI UK Ltd, Cambridge, UK) at 200 kV. TIF digital image files were recorded using an AMT XR60 digital camera (Deben, Bury St Edmunds, UK).

Petals were cryo-fixed and freeze-fractured as described [64], using an ALTO 2500 cryo-system (Gatan, Oxford, England) attached to a Zeiss Supra 55 VP FEG scanning electron microscope (Zeiss SMT, Germany). The sample was imaged at 3 kV and digital TIF files were stored.

Dry-weight analysis

To prepare cell wall materials, petals were freeze-dried and milled by rapid shaking with a ball bearing for 20 min and washed by 70% of ethanol, then rinsed by methanol-chloroform (1∶1, v/v). Cell wall materials were dried by using vacuum dryer for 2d and measured.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

More than ten 20-day old leaves were pre-cleaned by treating with 70% ethanol, followed by methanol:chloroform (1∶1, v:v) and finally acetone, air-dried, and homogenized by ball milling. The dry cell-wall material was loaded between two CaF2 windows. The spectra were obtained with a Perkin Elmer GX 2000 FTIR spectrometer [65]. For each sample 128 scans were co-added to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. Spectra were background corrected by subtraction of the blank. Using the Spectrum 5.0.1 software the spectra were baseline-corrected and normalized. Spectra were analyzed by the covariance-matrix approach for Principal Component analysis [66]. Exploratory Principal Component Analysis has been used before to characterize differences in FTIR spectra [67]; this approach derives variables, so-called Principal Components (PCs), that quantify the variance in data sets of high dimensionality, such as FTIR spectra.

Cell wall biochemical analyses

The cell wall biochemical assay was done as described [68]. Briefly, cell wall monosaccharides were assayed after hydrolysis with 2M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) as alditol acetate by gas chromatography performed on an Agilent 6890N GC System coupled with an Agilent 5973N Mass Selective Detector (Waldbronn, Germany). Myo-Inositol was added as an internal standard. Cellulose was determined on the fraction resistant to extraction with 2M TFA using glucose equivalents as standard by anthrone assay [69]. Uronic acids were colorimetrically quantified using the soluble 2M TFA fraction using 2-hydroxydiphenyl as reagent and galacturonic-acid as standard [70]. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

For qRT-PCR analysis, total RNA was extracted using a TRIzol (Invitrogen) from inflorescences of more than five plants per sample. Extracted RNA was treated with TURBO DNA-free kit (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed on a LightCycler LC480 (Roche).

Accession numbers

AGI codes of genes discussed in this paper are: AtKIN13A (At3g16630), AtKIN13B (At3g16060), THE1 (At5g54380), WAK2 (At1g21270), AN (At1g01510), CesA1 (At4g32410), CesA3 (At5g05170), CesA6 (At5g64740).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. PowellAE, LenhardM (2012) Control of organ size in plants. Curr Biol 22: R360–367.

2. Sugimoto-ShirasuK, RobertsK (2003) “Big it up”: Endoreduplication and cell-size control in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6 : 544–553.

3. MelaragnoJE, MehrotraB, ColemanAW (1993) Relationship between endopolyploidy and cell size in epidermal tissue of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5 : 1661–1668.

4. Taiz L, Zeiger E (2010) Plant physiology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

5. WoltersH, JurgensG (2009) Survival of the flexible: Hormonal growth control and adaptation in plant development. Nat Rev Genet 10 : 305–317.

6. BaiMY, FanM, OhE, WangZY (2012) A triple helix-loop-helix/basic helix-loop-helix cascade controls cell elongation downstream of multiple hormonal and environmental signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 : 4917–4929.

7. IkedaM, FujiwaraS, MitsudaN, Ohme-TakagiM (2012) A triantagonistic basic helix-loop-helix system regulates cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 : 4483–4497.

8. HuY, PohHM, ChuaNH (2006) The Arabidopsis ARGOS-LIKE gene regulates cell expansion during organ growth. Plant J 47 : 1–9.

9. DeprostD, YaoL, SormaniR, MoreauM, LeterreuxG, et al. (2007) The Arabidopsis TOR kinase links plant growth, yield, stress resistance and mrna translation. EMBO Rep 8 : 864–870.

10. MenandB, DesnosT, NussaumeL, BergerF, BouchezD, et al. (2002) Expression and disruption of the Arabidopsis TOR (target of rapamycin) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 : 6422–6427.

11. Menand B, Robaglia C (2004) Plant cell growth. In: Hall MN, editor. Cell growth: Control of cell size. 01 ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. pp. 625–637.

12. BrioudesF, JolyC, SzecsiJ, VaraudE, LerouxJ, et al. (2009) Jasmonate controls late development stages of petal growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 60 : 1070–1080.

13. SzecsiJ, JolyC, BordjiK, VaraudE, CockJM, et al. (2006) BIGPETALp, a bHLH transcription factor is involved in the control of Arabidopsis petal size. Embo J 25 : 3912–3920.

14. VaraudE, BrioudesF, SzecsiJ, LerouxJ, BrownS, et al. (2011) AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 regulates Arabidopsis petal growth by interacting with the bHLH transcription factor BIGPETALp. Plant Cell 23 : 973–983.

15. CosgroveDJ (2005) Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6 : 850–861.

16. ChoHT, CosgroveDJ (2000) Altered expression of expansin modulates leaf growth and pedicel abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 : 9783–9788.

17. ChoiD, LeeY, ChoHT, KendeH (2003) Regulation of expansin gene expression affects growth and development in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell 15 : 1386–1398.

18. ZenoniS, RealeL, TornielliGB, LanfaloniL, PorcedduA, et al. (2004) Downregulation of the Petunia hybrida alpha-expansin gene PhEXP1 reduces the amount of crystalline cellulose in cell walls and leads to phenotypic changes in petal limbs. Plant Cell 16 : 295–308.

19. SomervilleC (2006) Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22 : 53–78.

20. PerssonS, ParedezA, CarrollA, PalsdottirH, DoblinM, et al. (2007) Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 15566–15571.

21. CrowellEF, BischoffV, DesprezT, RollandA, StierhofYD, et al. (2009) Pausing of Golgi bodies on microtubules regulates secretion of cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 : 1141–1154.

22. GutierrezR, LindeboomJJ, ParedezAR, EmonsAM, EhrhardtDW (2009) Arabidopsis cortical microtubules position cellulose synthase delivery to the plasma membrane and interact with cellulose synthase trafficking compartments. Nat Cell Biol 11 : 797–806.

23. ParedezAR, SomervilleCR, EhrhardtDW (2006) Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science 312 : 1491–1495.

24. WightmanR, TurnerS (2010) Trafficking of the plant cellulose synthase complex. Plant Physiol 153 : 427–432.

25. SampathkumarA, GutierrezR, McFarlaneHE, BringmannM, LindeboomJ, et al. (2013) Patterning and lifetime of plasma membrane-localized cellulose synthase is dependent on actin organization in Arabidopsis interphase cells. Plant Physiol 162 : 675–688.

26. BringmannM, LiE, SampathkumarA, KocabekT, HauserMT, et al. (2012) POM-POM2/cellulose synthase interacting1 is essential for the functional association of cellulose synthase and microtubules in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 : 163–177.

27. LuL, LeeYR, PanR, MaloofJN, LiuB (2005) An internal motor kinesin is associated with the Golgi apparatus and plays a role in trichome morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Cell 16 : 811–823.

28. ZhongR, BurkDH, MorrisonWH3rd, YeZH (2002) A kinesin-like protein is essential for oriented deposition of cellulose microfibrils and cell wall strength. Plant Cell 14 : 3101–3117.

29. WeiL, ZhangW, LiuZ, LiY (2009) AtKinesin-13a is located on Golgi-associated vesicle and involved in vesicle formation/budding in Arabidopsis root-cap peripheral cells. BMC Plant Biol 9 : 138.

30. SmithLG, OppenheimerDG (2005) Spatial control of cell expansion by the plant cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21 : 271–295.

31. OdaY, FukudaH (2013) Rho of plant GTPase signaling regulates the behavior of Arabidopsis kinesin-13a to establish secondary cell wall patterns. Plant Cell 25 : 4439–4450.

32. OdaY, FukudaH (2013) The dynamic interplay of plasma membrane domains and cortical microtubules in secondary cell wall patterning. Front Plant Sci 4 : 511.

33. FolkersU, KirikV, SchobingerU, FalkS, KrishnakumarS, et al. (2002) The cell morphogenesis gene ANGUSTIFOLIA encodes a CtBP/BARS-like protein and is involved in the control of the microtubule cytoskeleton. Embo J 21 : 1280–1288.

34. KimGT, ShodaK, TsugeT, ChoKH, UchimiyaH, et al. (2002) The ANGUSTIFOLIA gene of Arabidopsis, a plant CtBP gene, regulates leaf-cell expansion, the arrangement of cortical microtubules in leaf cells and expression of a gene involved in cell-wall formation. Embo J 21 : 1267–1279.

35. MinamisawaN, SatoM, ChoKH, UenoH, TakechiK, et al. (2011) ANGUSTIFOLIA, a plant homolog of CtBP/BARS, functions outside the nucleus. Plant J 68 : 788–799.

36. HamannT, DennessL (2011) Cell wall integrity maintenance in plants: Lessons to be learned from yeast? Plant Signal Behav 6 : 1706–1709.

37. KohornBD, JohansenS, ShishidoA, TodorovaT, MartinezR, et al. (2009) Pectin activation of MAP kinase and gene expression is WAK2 dependent. Plant J 60 : 974–982.

38. KohornBD, KobayashiM, JohansenS, RieseJ, HuangLF, et al. (2006) An Arabidopsis cell wall-associated kinase required for invertase activity and cell growth. Plant J 46 : 307–316.

39. WagnerTA, KohornBD (2001) Wall-associated kinases are expressed throughout plant development and are required for cell expansion. Plant Cell 13 : 303–318.

40. Boisson-DernierA, KesslerSA, GrossniklausU (2011) The walls have ears: The role of plant CrRLK1Ls in sensing and transducing extracellular signals. J Exp Bot 62 : 1581–1591.

41. HematyK, SadoPE, Van TuinenA, RochangeS, DesnosT, et al. (2007) A receptor-like kinase mediates the response of Arabidopsis cells to the inhibition of cellulose synthesis. Curr Biol 17 : 922–931.

42. GuoH, LiL, YeH, YuX, AlgreenA, et al. (2009) Three related receptor-like kinases are required for optimal cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 7648–7653.

43. AlonsoJM, StepanovaAN, LeisseTJ, KimCJ, ChenH, et al. (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 : 653–657.

44. HoriguchiG, FujikuraU, FerjaniA, IshikawaN, TsukayaH (2006) Large-scale histological analysis of leaf mutants using two simple leaf observation methods: Identification of novel genetic pathways governing the size and shape of leaves. Plant J 48 : 638–644.

45. RobbinsCT, MoenAN (1975) Composition and digestibility of several deciduous browses in the northeast. The Journal of Wildlife Management 39 : 337–341.

46. GendreauE, TraasJ, DesnosT, GrandjeanO, CabocheM, et al. (1997) Cellular basis of hypocotyl growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 114 : 295–305.

47. ClouseSD, LangfordM, McMorrisTC (1996) A brassinosteroid-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits multiple defects in growth and development. Plant Physiol 111 : 671–678.

48. GuzmanP, EckerJR (1990) Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2 : 513–523.

49. TsugeT, TsukayaH, UchimiyaH (1996) Two independent and polarized processes of cell elongation regulate leaf blade expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana (l.) heynh. Development 122 : 1589–1600.

50. KimGT, FujiokaS, KozukaT, TaxFE, TakatsutoS, et al. (2005) CYP90C1 and CYP90D1 are involved in different steps in the brassinosteroid biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 41 : 710–721.

51. AndersonCT, CarrollA, AkhmetovaL, SomervilleC (2010) Real-time imaging of cellulose reorientation during cell wall expansion in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol 152 : 787–796.

52. LandreinB, LatheR, BringmannM, VouillotC, IvakovA, et al. (2013) Impaired cellulose synthase guidance leads to stem torsion and twists phyllotactic patterns in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 23 : 895–900.

53. WinterD, VinegarB, NahalH, AmmarR, WilsonGV, et al. (2007) An “electronic fluorescent pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One 2: e718.

54. SchwabR, OssowskiS, WarthmannN, WeigelD (2010) Directed gene silencing with artificial microRNAs. Methods Mol Biol 592 : 71–88.

55. RoslanHA, SalterMG, WoodCD, WhiteMR, CroftKP, et al. (2001) Characterization of the ethanol-inducible alc gene-expression system in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 28 : 225–235.

56. MuchaE, HoefleC, HuckelhovenR, BerkenA (2010) RIP3 and AtKinesin-13A - a novel interaction linking rho proteins of plants to microtubules. Eur J Cell Biol 89 : 906–916.

57. ManeyT, WagenbachM, WordemanL (2001) Molecular dissection of the microtubule depolymerizing activity of mitotic centromere-associated kinesin. The Journal of biological chemistry 276 : 34753–34758.

58. MooresCA, MilliganRA (2006) Lucky 13 - microtubule depolymerisation by kinesin-13 motors. J Cell Sci 119 : 3905–3913.

59. JanderG, NorrisSR, RounsleySD, BushDF, LevinIM, et al. (2002) Arabidopsis map-based cloning in the post-genome era. Plant Physiol 129 : 440–450.

60. DischS, AnastasiouE, SharmaVK, LauxT, FletcherJC, et al. (2006) The E3 ubiquitin ligase BIG BROTHER controls Arabidopsis organ size in a dosage-dependent manner. Curr Biol 16 : 272–279.

61. CloughSJ, BentAF (1998) Floral dip: A simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16 : 735–743.

62. BeckerD, KemperE, SchellJ, MastersonR (1992) New plant binary vectors with selectable markers located proximal to the left T-DNA border. Plant Mol Biol 20 : 1195–1197.

63. LodwigEM, LeonardM, MarroquiS, WheelerTR, FindlayK, et al. (2005) Role of polyhydroxybutyrate and glycogen as carbon storage compounds in pea and bean bacteroids. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18 : 67–74.

64. DerbyshireP, FindlayK, McCannMC, RobertsK (2007) Cell elongation in Arabidopsis hypocotyls involves dynamic changes in cell wall thickness. J Exp Bot 58 : 2079–2089.

65. HinchaDK, ZutherE, HellwegeEM, HeyerAG (2002) Specific effects of fructo - and gluco-oligosaccharides in the preservation of liposomes during drying. Glycobiology 12 : 103–110.

66. KemsleyEK (1996) Discriminant analysis of high-dimensional data: A comparison of principal components analysis and partial least squares data reduction methods. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 33 : 47–61.

67. McCannMC, DefernezM, UrbanowiczBR, TewariJC, LangewischT, et al. (2007) Neural network analyses of infrared spectra for classifying cell wall architectures. Plant Physiol 143 : 1314–1326.

68. Sanchez-RodriguezC, BauerS, HematyK, SaxeF, IbanezAB, et al. (2012) Chitinase-like1/pom-pom1 and its homolog CTL2 are glucan-interacting proteins important for cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 : 589–607.

69. Dische Z (1962) General color reactions. RL Whistler and ML Wolfrom, Editors, Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry, Academic Press, New York: 478–481.

70. FilisetticozziTMCC, CarpitaNC (1991) Measurement of uronic-acids without interference from neutral sugars. Analytical Biochemistry 197 : 157–162.

71. SmythDR, BowmanJL, MeyerowitzEM (1990) Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2 : 755–767.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukční medicína

Článek An Evolutionarily Conserved Role for the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in the Regulation of MovementČlánek Requirement for Drosophila SNMP1 for Rapid Activation and Termination of Pheromone-Induced ActivityČlánek Co-regulated Transcripts Associated to Cooperating eSNPs Define Bi-fan Motifs in Human Gene NetworksČlánek Identification of a Regulatory Variant That Binds FOXA1 and FOXA2 at the Type 2 Diabetes GWAS LocusČlánek tRNA Modifying Enzymes, NSUN2 and METTL1, Determine Sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil in HeLa CellsČlánek Derlin-1 Regulates Mutant VCP-Linked Pathogenesis and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced ApoptosisČlánek A Genetic Assay for Transcription Errors Reveals Multilayer Control of RNA Polymerase II FidelityČlánek The Proprotein Convertase KPC-1/Furin Controls Branching and Self-avoidance of Sensory Dendrites inČlánek Regulation of p53 and Rb Links the Alternative NF-κB Pathway to EZH2 Expression and Cell SenescenceČlánek BMPs Regulate Gene Expression in the Dorsal Neuroectoderm of and Vertebrates by Distinct MechanismsČlánek Unkempt Is Negatively Regulated by mTOR and Uncouples Neuronal Differentiation from Growth Control

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Nejčtenější tento týden

2014 Číslo 9- Růst a vývoj dětí narozených pomocí IVF

- Intrauterinní inseminace a její úspěšnost

- Mateřský haplotyp KIR ovlivňuje porodnost živých dětí po transferu dvou embryí v rámci fertilizace in vitro u pacientek s opakujícími se samovolnými potraty nebo poruchami implantace

- Akutní intermitentní porfyrie

- Primární hyperoxalurie – aktuální možnosti diagnostiky a léčby

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Translational Regulation of the Post-Translational Circadian Mechanism

- An Evolutionarily Conserved Role for the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in the Regulation of Movement

- Eliminating Both Canonical and Short-Patch Mismatch Repair in Suggests a New Meiotic Recombination Model

- Requirement for Drosophila SNMP1 for Rapid Activation and Termination of Pheromone-Induced Activity

- Co-regulated Transcripts Associated to Cooperating eSNPs Define Bi-fan Motifs in Human Gene Networks

- Targeted H3R26 Deimination Specifically Facilitates Estrogen Receptor Binding by Modifying Nucleosome Structure

- Role for Circadian Clock Genes in Seasonal Timing: Testing the Bünning Hypothesis

- The Tandem Repeats Enabling Reversible Switching between the Two Phases of β-Lactamase Substrate Spectrum

- The Association of the Vanin-1 N131S Variant with Blood Pressure Is Mediated by Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation and Loss of Function

- Identification of a Regulatory Variant That Binds FOXA1 and FOXA2 at the Type 2 Diabetes GWAS Locus

- Regulation of Flowering by the Histone Mark Readers MRG1/2 via Interaction with CONSTANS to Modulate Expression

- The Actomyosin Machinery Is Required for Retinal Lumen Formation

- Plays a Conserved Role in Assembly of the Ciliary Motile Apparatus

- Hidden Diversity in Honey Bee Gut Symbionts Detected by Single-Cell Genomics

- Ribosome Rescue and Translation Termination at Non-Standard Stop Codons by ICT1 in Mammalian Mitochondria

- tRNA Modifying Enzymes, NSUN2 and METTL1, Determine Sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil in HeLa Cells

- Causal Variation in Yeast Sporulation Tends to Reside in a Pathway Bottleneck

- Tissue-Specific RNA Expression Marks Distant-Acting Developmental Enhancers

- WC-1 Recruits SWI/SNF to Remodel and Initiate a Circadian Cycle

- Clonal Expansion of Early to Mid-Life Mitochondrial DNA Point Mutations Drives Mitochondrial Dysfunction during Human Ageing

- Methylation QTLs Are Associated with Coordinated Changes in Transcription Factor Binding, Histone Modifications, and Gene Expression Levels

- Differential Management of the Replication Terminus Regions of the Two Chromosomes during Cell Division

- Obesity-Linked Homologues and Establish Meal Frequency in

- Derlin-1 Regulates Mutant VCP-Linked Pathogenesis and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Apoptosis

- Stress-Induced Nuclear RNA Degradation Pathways Regulate Yeast Bromodomain Factor 2 to Promote Cell Survival

- The MAPK p38c Regulates Oxidative Stress and Lipid Homeostasis in the Intestine

- Widespread Genome Reorganization of an Obligate Virus Mutualist

- Trans-kingdom Cross-Talk: Small RNAs on the Move

- The Vip1 Inositol Polyphosphate Kinase Family Regulates Polarized Growth and Modulates the Microtubule Cytoskeleton in Fungi

- Myosin Vb Mediated Plasma Membrane Homeostasis Regulates Peridermal Cell Size and Maintains Tissue Homeostasis in the Zebrafish Epidermis

- GLD-4-Mediated Translational Activation Regulates the Size of the Proliferative Germ Cell Pool in the Adult Germ Line

- Genome Wide Association Studies Using a New Nonparametric Model Reveal the Genetic Architecture of 17 Agronomic Traits in an Enlarged Maize Association Panel

- Translational Regulation of the DOUBLETIME/CKIδ/ε Kinase by LARK Contributes to Circadian Period Modulation

- Positive Selection and Multiple Losses of the LINE-1-Derived Gene in Mammals Suggest a Dual Role in Genome Defense and Pluripotency

- Out of Balance: R-loops in Human Disease

- A Genetic Assay for Transcription Errors Reveals Multilayer Control of RNA Polymerase II Fidelity

- Altered Behavioral Performance and Live Imaging of Circuit-Specific Neural Deficiencies in a Zebrafish Model for Psychomotor Retardation

- Nipbl and Mediator Cooperatively Regulate Gene Expression to Control Limb Development

- Meta-analysis of Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Gradient of Severity in Cognitive Impairments

- The Proprotein Convertase KPC-1/Furin Controls Branching and Self-avoidance of Sensory Dendrites in

- Hydroxymethylated Cytosines Are Associated with Elevated C to G Transversion Rates

- Memory and Fitness Optimization of Bacteria under Fluctuating Environments

- Regulation of p53 and Rb Links the Alternative NF-κB Pathway to EZH2 Expression and Cell Senescence

- Interspecific Tests of Allelism Reveal the Evolutionary Timing and Pattern of Accumulation of Reproductive Isolation Mutations

- PRO40 Is a Scaffold Protein of the Cell Wall Integrity Pathway, Linking the MAP Kinase Module to the Upstream Activator Protein Kinase C

- Low Levels of p53 Protein and Chromatin Silencing of p53 Target Genes Repress Apoptosis in Endocycling Cells

- SPDEF Inhibits Prostate Carcinogenesis by Disrupting a Positive Feedback Loop in Regulation of the Foxm1 Oncogene

- RRP6L1 and RRP6L2 Function in Silencing Regulation of Antisense RNA Synthesis

- BMPs Regulate Gene Expression in the Dorsal Neuroectoderm of and Vertebrates by Distinct Mechanisms

- Unkempt Is Negatively Regulated by mTOR and Uncouples Neuronal Differentiation from Growth Control

- Atkinesin-13A Modulates Cell-Wall Synthesis and Cell Expansion in via the THESEUS1 Pathway

- Dopamine Signaling Leads to Loss of Polycomb Repression and Aberrant Gene Activation in Experimental Parkinsonism

- Histone Methyltransferase MMSET/NSD2 Alters EZH2 Binding and Reprograms the Myeloma Epigenome through Global and Focal Changes in H3K36 and H3K27 Methylation

- Bipartite Recognition of DNA by TCF/Pangolin Is Remarkably Flexible and Contributes to Transcriptional Responsiveness and Tissue Specificity of Wingless Signaling

- The Olfactory Transcriptomes of Mice

- Muscular Dystrophy-Associated and Variants Disrupt Nuclear-Cytoskeletal Connections and Myonuclear Organization

- Interplay of dFOXO and Two ETS-Family Transcription Factors Determines Lifespan in

- Evidence for Widespread Positive and Negative Selection in Coding and Conserved Noncoding Regions of

- Genome-Wide Association Meta-analysis of Neuropathologic Features of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias

- Rejuvenation of Meiotic Cohesion in Oocytes during Prophase I Is Required for Chiasma Maintenance and Accurate Chromosome Segregation

- Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals

- Local Effect of Enhancer of Zeste-Like Reveals Cooperation of Epigenetic and -Acting Determinants for Zygotic Genome Rearrangements

- Differential Responses to Wnt and PCP Disruption Predict Expression and Developmental Function of Conserved and Novel Genes in a Cnidarian

- PLOS Genetics

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals

- Nipbl and Mediator Cooperatively Regulate Gene Expression to Control Limb Development

- Genome Wide Association Studies Using a New Nonparametric Model Reveal the Genetic Architecture of 17 Agronomic Traits in an Enlarged Maize Association Panel

- Histone Methyltransferase MMSET/NSD2 Alters EZH2 Binding and Reprograms the Myeloma Epigenome through Global and Focal Changes in H3K36 and H3K27 Methylation

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání