-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaRisk Factors and Outcomes for Late Presentation for HIV-Positive Persons in Europe: Results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE)

Background:

Few studies have monitored late presentation (LP) of HIV infection over the European continent, including Eastern Europe. Study objectives were to explore the impact of LP on AIDS and mortality.Methods and Findings:

LP was defined in Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) as HIV diagnosis with a CD4 count <350/mm3 or an AIDS diagnosis within 6 months of HIV diagnosis among persons presenting for care between 1 January 2000 and 30 June 2011. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with LP and Poisson regression to explore the impact on AIDS/death. 84,524 individuals from 23 cohorts in 35 countries contributed data; 45,488 were LP (53.8%). LP was highest in heterosexual males (66.1%), Southern European countries (57.0%), and persons originating from Africa (65.1%). LP decreased from 57.3% in 2000 to 51.7% in 2010/2011 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.95–0.97). LP decreased over time in both Central and Northern Europe among homosexual men, and male and female heterosexuals, but increased over time for female heterosexuals and male intravenous drug users (IDUs) from Southern Europe and in male and female IDUs from Eastern Europe. 8,187 AIDS/deaths occurred during 327,003 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after HIV diagnosis, LP was associated with over a 13-fold increased incidence of AIDS/death in Southern Europe (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 13.02; 95% CI 8.19–20.70) and over a 6-fold increased rate in Eastern Europe (aIRR 6.64; 95% CI 3.55–12.43).Conclusions:

LP has decreased over time across Europe, but remains a significant issue in the region in all HIV exposure groups. LP increased in male IDUs and female heterosexuals from Southern Europe and IDUs in Eastern Europe. LP was associated with an increased rate of AIDS/deaths, particularly in the first year after HIV diagnosis, with significant variation across Europe. Earlier and more widespread testing, timely referrals after testing positive, and improved retention in care strategies are required to further reduce the incidence of LP.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 10(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001510Summary

Background:

Few studies have monitored late presentation (LP) of HIV infection over the European continent, including Eastern Europe. Study objectives were to explore the impact of LP on AIDS and mortality.Methods and Findings:

LP was defined in Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) as HIV diagnosis with a CD4 count <350/mm3 or an AIDS diagnosis within 6 months of HIV diagnosis among persons presenting for care between 1 January 2000 and 30 June 2011. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with LP and Poisson regression to explore the impact on AIDS/death. 84,524 individuals from 23 cohorts in 35 countries contributed data; 45,488 were LP (53.8%). LP was highest in heterosexual males (66.1%), Southern European countries (57.0%), and persons originating from Africa (65.1%). LP decreased from 57.3% in 2000 to 51.7% in 2010/2011 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.96; 95% CI 0.95–0.97). LP decreased over time in both Central and Northern Europe among homosexual men, and male and female heterosexuals, but increased over time for female heterosexuals and male intravenous drug users (IDUs) from Southern Europe and in male and female IDUs from Eastern Europe. 8,187 AIDS/deaths occurred during 327,003 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after HIV diagnosis, LP was associated with over a 13-fold increased incidence of AIDS/death in Southern Europe (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 13.02; 95% CI 8.19–20.70) and over a 6-fold increased rate in Eastern Europe (aIRR 6.64; 95% CI 3.55–12.43).Conclusions:

LP has decreased over time across Europe, but remains a significant issue in the region in all HIV exposure groups. LP increased in male IDUs and female heterosexuals from Southern Europe and IDUs in Eastern Europe. LP was associated with an increased rate of AIDS/deaths, particularly in the first year after HIV diagnosis, with significant variation across Europe. Earlier and more widespread testing, timely referrals after testing positive, and improved retention in care strategies are required to further reduce the incidence of LP.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

Approximately 40%–60% of HIV-positive persons in developed countries continue to be diagnosed with HIV at a late stage of infection [1]. According to the latest consensus definition from the HIV in Europe study group, late presenters are defined as persons presenting to a clinic that can prescribe antiretroviral therapy (ART) with a CD4 count of less than 350/mm3 or an AIDS defining illness [2], the current World Health Organization's recommended threshold for initiation of ART [3]. Late presentation, which may reflect late diagnosis and/or late entry into care, has consequences both for the individual, in terms of poorer outcomes [4]–[6], and for society in terms of the risk of onward transmission due to uncontrolled viremia and lack of awareness of HIV serostatus [7],[8]. Late presentation also has an economic impact, with higher resource use, particularly in the first few months following presentation [9],[10]. Barriers to testing from the patients perspective include concerns about the impact of a positive result, fears around discrimination, confidentiality, criminalisation of risk behaviours, and limited knowledge about accessing testing or treatment on testing positive [11]. Reported concerns by clinicians include language barriers, the belief that lengthy counselling is required, worry about informing individuals of a HIV-positive test result, and lack of knowledge about HIV and potential risk behaviours [12].

Many studies have presented data on late presentation, generally focusing on a specific country or region within a country and applying various definitions for late presentation. Data from Eastern Europe is particularly scarce and hence a Europe-wide perspective of late presentation using uniform definitions can help inform policy and decision making on future continent-wide HIV testing strategies. Such results will provide a platform for future monitoring of late presentation following appropriate interventions.

The Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study provides a unique opportunity to describe the epidemiology of those testing HIV positive at a late stage of HIV infection compared to those testing earlier, and to look at regional differences within HIV exposure groups. The aims of the present analyses were to describe trends in late presentation over time in different regions of Europe and according to HIV exposure group, and to investigate the clinical consequences of late presentation.

Methods

Patients

COHERE is a collaboration of 33 cohorts from across Europe and is part of the EuroCoord network (www.EuroCoord.net). COHERE was established in 2005 with the aim of conducting epidemiological research on the prognosis and outcome of HIV-positive persons, which the individual contributing cohorts cannot address themselves because of sample size or heterogeneity of specific subgroups of HIV-positive persons. Local ethical committee and/or other regulatory approval were obtained as applicable according to local and/or national regulations in all participating cohorts unless no such requirement applied to observational studies according to national regulations. Each cohort submits data using the standardized HIV Collaboration Data Exchange Protocol (HICDEP) [13], including information on patient demographics, use of cART, CD4 counts, AIDS, and deaths. Further details can be found at http://www.eurocoord.net/partners/founding_networks/cohere.aspx.

Twenty three cohorts across 35 European countries provided data for the present analysis. All persons aged ≥16 y, who presented for care (earliest of HIV diagnosis, first clinic visit, or enrolment into the participating cohort) for the first time after 1 January 2000 until 1 January 2011 were included. Baseline was defined as the date of first HIV diagnosis, or the earliest of first clinic visit or cohort enrolment if date of HIV diagnosis was missing, referred to as date of HIV diagnosis. Persons were excluded if gender or HIV diagnosis was missing, if aged <16 y, or where there was evidence of an earlier HIV diagnosis (CD4 count, AIDS diagnosis, or starting ART) more than 1 mo prior to first clinic visit, as were persons from Argentinean centres in EuroSIDA and persons from the seroconverter cohorts in COHERE, because by definition, such persons are not presenting late.

Late presentation was defined as a person diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 350/mm3 or an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Late presentation with advanced disease was defined as a person diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 200/mm3or an AIDS defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis [2]. Delayed entry into care was defined as ≥3 mo between HIV diagnosis and first clinic visit, in those where both dates were recorded. All persons were required to have at least one CD4 count measured in the 6 mo following diagnosis.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics of late presenters were compared to non-late presenters and logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with late presentation and late presentation with advanced disease. Factors investigated were age, HIV-exposure group (males having sex with males [MSM], heterosexual male, heterosexual female, male intravenous drug user [IDU], female IDU, other [including patients with unknown HIV exposure group, likely to include a number of IDUs, MSMs, and heterosexuals]), region of origin (Europe, Africa, other [including patients from Central/Southern America and Asia], unknown), European region of HIV diagnosis (based on the cohort location and defined as: South: Greece, Israel, Italy, Portugal, and Spain; Central: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxemburg, and Switzerland; North: Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and UK; East: Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine), calendar year of diagnosis, and delayed entry into care. A priori, we were interested in comparing changes over time within European regions and HIV exposure groups, and performed formal tests of interaction before presenting the stratified analyses. Logistic regression was also used to identify characteristics associated with delayed entry into care among late presenters.

Kaplan Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the probability of the composite endpoint of a new AIDS defining event/deaths and Poisson regression models to evaluate the incidence of AIDS/death. Models were adjusted for the same factors as above, and additionally the effect of time after HIV diagnosis (<1, 1–2, >2 y). Recurrent AIDS events were not collected by all participating cohorts and thus were not included.

Different sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of our findings. Analyses were repeated excluding persons where date of HIV infection was not available in the dataset and excluding persons with known delayed entry into care. We also assessed how the proportion of late presenters changed by using a different time window around the CD4 count at HIV diagnosis (1 mo, 12 mo) and also assuming those without a CD4 count measured were late presenters or not.

All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software Version 9.3 (Statistical Analysis Software).

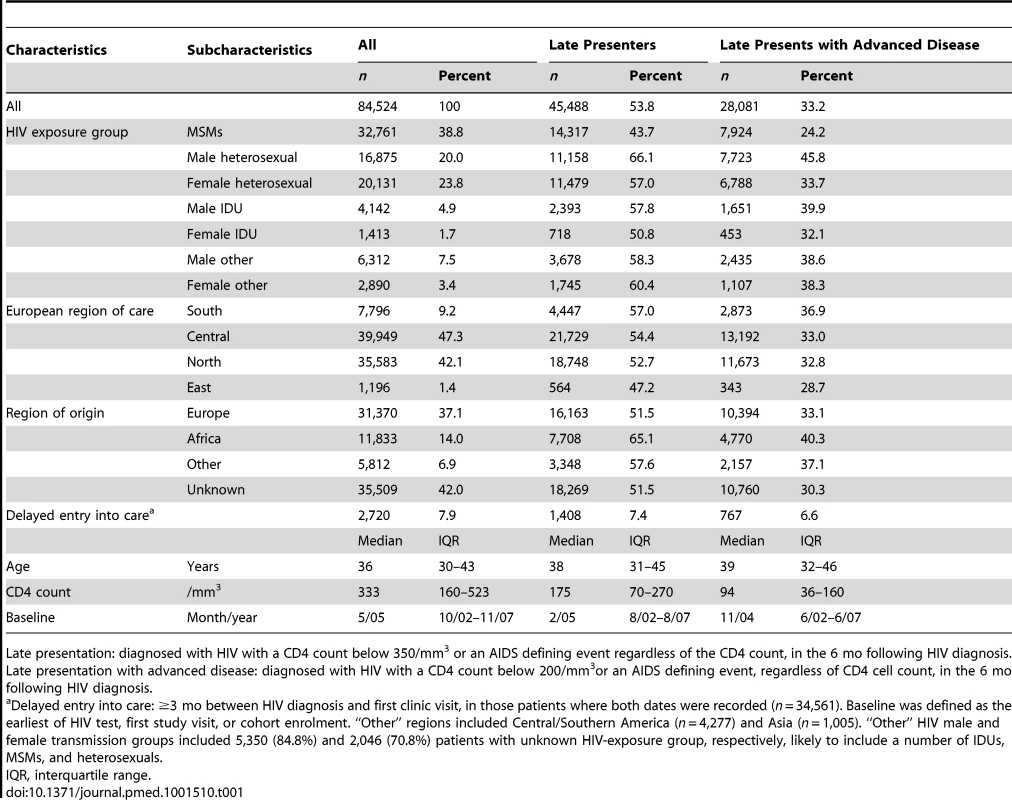

Results

Of 107,735 persons in COHERE diagnosed with HIV after 1 January 2000, 84,524 were included in these analyses (78.5%; Table S1). Persons were primarily excluded because they lacked information on CD4 count at HIV diagnosis. Excluded persons were more likely to be from “other” HIV exposure groups (i.e., not categorised as MSM, IDU, or heterosexual), from Eastern Europe, younger, to have no prior AIDS diagnosis at diagnosis, diagnosed in earlier calendar years, and less likely to die. Characteristics of the 84,524 included persons are shown in Table 1; 45,488 persons were classified as late presenters (53.8%) and 28,081 (33.2%) as late presenters with advanced disease. The highest proportion of late presenters was among heterosexual males (66.1%; 11,158/16,875), persons from clinics in Southern Europe (57.0%; 4,447/7,796), and persons originating from Africa (65.1%; 7,708/11,833). 11,903 of the late presenters had AIDS at HIV-1 diagnosis (20.6%), the most common diagnoses were Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (20.6%; 2,457/11,903), cytomegalovirus (excluding retinitis, 13.9%; 1,657/11,903), and oesophageal candidiasis (12.3%; 1,463/11,903). Among the 34,561 persons with data on both date of HIV diagnosis and first contact with a clinic, 7.9% (2,720/34,561) had delayed entry into care. Among late presenters, 7.4% had delayed entry into care (1,408/18,933); such individuals were younger (adjusted odds ratio (aOR 0.87/10 y older; 95% CI 0.83–0.91), presented later (aOR 0.96/year later; 95% CI 0.94–0.97), and were more likely to be under care in Southern Europe compared to Northern Europe (aOR 2.02; 95% CI 1.77–2.30). HIV exposure group or region of origin were not associated with delayed entry into care among late presenters.

Tab. 1. Characteristics at HIV diagnosis of late presenters and late presenters with advanced disease: COHERE 2000–2011.

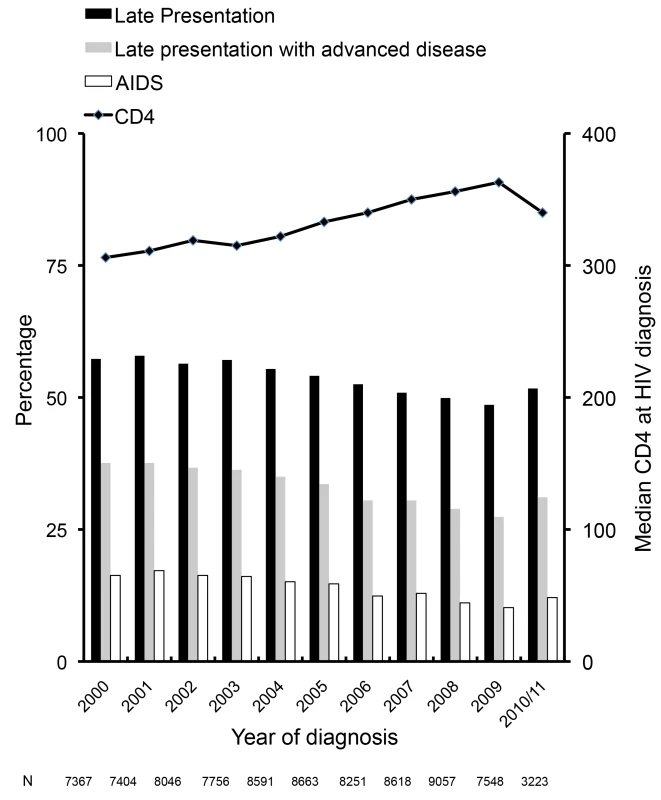

Late presentation: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 350/mm3 or an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Late presentation with advanced disease: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 200/mm3or an AIDS defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Late presentation declined from 57.3% (4,222/7,367) in 2000 to 51.7% (1,665/3,223) in 2010/2011 (Figure 1). The median CD4 count at diagnosis among all persons increased from 306/mm3 in 2000 to 363/mm3 in 2009. Factors associated with late presentation included older age (aOR 1.41/10 y older; 95% CI 1.39–1.43), and region of origin, with persons from Africa (aOR 1.75; 95% CI 1.66–1.84) and persons from other regions (aOR 1.40; 95% CI 1.32–1.48) having higher odds of late presentation compared to persons originating from Europe. Compared to persons from Central Europe, persons under care in Southern Europe (aOR 1.41; 95% CI 1.33–1.48) had higher odds of late presentation, as did all HIV-exposure groups compared to MSM. This ranged from over a doubling in heterosexual men (aOR 2.05; 95% CI 1.97–2.14) to 31% for female IDUs (aOR 1.31; 95% CI 1.18–1.46). Delayed entry into care was associated with decreased odds of late presentation (aOR 0.91; 95% CI 0.84–0.99). After adjustment for these confounders, there was a 4% decrease in the odds of late presentation per later calendar year (aOR 0.96; 95% CI 0.96–0.97). Results were similar for late presentation with advanced disease (Figure 1), with a decrease in advanced disease at presentation of 5% per year after adjustment (aOR 0.95; 95% CI 0.94–0.95). Results were highly consistent excluding patients with unknown or delayed entry into care (Table S2).

Fig. 1. Changes over time in late presentation and CD4 count at HIV diagnosis: COHERE 2000–2011.

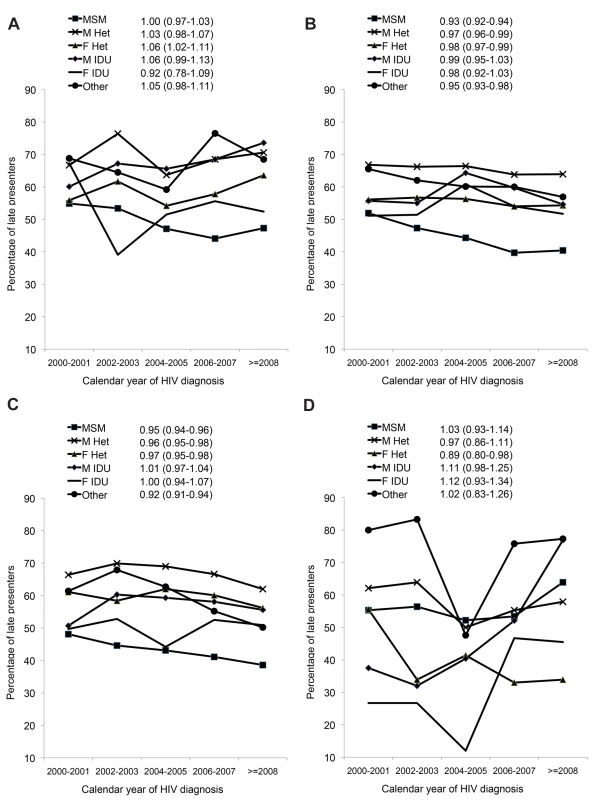

Late presentation: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 350/mm3 or an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Late presentation with advanced disease: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 200/mm3or an AIDS defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Figure 2 shows the crude percentage of late presenters within HIV-exposure groups, region, and calendar period, and the aOR of late presentation per year of later HIV diagnosis (also shown in Table S3). Later calendar year was associated with a decrease in late presentation among MSM, and male and female heterosexuals in both Central and Northern Europe (Figure 2B and 2C). For example, the proportion of MSMs with late presentation in Central Europe declined from 51.9% (1,201/2,312) in 2000/2001 to 40.4% (1,352/3,348)≥2008 (aOR 0.93 per year later; 95% CI 0.92–0.94) and from 48.1% (919/1,911) to 38.6% (1,731/4,484) in Northern Europe (Figure 2C; aOR 0.95 per year later; 95% CI 0.94–0.96). Late presentation also decreased over time in heterosexual females from Eastern Europe from 55.6% (25/45) in 2000/2001 to 33.9% (20/59)≥2008 (aOR 0.89 per year later; 95% CI 0.80–0.98). Late presentation increased in male IDUs from Southern Europe (Figure 2A; aOR 1.06 per year later; 95% CI 0.99–1.13), and also among male and female IDUs from Eastern Europe, although the aORs failed to reach statistical significance, possibly owing to the smaller number of patients from Eastern Europe.

Fig. 2. (A–D) Changes in late presentation over calendar time; stratified by HIV exposure group: COHERE 2000–2011.

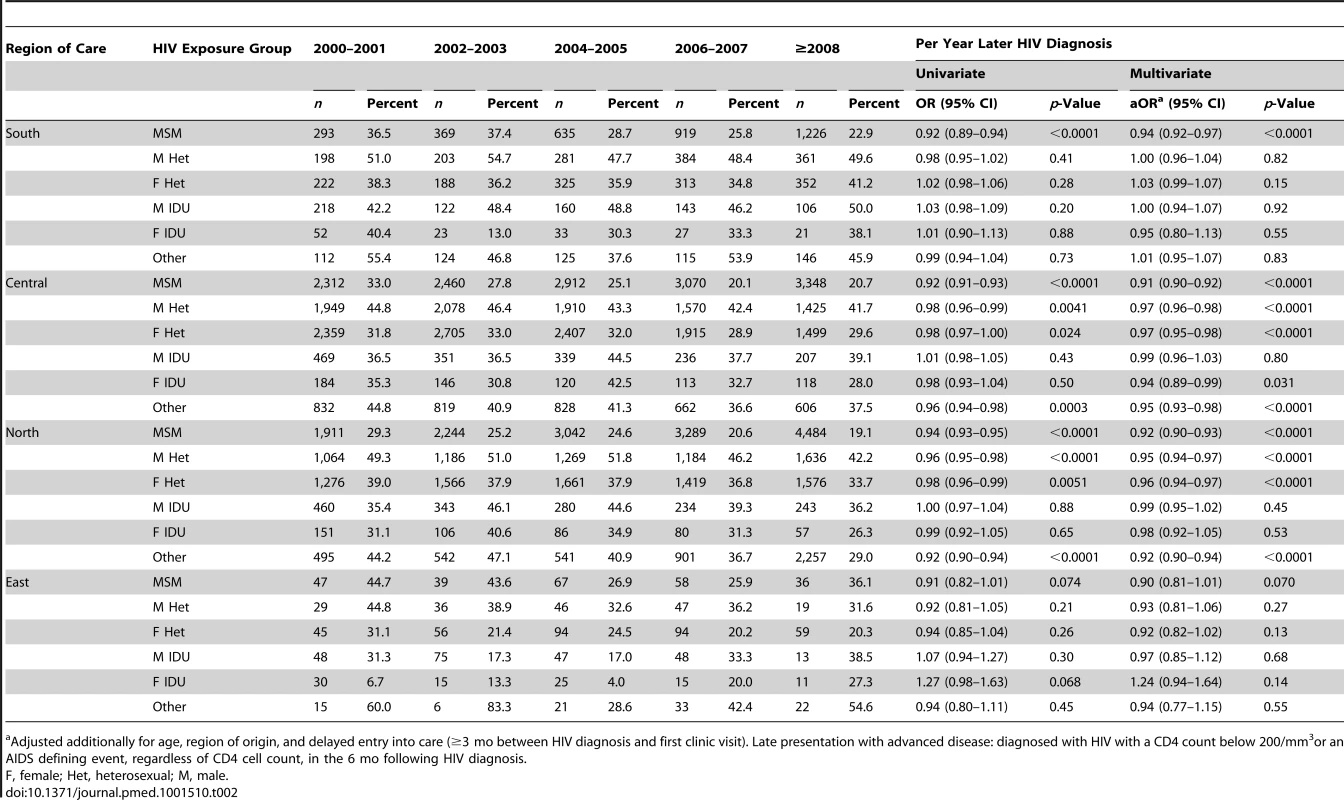

(A) Southern Europe. (B) Central Europe. (C) Northern Europe. (D) Eastern Europe. All models adjusted for age, delayed entry into care (≥3 mo) after HIV diagnosis, region of origin, European region of care, and HIV mode of infection. F, female; Het, heterosexual; M, male. Results for presentation with advanced disease are summarised in Table 2. Within Southern Europe, late presentation with advanced disease decreased in MSMs from 36.5% (107/293) during 2000/2001 to 29.7% (364/1,226)≥2008 (aOR 0.94 per year later; 95% CI 0.92–0.97), but was stable in other infection groups. In Central Europe late presentation with advanced disease was decreasing in all HIV-exposure groups except male IDUs, and most rapidly in MSMs, from 33.0% (763/2,312) to 20.7% (693/3,348; aOR 0.91 per year later; 95% CI 0.90–0.92). Similar results were seen in Northern Europe, with a decrease over time in all HIV-exposure groups except male and female IDUs. There were no significant changes over time in Eastern Europe in the odds of late presentation with advanced disease.

Tab. 2. Percentage of late presenters with advanced disease and adjusted odds of late presentation with advanced disease associated with later calendar years of HIV diagnosis: a comparison across regions and HIV exposure group.

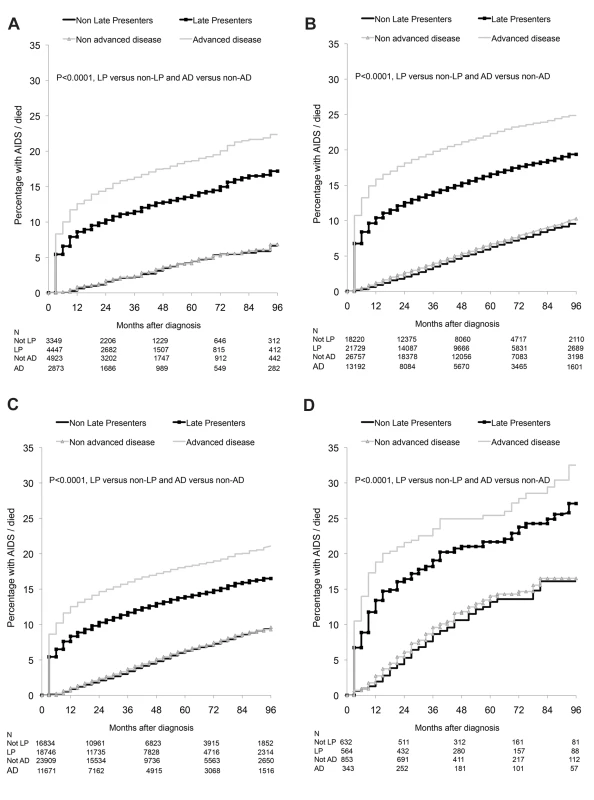

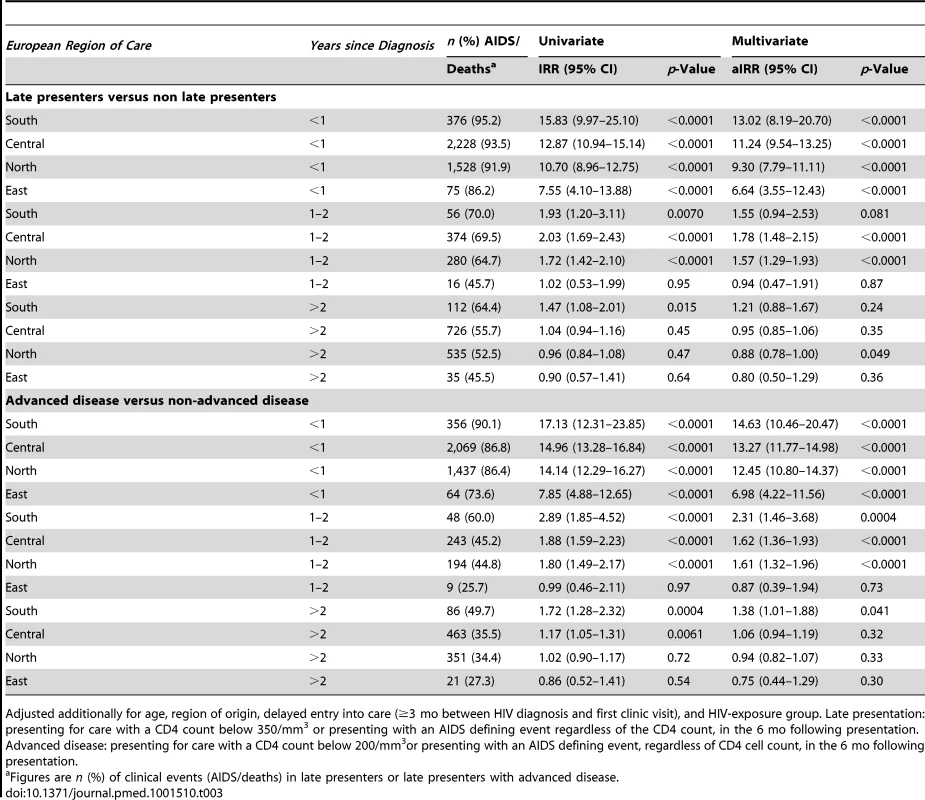

Adjusted additionally for age, region of origin, and delayed entry into care (≥3 mo between HIV diagnosis and first clinic visit). Late presentation with advanced disease: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 200/mm3or an AIDS defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. There were 8,187 AIDS/deaths (1,852 deaths, 6,283 AIDS, 52 AIDS/death on the same date) during 327,003 person-years of follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier probability of progression to AIDS/death stratified by late presentation and late presentation with advanced disease is shown in Figures 3A–3D. Late presenters or late presenters with advanced disease within each region had a steep increase in probability of new AIDS/death within the first 1 or 2 y following presentation, but followed a similar curve as those who did present late after this period, with some differences between regions (p<0.0001, test for interaction).

Fig. 3. (A–D) Progression to new AIDS/death: role of late presentation or late presentation with advanced disease: COHERE 2000–2011.

(A) Southern Europe. (B) Central Europe. (C) Northern Europe. (D) Eastern Europe. LP, diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 350/mm3 or an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Presentation with advanced disease (AD): diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 200/mm3 or an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. This finding is explored in Table 3. Late presentation was associated with the highest rate of AIDS/death in the first year after HIV diagnosis among persons from Southern Europe (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 13.02; 95% CI 8.19–20.70) and the lowest rate in Eastern Europe (aIRR 6.64; 95% CI 3.55–12.43). In the second year after diagnosis, late presentation was associated with a higher rate of AIDS/death among persons from Southern, Central, and Northern Europe, but was similar in both late and non-late presenters from Eastern Europe. Late presentation was not associated with an increased rate of AIDS/death after the initial 2 y, within any European region of care. Also shown are the results for late presentation with advanced disease, which showed very similar findings. Late presentation was associated with an increased rate of AIDS/death in those presenting with advanced disease beyond 2 y in Southern Europe (aIRR 1.38; 95% CI 1.01–1.88), and only in the first year after diagnosis for those from Eastern Europe (aIRR 6.98; 95% CI 4.22–11.56). Results were similar when excluding patients with unknown or delayed entry into care (Table S4).

Tab. 3. Number and percentage of AIDS/deaths and adjusted incidence rate ratios of AIDS/death after HIV diagnosis in COHERE 2000–2011; late presenters versus non late presenters stratified by European region of care and time since presentation.

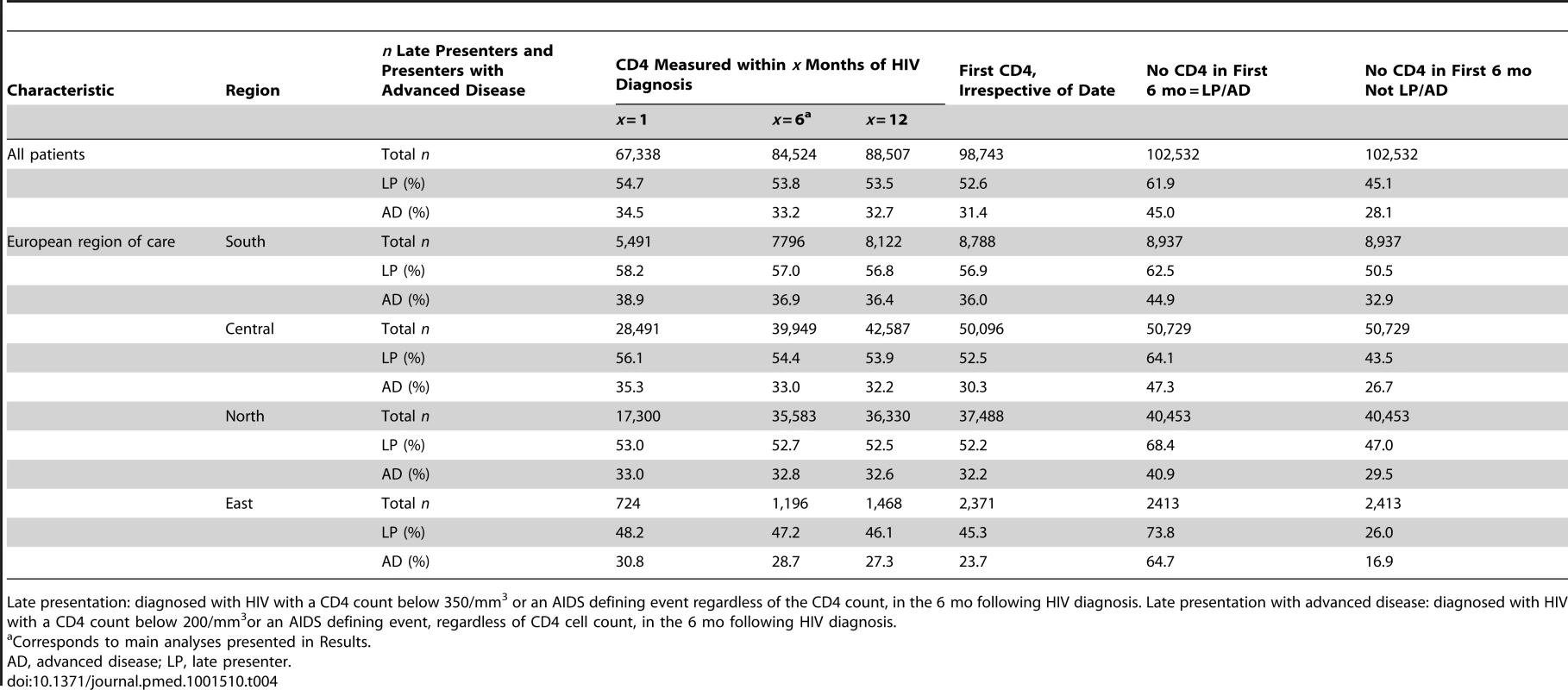

Adjusted additionally for age, region of origin, delayed entry into care (≥3 mo between HIV diagnosis and first clinic visit), and HIV-exposure group. Late presentation: presenting for care with a CD4 count below 350/mm3 or presenting with an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following presentation. Advanced disease: presenting for care with a CD4 count below 200/mm3or presenting with an AIDS defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count, in the 6 mo following presentation. The definition of late presentation or presentation with advanced disease required that a CD4 count was measured within 6 mo of diagnosis. Table S5 considers the odds of having missing CD4 count data, which was consistently higher in Eastern Europe compared to Southern Europe in all HIV-exposure groups. The proportion of late presenters and late presenters with advanced disease varied quite widely, especially in Eastern Europe, as shown in sensitivity analyses in Table 4. Changing the requirement for the CD4 count to be measured within 1 mo or 12 mo of diagnosis did not greatly alter the proportion of late presenters or late presenters with advanced disease, while assuming those without a CD4 count were late presenters increased the proportion of late presenters to 61.9% overall (63,467/102,532) and 73.8% in Eastern Europe (1,781/2,413). Conversely, assuming that those without a CD4 count and without AIDS were not late presenters lowered the proportion of late presenters to 45.1% overall (46,242/102,532) and to 26.0% in Eastern Europe (627/2,413).

Tab. 4. Sensitivity analyses showing the proportion of late presenters or late presenters with advanced disease using different inclusion criteria for CD4 count at HIV diagnosis: COHERE 2000–2011.

Late presentation: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 350/mm3 or an AIDS defining event regardless of the CD4 count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Late presentation with advanced disease: diagnosed with HIV with a CD4 count below 200/mm3or an AIDS defining event, regardless of CD4 cell count, in the 6 mo following HIV diagnosis. Discussion

This study included almost 85,000 persons diagnosed with HIV across Europe after 1 January 2000 and found over half were late presenters and one-third presented with advanced disease using the HIV in Europe definition [2]. The study focused on regional differences within HIV exposure groups, providing important information for health care providers and for future testing initiatives. Overall, late presentation decreased, and especially in MSMs. However, late presentation remains a significant issue across Europe and in all HIV exposure groups. Late presentation increased in male IDUs and female heterosexuals from Southern and IDUs in Eastern Europe. Late presentation was associated with an increased rate of AIDS/deaths, particularly in the first year after HIV diagnosis, although this also varied across Europe. Earlier and more widespread testing, timely referrals after testing positive, as well as improved retention in care strategies are required to further reduce the incidence of late presentation.

The prevalence of late presentation was similar to that reported from other recent European studies [14]–[17], as is the decrease in late presentation [18],[19]. Our study is unique in its ability to report continent-wide changes within HIV exposure groups over a significant period of time. The decreases in late presentation are likely associated with changes to provider initiated HIV testing policies and the massive scale-up of antenatal screening for HIV [20],[21]. Factors associated with late presentation in this and previous studies included non-MSMs HIV-exposure group [1],[5],[14],[16],[17],[22], older age [1],[14],[16]–[19],[23], and non-European origin [14],[17],[19],[22],[24]. Reasons for the increase in late presentation among IDUs in Eastern Europe and heterosexual females and male IDUs from Southern Europe may include suboptimal health care offered to these populations, differences in characteristics that we were unable to adjust for, such as socioeconomic status, the pattern of the underlying epidemic, and appearance of symptoms that may ultimately promote presentation for care [25],[26]. Not all persons recommended for testing undergo testing for a variety of reasons, including stigmatisation, discrimination, criminalisation laws, lack of knowledge, or perceived risk [12]. Not testing inevitably leads to later presentation and initiation of ART, despite the fact that an alarmingly high proportion of the late presenters have been in contact with the health system in the years preceding HIV diagnosis [19],[27].

As reported by others, late presentation or presentation with advanced disease was associated with a significantly increased incidence of AIDS/deaths [28],[29]. We found an increased incidence of AIDS/death, particularly in the first year after HIV diagnosis [6],[18],[30]. There was also significant regional variation, with a 13-fold increased rate in persons in care in Southern Europe and a 6-fold increased rate in Eastern Europe. There was a small increased rate of AIDS/death associated with late presentation in the second year after diagnosis, with the exception of Eastern Europe, and no differences after this time. Morbidity and mortality among HIV-positive individuals in Eastern Europe has been reported to be particularly poor in EuroSIDA [31], the only contributor to COHERE with data from Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, COHERE does not have additional data on factors such as whether individuals are current IDUs, on opiate substitution therapy, or alcohol dependant, all of which may contribute to clinical progression after HIV diagnosis and which likely vary significantly across regions.

Collaborations such as the HIV in Europe initiative have helped raise awareness of HIV testing, and developed an indicator disease testing strategy, whereby all persons presenting for care for a number of indicator diseases are routinely tested for HIV [27]. Despite this and other strategies, individuals continue to test late for HIV with consequences in terms of a poor prognosis, an increased risk of onward HIV transmission, increased costs to the health system, and suboptimal benefits of ART [2],[32]. Increasing awareness of HIV risk factors, increased opportunities for testing, reducing barriers to testing, and increasing the availability of effective ART will help address ongoing HIV transmission across Europe, and especially in Eastern Europe where the number of newly diagnosed infections continues to be very high [33].

Persons were required to have a CD4 count measured within 6 mo of presentation to be included in analyses. If those with missing CD4 counts were assumed late presenters, the proportion of late presenters rose to 62% overall and 74% in Eastern Europe, with 45% overall and 65% from Eastern Europe having advanced disease. Accurate information on CD4 count at presentation is essential for monitoring late presentation, a recent report suggested 18 of 28 countries routinely monitored CD4 count at presentation, and only 11 had information on at least 50% of persons testing HIV positive [34]. Missing CD4 counts were consistently more likely in persons from Eastern Europe (Table S4) among all HIV exposure categories. Persons from Eastern Europe were exclusively included from the EuroSIDA cohort (details at www.cphiv.dk). Participating sites are typically centres of excellence, likely not representative of all persons in the region [35]. Further, inclusion criteria include a pre-booked clinic outpatient appointment, meaning persons have to survive long enough to be recruited to EuroSIDA, which may have excluded a number of late presenters. Persons from Eastern Europe are known to have a poor prognosis [31], and CD4 count may be more likely to be missing in those who die before a CD4 count is measured [36]. As a result, we are likely underestimating the proportion of and consequences of late presentation in this region.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. Date of HIV infection was assumed to be the date of first clinic visit or enrolment into the participating cohort. We performed sensitivity analyses excluding patients where HIV-test date was not reported to COHERE with highly consistent results (Tables S2 and S3). Late presentation and delayed entry into care can be thought of as two distinct issues with different risk factors, interventions, and outcomes [1],[19],[37]. Late presentation reflects patients who are unaware of their HIV infection and do not test until their CD4 count has declined, while delayed entry into care reflects persons who are aware of their HIV status but chose not to seek care for their HIV. Less than 10% of our patient population had delayed entry into care, although this information was only available for a minority of patients. We excluded cohorts including only seroconverters from our analyses, because persons in these cohorts are unlikely to be late presenters. However, inclusion of these cohorts did not substantially alter our findings (Table S2). Local regulations meant information on ethnic origin was not available for over 40% of persons, and likely includes a significant number of migrants who are known to present later for testing [32].

In summary, while late presentation has decreased over time across Europe, it remains a significant issue across the European continent with implications for both individuals and the public health in most European regions. Late presentation was associated with an increased rate of AIDS/death, particularly in the first year after HIV diagnosis. It is important that earlier HIV testing strategies are targeted to all populations at risk both within the health care system and in community based programs, to ensure timely referrals after testing positive, improved retention in care strategies, and optimal clinical management and initiation of ART in those testing HIV positive.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. GirardiE, AloisiMS, AriciC, PezzottiP, SerrainoD, et al. (2004) Delayed presentation and late testing for HIV: demographic and behavioral risk factors in a multicenter study in Italy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 36 : 951–959.

2. AntinoriA, CoenenT, CostagiolaD, DedesN, EllefsonM, et al. (2011) Late presentation of HIV infection: a consensus definition. HIV Med 12 : 61–64.

3. World Health Organization (2010) Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach. – 2010 revision. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2013.

4. BattegayM, FluckigerU, HirschelB, FurrerH (2007) Late presentation of HIV-infected individuals. Antivir Ther 12 : 841–851.

5. SabinCA, SmithCJ, GumleyH, MurphyG, LampeFC, et al. (2004) Late presenters in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: uptake of and responses to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 18 : 2145–2151.

6. LanoyE, Mary-KrauseM, TattevinP, PerbostI, Poizot-MartinI, et al. (2007) Frequency, determinants and consequences of delayed access to care for HIV infection in France. Antivir Ther 12 : 89–96.

7. QuinnTC, WawerMJ, SewankamboN, SerwaddaD, LiC, et al. (2000) Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med 342 : 921–929.

8. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2010) HIV testing: increasing uptake and effectiveness in the European Union. Available: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/101129_GUI_HIV_testing.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2013.

9. KrentzHB, GillJ (2010) Despite CD4 cell count rebound the higher initial costs of medical care for HIV-infected patients persist 5 years after presentation with CD4 cell counts less than 350 mul. AIDS 24 : 2750–2753.

10. FleishmanJA, YehiaBR, MooreRD, GeboKA (2010) The economic burden of late entry into medical care for patients with HIV infection. Med Care 48 : 1071–1079.

11. DeblondeJ, DeKP, HamersFF, FontaineJ, LuchtersS, et al. (2010) Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 20 : 422–432.

12. YazdanpanahY, LangeJ, GerstoftJ, CairnsG (2010) Earlier testing for HIV–how do we prevent late presentation? Antivir Ther 15 Suppl 1 : 17–24.

13. KjaerJ, LedergerberB (2004) HIV cohort collaborations: proposal for harmonization of data exchange. Antivir Ther 9 : 631–633.

14. ZoufalyA, van derHM, MarcusU, HoffmannC, StellbrinkH, et al. (2012) Late presentation for HIV diagnosis and care in Germany. HIV Med 13 : 172–181.

15. d'ArminioMA, Cozzi-LepriA, GirardiE, CastagnaA, MussiniC, et al. (2011) Late presenters in new HIV diagnoses from an Italian cohort of HIV-infected patients: prevalence and clinical outcome. Antivir Ther 16 : 1103–1112.

16. CamoniL, RaimondoM, RegineV, SalfaMC, SuligoiB (2013) Late presenters among persons with a new HIV diagnosis in Italy, 2010–2011. BMC Public Health 13 : 281.

17. VivesN, Carnicer-PontD, Garcia deOP, CampsN, EsteveA, et al. (2012) Factors associated with late presentation of HIV infection in Catalonia, Spain. Int J STD AIDS 23 : 475–480.

18. HellebergM, EngsigFN, KronborgG, LaursenAL, PedersenG, et al. (2012) Late presenters, repeated testing, and missed opportunities in a Danish nationwide HIV cohort. Scand J Infect Dis 44 : 282–288.

19. NdiayeB, SalleronJ, VincentA, BatailleP, BonnevieF, et al. (2011) Factors associated with presentation to care with advanced HIV disease in Brussels and Northern France: 1997–2007. BMC Infect Dis 11 : 11.

20. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO RegionalOffice for Europe (2009) HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2009. Available: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/publications/101129_sur_hiv_2009.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2013.

21. World Health Organization (2007) Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595568_eng.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2013.

22. de OlallaPG, ManzardoC, SambeatMA, OcanaI, KnobelH, et al. (2011) Epidemiological characteristics and predictors of late presentation of HIV infection in Barcelona (Spain) during the period 2001–2009. AIDS Res Ther 8 : 22.

23. CastillaJ, SobrinoP, De La FuenteL, NoguerI, GuerraL, et al. (2002) Late diagnosis of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: consequences for AIDS incidence. AIDS 16 : 1945–1951.

24. CouturierE, SchwoebelV, MichonC, HubertJB, DelmasMC, et al. (1998) Determinants of delayed diagnosis of HIV infection in France, 1993–1995. AIDS 12 : 795–800.

25. MathersBM, DegenhardtL, AliH, WiessingL, HickmanM, et al. (2010) HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet 375 : 1014–1028.

26. DicksonN, McAllisterS, SharplesK, PaulC (2012) Late presentation of HIV infection among adults in New Zealand: 2005–2010. HIV Med 13 : 182–189.

27. SullivanAK, RabenD, ReekieJ, RaymentM, MocroftA, et al. (2013) Feasibility and effectiveness of indicator condition-guided testing for HIV: results from HIDES I (HIV Indicator Diseases across Europe Study). PLoS One 8: e52845 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052845

28. ChadbornTR, DelpechVC, SabinCA, SinkaK, EvansBG (2006) The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals (England and Wales, 2000–2004). AIDS 20 : 2371–2379.

29. SametJH, FreedbergKA, SteinMD, LewisR, SavetskyJ, et al. (1998) Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med 158 : 734–740.

30. DelpierreC, Lauwers-CancesV, PuglieseP, Poizot-MartinI, BillaudE, et al. (2008) Characteristics trends, mortality and morbidity in persons newly diagnosed HIV positive during the last decade: the profile of new HIV diagnosed people. Eur J Public Health 18 : 345–347.

31. ReekieJ, KowalskaJD, KarpovI, RockstrohJ, KarlssonA, et al. (2012) Regional differences in AIDS and non-AIDS related mortality in HIV-positive individuals across Europe and Argentina: the EuroSIDA study. PLoS One 7: e41673 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041673

32. GirardiE, SabinCA, MonforteAD (2007) Late diagnosis of HIV infection: epidemiological features, consequences and strategies to encourage earlier testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 46 Suppl 1: S3–S8.

33. JolleyE, RhodesT, PlattL, HopeV, LatypovA, et al. (2012) HIV among people who inject drugs in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: a systematic review with implications for policy. BMJ Open 2.

34. Likatavicius G, van de Laar MJ (2011) HIV infection and AIDS in the European Union and European Economic Area, 2010. Euro Surveill 16. Available: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/images/dynamic/EE/V16N48/art20030.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2013.

35. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic (2012). Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2013.

36. JohnsonM, SabinC, GirardiE (2010) Definition and epidemiology of late presentation in Europe. Antivir Ther 15 Suppl 1 : 3–8.

37. TurnerBJ, CunninghamWE, DuanN, AndersenRM, ShapiroMF, et al. (2000) Delayed medical care after diagnosis in a US national probability sample of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med 160 : 2614–2622.

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2013 Číslo 9- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Ferinject: správně indikovat, správně podat, správně vykázat

- Magnosolv v neurologické ambulantní praxi (MUDr. Veronika Hořenínová, Interna-neurologie s. r. o., Praha 1)

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Adherence to Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention: A Substudy Cohort within a Clinical Trial of Serodiscordant Couples in East Africa

- Translating Cochrane Reviews to Ensure that Healthcare Decision-Making is Informed by High-Quality Research Evidence

- Physician Emigration from Sub-Saharan Africa to the United States: Analysis of the 2011 AMA Physician Masterfile

- Acupuncture and Counselling for Depression in Primary Care: A Randomised Controlled Trial

- Serotype-Specific Changes in Invasive Pneumococcal Disease after Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Introduction: A Pooled Analysis of Multiple Surveillance Sites

- Risk Factors and Outcomes for Late Presentation for HIV-Positive Persons in Europe: Results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE)

- Current and Former Smoking and Risk for Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Postmarket Surveillance of Medical Devices: A Comparison of Strategies in the US, EU, Japan, and China

- Feasibility of Mass Vaccination Campaign with Oral Cholera Vaccines in Response to an Outbreak in Guinea

- Preconception Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: New Opportunities and a New Metric

- How to Stir Up Trouble…while Riding a Rollercoaster

- Health Workforce Brain Drain: From Denouncing the Challenge to Solving the Problem

- Association of the ANRS-12126 Male Circumcision Project with HIV Levels among Men in a South African Township: Evaluation of Effectiveness using Cross-sectional Surveys

- Setting Research Priorities for Preconception Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Aiming to Reduce Maternal and Child Mortality and Morbidity

- Transnational Tobacco Company Interests in Smokeless Tobacco in Europe: Analysis of Internal Industry Documents and Contemporary Industry Materials

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Postmarket Surveillance of Medical Devices: A Comparison of Strategies in the US, EU, Japan, and China

- Translating Cochrane Reviews to Ensure that Healthcare Decision-Making is Informed by High-Quality Research Evidence

- Physician Emigration from Sub-Saharan Africa to the United States: Analysis of the 2011 AMA Physician Masterfile

- Current and Former Smoking and Risk for Venous Thromboembolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání