-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaA Public Health Framework for Legalized Retail Marijuana Based on the US Experience: Avoiding a New Tobacco Industry

Rachel Barry and Stanton Glantz argue that a public health framework that prioritizes public health over business interests should be used by US states and countries that legalize retail marijuana.

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 13(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002131

Category: Policy Forum

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002131Summary

Rachel Barry and Stanton Glantz argue that a public health framework that prioritizes public health over business interests should be used by US states and countries that legalize retail marijuana.

Summary Points

The US states that have legalized retail marijuana are using US alcohol policies as a model for regulating retail marijuana, which prioritizes business interests over public health.

The history of major multinational corporations using aggressive marketing strategies to increase and sustain tobacco and alcohol use illustrates the risks of corporate domination of a legalized marijuana market.

To protect public health, marijuana should be treated like tobacco, not as the US treats alcohol: legal but subject to a robust demand reduction program modeled on successful evidence-based tobacco control programs.

Because marijuana is illegal in most places, jurisdictions worldwide (including other US states) considering legalization can learn from the US experience to shape regulations that prioritize public health over profits.

Introduction

While illegal in the United States, marijuana use has been increasing since 2007 [1]. In response to political campaigns to legalize retail sales, by 2016 four US states (Colorado, Washington, Alaska, and Oregon) had enacted citizen initiatives to implement regulatory frameworks for marijuana, modeled on US alcohol policies [2], where state agencies issue licenses to and regulate private marijuana businesses [2,3,4]. Arguments for legalization have stressed the negative impact marijuana criminalization has had on social justice, public safety, and the economy [5]. Uruguay, an international leader in tobacco control [6], became the first country to legalize the sale of marijuana in 2014, and, as of July 2016, was implementing a state monopoly for marijuana production and distribution [7]. None of the US laws [2], or pending proposals in other states [8], prioritize public health. Because marijuana is illegal in most places, jurisdictions worldwide (including other US states) considering legalization can learn from the US experience to shape regulations that favor public health over profits.

In contrast, while legal, US tobacco use has been declining [1]. To protect public health, marijuana should be treated like tobacco, legal but subject to a robust demand reduction program modeled on evidence-based tobacco control programs [9] before a large industry (akin to tobacco [10]) develops and takes control of the market and regulatory environment [11].

Likely Effect of Marijuana Commercialization on Public Health

While the harms of marijuana do not currently approach those of tobacco [12], the extent to which legal restrictions on marijuana may have functioned to limit these harms is unknown. Currently, regular heavy marijuana use is uncommon, and few users become lifetime marijuana smokers [13]. However, marijuana use is not without risk. The risk for developing marijuana dependence (25%) is lower than for nicotine addiction (67%) and higher than for alcohol dependence (16%) [14], but is still substantial, with rising numbers of marijuana users in high-income countries seeking treatment [15]. Reversing the historic pattern, in some places, marijuana has become a gateway to tobacco and nicotine addiction [15].

This situation will likely change as legal barriers that have kept major corporations out of the market [10] are removed. Unlike small-scale growers and marijuana retailers, large corporations seek profits through consolidation, market expansion, product engineering, international branding, and promotion of heavy use to maximize sales, and use lobbying, campaign contributions, and public relations to create a favorable regulatory environment [2,11,16,17,18,19]. By 2016, US marijuana companies had developed highly potent products [15] and were advertising via the Internet [11] and developing marketing strategies to rebrand marijuana for a more sophisticated audience [20]. Without effective controls in place, it is likely that a large marijuana industry, akin to tobacco and alcohol, will quickly emerge and work to manipulate regulatory frameworks and use aggressive marketing strategies to increase and sustain marijuana use [10,11] with a corresponding increase in social and health costs.

Public perception of the low risk of marijuana [21] is discordant with available evidence. Marijuana smoke has a similar toxicity profile as tobacco smoke [22] and, regardless of whether marijuana is more or less dangerous than tobacco, it is not harmless [2]. The California Environmental Protection Agency has identified marijuana smoke as a cause of cancer [23], and marijuana smokers are at increased risk of respiratory disease [24,25]. Epidemiological studies in Europe have found associations between smoking marijuana and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, and stroke in young adults [15,26]. One minute of exposure to marijuana smoke significantly impairs vascular function in a rat model [27]. In humans, impaired vascular function is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes including atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction [27,28,29].

Acute risks associated with highly potent marijuana products (i.e., cannabinoid concentrates, edibles) include anxiety, panic attacks, and hallucinations [15]. Other health risks associated with use include long-lasting detrimental changes in cognitive function [13,15], poor educational outcomes, accidental childhood ingestion and adult intoxication [26], and auto fatalities [30,31].

US Alcohol Policy Is Not a Good Model for Regulating Marijuana

The fact that US marijuana legalization is modeled on US alcohol policies is not reassuring. In 2014, 61% of US college students (age 18–25) reported using alcohol in the past 30 days, compared to 19% for marijuana and 13% for tobacco [32]. Binge drinking is a serious problem, with 41% of young Americans reporting heavy episodic drinking in the past year [33].

Aggressive alcohol marketing likely contributes to this pattern [34]. Even though the alcohol industry’s voluntary rules prohibit advertising on broadcast, cable, radio, print, and digital communications if more than 30% of the audience is under age 21, this standard permits them to advertise in media outlets with substantial youth audiences [35], including Sports Illustrated and Rolling Stone, resulting in American youth (ages 12–20) being exposed to 45% more beer and 27% more spirits advertisements than legal drinking-aged adults [36]. If such alcohol marketing regulations were applied universally to marijuana, consumption would likely be higher, not lower, than it is now [26].

Using a Public Health Framework from Evidence-Based Tobacco Control to Regulate Retail Marijuana

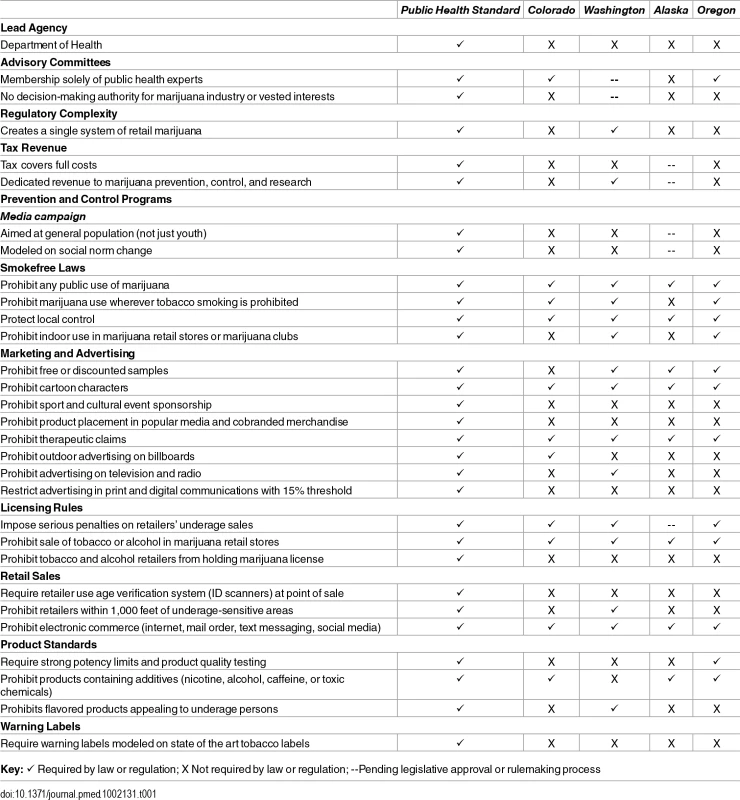

Table 1 compares the situation in the four US states that have legalized retail marijuana to a public health standard based on successes and failures in tobacco and alcohol control. A public health framework for marijuana legalization would designate the health department as the lead agency with, like tobacco, a mandate to protect the public by minimizing all (not just youth) use. The health department would implement policies to protect nonusers, prevent initiation, and encourage users to quit, as well as regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of marijuana products, with other agencies (such as tax authorities) playing supporting roles.

Tab. 1. Public health framework versus state marijuana regulations.

Key: ✓ Required by law or regulation; X Not required by law or regulation; --Pending legislative approval or rulemaking process Because public health regulations are often in direct conflict with the interests of profit-driven corporations [19], it is important to protect the policy process from industry influence. In contrast to what states that have legalized retail marijuana have done to date, a public health framework would require that expert advisory committees involved in regulatory oversight and public education policymaking processes consist solely of public health officials and experts and limit the marijuana industry’s role in decision-making to participation as a member of the “public.” Including the tobacco industry on advisory committees when developing tobacco regulations blocks, delays, and weakens public health policies [37]. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, a global public health treaty ratified by 180 parties as of April 2016, recognizes the need to protect the policymaking process from industry interference:

“[Governments] should not allow any person employed by the tobacco industry or any entity working to further its interests to be a member of any government body, committee or advisory group that sets or implements tobacco control or public health policy.” [37, Article 5.3]

A marijuana regulatory framework that prioritizes public health would have similar provisions.

A public health framework would avoid regulatory complexity that favors corporations with financial resources to hire lawyers and lobbyists to create and manipulate weak or unenforceable policies [11]. To simplify regulatory efforts, including licensing enforcement, implementation of underage access laws, prevention and education programs, and taxation, a public health framework would create a unitary market, in which all legal sales, regardless of whether use is intended for recreational or medical purposes, follow the same rules [38]. Unlike Colorado, Oregon, and Alaska, in 2015, Washington State accomplished this public health goal when it merged its retail and medical markets [39].

Earmarked funds to support comprehensive prevention and control programs over time, which are not included in the four US states’ regulatory regimes, will be critical to reduce marijuana prevalence, marijuana-related diseases, and costs arising from marijuana use. A public health framework would set taxes high enough to discourage use and cover the full cost of legalization, including a broad-based marijuana prevention and control program. Using a public health approach, the prevention program would implement social norm change strategies, modeled on evidence-based tobacco control programs, aimed at the population as a whole—not just users or youth [9]. Demand reduction strategies applied to marijuana would include: 1) countering pro-marijuana business influence in the community; 2) reducing exposure to secondhand marijuana smoke and aerosol and other marijuana products (including protecting workers vulnerable to these exposures); 3) controlling availability of marijuana and marijuana products; and 4) promoting services to help marijuana users quit.

A public health framework would protect the public from secondhand smoke exposure by including marijuana in existing national and local smokefree laws for tobacco products, including e-cigarettes. Local governments would have authority to adopt stronger regulations than the state or nation. There would be no exemptions for indoor use in hospitality venues, marijuana retail stores, or lounges, including for “vaped” marijuana.

To protect the public from industry strategies to increase and sustain marijuana use, a public health framework would prohibit or severely restrict (within constitutional limitations) marketing and advertising, including prohibitions on free or discounted samples, the use of cartoon characters, event sponsorship, product placement in popular media, cobranded merchandise, and therapeutic claims (unless approved by the government agency that regulates such claims). Marketing would be prohibited on television, radio, billboards, and public transit and restricted in print and digital communications (e.g., internet and social media) with the percentage of youth between ages 12 and 20 as the maximum underage audience composition for permitted advertising (roughly 15% in the US) [35]. These advertising restrictions are justified and would likely pass US Constitutional muster because they are implemented for important public health purposes, are evidence-based [35], and have worked to promote similar goals in other contexts. Legal sellers of the newly legal marijuana products would be permitted to communicate relevant product information to their legal adult customers.

A scenario in which a public health regulatory framework is applied to marijuana would require licensees to pay for strong licensing provisions for retailers, with active enforcement and license revocation for underage sales. As has been done in the four US states (Table 1), outlets would be limited to the sale of marijuana only to avoid the proliferation and normalization of sales in convenience stores or “big box” retailers. No retailer that sold tobacco or alcohol would be granted a license to sell marijuana products. Based on best public health practices for tobacco retailers [40], marijuana retail stores would be prohibited within 1,000 feet of underage-sensitive areas including postsecondary schools, with limits on new licenses in areas that already have a significant number of retail outlets. Electronic commerce, including internet, mail order, text messaging, and social media sales, would be prohibited because these forms of nontraditional sales are difficult to regulate, age-verification is practically impossible [41], and they can easily avoid taxation [42].

Central to a public health framework would be assigning the health department with the authority to enact strong potency limits, dosage, serving size, and product quality testing for marijuana and marijuana products (e.g., edibles, tinctures, oils), with a clear mission to protect public health. Additives that could increase potency, toxicity, or addictive potential, or that would create unsafe combinations with other psychoactive substances, including nicotine and alcohol, would be illegal. Unlike US restrictions on marijuana products, flavors (that largely appeal to children), would be prohibited.

A public health model applied to marijuana would include health warning labels that follow state-of-the-art tobacco requirements implemented in several countries outside of the United States, including Uruguay, Brazil, Canada, and Australia [43]. Public health-oriented labels would: 1) be large, (at least 50% of packaging) on front and back and not limited to the sides, prominently featured, and contain dissuasive imagery in addition to text; 2) be clear and direct and communicate accurate information to the user regarding health risks associated with marijuana use and secondhand exposure; and 3) use language appropriate for low-literacy adults. Health messages would include risk of dependence [2], cardiovascular [2,44,45], respiratory [25], and neurological disease [46], and cancer [23], and would warn against driving a vehicle or operating equipment, as well as the risks of co-use with tobacco or alcohol.

While there is already adequate scientific evidence to raise concern about a wide range of adverse health effects, there is more to learn. Earmarked funds from marijuana taxes would also provide an ongoing revenue stream for research that would guide marijuana prevention and control efforts and mitigate the human and economic costs of marijuana use, as well as better define medical uses as the basis for proper regulation of marijuana for therapeutic purposes.

Avoiding a Private Market

Privatizing tobacco and alcohol sales leads to intensified marketing efforts, lower prices, more effective distribution, and an industry that will aggressively oppose any public health effort to control use [47,48]. Avoiding a privatized marijuana market and the associated pressures to increase consumption in order to maximize profits would likely lead to lower consumer demand, consumption, and prevalence, even among youth, and would reduce the associated public health harm [49].

Governments may avoid marijuana commercialization by implementing a state monopoly over its production and distribution, similar to Uruguay’s regulatory structure for marijuana [3,50] and to the Nordic countries’ alcohol control systems [51], which are designed to protect public health over maximizing government revenue. The state would have more control over access, price, and product characteristics (including youth-appealing products or packaging, potency, and additives) and would refrain from marketing that promotes increased use [3,52]. In cases where national laws cause concern about local authority’s ability to adopt government monopolies, a public health authority could be used as an alternative [53].

It is important to avoid intrinsic conflicts of interest created by state ownership. As is the case with state-ownership of tobacco, without specific policies to prioritize public health, a state’s desire to increase revenue often supersedes public health goals to minimize use [51,52]. Beyond mitigating potential conflicts of interest inherent in state monopolies, a public health framework for marijuana would instruct the government agency that manages the monopoly to minimize individual consumption in order to maximize public health at the population level. (Similar public health goals are explicit in Nordic alcohol monopolies [51].)

While a state monopoly is an effective approach to protect public health [51,54], in practice, however, even the strongest government monopolies for alcohol (i.e., Nordic Countries) have been eroded over time by multinational companies that argue such controls are illegal protectionism under international and regional trade agreements [4,51]. While trade agreements have been used to threaten tobacco control and other public health policies [55], clearly identifying protection of public health as the goal of the state monopoly would make it more difficult to challenge these controls, especially if sales revenues were used to help fund evidence-based demand reduction policies [49] (Table 1).

Conclusion

It is important that jurisdictions worldwide learn from the US experience and implement, concurrently with full legalization, a public health framework for marijuana that minimizes consumption to maximize public health (Table 1). A key goal of the public health framework would be to make it harder for a new, wealthy, and powerful marijuana industry to manipulate the policy environment and thwart public health efforts to minimize use and associated health problems.

Zdroje

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

2. Hall W, Weier M (2015) Assessing the Public Health Impacts of Legalizing Recreational Cannabis Use in the USA. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 97 : 607–615.

3. Room R (2014) Legalizing a Market for Cannabis for Pleasure: Colorado, Washington, Uruguay and Beyond. Addiction 109 : 345–351. doi: 10.1111/add.12355 24180513

4. Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K (2010) Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy (2nd Ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

5. Weitzer R (2014) Legalizing Recreational Marijuana: Comparing Ballot Outcomes in Four States. J Qual Crim Justice Criminol 2.

6. World Health Organization (2014) Global Progress Report on Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

7. Watts J (2013) Uruguay's Likely Cannabis Law Could Set Tone for War on Drugs in Latin America. The Guardian.

8. ArcView Market Research, New Frontier (2016) The State of Legal Marijuana Markets 4th Edition.

9. Shibuya K, Ciecierski C, Guindon E, Bettcher DW, Evans DB, Murray CJ, et al. (2003) WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Development of an Evidence Based Global Public Health Treaty. BMJ 327 : 154–157. 12869461

10. Barry RA, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA (2014) Waiting for the Opportune Moment: The Tobacco Industry and Marijuana Legalization. Milbank Quarterly 92 : 207–242. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12055 24890245

11. Richter KP, Levy S (2014) Big Marijuana—Lessons from Big Tobacco. New England Journal of Medicine 371 : 399–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1406074 24918955

12. Imtiaz S, Shield KD, Roerecke M, Cheng J, Popova S, Kurdyak P, et al. (2016) The Burden of Disease Attributable to Cannabis Use in Canada in 2012. Addiction 111 : 653–662. doi: 10.1111/add.13237 26598973

13. Auer R, Vittinghoff E, Yaffe K, Kunzi A, Kertesz SG, Levine DA, et al. (2016) Association between Lifetime Marijuana Use and Cognitive Function in Middle Age: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (Cardia) Study. JAMA Intern Med 176 : 352–361. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7841 26831916

14. Cougle JR, Hakes JK, Macatee RJ, Zvolensky MJ, Chavarria J (2016) Probability and Correlates of Dependence among Regular Users of Alcohol, Nicotine, Cannabis, and Cocaine: Concurrent and Prospective Analyses of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 77: e444–450. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09469 27137428

15. World Health Organization. The Health and Social Effects of Nonmedical Cannabis Use. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/cannabis_report/en/. Accessed 16 Aug 2016

16. Jernigan DH (2009) The Global Alcohol Industry: An Overview. Addiction 104 : 6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02430.x 19133910

17. Cook PJ (2007) Paying the Tab: The Economics of Alcohol Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. xiii, 262 p. p.

18. Hastings G (2012) Why Corporate Power Is a Public Health Priority. BMJ 345: e5124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5124 22915664

19. Freudenberg N (2012) The Manufacture of Lifestyle: The Role of Corporations in Unhealthy Living. Journal of Public Health Policy 33 : 244–256. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2011.60 22258282

20. Krupnik M (2016) High Times and Agency Unite to Sell Marijuana to Mainstream. New York Times. New York.

21. Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, Lewis M, Wang Y, Windle M, et al. (2015) Perceived Harm, Addictiveness, and Social Acceptability of Tobacco Products and Marijuana among Young Adults: Marijuana, Hookah, and Electronic Cigarettes Win. Subst Use Misuse 50 : 79–89. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.958857 25268294

22. Moir D, Rickert WS, Levasseur G, Larose Y, Maertens R, White P, et al. (2008) A Comparison of Mainstream and Sidestream Marijuana and Tobacco Cigarette Smoke Produced under Two Machine Smoking Conditions. Chem Res Toxicol 21 : 494–502. 18062674

23. Reproductive and Cancer Hazard Assessment Branch, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, California Environmental Protection Agency (2009) Evidence on the Carcinogenicity of Marijuana Smoke. Sacramento, Ca.

24. Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR (2014) Adverse Health Effects of Marijuana Use. N Engl J Med 371 : 879.

25. Owen KP, Sutter ME, Albertson TE (2014) Marijuana: Respiratory Tract Effects. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 46 : 65–81. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8374-y 23715638

26. Hall W, Lynskey M (2016) Evaluating the Public Health Impacts of Legalizing Recreational Cannabis Use in the USA. Addiction.

27. Yeboah J, Crouse J, Hsu F, Burke G, Herrington D (2007) Brachial Flow-Mediated Dilation Predicts Incident Cardiovascular Events in Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 115 : 2390–2397. 17452608

28. Yeboah J, Sutton-Tyrrell K, McBurnie M, Burke G, Herrington D, Crouse J (2008) Association between Brachial Artery Reactivity and Cardiovascular Disease Status in an Elderly Cohort: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Atheroschlerosis 197.

29. Yeboah J, Folsom A, Burke G, Johnson C, Polak J, Post W, et al. (2009) Predictive Value of Brachial Flow-Mediated Dilation for Incident Cardiovascular Events in a Population-Based Study: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation 120 : 502–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864801 19635967

30. Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetz G, Spurgin A, Pierce RS, Gorelick DA, et al. (2016) Cannabis Effects on Driving Longitudinal Control with and without Alcohol. J Appl Toxicol.

31. Rogeberg O, Elvik R (2016) The Effects of Cannabis Intoxication on Motor Vehicle Collision Revisited and Revised. Addiction.

32. Haardörfer R, Berg C, Lewis M, McDonald B, Pillai D. Polytobacco, Alcohol, and Marijuana Use Patterns in College Students: A Latent Class Analysis. https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.srnt.org/resource/resmgr/Conferences/2016_Annual_Meeting/Program/61820_SRNT_Program_web.pdf. (Accessed July 6)

33. Evans-Polce R, Lanza S, Maggs J (2016) Heterogeneity of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Substance Use Behaviors in U.S. College Students: A Latent Class Analysis. Addict Behav 53 : 80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.010 26476004

34. Tanski SE, McClure AC, Li Z, Jackson K, Morgenstern M, Sargent JD (2015) Cued Recall of Alcohol Advertising on Television and Underage Drinking Behavior. JAMA Pediatr 169 : 264–271. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3345 25599526

35. Jernigan DH, Ostroff J, Ross C (2005) Alcohol Advertising and Youth: A Measured Approach. Journal of Public Health Policy 26 : 312–325. 16167559

36. Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth (2002) Overexposed: Youth a Target of Alcohol Advertising in Magazines. Washington D.C.: Institute for Health Care Research and Policy, Georgetown University.

37. Conference of the Parties (2003) WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

38. Murphy P, Carnevale J (2016) Regulating Marijuana in California. Sacramento, CA: Public Policy Institute of California.

39. Washington State Legislature (2015) Bill: Hb2136.

40. Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Berson J, et al. (2000) Investing in Youth Tobacco Control: A Review of Smoking Prevention and Control Strategies. Tob Control 9 : 47–63. 10691758

41. Mosher J (2006) Alcohol Industry Voluntary Regulation of Its Advertising Practices: A Status Report.

42. Chriqui JF, Ribisl KM, Wallace RM, Williams RS, O'Connor JC, el Arculli R (2008) A Comprehensive Review of State Laws Governing Internet and Other Delivery Sales of Cigarettes in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 10 : 253–265. doi: 10.1080/14622200701838232 18236290

43. World Health Organization (2008) Guidelines for Implementation of Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Packaging and Labelling of Tobacco Products).

44. Wang X, Derakhshandeh R, Liu J, Narayan S, Nabavizadeh P, Le S, et al. (2016) One Minute of Marijuana Secondhand Smoke Exposure Substantially Impairs Vascular Endothelial Function. J Am Heart Assoc 5: pii: e003858. doi: 003810.001161/JAHA.003116.003858.

45. Thomas G, Kloner RA, Rezkalla S (2014) Adverse Cardiovascular, Cerebrovascular, and Peripheral Vascular Effects of Marijuana Inhalation: What Cardiologists Need to Know. Am J Cardiol 113 : 187–190. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.042 24176069

46. Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, et al. (2012) Persistent Cannabis Users Show Neuropsychological Decline from Childhood to Midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E2657–2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109 22927402

47. Gilmore AB, Fooks G, McKee M (2011) A Review of the Impacts of Tobacco Industry Privatisation: Implications for Policy. Glob Public Health 6 : 621–642. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.595727 21790502

48. Grubesic TH, Murray AT, Pridemore WA, Tabb LP, Liu Y, Wei R (2012) Alcohol Beverage Control, Privatization and the Geographic Distribution of Alcohol Outlets. BMC Public Health 12 : 1015. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1015 23170899

49. Pratt A (2016) Can State Ownership of the Tobacco Industry Really Advance Tobacco Control? Tob Control 25 : 365–366. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052594 26437809

50. Pardo B (2014) Cannabis Policy Reforms in the Americas: A Comparative Analysis of Colorado, Washington, and Uruguay. Int J Drug Policy 25 : 727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.05.010 24970383

51. Hogg SL, Hill SE, Collin J (2015) State-Ownership of Tobacco Industry: A 'Fundamental Conflict of Interest' or a 'Tremendous Opportunity' for Tobacco Control? Tob Control.

52. Rehm J, Fischer B (2015) Cannabis Legalization with Strict Regulation, the Overall Superior Policy Option for Public Health. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 97 : 541–544.

53. Caulkins J, Kilmer B, Kleinman M, MacCoun R, Midgette G, Oglesby P, et al. (2015) Considering Marijuana Legalization Insights for Vermont and Other Jurisdictions. RAND Institute.

54. Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, Chaloupka FJ, Caulkins JP (2014) Developing Public Health Regulations for Marijuana: Lessons from Alcohol and Tobacco. Am J Public Health 104 : 1021–1028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301766 24825201

55. Crosbie E, Gonzalez M, Glantz SA (2014) Health Preemption Behind Closed Doors: Trade Agreements and Fast-Track Authority. Am J Public Health 104: e7–e13.

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2016 Číslo 9- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Ferinject: správně indikovat, správně podat, správně vykázat

- Optimální dávkování apixabanu v léčbě fibrilace síní

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Reporting of Adverse Events in Published and Unpublished Studies of Health Care Interventions: A Systematic Review

- A Public Health Framework for Legalized Retail Marijuana Based on the US Experience: Avoiding a New Tobacco Industry

- Improving Research into Models of Maternity Care to Inform Decision Making

- Associations between Extending Access to Primary Care and Emergency Department Visits: A Difference-In-Differences Analysis

- Sex Differences in Tuberculosis Burden and Notifications in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use by Breastfeeding HIV-Uninfected Women: A Prospective Short-Term Study of Antiretroviral Excretion in Breast Milk and Infant Absorption

- A Comparison of Midwife-Led and Medical-Led Models of Care and Their Relationship to Adverse Fetal and Neonatal Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study in New Zealand

- Scheduled Intermittent Screening with Rapid Diagnostic Tests and Treatment with Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine versus Intermittent Preventive Therapy with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine for Malaria in Pregnancy in Malawi: An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial

- Tenofovir Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women at Risk of HIV Infection: The Time is Now

- The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity

- International Criteria for Acute Kidney Injury: Advantages and Remaining Challenges

- Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care: Outcomes after Five Years in a Prospective Cohort Study

- Potential for Controlling Cholera Using a Ring Vaccination Strategy: Re-analysis of Data from a Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

- Association between Adult Height and Risk of Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer: Results from Meta-analyses of Prospective Studies and Mendelian Randomization Analyses

- The Incidence Patterns Model to Estimate the Distribution of New HIV Infections in Sub-Saharan Africa: Development and Validation of a Mathematical Model

- Antimicrobial Resistance: Is the World UNprepared?

- A Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Framework for Humanitarian Innovation

- Reduced Emergency Department Utilization after Increased Access to Primary Care

- "The Policy Dystopia Model": Implications for Health Advocates and Democratic Governance

- Interplay between Diagnostic Criteria and Prognostic Accuracy in Chronic Kidney Disease

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Sex Differences in Tuberculosis Burden and Notifications in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- International Criteria for Acute Kidney Injury: Advantages and Remaining Challenges

- Potential for Controlling Cholera Using a Ring Vaccination Strategy: Re-analysis of Data from a Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

- The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Revma Focus: Spondyloartritidy

nový kurz

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání