-

Články

Top novinky

Reklama- Vzdělávání

- Časopisy

Top články

Nové číslo

- Témata

Top novinky

Reklama- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Nové podcasty

Reklama- Kariéra

Doporučené pozice

Reklama- Praxe

Top novinky

ReklamaRoad Trauma in Teenage Male Youth with Childhood Disruptive Behavior Disorders: A Population Based Analysis

Background:

Teenage male drivers contribute to a large number of serious road crashes despite low rates of driving and excellent physical health. We examined the amount of road trauma involving teenage male youth that might be explained by prior disruptive behavior disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder).Methods and Findings:

We conducted a population-based case-control study of consecutive male youth between age 16 and 19 years hospitalized for road trauma (cases) or appendicitis (controls) in Ontario, Canada over 7 years (April 1, 2002 through March 31, 2009). Using universal health care databases, we identified prior psychiatric diagnoses for each individual during the decade before admission. Overall, a total of 3,421 patients were admitted for road trauma (cases) and 3,812 for appendicitis (controls). A history of disruptive behavior disorders was significantly more frequent among trauma patients than controls (767 of 3,421 versus 664 of 3,812), equal to a one-third increase in the relative risk of road trauma (odds ratio = 1.37, 95% confidence interval 1.22–1.54, p<0.001). The risk was evident over a range of settings and after adjustment for measured confounders (odds ratio 1.38, 95% confidence interval 1.21–1.56, p<0.001). The risk explained about one-in-20 crashes, was apparent years before the event, extended to those who died, and persisted among those involved as pedestrians.Conclusions:

Disruptive behavior disorders explain a significant amount of road trauma in teenage male youth. Programs addressing such disorders should be considered to prevent injuries.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: . PLoS Med 7(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000369

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000369Summary

Background:

Teenage male drivers contribute to a large number of serious road crashes despite low rates of driving and excellent physical health. We examined the amount of road trauma involving teenage male youth that might be explained by prior disruptive behavior disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder).Methods and Findings:

We conducted a population-based case-control study of consecutive male youth between age 16 and 19 years hospitalized for road trauma (cases) or appendicitis (controls) in Ontario, Canada over 7 years (April 1, 2002 through March 31, 2009). Using universal health care databases, we identified prior psychiatric diagnoses for each individual during the decade before admission. Overall, a total of 3,421 patients were admitted for road trauma (cases) and 3,812 for appendicitis (controls). A history of disruptive behavior disorders was significantly more frequent among trauma patients than controls (767 of 3,421 versus 664 of 3,812), equal to a one-third increase in the relative risk of road trauma (odds ratio = 1.37, 95% confidence interval 1.22–1.54, p<0.001). The risk was evident over a range of settings and after adjustment for measured confounders (odds ratio 1.38, 95% confidence interval 1.21–1.56, p<0.001). The risk explained about one-in-20 crashes, was apparent years before the event, extended to those who died, and persisted among those involved as pedestrians.Conclusions:

Disruptive behavior disorders explain a significant amount of road trauma in teenage male youth. Programs addressing such disorders should be considered to prevent injuries.

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

Road crashes are a common cause of death, disability, and property loss throughout the world equating to around 2% of the gross national product of the entire global economy [1]. Teenage male drivers are the single most risky demographic group, with an incidence twice the population average [2]–[4]. Teenage male drivers involved in serious crashes can also have especially devastating outcomes related to ongoing needs for health care as well as foregone future productivity [5]. In addition, young drivers are sometimes a hazard to other road users and contribute to more fatalities in older pedestrians than older drivers themselves [6]–[8]. Unfortunately, teenage male drivers are often remarkable in risk attitudes and resistant to standard safety advice [9],[10].

Safety regulation is a countermeasure for preventing road trauma in drivers. For example, most countries prohibit driving before age 16 y [11]–[13]. Some regions have further restrictions using graduated licensing programs that disallow young drivers from night driving, high-speed roadways, and additional hazardous settings [14]–[16]. Regulations based on age are often supplemented by restrictions related to diabetes mellitus, seizure disorders, or other medical illnesses [17]. Regulations have generally not been feasible, however, for curbing many forms of driver inattention contributing to crashes [18]. As a consequence, road trauma is a common cause of death and disability until about age 40 y and indicates that prevailing regulations (and self-restrictions) are insufficient [19],[20].

Past research has suggested that disruptive behavior disorders might contribute to the risk of serious road trauma in teenage males [21]–[24]. The evidence suggests that these disorders are frequent during childhood and adolescence, characterized by impulsivity with rule infringement, and identified in some cases of trauma [25]–[29]. Past studies, however, raise uncertainties because of small sample size, referral bias, surrogate outcomes, inadequate controls, and self-report bias [30],. Authorities, therefore, have called for more research stressing that the full range of disorders is understudied and misunderstood [32]–[34]. The purpose of this study was to avoid such biases and assess how much disruptive behavior disorders predispose teenage males to serious road trauma.

Methods

Setting

Ontario was one of the largest Canadian provinces in 2005 (study midpoint) and had 16,599.8 km of roadway, 246 acute care hospitals, 766 roadway fatalities, and a total population of 12,160,280 individuals (of whom 664,865 were between age 16 and 19 y) [35]–[40]. In this study we used universal health care databases in Canada's single-payer health care system to conduct a population-based retrospective case-control analysis of teenagers involved in serious road trauma between April 1, 2002 and March 31, 2009, representing all years available for analysis. These databases have been validated in past medical research and prior analyses have used these databases to provide measures of relative risks, absolute risk, and attributable risk [41]–[43]. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center.

Patients

Cases were identified as consecutive males between age 16 and 19 y admitted to an acute care hospital for motor vehicle related trauma (codes V01 to V99). Controls were identified as consecutive males in the same age range admitted to the same hospitals during the same time interval for acute appendicitis (codes K35 to K38). We chose this control condition because it was frequent, clearly coded in hospital records, generally unrelated to traumatic injury, not known to protect against other childhood disorders, and has served as a standard for other research [44]–[49]. We excluded teenage girls from both groups to avoid Simpson's paradox (a spurious association created by loading on a null-null position) since this group has much lower rates of crash involvement [50],[51].

Driving

We directed special attention to distinguish different patterns of road trauma. In accord with prior research [52], we characterized each case using four categories: driver, passenger, pedestrian, and miscellaneous. The pedestrian category also included other vulnerable road users (e.g., bicyclists) and the miscellaneous category included unusual events (e.g., skateboards and snowmobiles). We also stratified trauma severity according to medical management by following each patient during hospitalization for surgery, critical care treatment, or death. The available databases contained no data on crash hour, other people in the same collision, or at-fault determinations by police.

Disorders

We focused on selected disorders relevant to childhood, defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and associated with inattention or distraction. The specific disorders were attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder (codes 312 to 314) [53]–[56]. Others use the term “attention deficit related disorders,” “childhood behavioral disorder,” or “externalizing disorder” to denote these conditions since combinations are frequent, exact diagnoses are not always possible, and diagnostic criteria change over time [57]–[60]. We did not examine internalizing disorders characterized by anxiety or excess deliberation such as social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, or anorexia nervosa.

Ascertainment

For both cases and controls, we searched outpatient database records for a decade prior to admission to identify any disruptive behavior disorder diagnosed earlier (after age 5 y). This strategy assured that ascertainment was blind to outcome status, free of reporting bias, and avoided reverse-causality artifacts [61],[62]. This strategy also allowed us to examine complex combinations occurring together, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder combined with substance abuse or another neuropsychiatric condition. These methods have been validated extensively in past research in Canada's single-payer universal health insurance system and were conducted using privacy safeguards of the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Ontario [63].

Severity

We used multiple measures to gauge the severity of each disorder because the available records did not contain results from psychological testing. Age at onset of the disorder was defined as the date first diagnosed by a physician. Intensity of care was defined as the mean number of physician visits per year as well as the total years of treatment for the disorder. Case complexity was also characterized by the total number of visits to a board-certified psychiatrist as well as any mention of substance abuse, learning disorders, depression, personality disorders, epilepsy, movement disorders, or mental developmental delay. The available databases did not contain information on drug therapy, patient adherence, social services, school performance, or special resources.

Validation

We conducted secondary analyses to examine the robustness of our findings. We used three separate tracer conditions to explore whether the risk associated with psychiatric disorders was distinct and not shared by other childhood illnesses; namely, asthma (code 493), contact dermatitis (code 692), and otitis media (codes 381 to 382). The purpose of these analyses was to check for the absence of an association where no association would be expected [64]. In addition, we stratified patients according to their short-term medical outcomes; namely, those patients who had a prolonged length of stay (>7 d), critical care unit admission, surgical operation, or death. The purpose of these analyses was to check how findings extended across a spectrum of increasing trauma severity.

Statistics

The primary analysis examined the prevalence of prior disruptive behavior disorders among cases involved in a crash compared to controls not involved in a crash using an unpaired chi-square test congruent with the case-control design [65]. Logistic regression was used to further quantify associations using odds ratios to adjust for imbalances in demographic characteristics (age, social status, home location) and prior neuropsychiatric diagnoses (each coded separately). Logistic regression was also used to explore additional risk factors among patients positive for a prior disorder. Calculations of attributable risk and attributable fraction were conducted using population-based methods [66].

Results

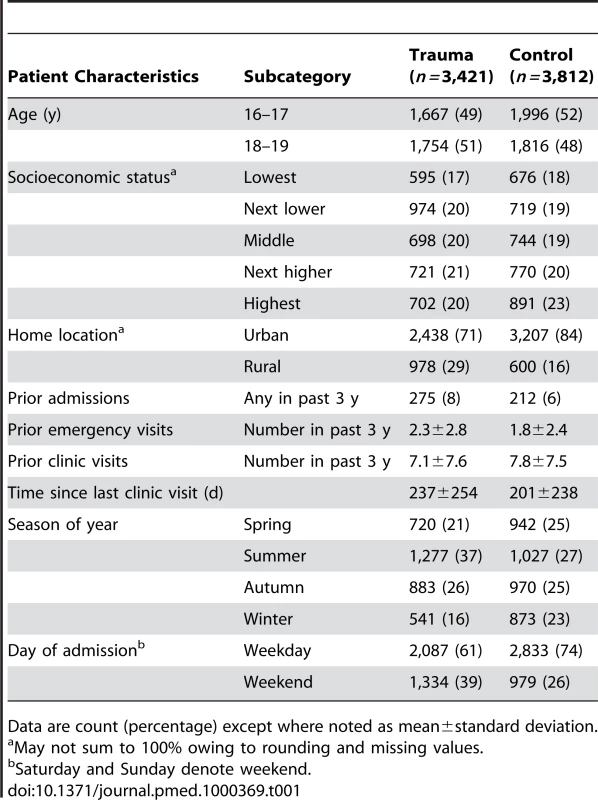

During the 7-y interval a total of 3,421 emergency admissions occurred for 3,421 teenage male patients involved in road trauma over 146 hospitals and 1,445 attending physicians. We observed no major trends over the years. The typical patient had a mean age of 17.6 y, was a driver (71%, n = 2,443), and had been traveling on a public roadway (61%, n = 2,070). Almost all had visited a physician during the decade before hospital admission (98%, n = 3,356). A large number lived in rural areas (29%, n = 978), crashed on a weekend (39%, n = 1,334), involved another vehicle (40%, n = 1,368), and presented in the summer (37%, n = 1,277). In comparison, 3,812 control patients were admitted for acute appendicitis over the same interval and same hospitals (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Patient characteristics.

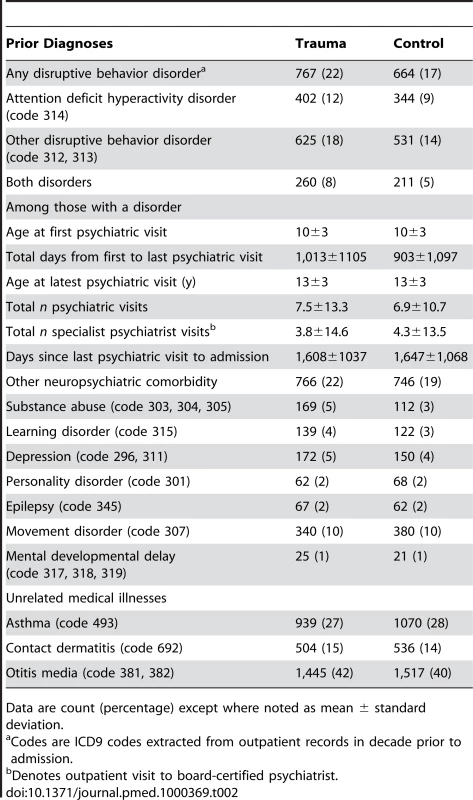

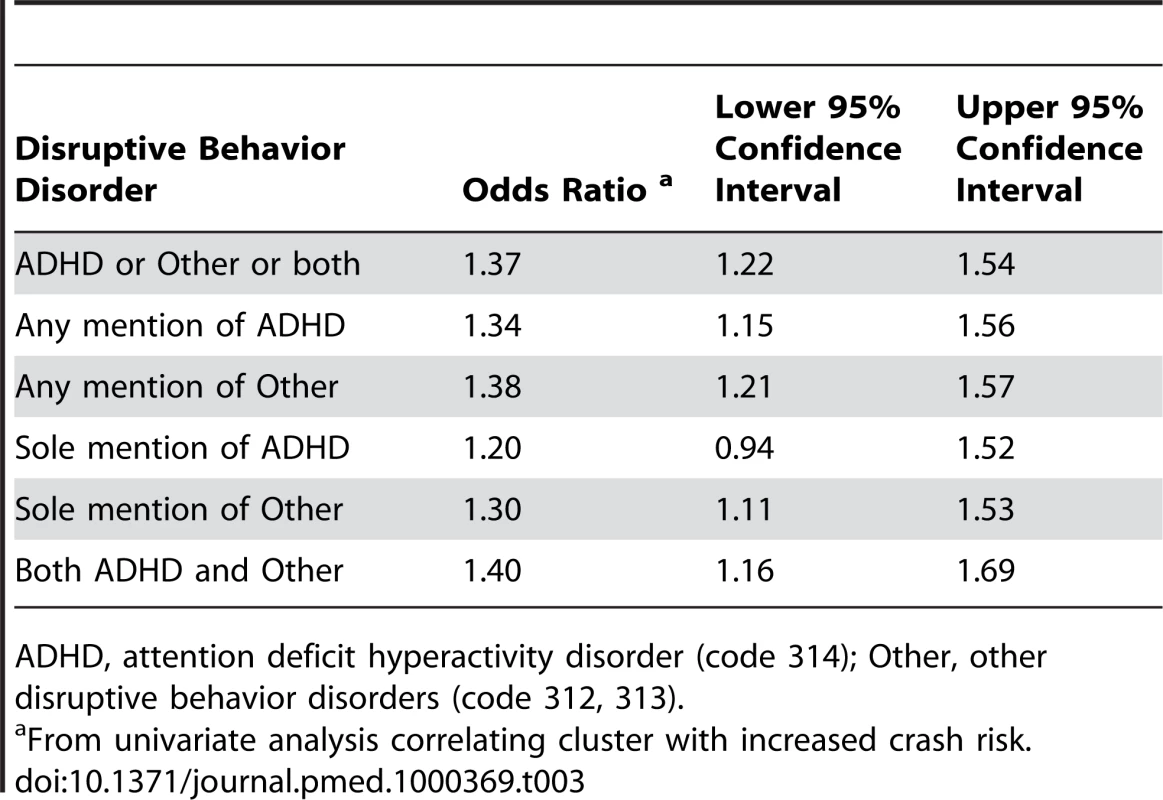

Data are count (percentage) except where noted as mean±standard deviation. A history of a prior disruptive behavior disorder was significantly more common among cases than controls (Table 2). Based on the case-control design, this association was equal to a one-third increase in the risk of road trauma (odds ratio 1.37, 95% confidence interval 1.22–1.54, chi-square = 28, p<0.001). The increased trauma risk was evident for those with a history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a history of other disruptive behavior disorder, or both types of histories clustered together (Table 3). In contrast, no adverse association was observed with a history of asthma (odds ratio 0.97, 95% confidence interval 0.87–1.07). Similarly, no major association was observed with a history of contact dermatitis (odds ratio 1.06, 95% confidence interval 0.93–1.20) or otitis media (odds ratio 1.10, 95% confidence interval 1.01–1.22).

Tab. 2. Prior diagnoses.

Data are count (percentage) except where noted as mean ± standard deviation. Tab. 3. Crash risk according to cluster of disruptive behavior disorders.

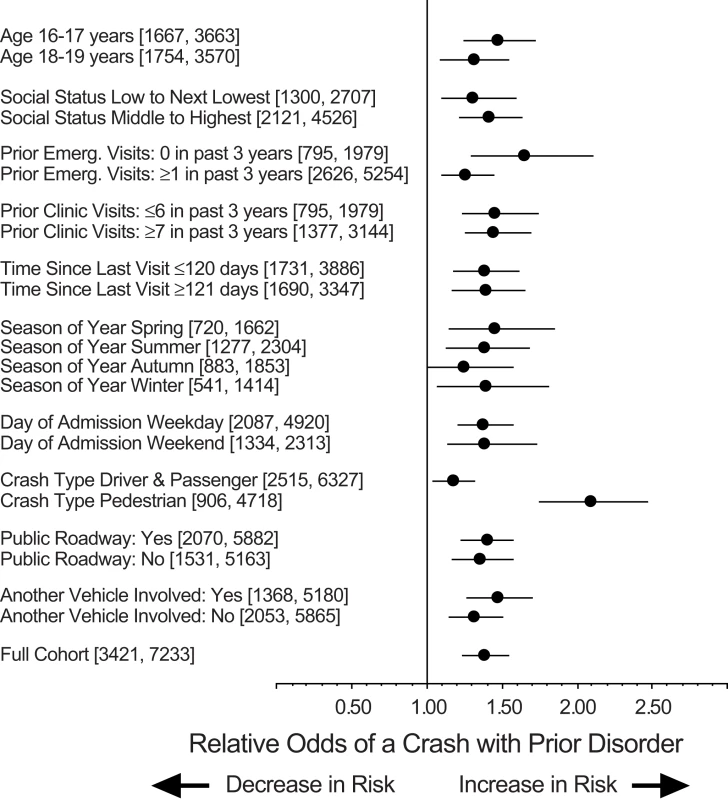

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (code 314); Other, other disruptive behavior disorders (code 312, 313). The association of disruptive behavior disorders and increased risk of trauma was consistent for patients with different characteristics (Figure 1). Most subgroups overlapped the primary analysis and no subgroup showed a contrary pattern. The increased risk was apparent in crashes that did or did not involve another vehicle and was not accentuated for crashes during weekends or summer months (unlike crashes due to alcohol). The largest increase was observed in the subgroup analysis of pedestrians that showed a doubling of risk. Multivariable analysis adjusting for demographic characteristics (age, social status, home location) and neuropsychiatric comorbidities showed a somewhat larger increase in the risk of road trauma associated with prior disorders (odds ratio = 1.38, 95% confidence interval 1.21–1.56, p<0.001).

Fig. 1. Crash risk in different subgroups.

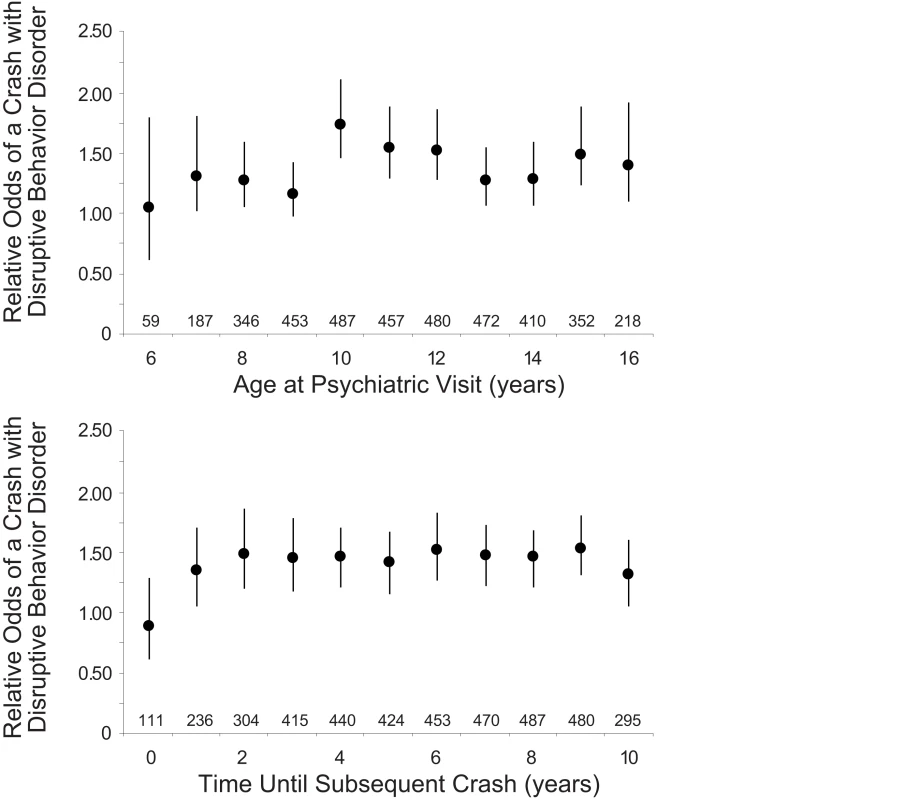

Each analysis examines correlation of a history of a disruptive behavior disorder with higher relative risk of a crash. Event counts and sample size for each subgroup appear in square brackets. Results expressed as odds ratio (solid circle) and 95% confidence interval (horizontal line). Analyses of crash type, public roadway, and other vehicle involvement based on all controls. Results for full cohort appear at bottom and show odds ratio of 1.37 with 95% confidence interval 1.22–1.54. Two aspects of the patient history accentuated the observed association as independent risk factors for trauma among those with prior disruptive behavior disorders. Those in rural settings with prior disorders had double the risk of those in urban settings with no prior disorders (odds ratio = 2.35, 95% confidence interval 1.83–3.01). Similarly, those treated for five or more years had higher risks compared to those with no prior disorders (odds ratio = 1.43, 95% confidence interval 1.26–1.63). Age at first diagnosis, number of specialist visits, and other neuropsychiatric comorbidities were not particularly ominous or reassuring (Table S1). The increased risk was apparent multiple years before the crash as measured either by time from birth or time before crash (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Timing of prior psychiatric visit and crash risk.

Each analysis examines correlation of psychiatric visit for a disruptive behavior disorder with higher relative risk of a crash. Estimates calculated in 1-y intervals based on whether patient had any psychiatric visit during corresponding year. Upper panel for patient age at visit and lower panel for time from visit to subsequent crash. Numbers above horizontal axis denote count of patients with a visit during interval. Findings expressed as odds ratio (solid circle) and 95% confidence interval (vertical line). Results show increases years before the crash and potential maximum at age 10 y. We found no evidence that the severity of injury was different in patients with disruptive behavior disorders. A total of 1,904 of the 3,421 trauma patients underwent surgery, with a rate similar for those with disorders and those without disorders (54% versus 56%, p = 0.415). A total of 879 trauma patients required critical care treatment, with a rate similar for those with disorders and those without disorders (24% versus 26%, p = 0.132). A total of 716 trauma patients stayed in hospital more than a week, with a rate similar for those with disorders and those without disorders (20% versus 21%, p = 0.510). A total of 70 trauma patients died, with a rate similar for those with disorders and those without disorders (2.1% versus 2.0%, p = 0.930).

Discussion

We studied teenage male youth admitted to hospital for road trauma. We found high rates of disruptive behavior disorders evident years before the crash. Overall, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder were associated with about a one-third increase in the risk of serious road trauma, which is similar in magnitude to the relative risk documented for individuals treated for epilepsy [67],[68]. Collectively, the attributable risk associated with these disorders explained about 1-in-20 crashes observed in this study. These findings were prevalent throughout the years, accentuated in rural settings, evident in the most severe cases, and difficult to attribute to chance.

One limitation in our study relates to the retrospective design. Teenagers and their families are aware of diagnoses, may self-restrict driving, and thereby attenuate all observed risks [69]. In addition, childhood psychiatric diagnoses can be mistaken and the misdiagnoses also bias our relative risk estimates toward the null [55],[70]. For example, if diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were each 95%, the true odds ratio would be about 2.0 rather than 1.3. Our controls, furthermore, were not immune to psychiatric illness, so that the attributable risk estimates are also conservative. If our study presumed a disease prevalence of 10% from population surveys [71], for example, the estimated odds ratio would be about 2.5 and the attributable risk would account for about 1-in-9 observed crashes.

Another large limitation in our study is that all patients diagnosed with disruptive behavior disorders had access to care and received treatment. Because care is effective, the observed increase in risk is smaller than would occur in patients with missed diagnoses, no access to care, or poor adherence to treatment. The Canadian setting also had multimodal social services during this interval devoted to educating families of affected children, adapting school programs for special needs, curbing alcohol drinking in youth, and subsidizing medications for children in poverty [72],[73]. If 50% of eligible patients received treatment and 50% of treated patients responded with positive benefits, for example, the true unmeasured baseline risk would equal an odds ratio of about 1.5 rather than 1.3.

A third limitation that causes our study to underestimate the association of disruptive behavior disorders with road trauma is that the data excluded girls [74]. To address this issue we retrieved the original databases, replicated our methods in girls rather than boys, and conducted a post hoc analysis. As anticipated, the results yielded a smaller sample (n = 4,156) and about the same estimated risk (odds ratio 1.31, 95% confidence interval 1.07–1.61, chi-square = 6.8, p = 0.010). Hence, the association of disruptive behavioral disorders with road trauma extended to both teenage boys and girls. Of course, many issues remain for future research including medication level at time of injury, amount of driving, extent of brain trauma, and sequelae among those not hospitalized [75],[76].

Universal health care databases have strengths because they are the antithesis of small surveys using self-report. The sample size is substantial and represents a 100% response rate—thereby avoiding referral bias, selective participation, range restrictions, and other threats to validity. Outcomes reflect serious crashes and are not extrapolations based on surrogate tests of driving risk. Ascertainment of prior diagnoses is conducted in an objective manner blind to outcomes, free of recall bias, and comprehensive over a decade. The downside, however, is a lack of data from prospective observation of lifestyle, alcohol, drugs, speeding, distractions, impulsivity, undiagnosed internalizing disorders, and other mechanisms or mediators in the causal pathway to driver error [77].

The increased risk of road trauma associated with disruptive behavior disorders in male youth does not by itself justify withholding a driver's license. Many disorders can be treated effectively, so that well-managed patients could have outcomes similar to the population average [78],[79]. This study, as well, has no at-fault data so an alternative interpretation might be that such disorders merely impair a person's ability to avoid a mishap initiated by someone else. Our analysis could also be explained by a hidden third factor linked to both the disorder and crash risks; for example, undocumented head injuries. Most importantly, the observed increase in risk as pedestrians indicates that those who abstain from driving do not escape the danger of serious road trauma.

The strongest argument in favor of regulations is that bad driving imposes risks on other people and can destroy whole lives in a moment. The main rebuttal against regulations involves the reduced quality of life and increased workload for innocent individuals. Reporting by physicians of unfit drivers to vehicle licensing authorities is one policy option, particularly since the average patient in our study had multiple visits to a physician in the year before the trauma [80]. Regulations of psychiatric diagnoses, however, would be controversial given the unfair stigma and social discrimination that surrounds mental disorders [81]. A further caveat is that disruptive behavior disorders are sometimes overdiagnosed, open to debate, and could be abused by vehicle insurers [82],[83].

Roadway engineering is a different alternative for mitigating driver error by making the environment more forgiving. However, such well-intentioned policies sometimes lead to greater dangers for younger drivers [84]. A classic example involves designing the approach paths to road intersections with generous sight lines to accommodate drivers with slow reaction times (e.g., older drivers). This safety cushion, ironically, can tempt drivers who have quick reaction times to approach at faster speeds (e.g., younger drivers) [85]. As such, a policy of creating “forgiving roads” can ironically create “permissive roads” for those who are impulsive and have imperfect rule adherence. The underlying error is that drivers sometimes overestimate their skills and underestimate their risks [86].

The findings call attention to a widespread, preventable, and costly cause of death and disability. Specifically, disruptive behavior disorders could be considered as contributors to road trauma—analogous to seizure disorders, refraction errors, and some other medical diseases [17]. Greater attention by primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and community health workers might be helpful since interventions can perhaps reduce the risk including medical treatments (e.g., methylphenidate), avoidance of distractions (e.g., cell phone calls while driving), and basic practicalities (e.g., abstaining from alcohol). Most people know that teenage males are prone to traffic injuries, but the current data show that prevailing adjustments are not sufficient.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. World Health Organization 2009 Global status report on road safety: time for action. Geneva World Health Organization

2. ToroyanT

PedenM

2007 Youth and road safety. Geneva World Health Organization 5 13

3. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2007 Traffic safety facts: 2007 - young drivers. Washington, D.C. US Department of Transportation 1 2

4. Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators 2007 Canadian motor vehicle traffic collision statistics. Ottawa Transport Canada 6

5. KlonoffH

ClarkC

KlonoffPS

1993 Long-term outcome of head injuries: a 23 year follow up study of children with head injuries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 56 410 415

6. EvansL

2000 Risks older drivers face themselves and threats they pose to other road users. Int J Epidemiol 29 315 322

7. EvansL

2007 Drivers involved in crashes killing older road users. Warrendale: Society of Automotive Engineers. Report 2007-01-1165

8. ConstantA

LagardeE

2010 Protecting vulnerable road users from injury. PLoS Med 7 e1000228 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000228

9. SteinbergL

2004 Risk taking in adolescence: what changes, and why? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1021 51 58

10. LeverenceRR

MartinezM

WhislerS

Romero-LeggottV

HarjiF

2005 Does office-based counseling of adolescents and young adults improve self-reported safety habits? A randomized controlled effectiveness trial. J Adolesc Health 36 523 528

11. Wikipedia contributors 2010 Minimum driving age. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_driving_age. Accessed 25 September 2010.

12. The Joint OECD/ECMT Transport Research Centre 2006 Young drivers: the road to safety. Paris Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and European Conference of Ministers of Transport

13. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety 2008 Licensing teenagers later reduces their crashes. Status Report 42 1 4

14. WilliamsAF

MayhewDR

2008 Graduated licensing and beyond. Am J Prev Med 35 S324 S333

15. WilliamsAF

2009 Licensing age and teenage driver crashes: a review of the evidence. Traffic Inj Prev 10 9 15

16. SimpsonHM

2003 The evolution and effectiveness of graduated licensing. J Safety Res 34 25 34

17. Canadian Medical Association 2006 Determining medical fitness to operate motor vehicles: CMA driver guide. 7th edition. Ottawa Canadian Medical Association

18. LamLT

2002 Distractions and the risk of car crash injury: the effect of drivers' age. J Safety Res 33 411 419

19. Bureau of the Census 2009 Statistical abstract of the United States 2009: the national data book. D.C: Government Printing Office [Table 114]

20. PLoS Medicine 2010 Preventing road deaths—time for data. PLoS Med 7 e1000257 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000257

21. MeadowsML

StradlingSG

LawsonS

1998 The role of social deviance and violations in predicting road traffic accidents in a sample of young offenders. Br J Psychol 89) Pt 3 417 431

22. BarkleyRA

MurphyKR

DupaulGI

BushT

2002 Driving in young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: knowledge, performance, adverse outcomes, and the role of executive functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 8 655 672

23. JeromeL

HabinskiL

SegalA

2006 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and driving risk: a review of the literature and a methodological critique. Curr Psychiatry Rep 8 416 426

24. PalkG

DaveyJ

FreemanJ

2007 Prevalence and characteristics of alcohol-related incidents requiring police attendance. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 68 575 581

25. FischerM

BarkleyRA

SmallishL

FletcherK

2007 Hyperactive children as young adults: driving abilities, safe driving behavior, and adverse driving outcomes. Accid Anal Prev 39 94 105

26. JokelaM

PowerC

KivimakiM

2009 Childhood problem behaviors and injury risk over the life course. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50 1541 1549

27. OlofssonE

BunketorpO

AnderssonAL

2009 Children and adolescents injured in traffic—associated psychological consequences: a literature review. Acta Paediatr 98 17 22

28. KesslerRC

AdlerL

BarkleyR

BiedermanJ

ConnersCK

2006 The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 163 716 723

29. HwangSW

ColantonioA

ChiuS

TolomiczenkoG

KissA

2008 The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people. CMAJ 179 779 784

30. JeromeL

SegalA

HabinskiL

2006 What we know about ADHD and driving risk: a literature review, meta-analysis and critique. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15 105 125

31. BarkleyRA

CoxD

2007 A review of driving risks and impairments associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effects of stimulant medication on driving performance. J Safety Res 38 113 128

32. ShepherdJ

FarringtonD

PottsJ

2004 Impact of antisocial lifestyle on health. J Public Health (Oxf) 26 347 352

33. Nova Scotia Nunn Commission of Inquiry 2006 Spiraling out of control: lessons learned from a boy in trouble: report of the Nunn Commission of Inquiry. Supreme Court of Nova Scotia 272

34. KielingRR

SzobotCM

MatteB

CoelhoRS

KielingC

2010 Mental disorders and delivery motorcycle drivers (motoboys): a dangerous association. Eur Psychiatry Jun 8. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20538435. Accessed 25 September 2010.

35. Ontario Ministry of Transportation 2009 Provincial highways: traffic volumes 1988-2006. Toronto Ontario Ministry of Transportation

36. Ontario Ministry of Transportation 2009 Ontario road safety: annual report. Toronto Service Ontario Publications 36

37. Ramage-MorinPL

2008 Motor vehicle accident deaths, 1979 to 2004. Health Rep 19 45 51

38. Minister of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Communities 2008 Transportation Canada 2008: an overview addendum. Ottawa Minister of Public Works and Government Services Report T1-10/2008E

39. EmeryPC

MayhewDR

SimpsonHM

2008 Youth and road crashes: magnitude, characteristics, and trends. Ottawa Traffic Injury Research Foundation

40. Statistics Canada 2007 2006 Census of Population. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Catalogue 97-551-XCB2006009

41. BellCM

RedelmeierDA

2001 Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med 345 663 668

42. RedelmeierDA

DruckerA

VenkateshV

2005 Major trauma in pregnant women during the summer. J Trauma 59 112 116

43. RapoportMJ

HerrmannN

MolnarF

RochonPA

JuurlinkDN

2008 Psychotropic medications and motor vehicle collisions in patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 56 1968 1970

44. RothrockSG

PaganeJ

2000 Acute appendicitis in children: emergency department diagnosis and management. Ann Emerg Med 36 39 51

45. Al-OmranM

MamdaniM

McLeodRS

2003 Epidemiologic features of acute appendicitis in Ontario, Canada. Can J Surg 46 263 268

46. HariharanS

PomerantzW

2008 Correlation between hospitalization for pharmaceutical ingestion and attention deficit disorder in children aged 5 to 9 years old. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 47 15 20

47. MaxsonRT

LawsonKA

PopR

Yuma-GuerreroP

JohnsonKM

2009 Screening for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a select sample of injured and uninjured pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg 44 743 748

48. CallaghanRC

KhizarA

2009 The incidence of cardiovascular morbidity among patients with bipolar disorder: a population-based longitudinal study in Ontario, Canada. J Affect Disord 122 118 123

49. von EybenFE

MouritsenE

HolmJ

MontvilasP

DimcevskiG

2002 Smoking, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, fibrinogen and myocardial infarction before 41 years of age: a Danish case-control study. J Cardiovasc Risk 9 171 178

50. BakerSG

KramerBS

2001 Good for women, good for men, bad for people: Simpson's paradox and the importance of sex-specific analysis in observational studies. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 10 867 872

51. KronmanAC

FreundKM

HanchateA

EmanuelEJ

AshAS

2010 Nursing home residence confounds gender differences in Medicare utilization an example of Simpson's paradox. Womens Health Issues 20 105 113

52. RedelmeierDA

StewartCL

2003 Driving fatalities on Super Bowl Sunday. N Engl J Med 348 368 369

53. BiedermanJ

FaraoneSV

WeberW

RussellRL

RaterM

1997 Correspondence between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36 1682 1687

54. SwansonJM

SergeantJA

TaylorE

Sonuga-BarkeEJ

JensenPS

1998 Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperkinetic disorder. Lancet 351 429 433

55. SorensenMJ

MorsO

ThomsenPH

2005 DSM-IV or ICD-10-DCR diagnoses in child and adolescent psychiatry: does it matter? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 14 335 340

56. RoweR

MaughanB

CostelloEJ

AngoldA

2005 Defining oppositional defiant disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46 1309 1316

57. LamLT

2002 Attention deficit disorder and hospitalization due to injury among older adolescents in New South Wales, Australia. J Atten Disord 6 77 82

58. BruceB

KirklandS

WaschbuschD

2007 The relationship between childhood behaviour disorders and unintentional injury events. Paediatr Child Health 12 749 754

59. MosterD

LieRT

MarkestadT

2008 Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med 359 262 273

60. MerrillRM

LyonJL

BakerRK

GrenLH

2009 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and increased risk of injury. Adv Med Sci 54 20 26

61. Park-WyllieLY

JuurlinkDN

KoppA

ShahBR

StukelTA

2006 Outpatient gatifloxacin therapy and dysglycemia in older adults. N Engl J Med 354 1352 1361

62. JackeviciusCA

TuJV

DemersV

MeloM

CoxJ

2008 Cardiovascular outcomes after a change in prescription policy for clopidogrel. N Engl J Med 359 1802 1810

63. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences 2010 Available: http://www.ices.on.ca. Accessed 25 September 2010.

64. LipsitchM

Tchetgen TchetgenE

CohenT

2010 Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 21 383 388

65. GordisL

2004 Epidemiology. Philadelphia Elsevier Saunders 181 187

66. GordisL

2004 Epidemiology. Philadelphia Elsevier Saunders 191 196

67. HansotiaP

BrosteSK

1991 The effect of epilepsy or diabetes mellitus on the risk of automobile accidents. N Engl J Med 324 22 26

68. DrazkowskiJ

2007 An overview of epilepsy and driving. Epilepsia 48 Suppl 9 10 12

69. SweeneyM

2004 Travel patterns of older Americans with disabilities. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Report 2004-001-OAS

70. DuffySW

WarwickJ

WilliamsAR

KeshavarzH

KaffashianF

2004 A simple model for potential use with a misclassified binary outcome in epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 58 712 717

71. SgroM

RobertsW

GrossmanS

BarozzinoT

2000 School board survey of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Prevalence of diagnosis and stimulant medication therapy. Paediatr Child Health 5 19 23

72. Centre for ADD/ADHD Advocacy, Canada 2010 Available: http://www.caddac.ca. Accessed 25 September 2010.

73. Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance 2010 Available: http://www.caddra.ca. Accessed 25 September 2010.

74. Nada-RajaS

LangleyJD

McGeeR

WilliamsSM

BeggDJ

1997 Inattentive and hyperactive behaviors and driving offenses in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36 515 522

75. WoodwardLJ

FergussonDM

HorwoodLJ

2000 Driving outcomes of young people with attentional difficulties in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39 627 634

76. CoxDJ

Taylor-DavisM

2009 Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and driving safety.

Verster JE

Pandi-PerumalSR

RamaekersJG

de GlierJJ

Drugs, driving and traffic safety Basel, Switzerland Birkhii user Verlag 315 330

77. MaoY

ZhangJ

RobbinsG

ClarkeK

LamM

1997 Factors affecting the severity of motor vehicle traffic crashes involving young drivers in Ontario. Inj Prev 3 183 189

78. FannJR

LeonettiA

JaffeK

KatonWJ

CummingsP

2002 Psychiatric illness and subsequent traumatic brain injury: a case control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 72 615 620

79. CoxDJ

MikamiAY

CoxBS

ColemanMT

MahmoodA

2008 Effect of long-acting OROS methylphenidate on routine driving in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162 793 794

80. RedelmeierDA

VenkateshV

StanbrookMB

2008 Mandatory reporting by physicians of patients potentially unfit to drive. Open Med 2 E8 E17

81. WalkerJS

ColemanD

LeeJ

SquirePN

FriesenBJ

2008 Children's stigmatization of childhood depression and ADHD: magnitude and demographic variation in a national sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47 912 920

82. CareyB

2006 Nov 11 What's wrong with a child? Psychiatrists often disagree. The New York Times; Sect A:1

83. SciuttoMJ

EisenbergM

2007 Evaluating the evidence for and against the overdiagnosis of ADHD. J Atten Disord 11 106 113

84. VanderbiltT

2009 Traffic: why we drive the way we do. Toronto Random House Canada

85. WardNJ

WildeGJ

1996 Driver approach behaviour at an unprotected railway crossing before and after enhancement of lateral sight distances: an experimental investigation of a risk perception and behavioural compensation hypothesis. Saf Sci 22 63 75

86. EhrlingerJ

GilovichT

RossL

2005 Peering into the bias blind spot: people's assessments of bias in themselves and others. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31 680 692

Štítky

Interní lékařství

Článek Water Supply and HealthČlánek Sanitation and Health

Článek vyšel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Nejčtenější tento týden

2010 Číslo 11- Není statin jako statin aneb praktický přehled rozdílů jednotlivých molekul

- Magnosolv a jeho využití v neurologii

- Biomarker NT-proBNP má v praxi široké využití. Usnadněte si jeho vyšetření POCT analyzátorem Afias 1

- Ferinject: správně indikovat, správně podat, správně vykázat

- Optimální dávkování apixabanu v léčbě fibrilace síní

-

Všechny články tohoto čísla

- Why Do Evaluations of eHealth Programs Fail? An Alternative Set of Guiding Principles

- Strategies for Increasing Recruitment to Randomised Controlled Trials: Systematic Review

- Water Supply and Health

- Prescription Medicines and the Risk of Road Traffic Crashes: A French Registry-Based Study

- Air Pollution and the Microvasculature: A Cross-Sectional Assessment of In Vivo Retinal Images in the Population-Based Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)

- Can We Count on Global Health Estimates?

- Production and Analysis of Health Indicators: The Role of Academia

- WHO and Global Health Monitoring: The Way Forward

- Global Health Estimates: Stronger Collaboration Needed with Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- Sanitation and Health

- Combining Domestic and Foreign Investment to Expand Tuberculosis Control in China

- Colorectal Cancer Screening for Average-Risk North Americans: An Economic Evaluation

- Efficacy of Oseltamivir-Zanamivir Combination Compared to Each Monotherapy for Seasonal Influenza: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial

- Road Trauma in Teenage Male Youth with Childhood Disruptive Behavior Disorders: A Population Based Analysis

- A Call for Responsible Estimation of Global Health

- Hygiene, Sanitation, and Water: What Needs to Be Done?

- Defining Research to Improve Health Systems

- Which Path to Universal Health Coverage? Perspectives on the World Health Report 2010

- Doctors and Drug Companies: Still Cozy after All These Years

- Hygiene, Sanitation, and Water: Forgotten Foundations of Health

- The Imperfect World of Global Health Estimates

- PLOS Medicine

- Archiv čísel

- Aktuální číslo

- Informace o časopisu

Nejčtenější v tomto čísle- Efficacy of Oseltamivir-Zanamivir Combination Compared to Each Monotherapy for Seasonal Influenza: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial

- Doctors and Drug Companies: Still Cozy after All These Years

- Strategies for Increasing Recruitment to Randomised Controlled Trials: Systematic Review

- Prescription Medicines and the Risk of Road Traffic Crashes: A French Registry-Based Study

Kurzy

Zvyšte si kvalifikaci online z pohodlí domova

Autoři: prof. MUDr. Vladimír Palička, CSc., Dr.h.c., doc. MUDr. Václav Vyskočil, Ph.D., MUDr. Petr Kasalický, CSc., MUDr. Jan Rosa, Ing. Pavel Havlík, Ing. Jan Adam, Hana Hejnová, DiS., Jana Křenková

Autoři: MUDr. Irena Krčmová, CSc.

Autoři: MDDr. Eleonóra Ivančová, PhD., MHA

Všechny kurzyPřihlášení#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zapomenuté hesloZadejte e-mailovou adresu, se kterou jste vytvářel(a) účet, budou Vám na ni zaslány informace k nastavení nového hesla.

- Vzdělávání