-

Medical journals

- Career

Preoperative Radiotherapy of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Clinical Outcome of Short-Course and Long-Course Treatment with or without Concomitant Chemotherapy

Authors: I. Krajcovicova 1; E. Boljesikova 2; M. Sandorova 2; A. Zavodska 2; M. Zemanová 1; M. Chorvath 2; D. Ondrus 1

Authors‘ workplace: 1st Department of Oncology, Comenius University, Faculty of Medicine, St. Elisabeth Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 1; Department of Radiation Oncology, Slovak Medical University, St. Elisabeth Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 2

Published in: Klin Onkol 2012; 25(5): 364-369

Category: Original Articles

Overview

Background:

Preoperative radiotherapy is considered to be standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer. The timing and dosage of radiotherapy with or without preoperative chemotherapy remain controversial issues. The objective of this study was to evaluate relevant clinical outcomes of two preoperative radiotherapy regimens – the short-course and long-course radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer.Patients and Methods:

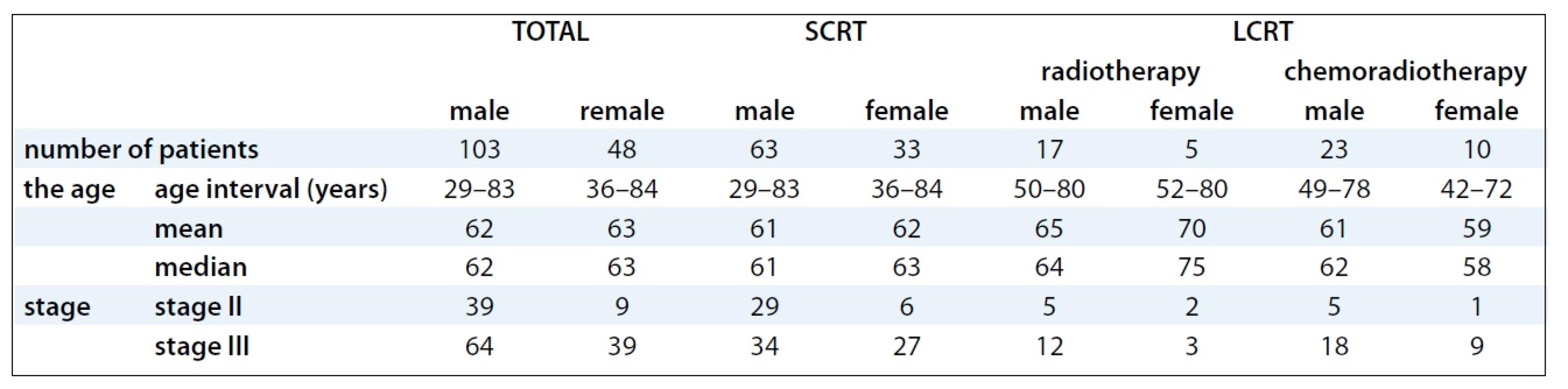

151 patients with stage II–III rectal cancer (103 males and 48 females) treated with preoperative radiotherapy between 01/1999 and 01/2008 were involved in this study. Analysed patterns included sphincter preservation, tumor downstaging, pathological complete remission, frequency of local recurrence, acute and late toxicity, perioperative complications, overall survival and disease-free survival.Results:

Tumor downstaging has been achieved by long-course radiotherapy alone (46%) or in combination with chemotherapy (5-FU or capecitabine, 61%). Pathological complete remission has also been achieved only in the group with long-course radiotherapy (13%). Long-course radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy significantly decreased post treatment local recurrence rates (5% versus 15% in the group after long-course radiotherapy alone, p = 0.0132). Statistically significant difference was confirmed in overall survival of patients treated with long-course radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy vs long-course radiotherapy alone (p = 0.015). Significant difference between the rate of perioperative complications, of acute and late toxicity, 3 and 5 years disease-free survival of treated patients after short-course radiotherapy and long-course radiotherapy was not confirmed.Conclusion:

Our findings provide convincing evidence that in comparison to preoperative short-course radiotherapy, the preoperative long-course radiotherapy in combination with chemotherapy is the most effective treatment modality for patients with operable locally advanced rectal cancer in terms downstaging and pathologic complete response. Increase in overall survival time as well as lower local recurrence rate makes this modality superior to other preoperative radiotherapy alternatives.Key words:

rectum – carcinoma – radiotherapyBackground

Due to its high rate of incidence and mortality, rectal cancer is currently one of the most serious problems in industrialized countries. In 2007, 675 malignant tumors of the rectum (C20) were diagnosed in males, which represented the standardised incidence rates (ASR-W) 19.3/100,000, and 392 in females, which represented ASR-W 8.0/100,000 [1] in the Slovak Republic (SR). During the last decade, treatment of rectal cancer underwent considerable development from surgical intervention to multimodal therapy [2,3], while surgery remains the most effective curative method [4]. First, adjuvant postoperative radiotherapy (RT) either alone or in a combination with chemotherapy has been introduced [5,6]. Second, a most effective and less toxic neoadjuvant treatment modality based either on a preoperative short--course (SCRT) [7,8] or on a preoperative long-course (LCRT) combined with chemotherapy has been shown to reduce the risk of persistence of the residual disease after surgery and to preserve sphincter damage [9,10]. Moreover, preoperative RT has further advantages in blood supply preservation, better tumor oxygenation, lower extent of small bowel irradiation, reduced risk of preoperative tumor spread and local recurrence (LR), in increasing tumor operability and prolonging survival time [2,11–13]. Although the advantage of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer has been well documented, the timing and dosage of preoperative RT need to be investigated further. The aim of this retrospective study was to bring deeper insight into the clinical outcome of preoperative SCRT vs LCRT with chemotherapy in the multimodal treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer.

Patients and Methods

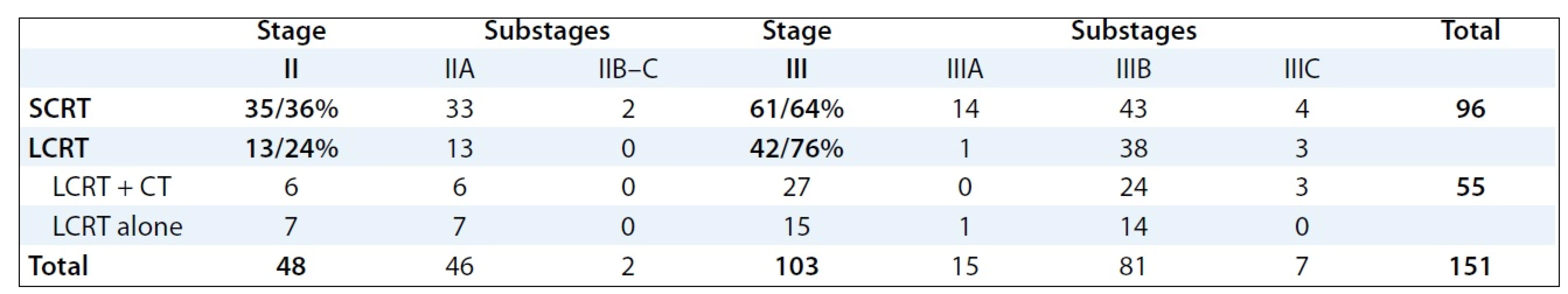

Between January 1999 and January 2008, 265 patients with rectal cancer were treated in our Institute using the multimodal preoperative RT with or without concomitant chemotherapy. For the retrospective study, 151 patients with locally advanced stage II and III of rectal cancer fulfilling the eligibility criteria (no distant metastases, previous preoperative radiotherapy or radical surgery) were selected. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients involved into the study are provided in Tab. 1. The mode of preoperative RT in relation to stages and substages of rectal cancer is illustrated in Tab. 2.

1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients.

2. Preoperative radiotherapy treatment according to stage of disease (no of patients).

LCRT + CT (chemotherapy) The histological features of rectal cancer involved tubular, mucinous-producing, papillary, villous and sigilocellular adenocarcinoma. Tumor staging and distance from anal verge were diagnosed before treatment by means of digital, rectoscopic and colonoscopic examination, by endorectal ultrasound, pelvic CT scan or MRI to evaluate local tumor extent and the involvement of mesorectal fascia (MRF), chest X-ray, CT scan of the chest and abdomen to diagnose the distant metastasis. Stage of tumors was established according to the TNM classification. The tumor was localized in the middle third of the rectum in 42 patients treated with SCRT vs 27 patients treated with LCRT, and in the lower third in 39 patients treated with SCRT vs 23 patients with LCRT. Evaluation of serum levels of CEA and CA19-9 tumor markers was performed before treatment; changes in levels related to treatment outcome were tested by regular check-ups after surgery.

All patients underwent planning CT in the treatment position (prone with a full bladder) on the belly board except for obese patients, patients with stoma or immobile patients who were in the supine position. The patients were irradiated on the linear accelerator, Clinac 2100 C/D, Varian, with high energy X-rays (18MV). The 3D conformal RT was employed in the treatment of all patients involved in the analysis. RT planning was accomplished using a 3-field technique (posterior beam, right-lateral beam, left-lateral beam) or 4-field technique (anterior – posterior beams, right-lateral beam, left-lateral beam). Target volumes were defined based on the known patterns of LR of rectal cancer. The Gross Tumor Volume (GTV) included all gross tumors seen on the planning CT scan. The Clinical Target Volume (CTV) included the primary tumor, the mesorectal tissue and regional lymph nodes (perirectal, presacral, internal iliac). The Planning Target Volume (PTV) was defined by CTV with edge of 1–2 cm. LCRT radiation treatment was applied by means of conventional fractionation (1.8–2.0 Gy per day to the total dose /TD/ of 45–46 Gy). Ninety-six pa-tients with rectal cancer were treated by preoperative SCRT (5 × 5.0 Gy per week, TD: 25 Gy), 55 were treated by preoperative LCRT (1.8–2.0 Gy per day to the TD: 45–46 Gy). Of these, 22 patients received LCRT alone, and 33 patients LCRT combined by concomitant chemotherapy (bolus 5-FU 350 mg/m2/day i.v. with LV × 5 days during the 1st and 5th weeks of RT or capecitabine 875 mg/m2 BID). Clinical outcomes of preoperative RT followed by surgery were analysed and evaluated in clinical stages II and III.

The average time of surgery after preoperative SCRT was 5 days (median 5.9 days, range 1–60 days); by preoperative LCRT, it was 42.6 days (median 42 days, range 17–72 days). All patients underwent radical surgery either with abdominoperineal resection or sphincter-preservation. Type of surgery after preoperative treatment was selected based on difference in tumor stage. Sphincter preservation was done in 47.3% after LCRT and in 47% after SCRT. Analysis showed no statistical difference between LCRT or SCRT and the type of operation in stages II and III (p = 0.9624) as well as between LCRT combined with chemotherapy and LCRT alone (p = 0.1858).

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS for Windows (the EView software and Excel 2010 with xlstat). The χ2 test was used to compare proportions, and the Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous variables. Survival in treatment arms was calculated by Kaplan--Meier estimates.

Results

Clinically relevant downstaging of rectal cancer was achieved in patients treated with preoperative LCRT alone or combined with chemotherapy. On contrary, tumor downstaging was not recorded in patients treated with preoperative SCRT. Downstaging rate by LCRT either alone (46%) or in a combination with chemotherapy (61%) showed no statistically significant difference (p = 0.2689).

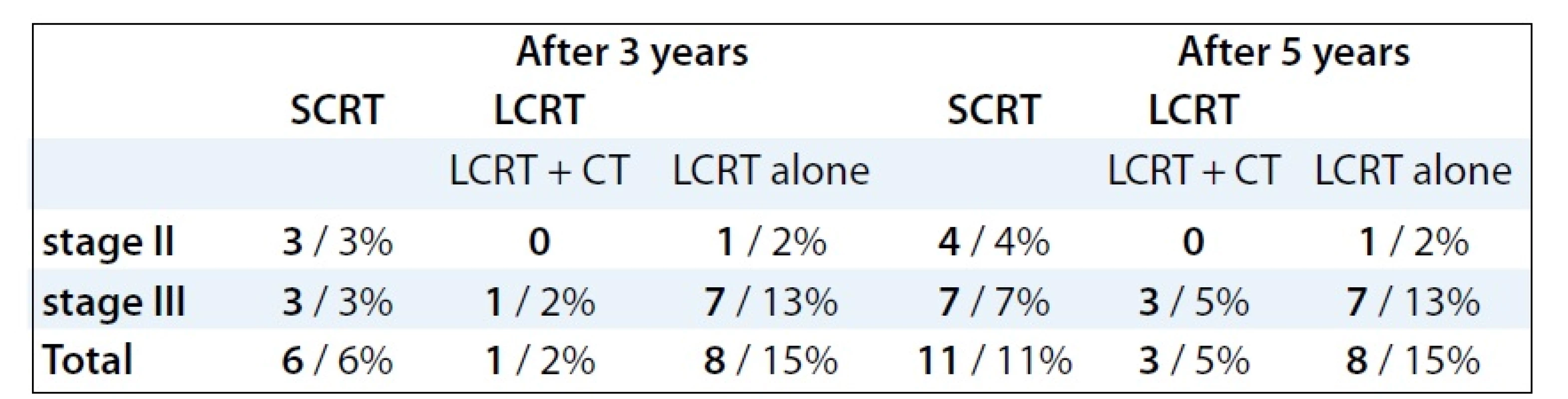

Pathological complete response (pCR) was achieved only in 7 patients (13%) receiving preoperative LCRT treatment. On the contrary, no pCR was observed in patients treated with SCRT. Three years after SCRT, LR reached 6% in both stages, after LCRT it was 16% (p = 0.04557, Tab. 3). The LR after treatment with LCRT and concomitant chemotherapy was observed in 2% cases, while after LCRT alone in 15% (p = 0.001062). Five years after treatment, the LR rate showed no significant difference between preoperative LCRT (20%) and SCRT (11%, p = 0.1522). However, statistically significant difference of LR frequency was demonstrated between LCRT with concomitant chemotherapy (6%) and LCRT alone (15%) (p = 0.0132). The occurence of LR was higher in clinical stage III 3 as well as 5 years after treatment (Tab. 3). Median time of LR was 23 months (range, 8–63 months) following surgery. Fig. 1 showed the time-related LR occurence after preoperative treatment for the whole group of patients. Fifty percent of LR appeared 22 months after surgery [11 for all 151 patients (7%)]. In 20 patients (13%), LR was diagnosed 5 years after surgery. During the entire time of analysis, LR occured in 22 patients (14%).

Fig. 1. Local recurrence time line after preoperative radiotherapy followed by surgery.

3. The incidence of local recurrence 3 and 5 years after preoperative treatment followed by surgery (no of patients/%).

Following preoperative LCRT, acute treatment toxicity was observed in 7 patients (13%), after SCRT in 5 patients (5%), mainly in the form of gastrointestinal disorders, dysuric symptoms and skin reactions. The difference between the two RT modalities was not statistically significant (p = 0.1002). Perioperative complications appeared in four patients after LCRT (7%), in 7 patients (7%) after SCRT without statistically significant difference (p = 0.9966). Late toxicity symptoms were reported in 16 patients (29%) after LCRT and 23 patients (24%) after SCRT without statistically significant difference (p = 0.4880). Along with psychosocial burden caused by the disclosure of cancer diagnosis, radical treatment and treatment side-effects [14,15]; emotional distress has been frequently observed in patients where the indication of preoperative RT was reason for the postponement of surgical intervention. This has been taken into account in the treatment planning undertaken in the patient’s presence [16].

Median follow-up for the whole group of 151 patients was 48 months (range, 2–128 months). Of the 96 patients treated with SCRT, 16 patients (17%) died due to cancer progression. Mean OS was 98 months (CI 95%: 89.29 to 105.7). The OS of 3 and 5 years after SCRT treatment reached 94% and 81%, respectively. Of the 55 patients treated with LCRT, 14 patients (26%) died due to cancer progression. The mean survival time was 71 months (CI 95%: 62.238 to 79.742). The OS of 3 years after treatment reached 83%, after 5 years 70%. No significant difference in 3 and 5 years OS between groups of patients treated either with LCRT or with SCRT (p = 0.101) was observed (Fig. 2). Four of 33 patients treated with LCRT with chemotherapy died due to tumor progression. Mean survival time in this group was 81 months (CI 95%: 71.527 to 90.407). The OS time of 3 years after treatment reached 93%, 5 years after treatment 84%. Ten patients of 22 treated with LCRT alone died due to the failure of treatment. Mean survival time was 48 months (CI 95%: 38.321 to 57.335), and 3 years OS was 67%, 5 years OS was 55% with clear statistically difference in OS preferring LCRT with chemotherapy over LCRT alone (p = 0.015) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Comparison of 5-year overall survival in patients treated with SCRT and LC RT.

Fig. 3. Comparison of 5-year overall survival in patients treated with LC RT alone and LC RT with chemotherapy.

The mean time of DFS was 51 months (range, 1–90 months) in the LCRT group of patients and 76 months (range, 1–128 months) in the SCRT group. In the LCRT group of patients, 3 - and 5-year DFS was 66% and 54%, respectively In the SCRT group of patients, 3 - and 5-year DFS was 73% and 66%, respectively There was no significant difference between these groups of patients regarding 3 - and 5-year DFS (p = 0.102) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Comparison of 5-year disease-free survival in patients treated with SCRT and LC RT.

Discussion

Randomized trials have demonstrated superior local control, lower toxicity and better compliance of RT or chemoradio-therapy administered before rather than after surgery [17,18]. According to results of the NSABBP R-03 study, significantly more patients treated with preoperative RT survived 5-year disease-free as compared with patients treated with postoperative RT (65% vs 53%). Likewise, the number of patients reaching the 5-year OS was increased by means of LCRT from 53 % to 66%, and the LR was dropped to 10% [19]. The German CAO/ARO/AIO 94 trial confirmed that in contrary to postoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer, preoperative chemoradio-therapy produces significantly lower LR rates, less acute and chronic toxicity and an increased rate of sphincter preservation [20,21]. The preoperative RT with or without chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced rectal cancer has been used for the past two decades [22]. The preoperative SCRT or LCRT combined with chemotherapy are two different options with proven efficacy. The first approach may be reasonable in cases, where complete surgical removal of the tumor is indicated. Preoperative combined chemoradiotherapy is more appropriate for patients who need significant downsizing of the tumor is needed before tumor resection with clear surgical margins [23]. Preoperative RT combined with chemotherapy increases pathologic downstaging when compared to radiation alone. Theoretical advantages of the preoperative strategy include increased radiosensitivity due to more oxygenated cells and decrease of tumor seeding during surgery [25]. Acute toxicity is more pronounced during combined preoperative treatment, but long-term side-effects may be more prevalent by using SCRT. So far, the increase in local control following neoadjuvant treatment could not be translated into substantial survival benefit [26].

In our analysis, there were more patients with higher stage of disease treated with LCRT than with SCRT (p = 0.000002), and so the results need to be considered in this context. The high-rate stage II tumors in the SCRT group may imply that this group included more favourable cases. The number of patients with low tumors location from anal verge is comparable between two groups of patients and stage of disease (p = 0.88595). The irradiation technique was identical in the two groups and was based on relevant guidelines.

Our analysis demonstrated that tumor shrinkage after preoperative LCRT has not resulted in a higher rate of anterior resection. The sphincter preservation rate was comparable with results of the Uppsala trial (43.5%) [24]. In comparison to our results, slightly higher rates of sphincter preservation after preoperative RT (67 % and 69 %, respectively), was demonstrated in recent Dutch and German randomised trials [20,25,26].

In the present study, the downstaging effect was achieved only in patients treated with LCRT alone (61%) or combined with chemotherapy (64%, p > 0.05). Pathological CR was achieved in 7 patients (13%) treated with preoperative LCRT, while preoperative SCRT remained without effect. Our results are comparable with the results of large randomized studies [27,28]. The LR rate in patients treated with LCRT with or without concomitant chemotherapy showed time-related increase: three years after treatment, the LR values were rather low. However, 5 years after treatment, statistically significant difference of LR between subgroups of patients treated with LCRT alone or LCRT with chemotherapy preferred the later modality. The results demonstrated a significant benefit in local control of RT combined with chemotherapy. The incidence of LR was higher in stage III of disease 3 as well as 5 years after treatment, and the crude rate of LR was 14% in the whole group of our 151 patients.

The LR rate in our analysis is higher than in randomized studies in which the total mesorectal excision technique has been used (13% – Uppsala trial, 6% – German trial) [20,24]. One reason of the difference might be attributed to the suboptimal quality of the used surgical technique. In our analysis, acute toxicity rates of preoperative LCRT were lower than in large trials (German Rectal Cancer Study – 27%) [21], while in the present study, slightly higher late toxicity rate was observed. Statistical analysis did not confirm significant difference in 3 - and 5-year OS between patients treated by SCRT or LCRT (94% and 81%, 83% and 70%, respectively). However, clear significant difference in OS of patients treated with LCRT alone or with LCRT with concomitant chemotherapy was demonstrated (67% and 55%, 93% and 84%, respectively). Our results of the 5-year OS after preoperative LCRT in combination with chemotherapy or SCRT are slightly higher compared with the results of Uppsala trial (58%), Dutch trial (63.5%) and German Cancer Study Group (76%) [20,25,26]. Three and 5 years OS and DFS did not show any statistically significant difference between stage II and III of disease in the whole group of our patients.

Conclusion

Our results presented above clearly demonstrated that in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer, the preoperative LCRT combined with chemotherapy is superior to other RT modalities, leading to increased tumor shrinkage, operability, sphincter preservation rate, OS and DFS of treated patients. This modality significantly reduced LR of rectal cancer and improved overall quality of life of surviving patients.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, pruducts, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Krajcovicova Ivana, MD

1st Department of Oncology

Comenius University, Faculty of Medicine

St. Elisabeth Cancer Institute

Heydukova 10

812 50 Bratislava

Slovak Republic

e-mail: ikrajcov1@hotmail.com

Submitted: 11. 6. 2012

Accepted: 7. 7. 2012

Sources

References

1. Safaei-Diba C, Pleško I, Hlava P. Cancer Incidence in the Slovak Republic 2007. Bratislava: National Health Information Center 2012.

2. Glimelius B, Påhlman L, Cervantes A et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010; 21 (Suppl 5): v82–v86.

3. Glimelius B. Introduction to optimal management of rectal cancer. EJC Supplements 2005; 65 : 345–347.

4. Påhlman L, Bohe M, Cedermark B et al. The Swedish rectal cancer registry. Br J Surg 2007; 94(10): 1285–1292.

5. Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group. Adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic overview of 8,507 patients from 22 randomised trials. Lancet 2001; 358(9290): 1291–1304.

6. Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Williamson SK et al. Phase III trial of fluorouracil-based chemotherapy regimens plus radiotherapy in postoperative adjuvant rectal cancer: GI INT 0144. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(22): 3542–3547.

7. Gerard JP, Chapet O, Nemoz C et al. Improved sphincter preservation in low rectal cancer with high-dose preoperative radiotherapy: the lyon R96-02 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22(12): 2404–2409.

8. Peeters KC, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID et al. Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 2007; 246(5): 693–701.

9. Engstrom PF. NCCN Colon and Rectal Cancer Guidelines [online]. Update 11 March 2010. Available from: http://cme.medscape.com/viewarticle/720232.

10. Collette L, Bosset JF, den Dulk M et al. Patients with curative resection of cT3-4 rectal cancer after preoperative radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy: does anybody benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy? A trial of the EORT Cancer Radiation Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(28): 4379–4386.

11. Valentini V, Coco C, Cellini N et al. Ten years of preoperative chemoradiation for extraperitoneal T3 rectal cancer: acute toxicity, tumor response, and sphincter preservation in three consecutive studies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 51(2): 371–383.

12. Valentini V, Morganti AG, Gambacorta MA et al. Preoperative hyperfractionated chemoradiation for locally recurrent rectal cancer in patients previously irradiated to the pelvis: a multicentric phase II study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 64(4): 1129–1139.

13. Eriksen MT, Wibe A, Haffner J et al. Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group. Prognostic groups in 1,676 patients with T3 rectal cancer treated without preoperative radiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50(2): 156–167.

14. Bencova V, Svec J, Bella V. The role of psychosocial oncology in the health care of breast cancer survivors. Bratisl Lek Listy 2009; 110(6): 374.

15. Bencova V, Mrazova A, Svec J. Psychosocial morbidity – an unfilled gap in undergraduate courses of medicine and nursing. Clin Social Work 2010; 1–2 : 37–46.

16. Bencova V, Bella J, Svec J. Dynamika vývoja psychosociálnej záťaže prežívajúcich pacientok s karcinómom prsníka: klinický úspech s psychosociálnymi dôsledkami. Klin Onkol 2011; 24(3): 203–208.

17. Gunderson LL, Sargent DJ, Tepper JE et al. Impact of T and N stage and treatment on survival and relapse in adjuvant rectal cancer: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22(10): 1785–1796.

18. Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing preoperative short-course radiotherapy with preoperative conventionally fractionated chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2006; 93(10): 1215–1223.

19. Roh MS, Colangelo LH, O’Connell MJ et al. Preoperative multimodality therapy improves disease-free survival in patients with carcinoma of the rectum: NSABBP R-03. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(31): 5124–5130.

20. Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W et al. German Rectal Cancer Study Group. Preoperative vs postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351(17): 1731–1740.

21. Arbea L, Ramos LI, Martínez-Monge R et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) vs. 3D conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT) in locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC): dosimetric comparison and clinical implications. Radiat Oncol 2010; 5 : 17.

22. Ferrigno R, Novaes PE, Silva ML et al. Neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy in the treatment of fixed and semi-fixed rectal tumors. Analysis of results and prognostic factors. Radiat Oncol 2006; 1 : 5.

23. Hoffmann W, Lordick F, Becker-Schiebe M. (Neo-)Adjuvant radiochemotherapy in stage II/III rectal cancer. MEMO 2011; 4(2): 90–93.

24. Påhlman L, Glimelius B. Pre - or postoperative radiotherapy in rectal and rectosigmoid carcinoma. Report from a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg 1990; 211(2): 187–195.

25. Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(9): 638–646.

26. Marijnen CA, Peeters KC, Putter H et al. Cooperative investigators of the TME trial. Long term results, toxicity and quality of life in the TME trial. Presented at ESTRO Meeting. Amsterdam 2004, October 24–28. Abstract 283.

27. François Y, Nemoz CJ, Baulieux J et al. Influence of the interval between preoperative radiation therapy and surgery on downstaging and on the rate of sphincter-sparing surgery for rectal cancer: the Lyon R90-01 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17(8): 2396–2402.

28. Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Klein Kranenbarg E et al. No downstaging after short-term preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19(7): 1976–1984.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2012 Issue 5-

All articles in this issue

- Analysis of Prognostic Factors in Osteosarcoma Adult Patients, a Single Institution Experience

- Neoplastic Effect of Indomethacin in N-methyl-N-nitrosourea Induced Mammary Carcinogenesis in Female Rats

- Importance of Expression of DNA Repair Proteins in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer

- Bloodstream Infections of the Intravascular Access Devices – Case Reports and Review of the Literature

- Another Positive Study of Ovarian Carcinoma

- BRAF Mutation: a Novel Approach in Targeted Melanoma Therapy

- The Substance of Genetic Information – Nucleic Acids

- Dabrafenib: the New Inhibitor of Hyperactive B-RAF Kinase

- Uterine Sarcomas – a Review

- Preoperative Radiotherapy of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Clinical Outcome of Short-Course and Long-Course Treatment with or without Concomitant Chemotherapy

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Analysis of Prognostic Factors in Osteosarcoma Adult Patients, a Single Institution Experience

- Uterine Sarcomas – a Review

- Bloodstream Infections of the Intravascular Access Devices – Case Reports and Review of the Literature

- BRAF Mutation: a Novel Approach in Targeted Melanoma Therapy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career