-

Medical journals

- Career

COMPLICATIONS OF LOWER EXTREMITY HEMATOMAS IN PATIENTS WITH PRE-INJURY WARFARINE USE

Authors: P. Bukovčan; J. Koller

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Burns and Reconstructive Surgery, Comenius University and University Hospital Bratislava, Slovak Republic

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 59, 2, 2017, pp. 56-59

INTRODUCTION

Warfarin is the most common oral anticoagulant used for chronic anticoagulation therapy, which is an integral part of the treatment in patients with various diagnoses in indicated cases1,2 . Despite beneficial treatment effect, those patients can be vulnerable to possible post-traumatic complications, which may occur. Although complications of pre-injury Warfarin use have already been reported3,4,5,6, lower extremity hematomas in patients with pre-injury Warfarin use are seldom mentioned in the literature. As a result of even minor lower-extremity skin injury, closed and open haematomas can occur, that can cause complications such as infection and full-thickness skin loss subsequently requiring surgical management. Our department has encountered patients with such complications. The aim of this study is to identify these patients, to analyse data, used treatment methods and outcome of these patients and to identify the risk factors for this type of complication.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective review of our registry data, identifying all the patients with pre-injury Warfarin use admitted with a hematoma or full-thickness skin loss in the ten-year period from January 2006 to December 2015. Demographic data, wound surface area, methods of wound closure, length of hospital stay in our department, length of previous hospital stay in other departments were obtained. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). A value of p < 0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance. The data obtained were compared with the results and findings of similar studies and were discussed. (Figures 1–5.)

1. 72-year-old warfarinised female patient (atrial fibrillation) with defect of the left lower leg caused by infected haematoma created after an injury. Patient was transferred from another hospital 21 days post injury after incision and evacuation of the hematoma.

2. Same patient after surgical debridement of the wound. Note the deep undermining of the wound

3. Same patient after surgical debridement of the wound. Note the deep undermining of the wound

4. Wound appearance after 5 days of NPWT immediately before wound closure procedure. The undermined space is almost obliterated, wound surface covered by healthy granulation tissue

5. Healed wound 12 days after wound closure by splitthickness skin autograft. Softened skin margins with no oedema enabled partial suture proximally

RESULTS

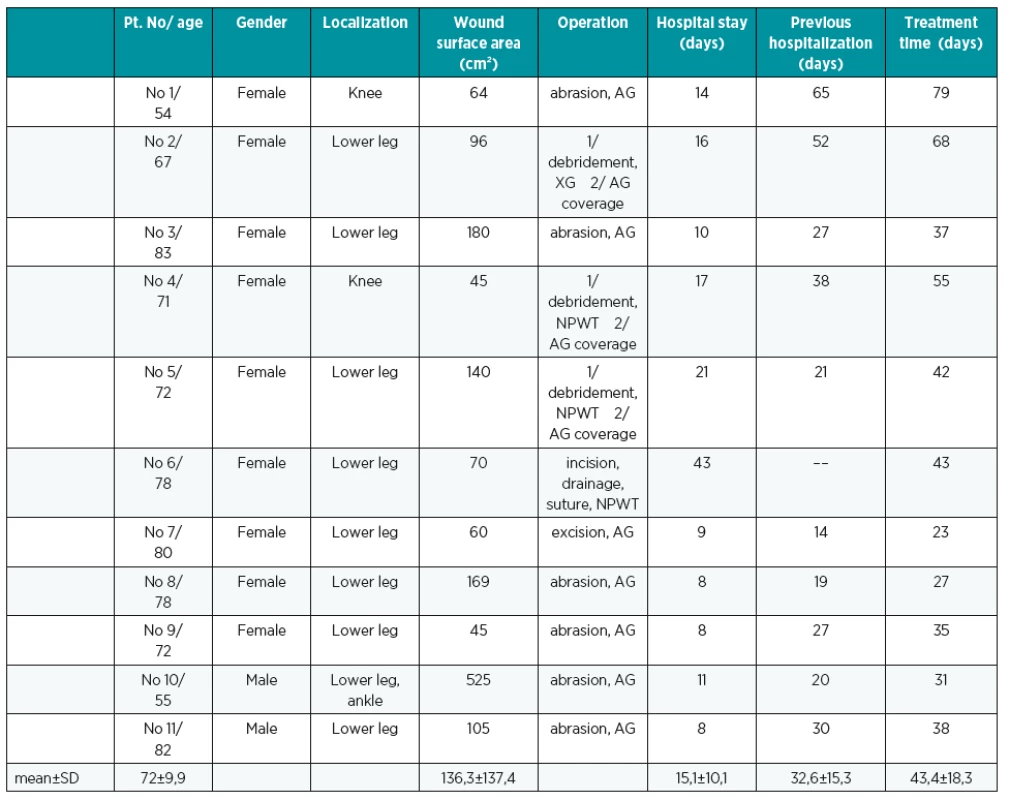

Overall 11 patients, 9 women (82%) and 2 men (18%) with mean age of 72 ± 9.98 years (range 54–83) were identified in this retrospective review. In 7 patients, Warfarin was used in the management of chronic atrial fibrillation and in 4 patients for deep vein thrombosis. All injuries occurred in a domestic setting. Except of one female patient primarily admitted to our department with closed hematoma of the lower leg 14 days post-injury, all patients were hospitalized primarily in local/regional hospitals for an average period of 32.6 days where, after bridging anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin, evacuation of the hematomas, debridement and, in three patients, also negative-pressure wound therapy had been performed. Subsequently, patients with defects requiring surgical wound closure were transferred to our department. All defects were localised on the lower extremity, including knee in two and ankle in one case. Measured on the day of admission to our department in each patient, the average wound surface area was 136.3 cm² (range 45–525 cm²). The wound surface was covered by slough in four patients, in one patient it was partially necrotic, in one patient the wound edges were deeply undermined. In the rest of the patients the wound surfaces were covered by clean granulation tissue. All 11 patients required surgical wound closure. In 10 patients the wound closure was obtained by split-thickness skin autograft. Due to inadequate wound condition for primary closure, three of them required two stage operation including negative pressure wound therapy in two and skin xenograft coverage in one patient respectively, for the coverage of debrided wounds in the first stage operation. Skin xenograft as a temporary biological skin substitute and negative pressure wound therapy in those patients had been used because the take of the skin graft was questionable. In the second stage operation skin xenograft or sponge had been removed and replaced by skin autografts. In one female patient admitted for closed hematoma of the lower leg 14 days after injury, incision, evacuation of the hematoma, insertion of the Redon drain and suture of the incision had been performed. The outflow end of Redon drain was inserted into the foam dressing placed over the sutured wound, sealed by occlusive film dressing and attached to the negative-pressure unit, thus supporting simultaneously the drainage and healing of the wound. The length of hospital stay in our department averaged 15.1±10.1 days (range 8–43). At the end of hospitalization in our department, all the wounds were healed. In ten patients hospitalized previously in other facilities, the difference between the length of hospital stay in our department and the length of previous hospitalizations is statistically significant (paired t test, p=0.003). When adding the length of hospital stays in other facilities with the length of hospital stays in our department, the average treatment time was 45.9±16.5 days. The data and results obtained are shown in the Table 1.

1. Patients and results

Abbreviations: AG – split thickness skin autograft, NPWT – negative pressure wound therapy, XG – skin xenograft, SD – standard deviation DISCUSSION

Patients treated with warfarin are mainly in older age group, which corresponds fully with the mean age of the patients included in the study (72±9.98). They are represented also by skin vulnerability as ageing reduces skin elasticity, dermal anchorage and subcutaneous tissue. Except Warfarin use and the need of proper adjustment of dosage in therapeutic range, older people also have a higher risk of other factors predisposing to lower limb haematomas including falls, diabetes-related neuropathy, lower leg vascular disease. The predominance of women in our study can be explained by their greater activity in household tasks performance thus creating a greater chance to sustain an injury.

According to our point of view, lower extremity hematomas in our patients developed from a shearing injury, causing separation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from muscle fascia. This created a space capable of filling with blood, causing high-pressure forces on the tissues potentially causing skin necrosis with development of a very complex chronic wound that is difficult to manage, particularly in the elderly patient with multiple concomitant comorbidities. According to the literature7, the cases of 3 patients with intramuscular bleeding, who developed compartment syndrome after sustaining very low-energy trauma while anticoagulated with warfarin were described.

Treatment of full-thickness lower extremity hematomas in anticoagulated patients with Warfarin was previously described in four elderly patients (77.2 ± 12.7 years) presented with full-thickness, necrotic, lower extremity wounds8. Wound dimensions averaged 19.1 cm ± 8.9 cm in length, 12.2 cm ± 9.5 cm in width. After initial debridement under local anesthesia, the patients were treated on the outpatient basis while maintaining therapeutic anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. Following primary short treatment with wet-to-moist saline dressing changes, continuous negative pressure therapy was for an average of 23.8 ± 3.2 days. All wounds were then treated with application of a living bilayered skin substitute ([LSS], Apligraf®, Organogenesis, Canton, MA) meshed 1.5 : 1 in an outpatient setting. Additional LSS application was performed if, after 6 weeks following LSS application, further epithelialization and closure of the wounds stalled. Authors decribe their near total outpatient treatment protocol as minimally disruptive to the patients’ routines, while maintaining anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, although in two patients the cessation of anticoagulation therapy before inpatient operative debridement was described. All wounds completely epithelialized within an average of 39.0 ± 21.9 weeks from the initiation of therapy. Eventhough our patients were not managed on an outpatient basis but hospitalized and treated surgically, this is in contrast to our patient´s outcome with the average treatment time (including also hospitalization time in other facilities prior to the admission to our department) of 43.4±18.3 days. In comparison with near total outpatient treatment protocol described by the authors of compared study, with regards to the results achieved, we believe that our patients have benefited from shorter treatment time substantially reduced by surgical wound closure methods. Pertaining surgical treatment, there were no complications observed. To minimize the risk of complications, two-stage operative approach described in results was used in three patients with wound conditions unsuitable for definitive wound closure after the debridement. Our experience with negative pressure wound therapy, used in three of our patients, is in accordance with scientific evidence of its beneficial treatment effect by stimulation of blood flow, angiogenesis and granulation formation, derivation of soluble wound healing inhibitor substances from the wound area, mechanical forces pulling the wound edges together, reduction of tissue oedema and reduction of bacterial contamination9.

Preinjury warfarin use has been demonstrated to be an independent predictor of mortality in major trauma patients3, although the proper dosage of Warfarin is equally important6.

As the indications for oral anticoagulation therapy have been broadened, increasing number of warfarinized patients may represent a risk of bleeding complications with possible hematoma occurence in a larger number of patients.

CONCLUSION

As it is shown in the manuscript, the consequences of even minor lower extremity trauma in patients with pre-injury Warfarin use can be serious, with development of a very complex chronic wound that is difficult to manage, particularly in the elderly patient with multiple concomitant comorbidities. Therefore, clinicians, first contact physicians, and also patients alone need to be aware of vulnerability of this group of patients. According to our point of view, also the proper dosage of anticoagulant medication and the willingness of the patients to take part in the outpatient appointments to adjust the dosis of medication and keep it in therapeutic range is of paramount importance.

Corresponding author:

Peter Bukovčan, M.D., Ph.D.

Department of Burns and Reconstructive Surgery

University Hospital Bratislava

Ružinov Hospital

Ružinovská 6, 826 06 Bratislava

Slovak Republic

E mail: bukovcanmed@hotmail.com

Sources

1. Smith P, Arnesen H, Holme I. The effect of warfarin on mortality and reinfarction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jul 19;323(3):147-52.

2. Ridker PM et al. Long-term, low-intensity warfarin therapy for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 10;348(15):1425-34.

3. Lecky FE et al. The effect of preinjury warfarin use on mortality rates in trauma patients: a European multicentre study. Emerg Med J. 2015 Dec;32(12):916-20.

4. Ivascu FA, Janczyk RJ, Junn FS, Bair HA, Bendick PJ, Howells GA. Treatment of trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage on preinjury warfarin. J Trauma. 2006 Aug;61(2):318-21.

5. Miller J et al. Delayed intracranial hemorrhage in the anticoagulated patient: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Aug;79(2):310-3.

6. Pieracci FM, Eachempati SR, Shou J, Hydo LJ, Barie PS. Degree of anticoagulation, but not warfarin use itself, predicts adverse outcomes after traumatic brain injury in elderly trauma patients. J Trauma. 2007 Sep;63(3):525-30.

7. Gaines RJ, Randall CJ, Browne KL, Carr DR, Enad JG. Delayed presentation of compartment syndrome of the proximal lower extremity after low-energy trauma in patients taking warfarin. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2008 Dec;37(12):E201-4.

8. La Rosa CA, Fanelli C. Successful Outpatient Treatment of Full-thickness, Necrotic, Lower - extremity Ulcers Caused by Traumatic Hematomas in Anticoagulated Patients. Wounds. 2011 Oct;23(10):293-300.

9. Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):553-62.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2017 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Editorial

- COMPLICATIONS OF LOWER EXTREMITY HEMATOMAS IN PATIENTS WITH PRE-INJURY WARFARINE USE

- SURGICAL CORRECTION OF LABIA MINORA HYPERTROPHY, A PERSONAL TECHNIQUE

- SUTURE VERSUS FIBRIN GLUE MICRONEURAL ANASTOMOSIS OF THE FEMORAL NERVE IN SPRAGUE DEWLY RAT MODEL. A COMPARATIVE EXPERIMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF THE CLINICAL, HISTOLOGICAL AND STATISTICAL FEATURES

- INTRAOPERATIVE FAT GRAFTING INTO THE PECTORALIS AND LATISSIMUS DORSI MUSCLES-NOVEL MODIFICATION OF AUTOLOGOUS BREAST RECONSTRUCTION WITH EXTENDED LATISSIMUS DORSI FLAP

- HAS A GLOMUS TUMOR ALWAYS A QUICK DIAGNOSIS?

- CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIPHERAL NERVE INJURY REPAIR

- SUBACUTE ARTERIAL BLEEDING AFTER SIMULTANEOUS MASTOPEXY AND BREAST AUGMENTATION WITH IMPLANTS: CASE REPORT

- AUTOLOGOUS FAT TRANSFER, BREAST LIPOMODELLING AND FAT TRANSFER TO THE FACE: CURRENT GOLD STANDARDS AND EMERGING NEW DATA

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- SURGICAL CORRECTION OF LABIA MINORA HYPERTROPHY, A PERSONAL TECHNIQUE

- INTRAOPERATIVE FAT GRAFTING INTO THE PECTORALIS AND LATISSIMUS DORSI MUSCLES-NOVEL MODIFICATION OF AUTOLOGOUS BREAST RECONSTRUCTION WITH EXTENDED LATISSIMUS DORSI FLAP

- COMPLICATIONS OF LOWER EXTREMITY HEMATOMAS IN PATIENTS WITH PRE-INJURY WARFARINE USE

- HAS A GLOMUS TUMOR ALWAYS A QUICK DIAGNOSIS?

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career