-

Medical journals

- Career

Odontoid fracture in the elderly, our therapeutic approach

Authors: Milan Krtička; Martin Petráš; Martin Chovanec; Pavel Smékal; Andrej Bilik

Authors‘ workplace: Klinika úrazové chirurgie FN Brno

Published in: Úraz chir. 27., 2020, č.1

Overview

Objective: Retrospective evaluation of the results of conservative and surgical treatment in senior population patients with type 2 and 3 odontoid fracture according to Anderson DʼAlonzo (A-A) classification treated at the Trauma Clinic of the University Hospital in Brno from 2013 to 2017.

Material and methods: The monitored set consisted of 52 patients (28 women, 24 men) aged over 65, the average age being 82 years (66 – 93 years) and the median being 76 years. Fractures of the dens were evaluated according to Anderson and DʼAlonzo classification. Conservative therapy using the Philadelphia-type hard collar for 12 weeks was indicated in patients with non-dislocated or minimally dislocated type II and type III odontoid fracture.

Surgical treatment using 2 compression screws C1-2 posterior fusion was primarily indicated in dislocated fractures. The patient monitoring length was minimally 6 months from the injury. X-ray check-ups including clinical check-up of the monitored patients were performed on day 4 - 7 from the diagnosed odontoid fracture or after the surgery performed and also in week 4, 8, 12 and 24 after the injury, when functional x-rays of cervical spine were also made.

Results: According to x-ray images, healing of the fracture was observed after 6 months of treatment in 47 % of the patients with type II odontoid fracture. Fracture line persisted in 53 % of patients, but the treatment was conservative without clinical correlate and with regard to comorbidities, meaning recommended use of a soft collar for verticalization. In type III odontoid fractures, healing of the fractures was observed in 71 % of the patients. Besides non-healing of the fracture, we evaluated the other therapeutic complications as well. The least complications occurred in conservatively treated patients with a hard collar, where we particularly observed collar galls. Most complications were represented in patients treated by Halo fixation, where we observed numerous complications such as pin track infection, swallowing disorders, pneumonia, and in 53 % of patients recurring loss of odontoid fracture reposition with subsequent non-healing of the fracture.

Conclusion: Odontoid fractures belong to the most frequent cervical spine injuries in the elderly population; the incidence has been increasing and there is no uniform treatment concept which, however, should be individual, also with regard to the associated comorbidities. And with regard to the aforementioned it is important to realize that even a stable ligament false joint is tolerated very well by the elderly people and where neurological symptomatology is absent, it is not always necessary to aim for bone healing of the fracture.

Keywords:

senior – therapy – fracture – Dens axis

INTRODUCTION

Upper cervical spine fractures represent a frequent injury in elderly people, representing more than 50 % of all spine injuries in this age group [11]. In patients aged 75 and more, odontoid fractures represent the most frequent cervical spine injury at all [4, 14]. The growing risk of odontoid injury relates to development of osteoporosis and also to the occurrence of degenerative spine modifications. These are manifested particularly in the area of cervical vertebrae 4 to 7, which represent the most mobile spine segment; the affected mobile segments grow rigid in consequence of degeneration and thus it is the C1-2 region [10] that becomes the most mobile segment of the cervical spine in elderly people. This is why spine injuries at young age are mostly caused by high-energy injury and the lower cervical spine is mostly affected; in the elderly people, on the opposite, the most cases represent a low-energy injury (typically the fall down from the body height on the face) with the injury localised in the upper cervical spine region [17]. Therapy of unstable fractures in the region of upper cervical spine in elderly people continues to be controversial and there is not uniform and established therapeutic guideline [8]. Reasons for controversy include: significant comorbidities of elderly people, severity of surgical procedures and reduced bone healing potential, which result in higher morbidity and mortality of the surgical treatment. The aim of our statement is to evaluate the results of conservative and operating treatment in elderly patient population with odontoid fractures who were treated at our site during the five-year period.

MATERIAL AND METHODOLOGY

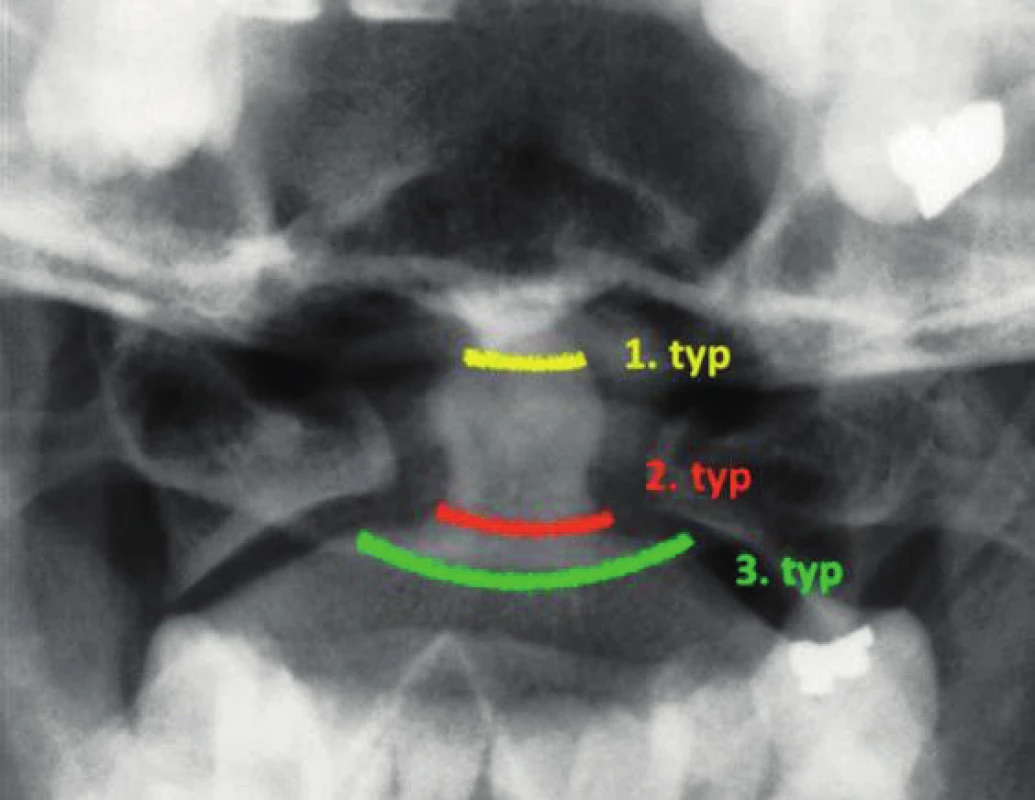

Retrospective study enrolled 74 patients with type II and III odontoid fracture according to Anderson D‘Alonzo (A-A) classification treated at the Trauma Clinic of the University Hospital in Brno from 2013 to 2017. The hospital information system including the x-ray documentation browser was used for retrospective evaluation of the set of patients. The following inclusion criteria were determined in the observed set of patients: age 65 and more, type II and III fracture according to A-A classification (Fig. 1), duration of the monitoring at least 6 months from the injury. Exclusive criteria included associated injuries of other spine section, presence of other skeletal injuries requiring surgical treatment, combination of 2 invasive methods of an odontoid fracture (Halo brace + direct osteosynthesis or Halo brace + posterior C1-2 fusion).

1. X-ray transoral projection of the upper cervical spine. Odontoid fracture types according to Anderson D’Alonzo classification are marked in colour. Yellow colour shows type I fractures in the region of odontoid apex, the red colour shows type II in the region of odontoid base, and green colour shows type III of the fracture extending from the base to the C2 vertebrae body

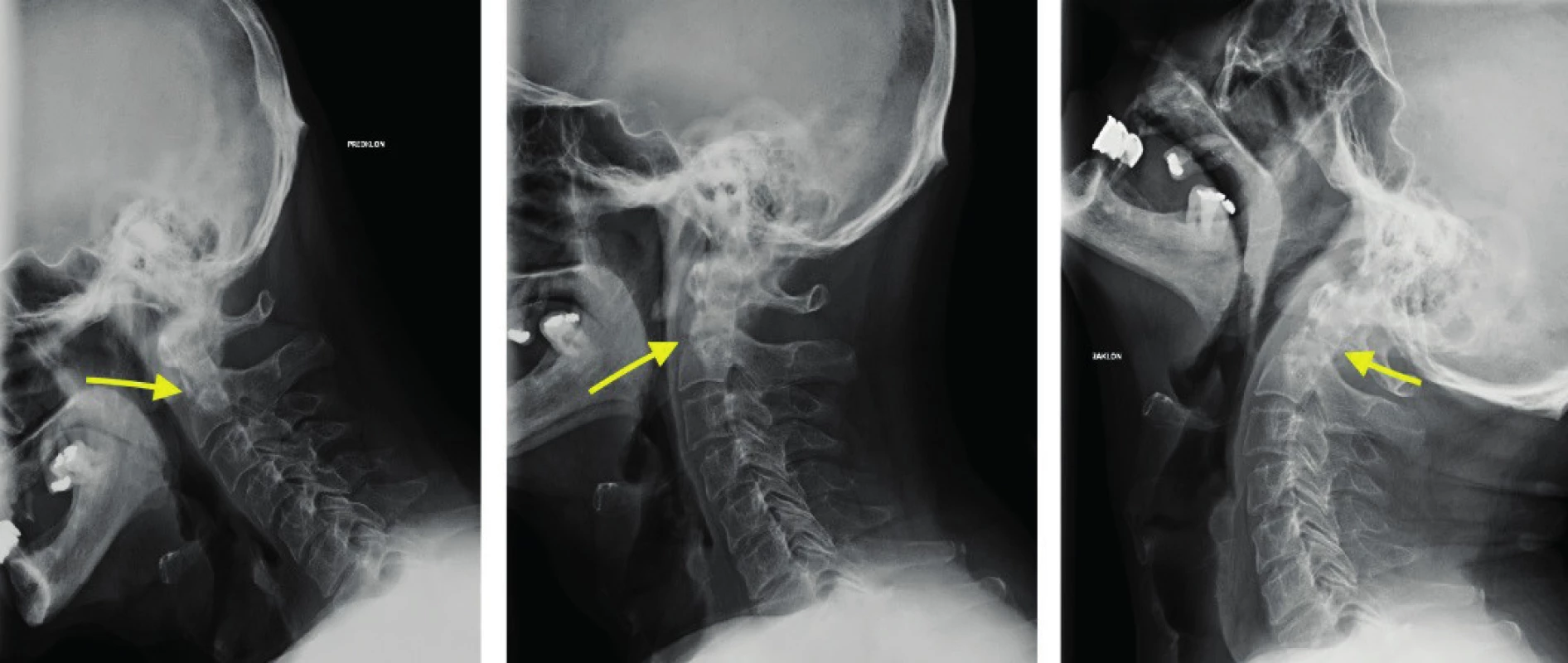

Diagnostic algorithm in all patients included the entrance x-ray examination of the cervical spine in anteroposterior and lateral projection supplemented with transoral projection. Where fracture in the dens axis region were diagnosed, the x-ray examination was always accompanied by spine CT scan. Odontoid fractures were evaluated according to Anderson and DʼAlonzo classification [1]. As a default, x-ray images were acquired from all patients on days 4 - 7 after the diagnosed odontoid fracture or after the operating procedure; in the next scheme, x-ray images were acquired in the interval of 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks from the injury, when functional images of cervical spine were acquired as well, see Fig. 2. The same image was taken if a patient returned for a follow-up visit after one year from this follow-up visit. The criterion for definition of a healed odontoid fracture was a ceased fracture line in the area of dens axis and the absence of its pathological dislocation on the acquired functional images, see Fig. 1. CT examination was not performed as a routine in term of the treatment of the patients. Only when complications occur (secondary dislocation of dens, migration of osteosynthetic material, complete failure of performed osteosynthesis).

2. Functional x-ray images of cervical spine acquired 6 months after the odontoid fracture. The arrow shows a still present fracture line in the C2 vertebrae area. However, pathological shift of axis of the affected spinal section is not obvious in the forward and backward bend

Conservative therapy in a form of application of the Philadelphia hard collar for 12 weeks from the injury was primarily indicated in patients with non-dislocated or minimally dislocated type II and type III odontoid fracture.

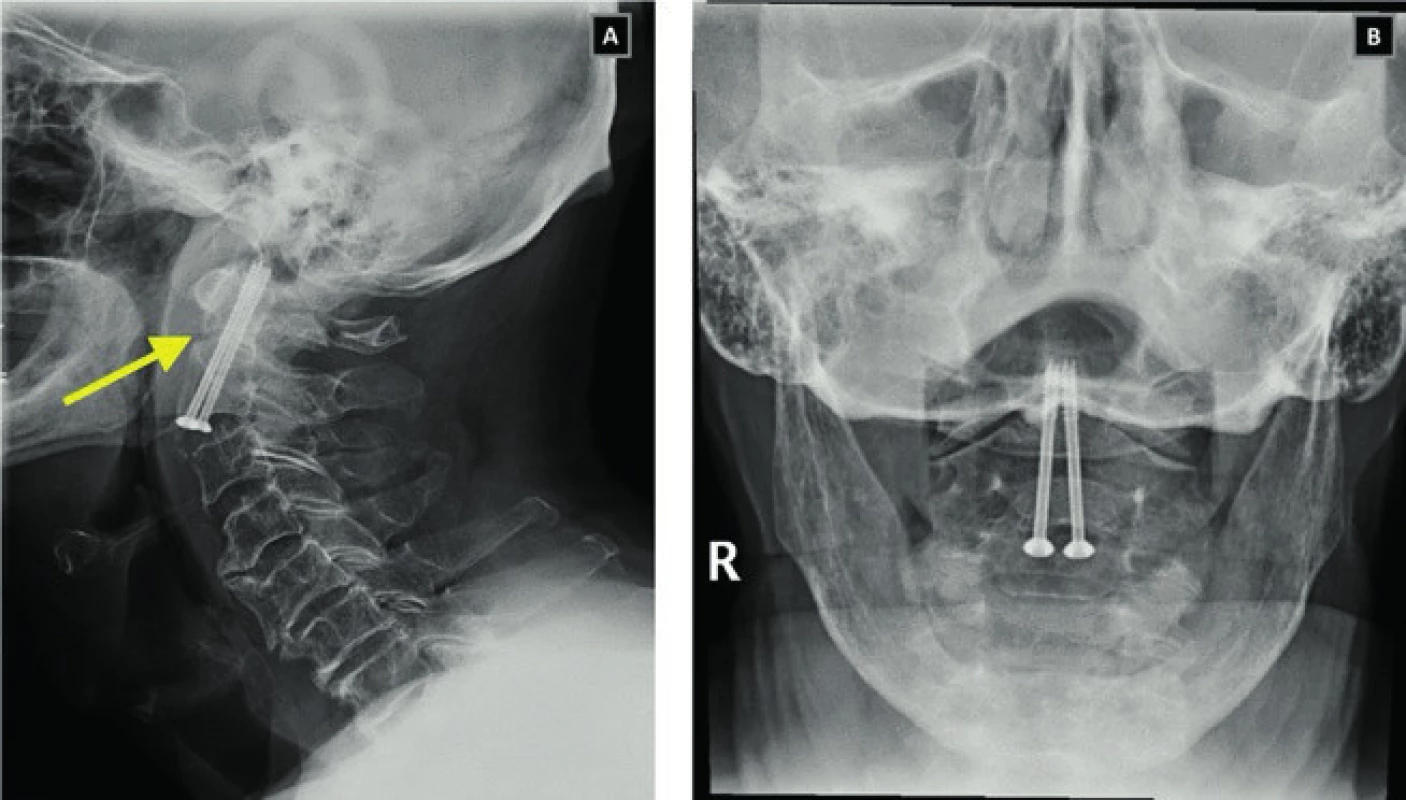

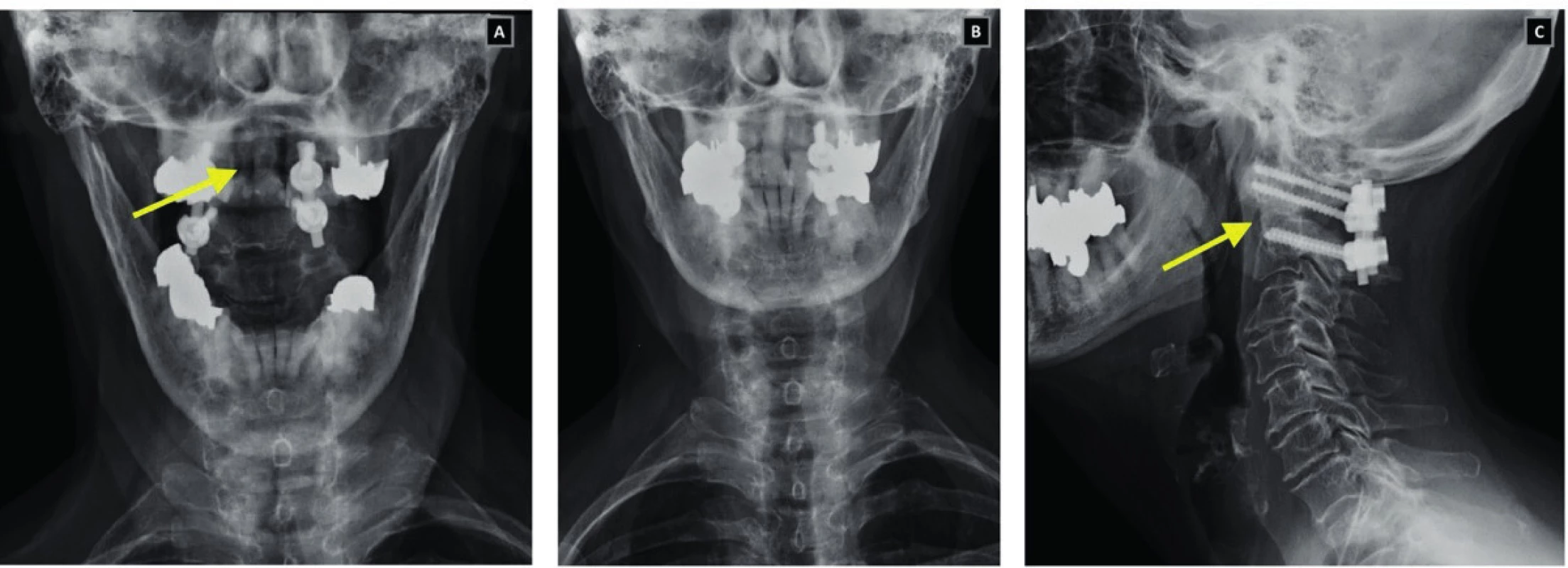

Surgical therapies in a form of direct osteosynthesis of the dens with 2 compression screws [2] (type II fracture), see Fig. 3 or with posterior C1-2 fusion according to Harms [5] (type III fracture), see Fig. 4, were primarily indicated for dislocated unstable fractures. The criterion for determining the fracture instability was the initial dislocation > 4 mm, dorsal dislocation of the dens by more than one half of its anteroposterior diameter, and angulation > 10°. The cervical spine was fixed after the surgery with a hard collar for 12 weeks in the case of direct osteosynthesis and for 6 weeks after the posterior fusion. Indication for surgical solution was considered with regard to age, character of the fracture and general health condition of the patient, who was indirectly evaluated based on an ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) classification [12]. Operating procedure in a form of internal osteosynthesis for dislocated odontoid fractures was contraindicated in patients achieving ASA=4 and the Halo brace was used for the fixation, see Fig. 5.

3. Cervical spine x-ray images in lateral (A) and transoral projection in a patient after direct compression odontoid osteosynthesis. The arrow shows the location of the fracture

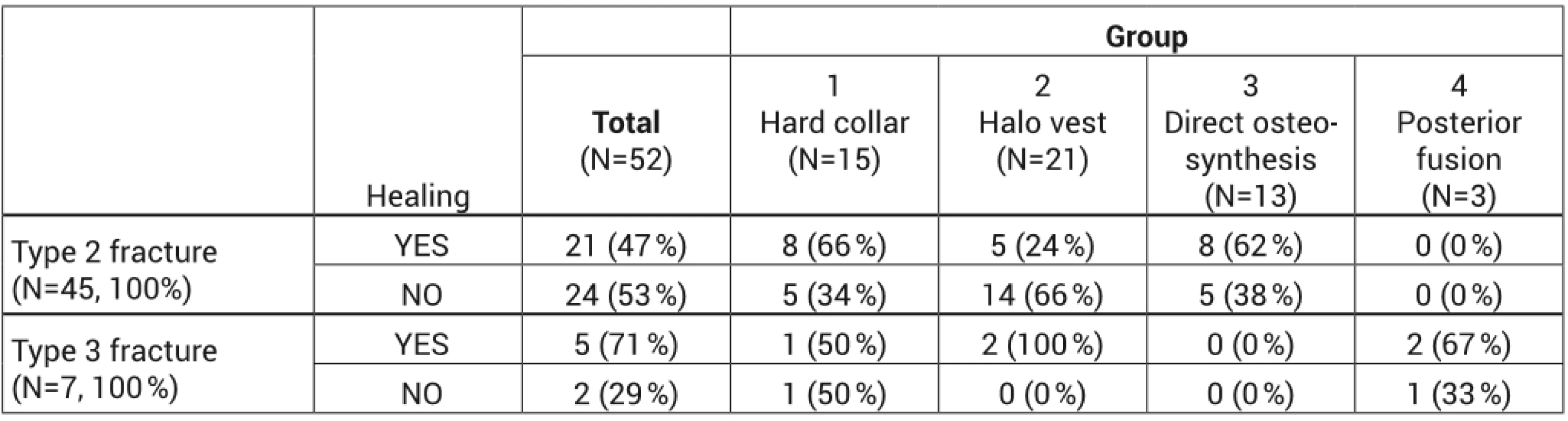

4. Cervical spine x-ray images in transoral (A), AP (B) and lateral (C) projection as well as images of a patient after posterior C1-2 fusion according to Harms. The arrow shows the location of the fracture

5. Cervical spine x-ray images in AP (A), transoral (B) and lateral (C) projection in a patient with the fracture of dens treated by means of the Halo fixation. The arrow shows the location of the fracture

Therapeutic results of both methods were evaluated in the criteria as follows: healing of the fracture after 6 months from the injury, occurrence and type of complications according to the therapy type chosen.

RESULTS

A total of 74 patients aged 65 and older with the fracture of dens axis were treated at the Trauma Clinic of the University Hospital in Brno from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2017. Out of the given number, 63 patients met the inclusion criteria (5 patients had type I fracture according to the A-A classification and 6 injured patients had the monitoring shorter than 6 months from the injury and they were disqualified from the evaluation); exclusive criteria were met by 11 patients (in 4 of them, the injury was associated with another vertebral injury cranially or caudally from the odontoid fracture, 5 patients were treated by a combination of 2 invasive methods for stabilisation of the odontoid fracture, and 2 patients suffered associated skeletal injuries limbs, which required additional operating treatment).

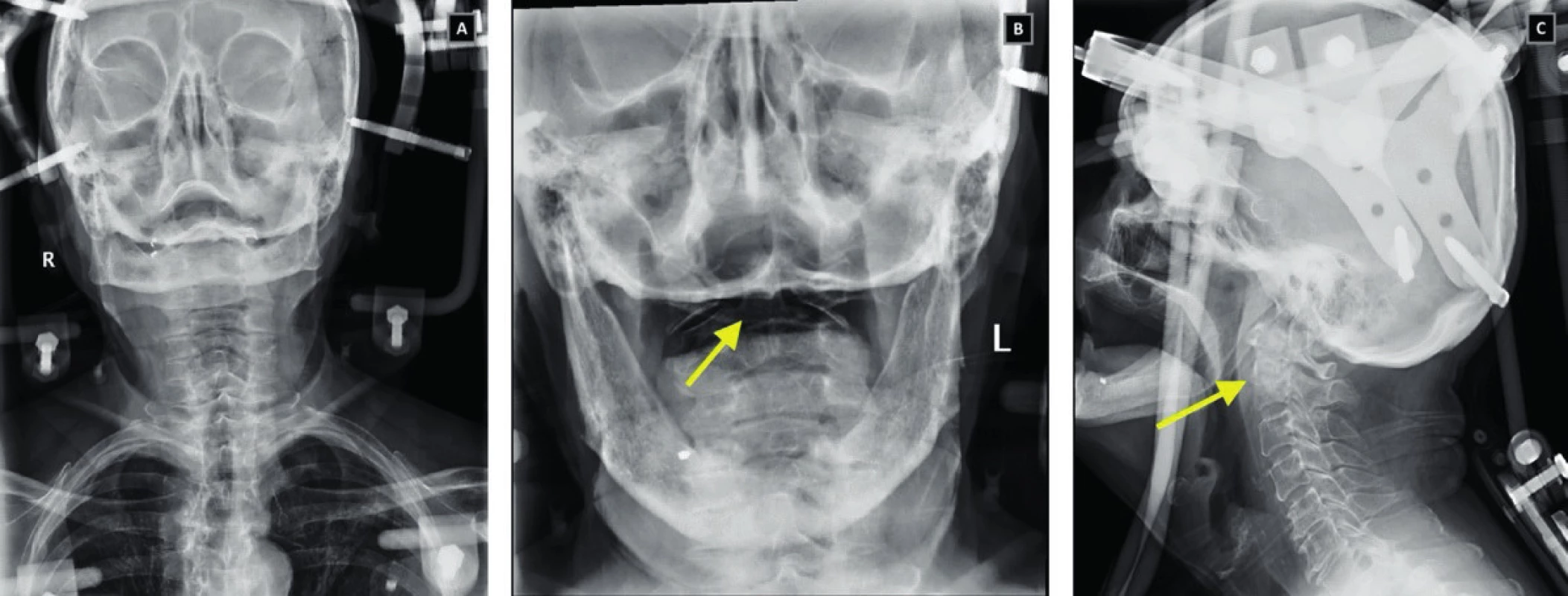

Following the satisfaction of the specified criteria, a total of 52 patients were finally enrolled for the study (28 women, 24 men) older than 65, who have suffered an insulated type II or type III fracture of dens axis according to the A-A classification. The average age of the set was 82 years (66–93 years), the median being 76 years. ASA classification in the set was within 2–4 range on the scale. The injury involved in all patients was a low-energy injury, typically a fall, mostly from the body height down on head or face. The set was subdivided into 4 groups according to the fracture fixation type applied. Group 1 (n=15, 29 %) consisted of patients with non-dislocated type II or III odontoid fracture, who were treated conservatively using a hard Philadelphia collar. Patients with dislocated type II or type III odontoid fracture, who were treated by closed reposition and stabilisation of the fracture using the Halo fixation (Bremer Halo system) were enrolled to Group 2 (n=21, 40 %). Group 3 (n=13, 25 %) consisted of patients with dislocated type II odontoid fracture, who were treated by direct compression osteosynthesis with cannulated titanium screws with 3.5 mm in diameter and 12 mm thread height (Johnson and Johnson). Patients with type III fracture treated by posterior C1–2 fusion according to Harms were enrolled in Group 4 (n=3, 6 %) table 1 provides detailed demographic data, fracture type and ASA classification.

1. Demographic data. ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, A-A = Anderson d‘Alonzo classification

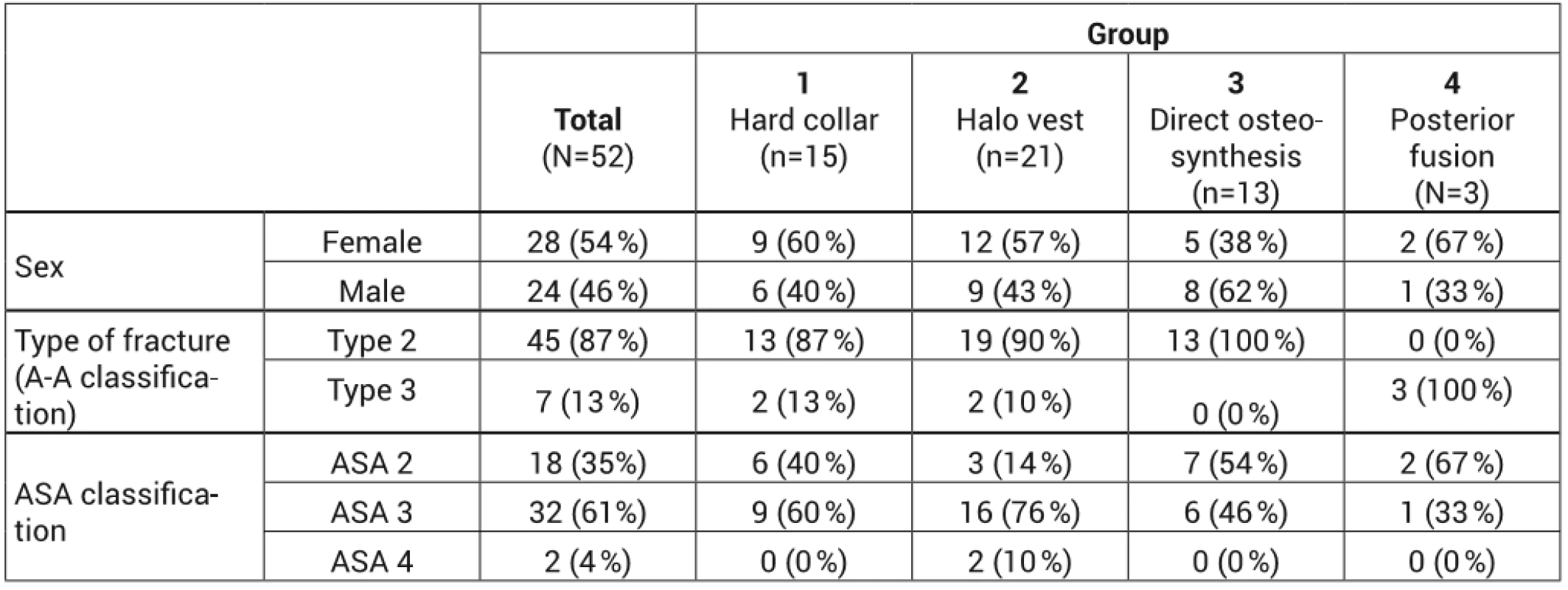

According to x-ray images, healing of type II odontoid fracture was observed after 6 months of treatment in 21 patients (47 %), where functional scans of the cervical spine did not show pathological dislocation of the dens and the fracture line was not present in the images. In the remaining 24 (53 %) patients, the fracture line persisted after 6 months of the treatment selected and the images in extension showed a pathological dislocation of the dens in 3 cases; however, no clinical correlate was present. Conservative procedure was chosen with regard to comorbidities, meaning recommended use of a soft collar for verticalization. In respect of type A III fractures, healing of the fracture was observed after 6 months of treatment in 5 cases (71 %). Detailed healing of the types of fracture according to the type of treatment used is provided in table 2.

2. Evaluation of the healing of dens axis depending on the fracture type and the therapy used

Besides non-healing of the fracture, we evaluated the other therapeutic complications individually as well. The fewest complications were represented in Group 1, i.e. Conservatively treated patients with hard collar where collar bruises at the point of support point (occiput and chin) were observed in 3 patients and an occipital pressure sore occurred in 1 patient. The most complications, on the other hand, were represented in Group 22, i.e. In a group of patients treated by the Halo fixation where pin track infection developed in 4 cases and it had to be reinserted with subsequent antibiotic therapy. Swallowing disorder developed in three patients during the treatment and in the end introduction of nasojejunal probe and enteral nutrition had to be used in one case. Also, pneumonia developed in 4 patients, most probably due to restriction of respiratory volume in consequence of the Halo vest applied. Repeated loss of reposition of odontoid fracture, which occurred in 11 patients (53 %), required repeated reposition and resulted in subsequent failed fracture healing, was evaluated by us as the most serious and most frequent complication of the Halo fixation treatment. In the group of patients treated by compress osteosynthesis we did not observe any early complications in any case; the performed osteosynthesis failed in 3 patients in consequence of cut-through of the inserted screws in the osteroporotic field. The given complication was resolved by extraction of the introduced osteosynthetic material and the fracture healing was completed using the hard collar. Dorsal fusion was not performed in these patients with regard to the fact that they belonged to the ASA 3 category, their average age was 82 years and another surgery would represent a high risk for them. Also, temporary swallowing problems occurred in 2 patients from Group 3, which completely subsided within 3 weeks from the surgery. In 1 case in Group 4 we reported superficial early infection, which was completely healed with local therapy. We did not observe any other complications.

DISCUSSION

Odontoid fractures represent a relatively frequent injury in the elderly population; for people age over 80 it is the most frequent injury of spine at all. A Swedish study of Brolin et al. even showed that the incidence of C2 vertebral fractures in the elderly population has been experiencing a long-term increase [3]. With regard to the aforementioned, there is a need for clear rules in the treatment of this type of injury in the elderly population. Unfortunately, at present there are no high-quality studies of the type I evidence level providing a basis for elaboration of a uniform therapeutic concept. On the one side there is a type of fracture that requires operating treatment (type II fractures have failure to heal described in 36 %) [1]. On the other side there is an elderly person with multiple comorbidities, for who an invasive surgery in the area of upper cervical spine represents a significant loading and also very high risk. Mortality accompanying the odontoid fracture is similar to that after proximal femoral fractures. 30-day mortality reported by the literature oscillates from 10 to 25 %, while one-year mortality achieves 20–50 % [7]. In our set, type II of the odontoid fracture was represented in 87 % of the patients, dislocation of the fracture being presented in most of them as well. In a young patient there would be a clear indication for an operating solution but, as we can see in our set, 89 % of the patients met the ASA classification criteria on level 3 or 4. Their perioperational risk was therefore high; that is why we chose less invasive treatment methods such as application of the Halo brace, which enabled to reposition the fracture and fix it in a more advantageous position. In our set, however, the application of halo brace showed high morbidity of patients in a form pin track infection, swallowing disorder or development of bronchopneumonia, which also corresponds with the results from literature that describe, among other things, 4times higher occurrence of bronchopneumonia associated with this type of fixation [16]. High percent of the loss of fracture reposition during the treatment, which was 53 % of the patients, was a big surprise; in consequence of this subsequent failure of the fracture to heal and formation of odontoid false joint occurred. However, none of the observed patients showed any neurological symptomatology and the resulting non-union was very well tolerated, which is in compliance with the works of Hanigan or Hart, who concluded that a stable ligament false joint is very well tolerated by the geriatric population [4, 6]. The method of direct compression osteosynthesis brought significantly higher percentage of healed fractures, but it was also aggravated by complications such as cut-through and migration of the inserted screws, which was caused by osteoporotic vertebral structure. We chose to extract the osteosynthetic material in our set with regard to the patients´ comorbidities. We completed the healing of two of these 3 patients with a hard collar and 1 patient was treated using the C1/2 anterior transarticular stabilisation method [9], which resulted in subsequent healing of the fracture. The method of cement-augmented screens can also be used to increase the stability or retention, as appropriate, of the screws in the performed direct osteosynthesis, which was published by Schwarz et al. [13] in his work. At the time of treatment of the set described we did not use the given method at our site.

We chose posterior C1-C2 fusion in patients with type III odontoid fracture, who were falling under the ASA classification 2 and 3 and were aged up to 75 years. The treatment resulted in the highest healing success rate in percentage terms (67 %); one patient with persisting fracture line in the area of dens did not report any problems and all patients tolerated the head rotation limitation very well, which corresponds with the work of Štulík et al. [15].

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of odontoid fracture in the elderly population has been growing and there is no uniform treatment concept for this injury. Each elderly patient requires a very individual approach with regard to the associated comorbidities of the elderly people. In respect of dislocated fractures it is always necessary to consider the risk and benefit of the operating procedure as well as the risk of subsequent morbidity when the Halo fixation is used. It should be kept in mind that even a stable ligament false joint is tolerated very well by the elderly people and where neurological symptomatology is absent, it is not always necessary to aim for bone healing of the fracture.

MUDr. Milan Krtička, PhD.

Sources

- ANDERSON, LD, DʼALONZO, RT. Fractures of the odontoid proces of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974, 56, 1663–1674.

- BOEHLER, J. Anterior stabilization for acute fractures and nonunions of the dens. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982, 64, 18–27.

- BROLIN, K., VON HOLST, H. Cervical injuries in Sweden, a national survey pf patients data from 1987 to 1999. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2002, 9, 40–52.

- HANIGAN, WC, POWEL, FC, ELVOOD, PW et al. Odontoid fractures in elderly patients. J Neurosurgery. 1993, 78, 32–35.

- HARMS, J., MELCHER, RP. Posterior C1-2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine. 2001, 26, 2467–2471.

- HART, R., SATERBAK, A., RAPP, T. et al. Nonoperative management of dens fracture nonunion in elderly patiens without myelopathy. Spine. 2000, 25, 1339–1343.

- CHAPMAN, J., SMITH, JS, KOPJAR, B. et al. The AO spine North America geriatric odontoid fractures mortality study. Spine. 2013, 38, 1098–1104.

- IYER, S., HURLBERT, JR, ALBERT, JT. Management of odontoid fractures in the elderly: A review of the literature and evidence-based treatment algorithm. Neurosurgery. 2018, 82, 419–430.

- KOČIŠ, J., KELBL, M. Selhání kompresní osteosyntézy zubu čepovce řešené přední transartikulární stabilizací C1/2. Kazuistika. Acta Chir Orthop Traum Čech. 2011, 78, 262–265.

- MALIK, SA, MURPHY, M., CONNOLLY, P. et al. Evaluation of morbidity, mortality and outcome following cervical spine injuries in elderly patients. Eur Spine J. 2008, 17, 585–591.

- OMEIS, DN., RUBANO, J. et al. Surgical treatment of C2 fractures in the elderly: multicenter retrospective analysis. J Spinal disord Tech. 2009, 22, 91–95.

- OWENS, WD, FELTS, JA et al. ASA physical status classifications: A study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978, 49, 239–243.

- SCHWARZ, F., LAWSON MA., WASCHKE, A. et al. Cement-augmented anterior odontoid screw fixation in elderly patients with odontoid fracture. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018, 175, 144–148.

- ŠTULÍK, J., ŠEBESTA, P., VYSKOČIL, T. Poranění krční páteře u pacientů nad 65 let. Acta Chir Orthop Traum Čech. 2007, 74, 189–194.

- ŠTULÍK, J., ŠEBESTA, P., VYSKOČIL, T. et al. Zlomeniny dentu u pacientů nad 65 let: přímá osteosyntéza dentu vs. zadní fixace C1-C2. Acta Chir Orthop Traum Čech. 2008, 78, 99–105.

- TASHJIAN, RZ, MAJERCIK, S., BIFFL, WL et al. Halo vest immobilization increases early morbidity and mortality in elderly odontoid fractures. J Trauma. 2006, 60, 199–203.

- WATANABE, M., SAKAI, D., YAMAMOTO, Y. et al. Upper cervical spine injuries: age-specific clinical features. J Orthop Sci. 2010, 15, 485–492.

Labels

Surgery Traumatology Trauma surgery

Article was published inTrauma Surgery

2020 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Stable osteosynthesis of pathological fracture of long bones in patients with multiple myeloma; retrospective evaluation of the therapy

- Nailing osteosynthesis of proximal humeral fractures

- Treatment of Rockwood type III acromioclavicular joint dislocation

- Odontoid fracture in the elderly, our therapeutic approach

- Trauma Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Treatment of Rockwood type III acromioclavicular joint dislocation

- Nailing osteosynthesis of proximal humeral fractures

- Odontoid fracture in the elderly, our therapeutic approach

- Stable osteosynthesis of pathological fracture of long bones in patients with multiple myeloma; retrospective evaluation of the therapy

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career