-

Medical journals

- Career

Diagnostic Challenges and Extraordinary Treatment Response in Rare Malignant PEComa Tumor of the Kidney

Authors: S. Huľová 1,3; Z. Sycova-Mila 1; D. Macák 2; P. Janega 4; Martin Chovanec 1; J. Mardiak 1; M. Mego 1

Authors‘ workplace: 2nd Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University, National Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 1; Department of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 2; 1st Department of Surgery, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovak Republic 3; Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University, National Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 4

Published in: Klin Onkol 2018; 31(6): 448-452

Category: Original Articles

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amko2018448Overview

Background:

Epithelioid angiomyolipoma (EAML) of the kidney, in contrast to classic benign renal angiomyolipoma, is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm with malignant potential. Representing a member of the perivascular epithelioid cells (PEComa) tumor family arising from the perivascular epithelioid cells, its accurate diagnosis and therapeutic approach remains challenging.

Methods:

We report a case of a patient with malignant EAML, initially treated as renal cell carcinoma (RCC) at our institution. In this paper, we briefly summarize current status of clinical and histopathological knowledge of renal PEComas with metastatic potential and reconsider the diagnostic and therapeutic approach in this particular case to highlight the risk of misdiagnosis, malignant potential of renal PEComas and to demonstrate an unexpected treatment response.

Results:

The patient in our case was diagnosed with chromophobe RCC with sarcomatoid features. She underwent a radical nephrectomy and epinephrectomy with a satisfactory postoperative history. Local recurrence urged chemotherapy commencement with sunitinib in the first line, and shortly afterwards, the patient was enrolled in a clinical trial with everolimus, with an extraordinary favorable treatment response for 30 months. Following the extirpation of single abdominal nodularity after 36 months of treatment with mTOR inhibitor, and proceeding the everolimus administration, the disease slowly progressed to the right liver lobe, resulting in right hemihepatectomy in another 24 months. The immunoprofile of liver metastases with positive staining of melanoma markers and smooth muscle markers induced the revaluation of the primary tumor and abdominal nodularity specimen to an invasive EAML of the kidney. Further disease progression was unavoidable despite several chemotherapy regimens, and the patient died 104 months after primary diagnosis.

Conclusions:

Renal tumors with adverse radiographic and histopathological features should become candidates for immunohistochemical staining as its omission frequently leads to a misdiagnosis, as showed in our case report. Atypical treatment response might suggest a possibility of a diagnostic mistake and should lead to reevaluation of the diagnostic and treatment process in the particular patient.

Key words:

renal PEComa – epithelioid angiomyolipoma – diagnosis – everolimus

Introduction

Epithelioid angiomyolipoma (EAML) of the kidney is a rarely diagnosed mesenchymal neoplasm with malignant potential, and it occurs sporadically or in association with tuberous sclerosis complex syndrome [1]. Renal angiomyolipomas (RAML) are considered a part of perivascular epithelioid cells (PEComa) tumor family, originating from perivascular epithelioid cells (which have no recognized non-malignant counterpart) [2]. These infrequent tumours are diagnosed predominantly in females and arise from gastrointestinal, urinary tract, retroperitoneum, female reproductive organs, abdomino-pelvic sites and skin. RAML and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis represent 2 major findings within the PEComa group [3].

Diagnosis of the epithelioid RAML remains challenging based upon its radiographic appearance and clinical presentation. Renal EAML may easily be misdiagnosed as renal cell carcinoma (RCC), renal sarcoma or medullary carcinoma. There is a strong evidence, supporting the key role of immunohistochemical evaluation in accurate diagnosis – PEComas typically stain for melanocyte (HMB45, Melan-A, MITF) and muscle cells markers (smooth muscle actin, myosin, calponin) and are negative for cytokeratins [4,5,6]. While most of the angiomyolipoma PEComas have benign nature, according to the literature, approximately 30% of all cases potentially develop into invasive renal EAMLs, characterized by aggressive growth and high risk of metastatic spread, resulting in poor prognosis. Current treatment approach for invasive EAML includes radical surgical procedure and mTOR signaling pathway targeted systemic therapy; however, optimal treatment strategy has not been established yet [7]. Herein, we present a case of patient with EAML of the kidney, initially diagnosed as RCC until dissemination, and treated with everolimus with unexpected positive response.

Clinical case details

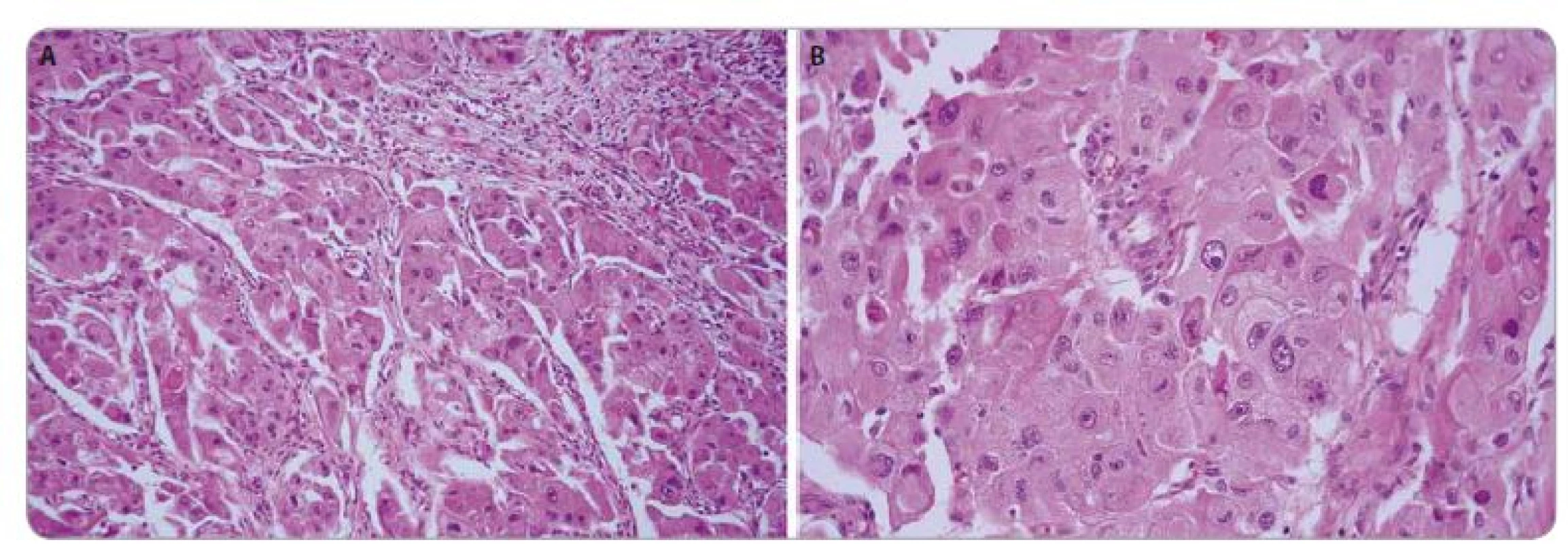

We present a case of 28-year-old Caucasian female with recently diagnosed ulcerative colitis. The suspicion for an expansive process of the right abdomen was expressed by the gastroenterologist as an external oppression of ascending colon and D3 (horizontal portion) duodenum was observed during the endoscopic examinations. CT and MRI scans revealed a multilocular capsulated tumor mass 11 × 15 × 14 cm (anterior-posterior dimension – AP × laterolateral dimension – LL × craniocaudal dimension – CC), encircling the right kidney, richly vascularized, with necrotic parts and intratumoral hemorrhages. The tumor was in close contact with segment 6 of the liver, with no signs of infiltration, no lymph nodes or distant sites were affected. The patient underwent a right radical nephrectomy and epinephrectomy, and the pathological examination revealed chromophobe RCC with sarcomatous features, nuclear grade 4. Following surgery, the patient had been closely monitored and disease-free for 15 months. Based on a CT-evidenced intra-abdominal recurrence, initial 6-month-period of treatment with sunitinib (50 mg/ day, 4 weeks on, 2 weeks off) had been commenced. Because of an early disease progression, she was enrolled into a clinical trial with everolimus for advanced RCC. The disease was stable for 36 months. Subsequently, she required a surgical extirpation of a single progressing omental metastasis. She continued everolimus therapy for another 24 months, when the disease gradually spread to the right liver lobe, segment 6 and 7, and resulted in right hemihepatectomy. The tissue was microscopically evaluated as malignant melanoma, and the cells were immunohistochemically characterized – CD10-, CK20-, RCC-, Hepatocyte-, TTF1-, S100+, Vimentin+, HMB45+, Melan A+, Ki67 30%. Regarding the unusual clinical behavior, treatment response to mTOR inhibitor and inconsistent histopathologic results, biopsies from primary tumor, abdominal nodule and liver metastases were redefined to metastasizing epithelioid RAML (Fig. 1, 2). The patient proceeded in treatment with everolimus for another 3 months; however, she experienced a severe disease dissemination to the lungs with pleural effusion as well as to the liver and intraabdominally. Subsequently, several lines of systemic therapy (5-flurouracil/ calcium leucovorine, gemcitabine, paclitaxel + carboplatin, vinorelbine) were administered without treatment response and the patient died 104 months after diagnosis.

1. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the kidney. The histological image was characterized by epithelioid morphology of tumor cells, with enlarged atypical nuclei and prominent nucleoli. HE, 200× (A), 400× (B).

2. Immunohistochemical profi le of the tumor. Tumor cells were negative for cytokeratins AE1/3 (A) and CD10 (B), focally positive for vimentin (C), and showed typical cytoplasmic positivity for Melan A (D) and HMB45 (E). The cells showed also cytoplasmic MyoD1 (F) positivity reported in these tumors [15]. IHC-Px-DAB, 400×. ![Immunohistochemical profi le of the tumor.

Tumor cells were negative for cytokeratins AE1/3 (A) and CD10 (B), focally positive for vimentin (C), and showed typical cytoplasmic positivity

for Melan A (D) and HMB45 (E). The cells showed also cytoplasmic MyoD1 (F) positivity reported in these tumors [15]. IHC-Px-DAB, 400×.](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image_pdf/9477a58c31f7e37b27dee2ae1b703bb1.jpeg)

Discussion

Perivascular epithelioid cell line was firstly described by Apitz in 1943, and it was designated as an abnormal myoblast in RAML [8]. In 2010, the World Health Organization introduced the definition of the PEComas as mesenchymal tumors composed of histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells [9].

Two major findings of the PEComa family are RAML and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The first mentioned represents a rare soft tissue tumor and may demonstrate malignant potential. It occurs sporadically (50– 70% of all cases) or it is associated with genetic alterations of tuberous sclerosis complex, an autosomal dominant congenital disease caused by the loss of heterozygosity in the TSC1 region (9q34) or TSC2 region (16p) [1,10,11]. It has been recognized that tuberous sclerosis complex genes are involved in mTOR signaling pathway [10]. During the last 2 decades, more than 160 cases of angiomyolipoma PEComas have been published worldwide [6], identifying 3 major challenges of their management: diagnostic accuracy, necessity of risk stratification and determination of treatment strategies. Diagnostic process of EAML PEComa remains challenging. Given the histological evaluation, it may easily be confounded with RCC, renal sarcoma or melanoma [2,4]. The crucial role of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of renal EAML has been proven by numerous sources, including our clinical case, and should be considered especially in the presence of adverse features. Based on evidenced data, malignant PEComas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of large, well-circumscribed renal tumors with intratumoral hemorrhages and necrotic areas, predominantly if coagulative tumor necrosis, nuclear atypia and atypical mitosis are seen histologically [12,13]. The positivity of smooth muscle markers and melanoma markers are typical in most of renal PEComas. Moreover, current relevant data illustrate the need of EAMLs malignant potential assessment. EAMLs are extremely rare and account for approximately 5% of surgically removed angiomyolipomas [7]. The metastatic spread is observed among 20– 30% of patients, and most frequently affected sites are liver, lungs and peritoneum [11,14]. The criteria for malignant potential of EAML have not been established yet. Therapeutic approach includes radical surgical procedure; regarding systemic treatment, mTOR inhibitors administration has shown promising results. Despite of primarily inaccurate diagnosis, the patient in this report benefited from mTOR inhibitor treatment and exhibited an extraordinary favorable response.

Conclusion

The tumors belonging to the PEComa family are not seen frequently, and their diagnostic and therapeutic management could be challenging. By reporting our clinical case, we point at increasing awareness about the possibility of PEComa occurrence and misdiagnosis, and emphasize the role of immunohistochemical examination in EAML. Secondly and equally important, we encourage the specialists to keep close attention to the clinical course of the disease, and in case of extraordinary treatment response, reconsider the primary finding and approach. Clinical evidence regarding renal EAML is emerging. Nevertheless, further investigation is needed to proceed in optimization of the medical care standards for patients with rare PEComas of the kidney.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE recommendation for biomedical papers.

Submitted: 12. 09. 2018

Accepted: 17. 10. 2018

MUDr. Soňa Huľová

2nd Department of Oncology

Faculty of Medicine

Comenius University

National Cancer Institute

Klenová 1

833 10 Bratislava

Slovak Republic

e-mail: sonahulova@gmail.co

Sources

1. Kuroda N, Pan CC. Renal angiomyolipomas: clinical and histological spectrum. Urol Sci 2011; 22(1): 40– 42.

2. Esheba Gel S, Esheba Nel S. Angiomyolipoma of the kidney: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 2013; 25(3): 125– 134. doi: 10.1016/ j.jnci.2013.05.002.

3. Hwang HC, Hwang, JI, Hung SW et al. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma: an overview of five cases with the concept of PEComa. Chin J Radiol 2008; 33 : 253– 260.

4. Grant C, Lacy JM, Strup SE. A 22-year-old female with invasive epithelioid angiomyolipoma and tumor thrombus into the inferior vena cava: case report and literature review. Case Rep Urol 2013; 2013 : 730369. doi: 10.1155/ 2013/ 730369.

5. Cao QH, Liu F, Xiao P et al. Coexistence of renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma and clear cell carcinoma in patients without tuberous sclerosis. Int J Surg Pathol 2015; 20(2): 196– 200. doi: 10.1177/ 1066896911413576.

6. Singer E, Yau S, Johnson M. Retroperitoneal PEComa: case report and review of literature. Urol Case Rep 2018; 19 : 9– 10. doi: 10.1016/ j.eucr.2018.03.012

7. He W, Cheville JC, Sadow PM et al. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the kidney: pathological features and clinical outcome in a series of consecutively resected tumours. Mod Pathol 2013; 26(10): 1355– 1364. doi: 10.1038/ modpathol.2013.72.

8. Apitz K. Die geschwulste und Gewebsmissbildungen Nierenrinde. II Midteilung Die mesenchymalen Neubildungen. Virchows Arch 1943; 31 : 306– 327.

9. Wildgruber M, Becker K, Feith M et al. Perivascular epitheloid cell tumor (PEComa) mimicking retroperitonea liposarcoma. World J Surg Oncol 2014; 12 : 3. doi: 10.1186/ 1477-7819-12-3.

10. Pan CC, Chung MY, Ng KF et al. Constant allelic alteration on chromosome 16p (TSC2 gene) in perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa): genetic evidence for the relationship of PEComa with angiomyolipoma. J Pathol 2008; 214(3): 387– 393. 10.1002/ path.2289.

11. Jayaprakash PG, Mathews S, Azariah MB et al. Pure epithelioid perivascular cell tumour (epithelioid angiomyolipoma) of kidney: case report and literature review. J Cancer Res Ther 2014; 10(2): 404– 406. doi: 10.4103/ 0973-1482.136672.

12. Kenerson H, Folpe AL, Takayama TK et al. Activation of the mTOR pathway in sporadic angiomyolipomas and other perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol 2007; 38(9): 1361– 1371. doi: 10.1016/ j.humpath.2007.01.028.

13. Tirumani SH, Shinagare AB, Hargreaves J et al. Imaging features of primary and metastatic malignant epithelioid cell tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 202(2): 252– 258. doi: 10.2214/ AJR.13.10909.

14. Chuang CK, Lin HC, Tasi HY et al. Clinical presentations and molecular studies of invasive renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma. Int Urol Nephrol 2017; 49(9): 1527– 1536. doi: 10.1007/ s11255-017-1629-4.

15. Panizo-Santos A, Sola I, de Alava E et al. Angiomyolipoma and PEComa are immunoreactive for MyoD1 in cell cytoplasmic staining pattern. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2003; 11(2): 156– 160.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2018 Issue 6-

All articles in this issue

- Consequences of Hypoacidity Induced by Proton Pump Inhibitors – a Practical Approach

- Urinary Tract and Gynecologic Malignancies

- Effect and Toxicity of Radiation Therapy in Selected Palliative Indications

- Undifferentiated Carcinoma of the Pancreas – a Case Report

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Estrogen Receptors and ALK Positivity

- Long Non-Coding RNA Signature in Cervical Cancer

- Infiltration of Prostate Cancer by CD204+ and CD3+ Cells Correlates with ERG Expression and TMPRSS2-ERG Gene Fusion

- Down-regulation of TSGA10, AURKC, OIP5 and AKAP4 genes by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus crispatus SJ-3C-US supernatants in HeLa cell line

- Use of the Metal Deletion Technique for Radiotherapy Planning in Patients with Cardiac Implantable Devices

- Diagnostic Challenges and Extraordinary Treatment Response in Rare Malignant PEComa Tumor of the Kidney

- Animal-Type Melanoma – a Mini-Review Concerning One of the Rarest Variants of Human Melanoma

- Influence of Gastrointestinal Flora in the Treatment of Cancer with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Undifferentiated Carcinoma of the Pancreas – a Case Report

- Effect and Toxicity of Radiation Therapy in Selected Palliative Indications

- Consequences of Hypoacidity Induced by Proton Pump Inhibitors – a Practical Approach

- Diagnostic Challenges and Extraordinary Treatment Response in Rare Malignant PEComa Tumor of the Kidney

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career