-

Medical journals

- Career

Czech National Cancer Screening Programmes in 2010

Authors: O. Májek 1; J. Daneš 2; M. Zavoral 3; V. Dvořák 4; Š. Suchánek 3; B. Seifert 5; P. Kožený 6; S. Pánová 7; L. Dušek 1

Authors‘ workplace: Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 1; Department of Radiodiagnostics, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 2; Department of Internal Medicine, Charles University, First Faculty of Medicine, Central Military Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic 3; Czech Gynecological and Obstetrical Society, Brno, Czech Republic 4; Department of General Medicine, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 5; National Reference Centre, Prague, Czech Republic 6; Ministry of Health Care, Prague, Czech Republic 7

Published in: Klin Onkol 2010; 23(5): 343-353

Category: Original Articles

Overview

Backgrounds:

All three cancer screening programmes recommended by the Council of the EU are available to defined target age groups in the Czech Republic. Organized programmes for screening of breast, colorectal and cervical cancer have been initiated in the last decade.Materials and Methods:

A system for information support, as an essential component of organized screening programmes, has been implemented in all screening programmes. It comprises the Czech National Cancer Registry to monitor the cancer burden and population impact of the programmes, the National Reference Centre as a provider of nationwide insurance claims data, and the specialised databases of all three programmes, which collect information on screening, diagnostics and final diagnoses.Results:

Early diagnostics of malignant neoplasms and progress in therapy have helped to stabilize mortality, even in diagnoses with increasing incidence. The coverage of the Czech screening programmes has constantly been rising; however, it is still insufficient: 51.2%, 17.9% and 48.4% of the target population was covered at the end of 2008 in breast, colorectal and cervical screening programmes, respectively. In 2008, a total of 468,419 women underwent screening mammography and 2,128 tumours were detected (4.5 per 1,000 screened). According to the screening colonoscopy registry, more than 13,000 men and women underwent preventive colonoscopy in 2009, 4,085 patients were diagnosed with adenoma and 619 with colorectal cancer, mostly in the early stages. The information system for cervical screening was implemented in 2009 and has been running in pilot mode; the first results are expected at the end of 2010.Conclusion:

The system for information support within organised cancer screening programmes enables monitoring of the performance of screening and diagnostic centres and thus helps to maintain continuous quality improvements, which are a necessary presumption for replicating the promising results of clinical trials. To achieve a substantial impact on population incidence and mortality, a large increase in test coverage in target populations will be necessary. The programmes should be transformed to a population-based form, which involves inviting all people in the target population to be screened.Key words:

cancer screening – malignant neoplasms – information systemBackgrounds

With regards to evidence from clinical and epidemiological studies, the Council of the European Union recommends cervical cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer screening to be offered to citizens of the European Union by its member states [1].

Breast cancer screening with mammography can decrease breast cancer mortality in target population by 25 – 30% [2], as demonstrated in randomised controlled trials in the United States and Europe and in several meta analyses; the results were successfully replicated in many European programmes: Denmark [3], Finland [4], Iceland [5], Italy [6], the Netherlands [7], Spain [8], Sweden [9,10] and United Kingdom [11].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with annual guaiac faecal occult blood test (gFOBT) was demonstrated to decrease the CRC mortality by 33 percent in U.S. randomized trial [12]. European trials showed reduction of the CRC mortality by 15% [13] and 18% [14] with biennial gFOBT. The reduction persisted after 9 rounds and reached 43% in all rounds participants [15], emphasising importance of regular attendance by participants. Including also the unpublished results of the Göteborg trial, the mortality reduction of 16% was estimated in Cochrane systematic review [16]. Annual or biennial FOBT screening also significantly decreases CRC incidence [17]. Immunochemical faecal occult blood test (iFOBT) seems to have even better performance than gFOBT [18,19] and first promising results from randomized trials have been published [20]. Colonoscopy seems to be a powerful screening tool, with estimated decrease of CRC incidence up to 90% [21 – 24]; however, direct evidence is necessary to estimate its effectiveness [25]. The low risk of CRC after colonoscopy persists for more than 10 years [26 – 28], which potentially enables a long interval between screening examinations.

Screening for cervical cancer based on cytology was not evaluated using randomized controlled trial assessing decrease in the disease mortality and evidence was derived from cohort and case control studies [29]. Nevertheless, these observational studies showed outstanding decrease in cervical cancer incidence by up to 80% [30]. Decrease in mortality ranging from 25 – 80% was confirmed in the subsequent international study [31]. This study also confirmed that unorganized cervical cancer screening may completely fail to show the outlined benefit. Finnish case control study comparing organised and spontaneous pap smear screening concluded that the latter is less effective, costs more and results in more harm in screened women [32].

Organization is equally important in breast and colorectal cancer screening as well. IARC Handbooks of cancer prevention [29,33] state six characteristics of organised screening programme: a policy specifying target population, screening method and interval; a defined target population; a team responsible for overseeing screening centres; a decision structure and responsibility for health care management; a quality assurance system utilizing relevant data; and a monitoring of cancer occurrence in target population.

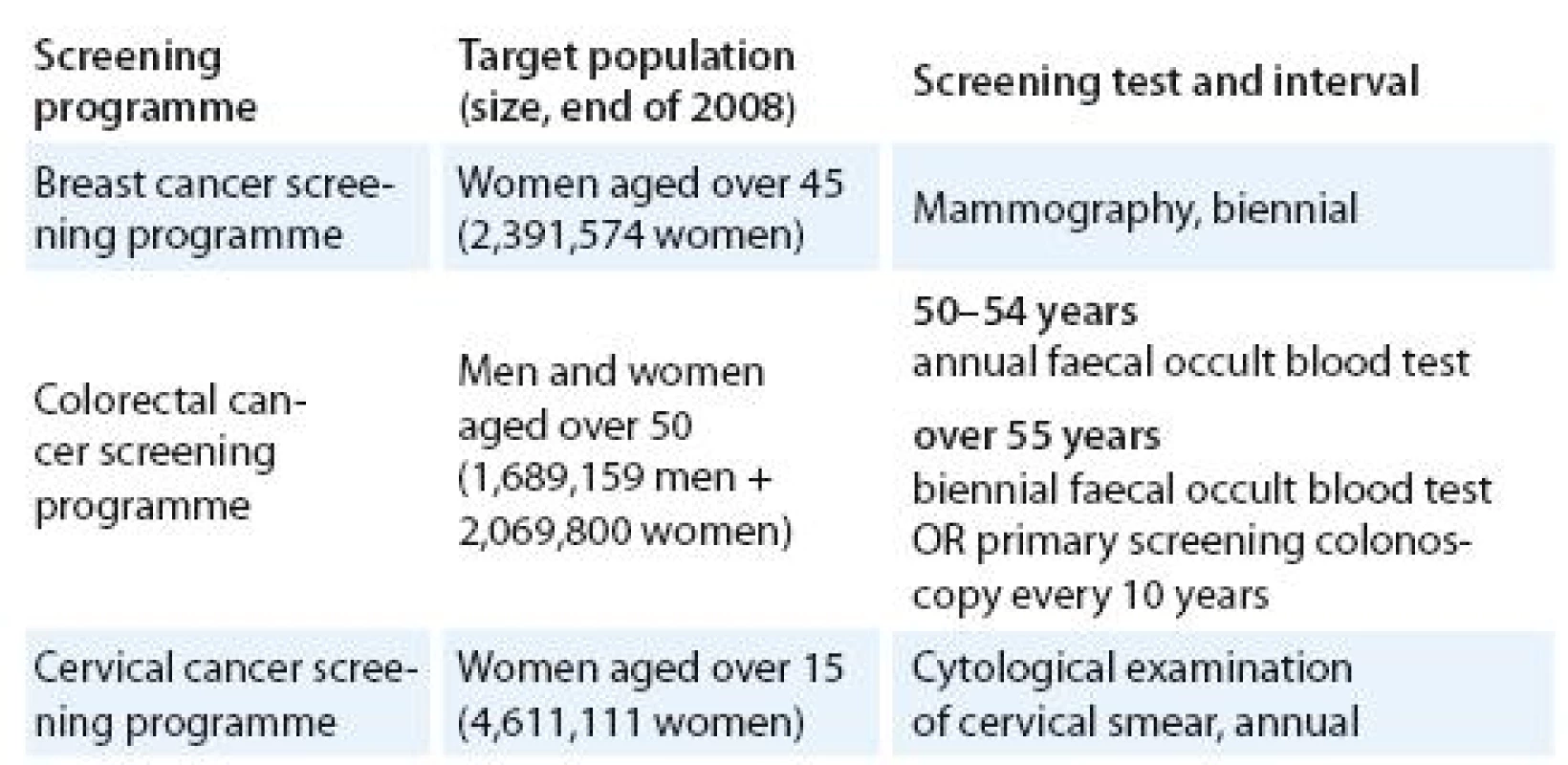

Cancer screening programmes have been implemented in most countriesof the European Union [34]. In the Czech Republic, recommended screening modalities were offered to target population even before publication of the Council Recommendation. However, large efforts to organize the screening programmes have been undertaken just recently and led to complete offer of screening modalities, as recommended by the Council, and proper monitoring of the screening process (Tab. 1, Fig. 1 – 3).

1. Screening tests and target populations in the Czech cancer screening programmes.

Fig. 1. Scheme of breast cancer screening process in the Czech Republic.

Fig. 2. Scheme of colorectal cancer screening process in the Czech Republic.

Fig. 3. Scheme of cervical cancer screening process in the Czech Republic.

This article summarizes the status and latest results of all three cancer screening programmes in the Czech Republic and outlines potential future improvement. The results are generated from unified information system, which is implemented in all screening programmes.

Material and methods

The system for information support is a vital part of organized screening programmes. Czech system for the information support facilitates effective configuration and monitoring of screening process and outcomes. Its components include monitoring of cancer epidemiology, performance monitoring of screening centres and monitoring of screening programme using administrative data (Fig. 4). The system is operated by an independent academic body – Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses of Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic.

Fig. 4. System for information support in the Czech national cancer screening programmes – components, administrators and objectives.

The Czech National Cancer Registry (CNCR) is an essential source of cancer burden data. Registration of cancer cases is obligatory and stipulated by the legislation; the registry therefore covers the entire population of the Czech Republic since 1976. CNCR can be combined with demographic data and with Death Records Database, provided by the Czech Statistical Office, and thus enables to estimate disease incidence and mortality, monitor distribution of clinical stages, cancer treatment, survival, etc. Information on cancer epidemiology are available on line for wide public at http:/ / www.svod.cz [35].

The system of mammodiagnostic scree-ning centres was established in 2002 [36],at the same time when the programme started. These centres regularly send data to the Breast Cancer Screening Registry. This database includes information on screening mammography, additional imaging or invasive diagnostic procedures and final diagnosis. Reporting of screening performance indicators according to European Guidelines [37] is provided to ensure high quality and efficiency of the programme.

After pilot studies on colorectal cancer screening feasibility performed in the Czech Republic both before [38] and after fall of the communist regime in 1989, organized service screening programme was initiated in 2000 [39,40] using biennial FOBT as a screening test. Starting from 2009, primary screening colonoscopy has been introduced as a screening test [41]. Therefore, persons aged over 55 years can now attend a gastroenterologist directly to obtain their colonoscopy, without need for prior positive FOBT test.

A pilot organized collection of records on screening colonoscopy examination after positive FOBT was initiated in 2007. The data collected in the Screening Colonoscopy Registry include information on macroscopic and microscopic results of colonoscopy, final diagnosis and information on adverse events during the procedure. Monitoring of screening performance was proposed in colorectal cancer screening [42]. U.S. review prioritized two performance measures in colonoscopy: caecal intubation rate and adenoma detection rate [43], which are measurable, apart from many others, in the Screening Colonoscopy Registry. Adenoma detection rate has been recently proven to directly affect interval cancer rate, and therefore programme sensitivity [44].

Pilot collection of records on screening cervical cytology was initiated in 2009 by establishing the Cervical Cancer Screening Registry (CCSR). The collected data include information on screening examination, its results and results of indicated histopathology examination. Such data should provide a basis for performance evaluation according to the European Guidelines [45].

In the Czech Republic, most of the medical procedures relevant to secondary cancer prevention are reimbursed within public health insurance. After aggregation of the data by the National Reference Centre (NRC), it is possible to use these health insurance data in monitoring of the screening programmes. The breast cancer screening programme can use the data for verification of information obtained by its own information system. Besides that, data can be extracted to credibly estimate prevalence of opportunistic screening examinations. Health insurance data contains information on all faecal occult blood tests performed. Therefore, this data source can reliably supplement individual information systems to obtain complete picture of the screening process. In a similar fashion, health insurance data can be employed in cervical cancer screening as well.

Incidence of invasive breast cancer has been rising in the Czech Republic since the early 1990s and peaked in 2003, when prevalent round of breast cancer screening occurred (Fig. 5). Breast cancer is an example of cancer diagnosis with successfully improving early detection (Fig. 6). Further improvement occurred after initiation of breast cancer screening programme. Coverage by screening mammography gradually increased in 2002 – 2008 and recently exceeds 50% for two year period 2007 – 2008 (Fig. 7). However, no decreasing trend is observable in breast cancer mortality, which remains stable over 1990s and 2000s (Fig. 8).

Fig. 5. Incidence of cancer diagnoses targeted by cancer screening programmes. Sources of data: Czech National Cancer Registry, Czech Statistical Office.

Fig. 6. Distribution of clinical stages in newly diagnosed breast cancer cases. Source of data: Czech National Cancer Registry; *objective reasons: DCO, cases diagnosed by autopsy, early deaths, therapy not initiated due to objective reasons etc.

Fig. 7. Coverage of the target population by screening programmes. Sources of data: Czech Statistical Office, National Reference Centre, Breast Cancer Screening Registry.

Fig. 8. Mortality of cancer diagnoses targeted by cancer screening programmes. Sources of data: Czech National Cancer Registry, Czech Statistical Office.

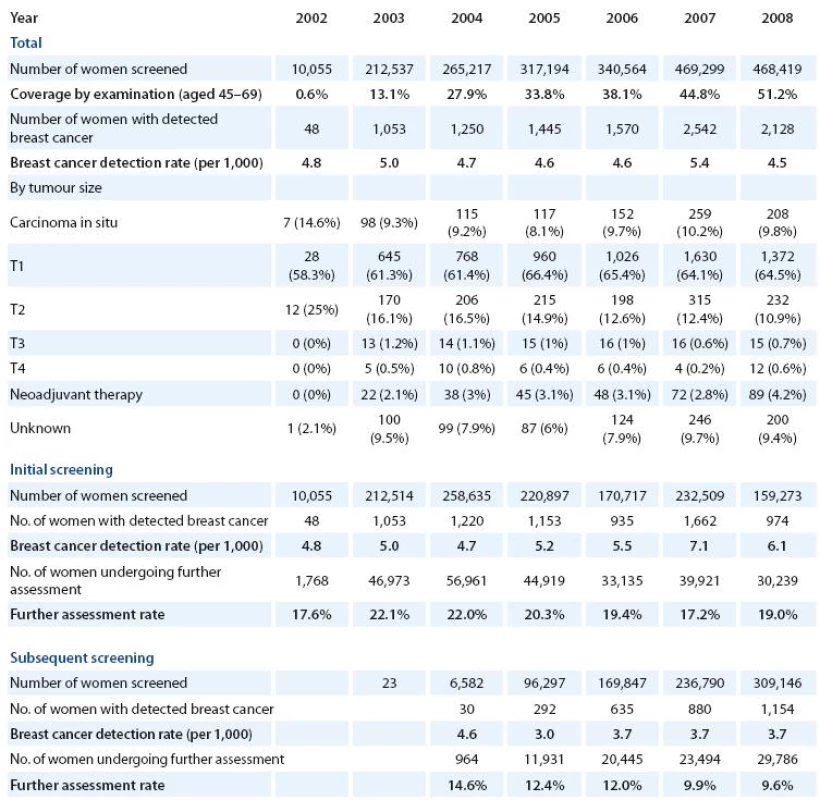

The Breast Cancer Screening Registry allows the monitoring of the screening process using key performance indicators. Total of 468,419 women underwent screening examination in 2008. Breast cancer detection rate (number of breast cancer cases detected per 1,000 women screened) is an indirect indicator of mammography sensitivity. In 2008, 6.1 breast cancers were detected in 1,000 women initially screened. This number decreases in women attending their subsequent screening examination: 3.7 breast cancers were found per 1,000 screened women. Over 70% of tumours detected in the screening programme are in situ cases or invasive cases smaller than 2 cm (pT1). Further assessment rate (proportion of women undergoing additional diagnostic examination after positive result of screening test) is rather decreasing in initially and subsequently screened women, showing improving specificity of the screening test and therefore better efficiency of the programme; however, it still remains high compared to organised programmes abroad (Tab. 2).

2. Results of breast cancer screening programme. Sources of data: Czech Statistical Office, Breast Cancer Screening Registry.

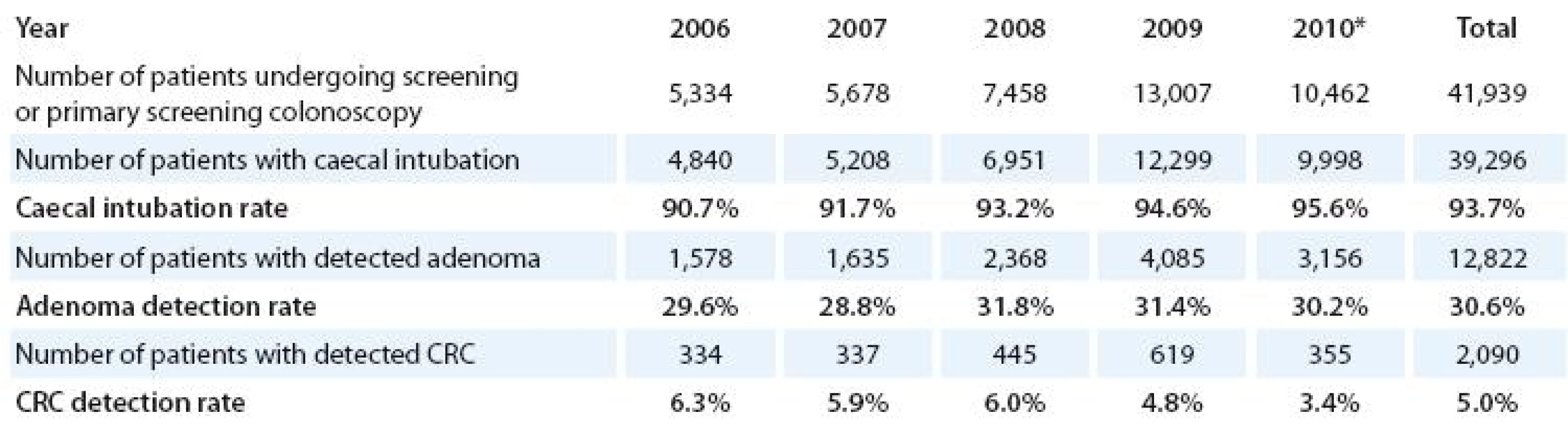

Despite operation of the organized screening programme, the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer has been very stable in recent years (Fig. 5, 8). Reason for the lack of effect on population cancer burden is certainly a low participation of the target population at the screening examination (Fig. 7) – only 18% proportion of the target population was screened in 2007 – 2008. Screening colonoscopy registry, however, shows very promising development in number of screening and primary screening colonoscopies in the target population (Tab. 3). The number of men and women undergoing colonoscopy almost doubled in 2009 compared to previous year. Caecal intubation rate constantly increases and reaches 95.6% in 2010. During period 2006 – 2010 (preliminary results), 12,822 patients were diagnosed with adenoma and 2,090 with colorectal cancer. One half of the adenoma patients were diagnosed and treated for advanced adenoma, which would have significant risk of progression to colorectal cancer if untreated. About 20% of patients with colorectal cancer are diagnosed with advanced stage III – IV disease, compared to about 50% in population cancer registry. Screening programme is therefore able to detect colorectal cancer earlier or even to prevent the disease in patients through removing high risk adenomas.

3. Results of colorectal screening and primary screening colonoscopies. Source of data: Screening Colonoscopy Registry; *preliminary data.

Despite the long time utilization of preventive cervical cytology examinations, incidence and mortality of cervical cancer has not been changing in the Czech Republic. Incidence rate of approximately 20 cases per 100,000 women has been observed for almost 30 years (Fig. 5). No time trend is observable in mortality rate (Fig. 8). About 50% of the woman target population attends regular annual gynaecological check up with collection and cytological examination of cervical smear (Fig. 7). Comprehensive results from Cervical Cancer Screening Registry on performance of screening cytology will be available at the end of 2010. Thorough monitoring will hopefully help to improve screening performance with more apparent impact on cervical cancer burden.

Discussion

The Czech Republic ranks among countries with highest cancer burden in the world. Latest IARC database [46] even shows the Czech Republic to have the highest male colorectal cancer incidence worldwide. During 1990s and 2000s, the incidence of breast and colorectal cancer was constantly increasing. Apart from apparent ageing of the Czech population, this increase could be probably attributed to transition towards ‘westernized’ lifestyle, e. g. changes in reproductive behaviour (breast cancer), increased consumption of sugar, red meat or decreased physical activity (colorectal cancer) [47]. Absence of organized, population based cervical cancer screening programme precluded significant decrease in cervical cancer incidence and mortality similar to Scandinavian countries [31,48].

System for information support was developed to facilitate monitoring of performance measures, as recommended by the EU Council [1], IARC [29,33] and the European Commission in official Guidelines [37,45]. Adhering to common definitions of process measures enables comparison to guideline targets and reports published on performance of organized screening programmes abroad (e. g. [49 – 51]). Similarly, the screening performance, as measured by defined indicators, is a necessary prerequisite to replicate promising results of randomized controlled trials in preventing death from cancer [52].

In addition to data based monitoring of well organized screening programmes, controlled in the network of accredited screening centres, the attendance of target population is the most important task.

To increase coverage by breast cancer screening, the pilot project for centralized invitation of non attendees was undertaken in the Czech Republic in 2007 – 2008 by the General Health Insurance Company. Although the overall participation rate after invitation was rather low, this project helped the mammography coverage to exceed 50% level in 2007 – 2008. The coverage improved particularly in elder age groups of women and confirmed that transformation to population based programme inviting every eligible person will be necessary to increase participation to 70% or more, as it is usual in successful programmes in western and northern Europe [49,53,54].

Women over 70 years of age were also invited during the pilot project in order to assess characteristics of screening process in this age group. High rates of detection and low further assessment rates were observed in women over 70 years of age, promising high quality and good effectiveness of performed examinations. Following progress in the Netherlands [55], where the upper age limit for invitation to breast cancer screening was set to 75 years, and in England, where women can continue to request routine mammography every three years after they reach 70 years of age, the Czech Republic has extended the upper age limit for access to screening mammography since 2010.

Not all colorectal cancer screening tests are acceptable for all men and women and it is therefore important for improving uptake to consider patients’ preference [56]. Accordingly, starting in January 2009, primary screening colonoscopy and annual FOBT were offered to the Czech target population. Improved participation could be also expected with wider use of iFOBT instead of gFOBT [57] and with involvement of gynaecologists to recruit women, starting in 2009.

Information strategy and dissemination of information on cancer risk and potential benefits of screening are equally important. As a principal source of information on breast, colorectal and cervical cancer prevention, national web portals www.mamo.cz, www.kolorektum.cz and www.cervix.cz were launched to enable communication with wide public and also health professionals offering cancer screening examinations. Combining direct invitation with mass media campaigns seems to be the most successful strategy to improve attendance in cancer screening programmes [58], celebrity promotional campaign can also help to substantially improve participation [59].

Conclusion

All three cancer screening programmes with evidence on effectiveness are available in the Czech Republic. Programmes are organized, with strictly defined screening test, interval and target population, and with nominated network of screening centres based on quality assurance. Data on screening tests and outcome diagnoses are collected in the system for information support, which thoroughly monitors the screening process and maps cancer burden and impact of the prevention. This system ensures quality comparable to clinical trials, which is necessary to achieve effectiveness observed in successful screening programmes abroad. To achieve substantial impact, significant increase in attendance is necessary. This should be facilitated by transformation to population based programmes with centralised invitation of target population, along with effective mass media campaigns.

Acknowledgements and funding

The authors want to thank all screening centres of the organised screening programmes, Institute for Health Informatics and Statistics (administrator of the Czech National Cancer Registry) and public health insurance companies for devoted cooperation in system for information support.

This work was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Ministry of Health Care (grant no. 10650-3).

Práce vznikla za podpory grantu č. 10650-3 GA AV ČR MZ ČR.The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do bi omedicínských časopisů.Assoc. Prof. MUDr. Ladislav Dušek, Ph.D.

Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses

Masaryk University in BrnoFaculty of Medicine and Faculty of Science

Kamenice 126/3

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: dusek@iba.muni.cz

Sources

1. Council recommendation of 2 December 2003 on cancer screening (2003/ 878/ EC). Official J Eur Union 2003; L 327/ 34 : 85 – 89.

2. Schopper D, de Wolf C. How effective are breast cancer screening programmes by mammography? Review of the current evidence. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(11): 1916 – 1923.

3. Olsen AH, Njor SH, Vejborg I et al. Breast cancer mortality in Copenhagen after introduction of mammography screening: cohort study. BMJ 2005; 330(7485): 220.

4. Sarkeala T, Heinävaara S, Anttila A. Organised mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality: a cohort study from Finland. Int J Cancer 2008; 122(3): 614 – 619.

5. Gabe R, Tryggvadóttir L, Sigfússon BF et al. A case ‑ control study to estimate the impact of the Icelandic population‑based mammography screening program on breast cancer death. Acta Radiol 2007; 48(9): 948 – 955.

6. Paci E, Coviello E, Miccinesi G et al. Evaluation of service mammography screening impact in Italy. The contribution of hazard analysis. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44(6): 858 – 865.

7. Otto SJ, Fracheboud J, Looman CW et al. Initiation of population‑based mammography screening in Dutch municipalities and effect on breast ‑ cancer mortality: a systematic review. Lancet 2003; 361(9367): 1411 – 1417.

8. Ascunce EN, Moreno‑Iribas C, Barcos Urtiaga A et al. Changes in breast cancer mortality in Navarre (Spain) after introduction of a screening programme. J Med Screen 2007; 14(1): 14 – 20.

9. SOSSEG. Reduction in breast cancer mortality from the organized service screening with mammography: 1. Further confirmation with extended data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15(1): 45 – 51.

10. SOSSEG. Reduction in breast cancer mortality from the organised service screening with mammography: 2. Validation with alternative analytic methods. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15(1): 52 – 56.

11. Blanks RG, Moss SM, McGahan CE et al. Effect of NHS breast screening programme on mortality from breast cancer in England and Wales, 1990 – 1998: comparison of observed with predicted mortality. BMJ 2000; 321(7262): 665 – 669.

12. Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med 1993; 328(19): 1365 – 1371.

13. Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal ‑ occult‑blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996; 348(9040): 1472 – 1477.

14. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J et al. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal ‑ occult‑blood test. Lancet 1996; 348(9040): 1467 – 1471.

15. Kronborg O, Jørgensen OD, Fenger C et al. Randomized study of biennial screening with a faecal occult blood test: results after nine screening rounds. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004; 39(9): 846 – 851.

16. Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(6): 1541 – 1549.

17. Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH et al. The effect of fecal occult‑blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(22): 1603 – 1607.

18. Guittet L, Bouvier V, Mariotte N et al. Comparison of a guaiac based and an immunochemical faecal occult blood test in screening for colorectal cancer in a general average risk population. Gut 2007; 56(2): 210 – 214.

19. Levi Z, Rozen P, Hazazi R et al. A quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test for colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146(4): 244 – 255.

20. Zheng S, Chen K, Liu X et al. Cluster randomization trial of sequence mass screening for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46(1): 51 – 58.

21. Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF et al. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150(1): 1 – 8.

22. Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V et al. Protection from right ‑ and left ‑ sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy: population‑based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102(2): 89 – 95.

23. Kahi CJ, Imperiale TF, Juliar BE et al. Effect of screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7(7): 770 – 775.

24. Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 1993; 329(27): 1977 – 1981.

25. Ransohoff DF. How much does colonoscopy reduce colon cancer mortality? Ann Intern Med 2009; 150(1): 50 – 52.

26. Brenner H, Haug U, Arndt V et al. Low risk of colorectal cancer and advanced adenomas more than 10 years after negative colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2010; 138(3): 870 – 876.

27. Singh H, Turner D, Xue L et al. Risk of developing colorectal cancer following a negative colonoscopy examination: evidence for a 10‑year interval between colonoscopies. JAMA 2006; 295(20): 2366 – 2373.

28. Brenner H, Chang ‑ Claude J, Seiler CM et al. Does a negative screening colonoscopy ever need to be repeated? Gut 2006; 55(8): 1145 – 1150.

29. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer ‑ Preventive Strategies. Cervix Cancer Screening. Lyon: IARCPress; 2005.

30. Hakama M, Räsänen ‑ Virtanen U. Effect of a mass screening program on the risk of cervical cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1976; 103(5): 512 – 517.

31. Lăără E, Day NE, Hakama M. Trends in mortality from cervical cancer in the Nordic countries: association with organised screening programmes. Lancet 1987; 1(8544): 1247 – 1249.

32. Nieminen P, Kallio M, Anttila A et al. Organised vs. spontaneous Pap ‑ smear screening for cervical cancer: A case ‑ control study. Int J Cancer 1999; 83(1): 55 – 58.

33. Vainio H, Bianchini F. Breast Cancer Screening. Lyon: IARCPress 2002.

34. Karsa L, Anttila A, Ronco G et al. Cancer Screening in the European Union. Luxemburg: European Communities 2008.

35. Dušek L, Mužík J, Kubásek M et al. Epidemiology of Malignant Tumours in the Czech Republic 2007 [cited 2010 22 Sep]. Available from: http:/ / www.svod.cz/ .

36. Svobodník A, Daneš J, Skovajsová M et al. Current Results of the National Breast Cancer Screening Program in the Czech Republic. Klin Onkol 2007; 20 (Suppl 1): 161 – 165.

37. Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. 4th ed. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the EC 2006.

38. Frič P. The use of haemoccult test in the early diagnosis of colerectal cancer – experience from six pilot studies in Czechoslovakia. In: HardcastleJD (ed). Haemoccult screening for the early detection of colorectal cancer. Stuttgart: Schattauer 1986 : 73 – 74.

39. Šachlová M, Novák J. Reflection about the Colorectal Carcinoma Screening Evolution. Klin Onkol 2009; 22(5): 242.

40. Zavoral M, Závada F, Frič P. Český národní program sekundární prevence kolorektálního karcinomu. Čes a Slov Gastroent a Hepatol 2005; 59(1): 7 – 10.

41. Zavoral M, Suchanek S, Zavada F et al. Colorectal cancer screening in Europe. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(47): 5907 – 5915.

42. Lieberman D. A call to action – measuring the quality of colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(24): 2588 – 2589.

43. Rex DK. Quality in colonoscopy: cecal intubation first, then what? Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101(4): 732 – 734.

44. Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(19): 1795 – 1803.

45. Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. 2nd ed. Luxembourg: European Communities 2008.

46. Ferlay J, Shin H, Bray F et al. GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10, 2010 [cited 2010 22 Sep]. Available from: http:/ / globocan.iarc.fr/ .

47. Karim ‑ Kos HE, de Vries E, Soerjomataram I et al. Recent trends of cancer in Europe: a combined approach of incidence, survival and mortality for 17 cancer sites since the 1990s. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44(10): 1345 – 1389.

48. Dušková J, Povýšil C, Juliš I et al. National Cervical Cancer Screening Program from the Pathologists’ point of view. Klin Onkol 2006; 19(1): 33 – 34.

49. Sarkeala T, Anttila A, Forsman H et al. Process indicators from ten centres in the Finnish breast cancer screening programme from 1991 to 2000. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40(14): 2116 – 2125.

50. Lynge E, Olsen AH, Fracheboud J et al. Reporting of performance indicators of mammography screening in Europe. Eur J Cancer Prev 2003; 12(3): 213 – 222.

51. Hofvind S, Geller B, Vacek PM et al. Using the European guidelines to evaluate the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Program. Eur J Epidemiol 2007; 22(7): 447 – 455.

52. Day NE, Williams DR, Khaw KT. Breast cancer screening programmes: the development of a monitoring and evaluation system. Br J Cancer 1989; 59(6): 954 – 958.

53. Bennett RL, Blanks RG, Patnick J et al. Results from the UK NHS Breast Screening Programme 2000 – 2005. J Med Screen 2007; 14(4): 200 – 204.

54. Vejborg I, Olsen AH, Jensen MB et al. Early outcome of mammography screening in Copenhagen 1991 – 1999. J Med Screen 2002; 9(3): 115 – 119.

55. Fracheboud J, Groenewoud JH, Boer R et al. Seventy ‑ five years is an appropriate upper age limit for population‑based mammography screening. Int J Cancer 2006; 118(8): 2020 – 2025.

56. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(9): 627 – 637.

57. Federici A, Giorgi Rossi P, Borgia P et al. The immunochemical faecal occult blood test leads to higher compliance than the guaiac for colorectal cancer screening programmes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Screen 2005; 12(2): 83 – 88.

58. Black ME, Yamada J, Mann V. A systematic literature review of the effectiveness of community‑based strategies to increase cervical cancer screening. Can J Public Health 2002; 93(5): 386 – 393.

59. Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J et al. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(13): 1601 – 1605.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2010 Issue 5-

All articles in this issue

- Diagnostic Pitfalls of HIV‑ Associated Kaposi Sarcoma

- Detection of DNA Hypermethylation as a Potential Biomarker for Prostate Cancer

- Hand‑ Foot Syndrome after Administration of Tyrosinkinase Inhibitors

- The Role of Membrane Transporters in Cellular Resistance of Pancreatic Carcinoma to Gemcitabine

- 18F‑ FDG PET/ CT and 99mTc‑ MIBI Scintigraphy in Evaluation of Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance: Comparison of Methods

- Treatment Results in Patients Treated from 1980 to 2004 for Wilms‘ Tumour in a Single Centre

- A Case of a Patient with a Triple Negative Breast Cancer and Complete Response of Lung, Mediastinal and Skeletal Metastases after Treatment with Paclitaxel and Bevacizumab

- Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the Czech Republic

- Czech National Cancer Screening Programmes in 2010

- Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of a Nasal Cavity – a Rare Tumour

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Diagnostic Pitfalls of HIV‑ Associated Kaposi Sarcoma

- Hand‑ Foot Syndrome after Administration of Tyrosinkinase Inhibitors

- Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of a Nasal Cavity – a Rare Tumour

- 18F‑ FDG PET/ CT and 99mTc‑ MIBI Scintigraphy in Evaluation of Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance: Comparison of Methods

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career