-

Medical journals

- Career

Observations of different patterns of dysplasia in barrett’s esophagus - a first step to harmonize grading

Authors: Michael Vieth 1 *; Elizabeth; Montgomery 2 *; Robert H Riddell 3

Authors‘ workplace: These authors share first authorship having contributed equally to the work *; Institut für Pathologie, Klinikum Bayreuth GmbH, Bayreuth, Germany 1; Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore MD, USA 2; Dept. of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto Ontario, Canada 3

Published in: Čes.-slov. Patol., 52, 2016, No. 3, p. 154-163

Category: Original Article

Overview

We reviewed a set of cases of early neoplasia (low grade / high grade dysplasia / IEN and mucosal carcinoma) to reach better defined criteria for subtypes of dysplasia/differentiation in the columnar lined (Barrett’s) esophagus. We discuss criteria that we categorized for recognizing low and high-grade dysplasia and mucosal carcinoma in patterns of neoplasia that we regarded as intestinal, gastric and mixed.

Keywords:

Barrett – neoplasia – dysplasia – criteria – histomorphology – carcinoma

Evaluating dysplasia (intraepithelial neoplasia), and distinguishing it from the earliest signs of intramucosal carcinoma in the gastrointestinal tract, is problematic due to a combination of both inter-and intraoberserver variations, differences in criteria and terminology, and also because different pathways exist in different organs. Other than those in the large bowel, these have not been well characterized. Barrett’s epithelium is particularly notable in this respect, as it includes intestinal, gastric and mixed pathways, but these various phenotypes have never been fully characterized. Until this occurs, it is impossible to utilize a workable grading system as the criteria cannot be the same for each pathway. In the large bowel this difficulty was apparent in the setting of colitis-associated dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia in 1983 (1) and confirmed in Barrett’s mucosa in subsequent studies in 1988 and 2001 (2,3). Efforts to refine diagnostic criteria (2,4,5) are limited by several factors. Specifically, early neoplastic lesions have tended to be evaluated as a continuum rather than in specific pathways, or combinations of pathways. Different observers have different thresholds for evaluating biopsy features, and likely differ between biopsy and resection specimen, as the context and extent of disease makes it much easier to evaluate in larger specimens. Thus, the threshold to diagnose intramucosal carcinoma is, in general, higher in a biopsy than in a resection specimen especially in Western countries.

It is also apparent that pathologists use different thresholds for defining invasion into the lamina propria (6). This is also an issue that has been of interest in gastric lesions (7-12) but is important in both gastric lesions and in Barrett’s esophagus with advances in both endoluminal imaging (13,14) and endoscopic treatments (15-17).

For all of these reasons, we see an increasing need for harmonization so that outcome studies are internationally interpretable. While endoscopic resection/endoscopic submucosal dissection treatment in BE was not accepted in the USA as readily as it was in Europe, it is now considered the standard of care for Barrett’s-associated early neoplasia (high-grade dysplasia and early invasive carcinomas) in the USA (18). For low grade dysplasia, many observers argue that since low grade dysplasia can be found at the edge of higher grade lesions, it is also reasonable to manage low-grade dysplasia by endoscopic resection if a lesion is endoscopically visible (19). Previously esophagectomy was considered appropriate treatment for high-grade dysplasia.

Since most mucosal neoplasms are associated with a favorable outcome (15-17), a large number of cases assessed similarly will be required to determine which prognostic features are valid regarding recurrence, but our ability to compare studies is hampered by lack of any classification system of lesions. The fact that neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus is relatively uncommon will likely be even more important when applied to early submucosal carcinomas. Until there is more precise understanding of pathways with use of harmonized terminology, it will be impossible to correlate individual features with outcome, as has been done in other organ systems with great success (20,21). There are no comprehensive detailed descriptions that allow differentiation between different epithelial subtypes or the grades of dysplasia/intraepithelial neoplasia and carcinomas occurring within them. Those that do exist are described in relative terms - more of this and less of that. Although this is to a large extent inevitable whenever spectra of changes occur, it does make grading far more problematic.

We reviewed a set of slides of early neoplasia (low grade/high grade dysplasia/ IEN and mucosal carcinoma) in the columnar lined (Barrett’s) esophagus in an attempt to better define the issues that have resulted in this relative chaos, and, if possible, to propose a template upon which outcome studies can be based. We did not focus on whether there was background intestinal metaplasia (19,22) since, in daily practice, it is irrelevant to this issue, but did include lesions of the distal esophagus and cardia/esophago-gastric junction, as these must be dealt with as a continuum since both are amenable to endoscopic treatment. Nor did we concentrate on reactive changes.

Our reasoning for this review was that published criteria have been limited in both recognizing variant dysplasia patterns (23-29) that are now better defined than in the time of early inter-observer studies, and in using different systems to classify early (mucosal) invasion. Furthermore, now that endoscopic treatment is the treatment of choice, diagnosing high grade dysplasia and early carcinoma no longer equates with anticipating an esophagectomy. Pathologists have therefore become less reluctant to diagnose them (sometimes to the point of overdiagnosis (30)). Indeed endoscopic management already extends to low grade dysplasia in some centers, so the threshold for endoscopic intervention is also changing, and its effectiveness will need to be assessed prospectively. There are several published schemes to address depth of invasion of intramucosal lesions and submucosal carcinomas (5,31,32). These are especially pertinent in reviewing endoscopic mucosal resection and submucosal dissections (31,33-36). However, assessment of submucosal disease was not a thrust or intended endpoint for our review.

Using a highly selected series of slides to reflect the diversity of changes found in dysplastic Barrett’s mucosa utilizing both biopsies or endoscopic resections, the aim of this study was therefore to define the types of epithelium in which dysplasia arose, and to examine the criteria we use particularly in separating LGD from HGD or mucosal carcinoma, as these are currently the areas on which endoscopic therapy is based. Despite the demonstrated poor reproducibility in separating HGD from intramucosal carcinoma in biopsies (6,37,38), pathologists do seem to attempt to include this distinction in their reports, the implication being that intramucosal carcinoma is one feature that is more likely to be associated with deeper invasion, and therefore an increased chance of an unsuccessful complete endoscopic excision. We therefore reviewed our criteria used in making this distinction when the opportunity arose.

CASES REVIEWED

We reviewed biopsies or EMRs from 100 patients compiled from our respective institutions. Cases were drawn from both institutional archives and from those referred for consultation, so are not representative of any population. We classified each case for the types of epithelium in which dysplasia arose as a construct to uncover issues in grading. From analyzing our routine archives in Bayreuth we know that almost 5% of cases with Barrett’s neoplasia show mixtures with or pure gastric differentiations whereas typically intestinal differentiation is encountered in Barrett’s neoplasia. In Baltimore and Toronto, with a large consultation practice such lesions account for about 10% of Barrett neoplasia. It seems that those showing gastric differentiations with or without an intestinal component may account for diagnostic difficulties in routine practice. Using mucin antibodies routinely would probably lead to detection of larger proportion of gastric differentiation but we would not advocate this practice at the present time. For phenotypic classification by expression of mucins, see table 1.

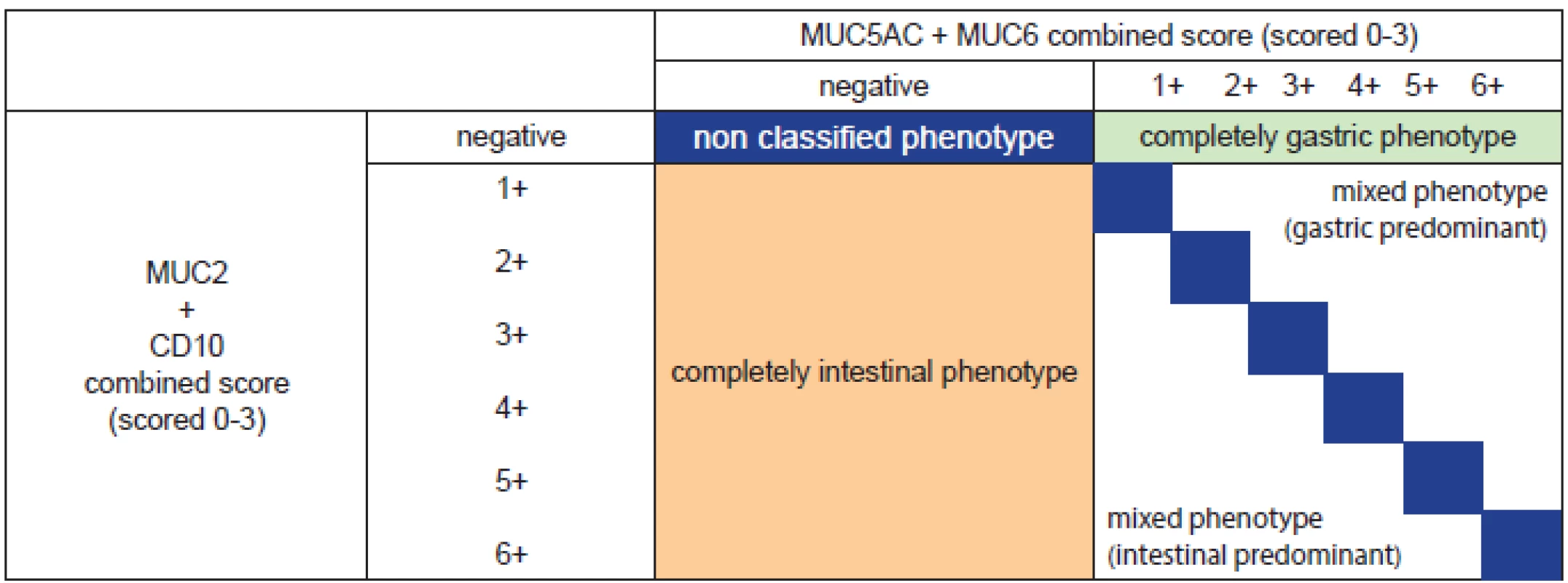

1. Phenotypic classification by expression of mucins (MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2) and CD10 (modified from (53). All markers are scored as following: negative = 0-4 % reactivity, 1+ = 5-30 %, 2+ = 31-60 %, 3+ >60 %. Some tumors have a phenotype that is either entirely gastric (green box) or enterily intestinal (orange box), while a small proportion have no identifiable (nonclassified) phenotype (large blue box). However, many tumors express both gastric and intestinal phenotypes (lower right) and these may be either predominantely intestinal (below and to the left of the blue boxes=, or predomintantely gastric (above and right of the blue boxes). The blue boxes themselves indicate tumors that express roughly equal quantities of both intestinal and gastric markers, varying from minimal (grade 1 of each) to grade 6 (abundant expression of both). Noteworthy that with degree of neoplasia entirely and predominantely intestinal phenotypes become lesser and entirely gastric differentiated tumors are seen more often together with a marked proportion of mixed phenotypes predominantely gastric (53). In practice, the routine use of immunohistochemistry outside from studies is not recommended.

Variants of dysplasia

We attempted to define the types of differentiation that neoplasia displayed and our categories are based on our collective experience rather than outcome studies. This involved assessing differentiating cells within the dysplasia such as goblet cells, foveolar cells, the presence of both, the presence of pyloric gland nuclei and cytoplasm, and sometimes the presence of specialized gastric mucosa (parietal and chief cells = oxyntic mucosa). Combined (mixed) forms of neoplasia were also noted.

Grading dysplasia in Barrett’s Mucosa

For the purposes of this discussion, we divided columnar dysplasia into the subgroups found from the preceding section, with examples of each. Nuclear features included those showing intestinal type stratified nuclei akin to those in a colorectal adenoma, those with a monolayer of small hyperchromatic nuclei described with various terms (25,28,29,39), examples that exhibit features analagous to those in both foveolar and pyloric gland adenoma (40,41), and also fundic gland dysplasia, cases lacking surface involvement (23,24), and cases showing surface extension remote from the main lesion. For each of these types of lesion, we attempted to define criteria for low and high-grade dysplasia, and criteria for invasion into the lamina propria (or beyond if this was feasible - intramucosal carcinoma involving invasion into the lamina propria or into or through the duplicated muscularis mucosae).

RESULTS

We identified what appeared to be areas of epithelial neoplasia showing differentiation along one type of epithelium, and those that appeared to be admixed with more than one type of neoplastic mucosa. As this series of cases was specifically chosen to illustrate unusual pathways and did not represent consecutive cases, no precise attempt is made to provide the proportion of cases showing those changes, as such figures are meaningless in this context.

Evaluation was based on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining but for illustrative purposes below we have included images showing MUC immunostaining (42) from other cases. However MUC or other histochemical or immunochemical methods were not routinely used to separate these, there currently being no reason to do this if differentiation can be identified on an H&E section. Whether this is correct, or of any clinical or prognostic significance, remains to be determined. Nevertheless, given the rarity of some of the various types of differentiation, many will be far more comfortable using MUC immunostaining to confirm their initial impression. It may be of value particularly in separating tangential sectioning pyloric gland dysplasia from low grade foveolar dysplasia, as nuclear features can be quite similar.

Pure epithelial subtypes

These included

- a) dysplasia arising in “complete” intestinal metaplasia (i.e. no foveolar type mucous secreting cells and containing absorptive type cells and often Paneth and/or Kulchitsky cells in addition)

- b) gastric types of dysplasia that included foveolar dysplasia, pyloric gland dysplasia (similar to changes found in pyloric gland adenoma), and oxyntic dysplasia. We did not find dysplasia involving pancreatic metaplasia/heterotopia or multilayered epithelium in this series of cases, although it is not unreasonable to propose that at least some of the gastric variants of dysplasia could have arisen from pancreatic metaplasia in particular. However, dysplasias were found involving esophageal ducts and glands. These appeared to be secondarily involved from more widespread surface changes so were not interpreted as arising specifically from those structures. As in melanoma, such secondary involvements were not taken as invasion per se.

Mixed types of dysplasia

These were combinations of either intestinal and gastric dysplasia or multiple types of gastric dysplasia as defined above. One pattern is that occurring with the combined presence of intestinal (goblet cells) and surface gastric foveolar mucinous epithelium, which historically was called “incomplete” intestinal metaplasia. As this is the most common pattern of goblet cells in non-dysplastic mucosa, and is therefore the type most frequently used to make a diagnosis of BE in those countries in which goblet cells are still an intrinsic part of the diagnosis of BE, (especially North America but also parts of Europe) this was not surprising. It is also well recognized that higher grades of dysplasia may differentiate towards intestinal type mucosa even when the less dysplastic lesion did not have these changes, akin to many mixed type gastric carcinomas.

Combinations of gastric types of dysplasia were also encountered, by far the most common being those associated with foveolar dysplasia and those with pyloric gland dysplasia.

GRADING OF DYSPLASIA

Throughout we have accepted that crypt (pit) dysplasia (23, 24) can be encountered if the criteria for low or high grade dysplasia are fulfilled (other than surface involvement), and that surface maturation does not preclude this diagnosis although additional care does need to be taken to ensure that lesions are not reactive.

1. Conventional Intestinal-Type Dysplasia

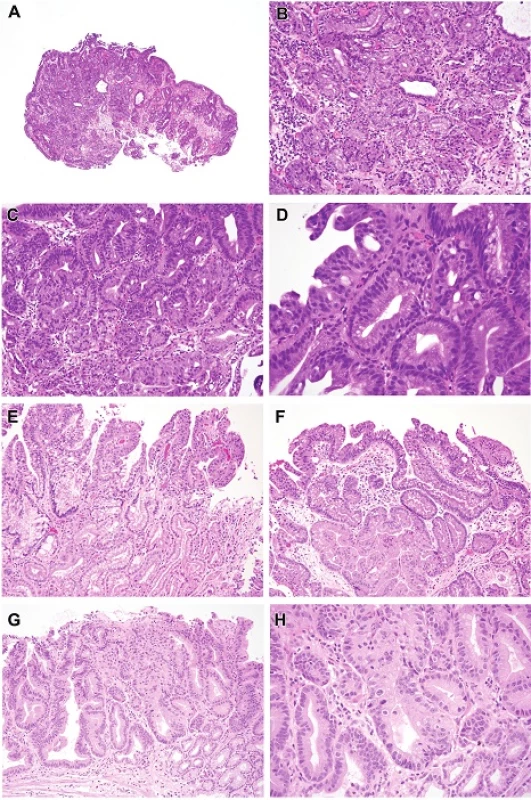

A. Low-Grade Dysplasia (Figures 1A-D)

Low-grade Dysplasia Architectural features

- Glandular architectural features that are similar to those encountered in non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus with lamina propria between glands.

Low-grade Dysplasia Nuclear features

- Stratified, hyperchromatic nuclei that reach the surface

- No round nuclei

- Preserved nuclear polarity

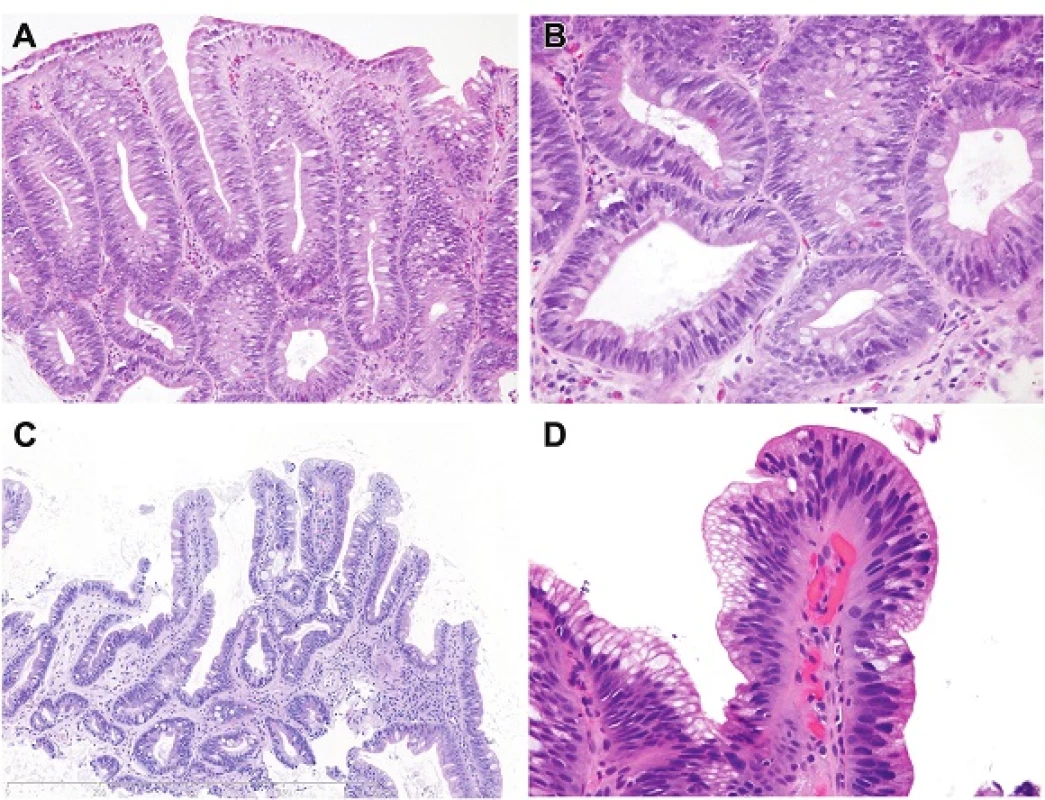

1. A. Intestinal type dysplasia. In rare examples, intestinal type low-grade dysplasia resembles a colonic tubular adenoma, as in this case, sometimes even interpreted as adenomatous changes. The nuclei are “pencillate”/elongated, hyperchromatic and are all oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane. H&E (200x). B. This is a detail of image A. Note that the nuclei are stratified and that goblet cells are easy to identify. There are Paneth cells in the upper left part of the field. H&E (400x). C. This example of low-grade dysplasia with intestinal differentiation shows a typical density of glands and the pits form tubules the same size as those in nondysplastic columnar mucosa. Note that, although goblet cells are readily identified, there are gastric foveolar cells admixed such that it can be viewed as a mixed type of dysplasia (“incomplete intestinal”). H&E (100x). D. Intestinal type low-grade dysplasia. This is the surface. Note in this case, there are some surface foveolar cells such that the dysplasia is mixed in the manner of incomplete intestinal metaplasia. Note that the nuclei are hyperchromatic at the surface but retain their polarity but show an abrupt transition to the adjacent non-neoplastic epithelium. H&E (400x).

B. High-grade dysplasia (Figures 2A-C)

High-Grade Dysplasia Architectural Features

- Features that are not altered from that which can be seen in non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (and a key feature when considering mucosal carcinoma)

High-Grade Dysplasia Nuclear Features

- Stratified hyperchromatic nuclei that reach the surface of the epithelium

- Rounded hyperchromatic nuclei

- Loss of nuclear polarity

2. Intestinal type high-grade dysplasia. Goblet cells are easily seen in this example, which shows stratified nuclei reaching the luminal surface. H&E (200x). B. There is also a transition to rounded more pleomorphic nuclei and loss of nuclear polarity (bottom left). H&E (400x). C. This image shows not only loss of nuclear polarity of round pleomorphic nuclei and a goblet cell, but there is neuroendocrine differentiation (Kulchitsky type cells) in the center of the field, a feature that probably informs the capacity of Barrett-associated columnar epithelial dysplasia to give rise to neuroendocrine carcinomas, as seen also in the colon. It is noteworthy that Barrett’s epithelium often has a greater density of neuroendocrine cells than stomach or colon. H&E (400x). D. Mucosal carcinoma. Note that the atypical tubules extend laterally. Some contain luminal necrosis (those in the inner muscularis mucosae). H&E (40x). E. In this example of intramucosal carcinoma, tiny tubules proliferate between normally sized tubules and some of the glands show lateral expansion H&E (100x). F. In this example of intramucosal carcinoma, the disturbed gland architecture is the key to separating the findings from those of high-grade dysplasia. There is no desmoplasia. H&E (100x).

C. Features Indicative of Lamina Propria Invasion (Figures 2D-2F)

- Nuclear features of low or high grade dysplasia as outlined above with any of the following:

- Single or groups of cells between pre-existing glands

- Intertubular fusion of glands / lateral expansion (lateral growth of glands)

- Architectural cribriforming beyond that seen in non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus

2. So-called Gastric Type or Foveolar Dysplasia

There are two types of dysplasia that can be termed gastric type (and these differ somewhat from pyloric/cardiac type below), one of these akin to the pure foveolar type seen on the surface of gastric fundic gland polyps or gastric adenomas that arise in uninflamed gastric mucosa or in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (43-46) and a second type that has been described as “non-adenomatous”(29) to underscore the arrangement of nuclei in a monolayer in contrast to the pattern in overtly intestinalized Barrett-associated dysplasia. We did not identify a low-grade form of this latter type of dysplasia and believe some lesions described as a low-grade form instead show pyloric gland type differentiation (see section 3, below).

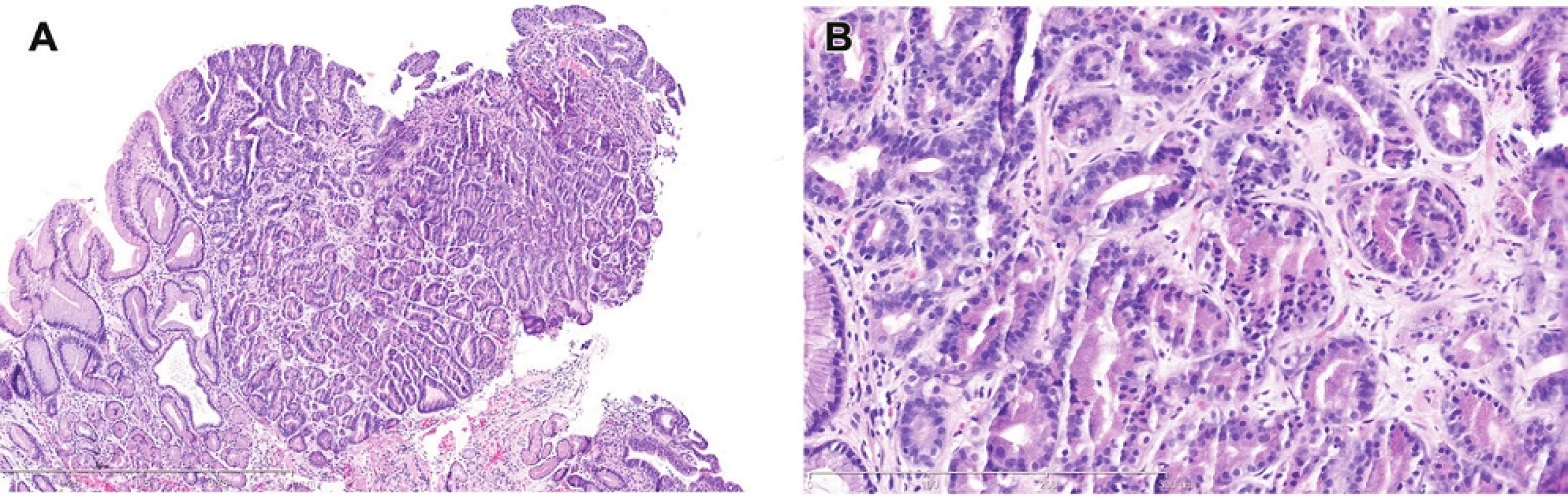

A. Low-grade Dysplasia, Gastric Foveolar Type (Figures 3A-3B)

Low-grade Dysplasia, Gastric Foveolar Type, Architectural Features

- Similar to those seen in non-dysplastic columnar mucosa with changes seen on the surface

Low-grade Dysplasia, Gastric Foveolar Type, Cytologic Features

- Slightly stratified, oval hyperchromatic nuclei

- Abundant apical mucin cap of neutral mucin in cells

- No loss of nuclear polarity

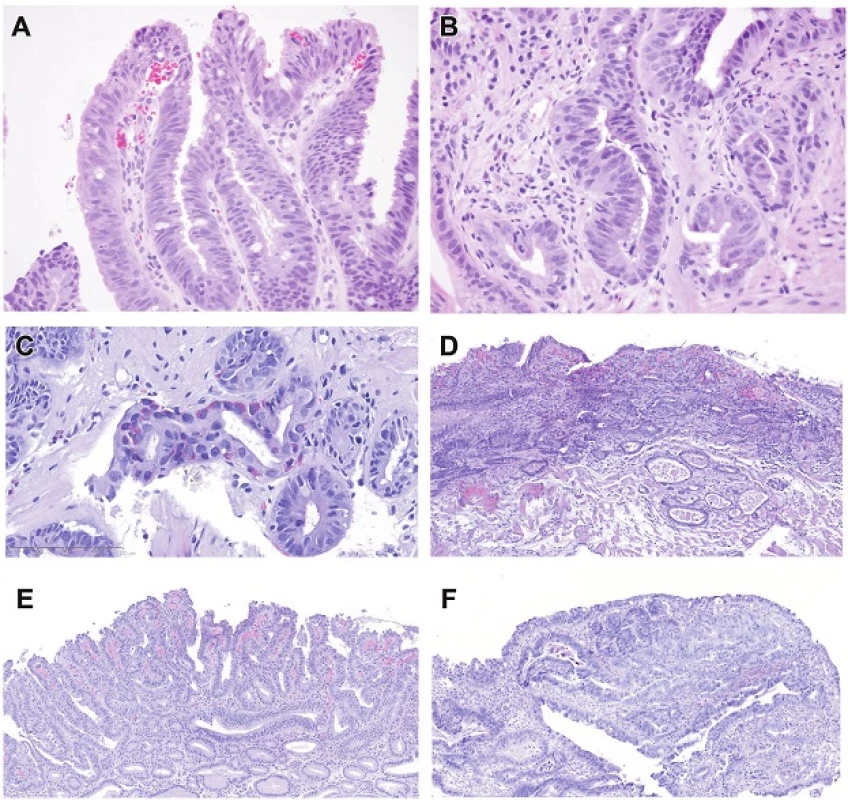

3. Foveolar type low-grade dysplasia. In this example the surface nuclei are hyperchromatic and each cell contains abundant neutral mucin in the manner of gastric foveolar cells. Lesions such as this are seldom encountered in our practice and most lesions with foveolar differentiation are classified as high-grade dysplasia.H&E (100x). B. Higher magnification of the lesion seen in 3A, showing the nuclear detail H&E (200x). C. This example of foveolar type high-grade dysplasia shows surface loss of nuclear polarity and foveolar type mucin. It was encountered at the surface of a carcinoma. H&E (400x). D. Detail shows closely packed tubules with a monolayer of basal hyperchromatic nuclei with loss of polarity (loss reproducibility between adjacent nuclei and loss of relationship to the basement membrane). Some observers regard this type as “non-adenomatous” rather than foveolar since the cells have mucin characteristics of intestinalization but lack stratified nuclei. Notice that more stratified nuclei are present at the left part of the field. A small amount of foveolar mucin is seen in the cells at the lower right of the field. This type of differentiation is similar to that encountered in pyloric/cardiac differentiation but features more hyperchromatic nuclei.H&E (200x). E. Foveolar type intramucosal carcinoma. Note the small round glands (high-grade dysplasia) deeper down and the surface foveolar epithelium that is focally maturing so resembles low grade foveolar dysplasia. However, the deep glands at the right are angulated with a disturbed complex architecture and beginning to invade the lamina propria. There is no desmoplastic response. H&E (100x). F. Foveolar type intramucosal carcinoma. This is high magnification of the area in question in Figure 3E. The nuclei have also acquired more prominent nucleoli. H&E (200x)

B. High-grade dysplasia, Gastric Foveolar and Nonstratified Type (Figures 3C-3D)

High-grade Dysplasia, Gastric Foveolar Type, Architectural Features

- Glands more crowded and smaller than those seen in normal columnar-lined esophagus

High-grade Dysplasia, Gastric Foveolar Type, Cytologic Features

- A cytoplasmic foveolar mucin cap may be seen accompanied by rounded extremely hyperchromatic nuclei

- Small tubules with a monolayer (non-stratified/”non-adenomatous”) hyperchromatic nuclei showing open chromatin with dense peripheral condensation and inconspicuous nucleoli

- Loss of nuclear polarity

C. Features Indicative of Lamina Propria Invasion (Figures 3E-3F)

- Nuclear features of low or high grade dysplasia as outlined above with any of the following:

- Single or groups of cells between pre-existing glands

- Intertubular fusion of glands/ lateral expansion

- Architectural cribriforming beyond that seen in non-dysplastic BE

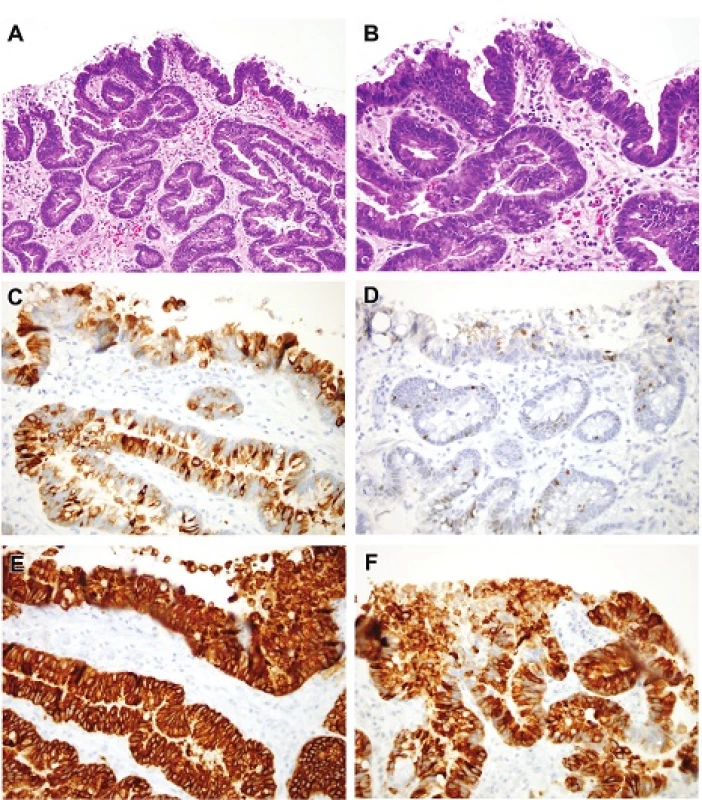

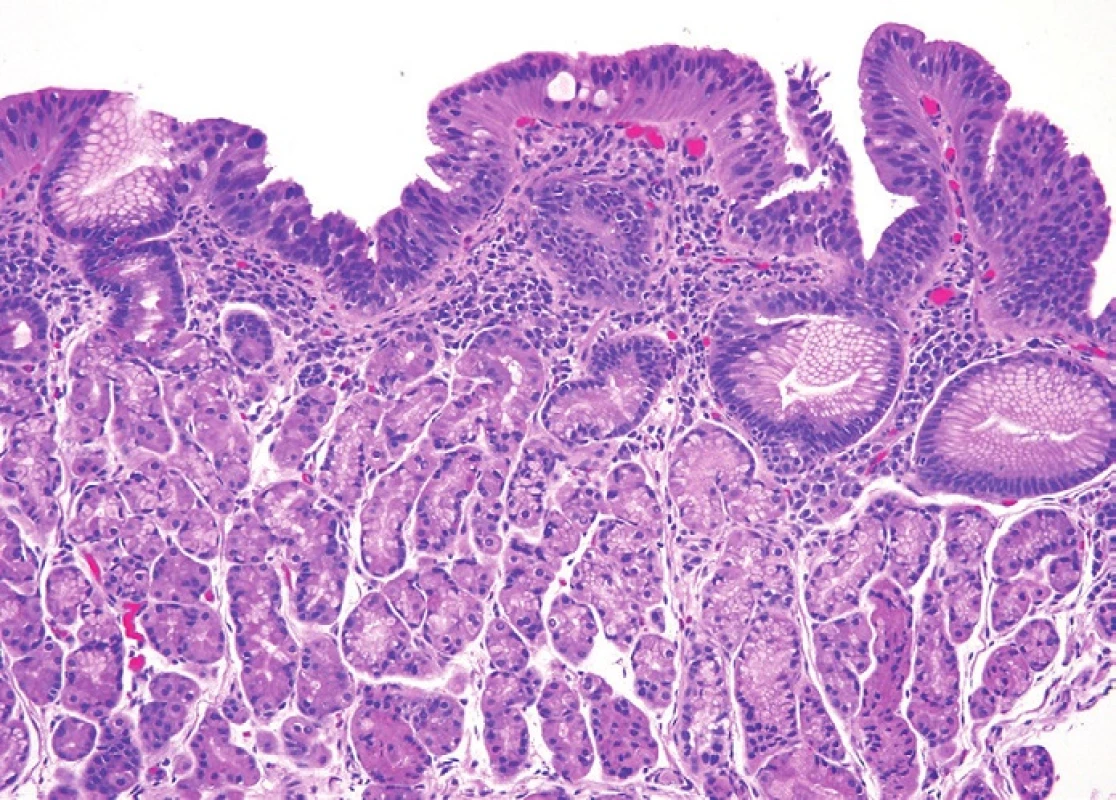

3. Dysplasia with Pyloric Gland/Cardiac Gland Differentiation

(Figures 4A-4H)

A. Low-Grade Pyloric/Cardiac Dysplasia

Low-grade Dysplasia, Pyloric Gland/Cardiac Gland Differentiation, Architectural Features

- Glands more crowded, more densely packed and often smaller than those seen in normal columnar-lined esophagus

Low-grade Dysplasia, Pyloric Gland/Cardiac Gland Differentiation, Cytologic Features

- Round nuclei (not hyperchromatic)

- Minimal elevation of nuclei from base of cell into cytoplasm

- Pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm with ground glass features (rather than an apical mucin cap or goblet cell differentiation) or residual pyloric/cardiac type mucus

- Cuboidal epithelial features

- Densely packed glands with uniform pattern (cysts can be observed in some cases)

(Immunohistochemistry: Muc6 positive throughout most of the thickness of the mucosa although the surface may not stain, Muc5AC stains the surface layer for in most cases)

B. High-Grade Pyloric/Cardiac Dysplasia

High-grade Dysplasia, Pyloric Gland/Cardiac Gland Differentiation, Architectural Features

- Glands more crowded and smaller than those seen in normal columnar-lined esophagus

High-grade Dysplasia, Pyloric Gland/Cardiac Gland Differentiation, Cytologic Features

- Criteria as in LGD but with loss of polarity of the nuclei, which may also have hyperchromasia and pleomorphism (such areas can be highlighted with Ki67 stain). The hyperchromasia is usually less than that encountered in the gastric-type pattern outlined above.

C. Features Indicative of Lamina Propria Invasion

- Seen above on LGD/HGD plus clear lamina propria invasion or intertubular fusion of glands/ lateral expansion.

4. A. Pyloric/cardiac gland dysplasia. This lesion presented as a nodule. The closely packed tubules with focal pit dilatation and relatively pale appearance are features of pyloric gland differentiation. H&E (40x). B. This is an example of lowgrade pyloric dysplasia, showing closely packed tubules with “ground glass” cytoplasm rather than foveolar type neutral mucin, and also have small round uniform basal nuclei. H&E (100x). C. High-grade dysplasia. The nuclei are less hyperchromatic than those in intestinal and foveolar type dysplasia. In this example, they have become large and have become stratified at the top of the field with focal cribriform pattern (middle right edge of photograph). H&E (200x). D. Detail shows a gland in the center with low-grade features but to the left the features are those of high-grade dysplasia with pyloric differentiation. Nucleoli are visible left and bottom.H&E (400x). E. The lower part of the field shows low-grade pyloric dysplasia whereas the top shows high-grade features with more pleomorphic nuclei that lose polarity. H&E (100x). F. Pyloric/cardiac gland dysplasia intramucosal carcinoma. This example show a few low-grade glands and the right, high-grade dysplastic changes on the surface and sufficiently complex cribriform architecture in the center to diagnose intramucosal carcinoma. H&E (100x). G. Pyloric/cardiac gland dysplasia, intramucosal carcinoma. The cribriform zone in the center has effaced the lamina propria.H&E (100x) H. This is a detail of the zone in question from Figure 4G. The gland in the center shows complex crypt budding, a feature of early invasion.H&E (200x).

4. Lesions with chief cell differentiation

We have only encountered rare such lesions in the tubular esophagus and they are also rare in the stomach (47,48). An example is shown in Figures 5A-5B.

5. A. Dysplasia with chief cell differentiation. This unusual lesion has features of gastric lesions believed to have oxyntic or chief cell differentiation with deep eosinophilic cytoplasm and small round basal nuclei. Note, however, that the surface has stratified nuclei like those in intestinal type dysplasia.H&E (40x). B. Dysplasia with chief cell differentiation. Note the angulated tubules, many containing cells with grey cytoplasm like that found in the chief cells of oxyntic mucosa. H&E (200x).

5. Any of the above types of differentiation can be mixed

Pure intestinal dysplasia is probably less common than dysplasia in incomplete intestinal metaplasia in which dysplastic goblet cells are typically admixed with foveolar differentiation (akin to the differentiation see in non-dysplastic incomplete intestinal metaplasia), and also similar in many respects to the gastric differentiation can be encountered in colorectal dysplastic polyps, usually of the serrated variety.

However, many lesions display differentiation along many of the above noted lines of differentiation, an impression confirmed by mucin core protein labeling studies (42). Examples of dysplastic lesions showing several lines of differentiation are shown in Figures 6A-6F.

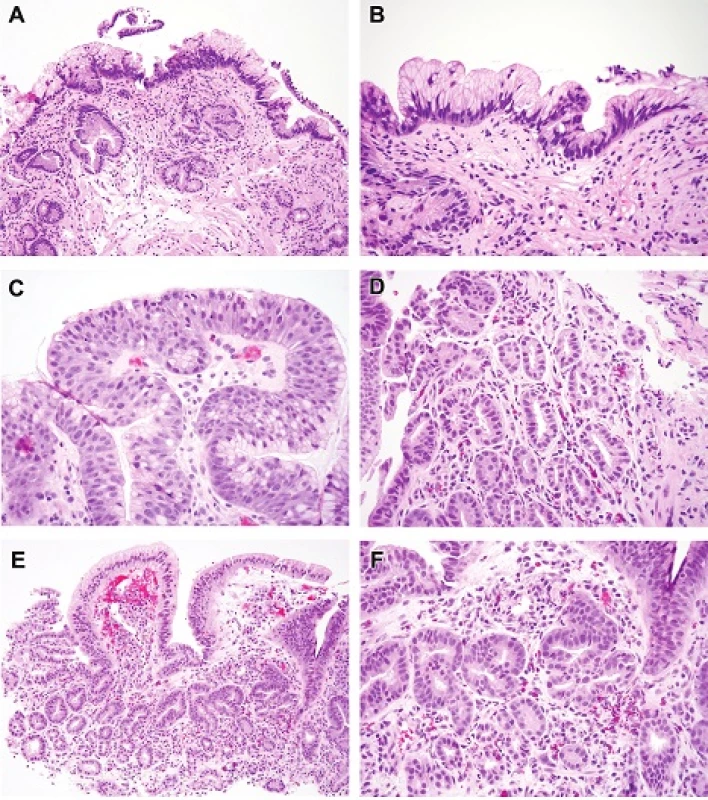

6. A. Dysplasia with mixed differentiation. This tangentially embedded biopsy shows high-grade dysplasia with a host of types of differentiation. At this magnification there is a suggestion of goblet cells as well as of foveolar cells. Angulated glands are not a necessarily a sign of invasion in this tangential example. H&E (100x). B. It is easy to detect loss of nuclear polarity in this example of high-grade dysplasia. H&E (200x). C. This is a MUC2 (same lesion as that seen in Figures 6A and 6B) highlighting abundant goblet cells. MUC2 (200x). D. This is a CDX2 (same lesion as that seen in Figures 6A and 6B) showing occasional immunoreactive nuclei. CDX2 (200x). E. This is a MUC5 that highlights foveolar mucin (same lesion as that seen in Figures 6A and 6B). MUC5AC (200x). F. This is a MUC6 that highlights pyloric gland mucin (same lesion as that seen in Figures 6A and 6B). MUC6 (200x).

6. Lack of Pit involvement - Extension of Dysplasia Along Surfaces Away From the Main Focus

Surface spread can involve any subtype of dysplasia, and most commonly has features of low-grade intestinal type dysplasia with retained nuclear polarity. The underlying pits lack dysplasia, and there is often a junction with them. This pattern is difficult to grade but is typically a marker for higher –grades of neoplasia in adjoining tissue that may or may not have been sampled (Figure 7). A similar pattern can be seen in large bowel adenomas.

7. Lateral (surface) spread over the columnar epithelial surface. In this image, the surface shows dysplastic epithelium with loss of nuclear polarity and nuclear rounding that characterize high-grade intestinal type dysplasia but the lesion sits atop oxyntic mucosa. Adjoining biopsies showed more classic highgrade dysplasia. Such lesions are often seen at the edge of invasive carcinomas that spread into the cardia region. H&E (100x).

7. Serrated Pattern of Dysplasia

Since nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus can display features that resemble a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (Figure 8), it would seem reasonable that a serrated pathway to neoplasia should exist in the esophagus. Such serrations can be found in intestinal, foveolar, and pyloro-cardia type mucosa whether dysplastic or non-dysplastic, so is seems to be more a complicating pattern rather than a unique and specific subtype; indeed flat small bowel mucosa is serrated so may reflect reversion to a very basic or fundamental epithelial pattern of differentiation.

8. This example of nondysplastic Barrett mucosa shows features similar to those seen in serrated colorectal polyps, especially the microvesicular variant. H&E (100x).

The morphological criteria are therefore less precisely defined (27) other than appearing serrated. As Barrett’s neoplasia often shows a mosaic pattern of various differentiations, it can be extremely difficult to precisely identify all of these components. It has been suggested that foveolar (29) and serrated features (published in abstract form; (49)) convey additional risk compared to classic intestinal dysplasia but the data remain incomplete. An illustrated case (27) believed to have features akin to traditional serrated adenoma lacked the ectopic crypt foci that characterize traditional serrated adenoma(50).

Based on our review, any of the forms of dysplasia noted above can show foci with serrations (Figures 9A-9C). Lesions akin to traditional serrated adenomas would be expected to show features of classical intestinal dysplasia with palisading nuclei. Such lesions would be regarded as low grade dysplasia. Defining lesions akin to sessile serrated adenoma/polyps is virtually impossible since such lesions are defined by architecture. We have seen rare esophageal biopsies with serrated features that appear to be dysplastic or early carcinomas (Figures 9D-9F) but are unable to offer criteria for grading them.

Future studies need to show the clinical significance of such components in Barrett’s neoplasia.

9. A. This “nonadenomatous” dysplasia contains glands with serrated contours, as do [H&E (100x)] (B) intestinal and [H&E (100x)] (C) pyloric/cardiac dysplasia in some instances. We have encountered a singular case that would appear to show [H&E (100x)] (D) [H&E (40x)], (E) [H&E (200x)] dysplasia and carcinoma (F) with a serrated appearance [H&E (200x)]. ![A. This “nonadenomatous” dysplasia contains glands with serrated contours, as do [H&E (100x)] (B) intestinal and [H&E (100x)] (C) pyloric/cardiac dysplasia in some instances. We have encountered a singular case that would appear to show [H&E (100x)] (D) [H&E (40x)], (E) [H&E (200x)] dysplasia and carcinoma (F) with a serrated appearance [H&E (200x)].](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/3aba788ded9c8041857fda96308e8c09.jpg)

DISCUSSION

As endoscopic analysis and treatment of columnar esophageal lesions progresses, we hope to provide more uniform assessment of early lesions in our patients. Even in the US, where endoscopic treatment for high-grade dysplasia has been accepted more slowly than in the rest of the world (51), strides have been made in demonstrating that it is as effective as esophagectomy and that most HGDs and intramucosal carcinomas are amenable to endoscopic treatment. Further, many observers believe that persistent low-grade dysplasia should also be managed by some sort of mucosal ablation (19). When patients fail to benefit from (even repeated) radiofrequency ablation (16,17), other modalities can be offered without resorting to esophagectomy (52). As such, if pathologists can recognize additional patterns of low grade dysplasia in routine biopsies, we have a great opportunity to ensure that patients undergo ablation with the goal to reduce the burden of esophageal adenocarcinoma. As such, we have offered examples of dysplasia showing patterns of differentiation that have not been traditionally emphasized in Barrett’s esophagus, but that are present in some biopsies from columnar lined esophagi. Noteworthy that gastroenterological guidelines of Barrett’s start to implement histological criteria as well (54).

We realize that the criteria we have offered are not evidence based but rather a summary of our collective experience and hope others will be able to use them as a framework in prospective studies. They are based on our observation of consultation cases and the difficulties posed by variant patterns and we intend this as a template for future studies and refinements.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Correspondence address:

Dr. Elizabeth A Montgomery

Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Weinberg 2242, 401 N Broadway

Baltimore MD 21231, USA

tel: 410-614-2308

e-mail: emontgom@jhmi.edu

Sources

1. Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF, et al. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum Pathol 1983; 14(11): 931-968.

2. Montgomery E, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett esophagus: a reaffirmation. Hum Pathol 2001; 32(4): 368-378.

3. Reid BJ, Haggitt RC, Rubin CE, et al. Observer variation in the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Hum Pathol 1988; 19(2): 166-178.

4. Odze RD. Diagnosis and grading of dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. J Clin Pathol 2006; 59(10): 1029-1038.

5. Vieth M, Stolte M. Pathology of early upper GI cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005; 19(6): 857-869.

6. Downs-Kelly E, Mendelin JE, Bennett AE, et al. Poor interobserver agreement in the distinction of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in pretreatment Barrett’s esophagus biopsies. AmJ Gastroenterol 2008; 103(9): 2333-2340; quiz 2341.

7. Lauwers GY, Shimizu M, Correa P, et al. Evaluation of gastric biopsies for neoplasia: differences between Japanese and Western pathologists. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23(5): 511-518.

8. Sakurai U, Lauwers GY, Vieth M, et al. Gastric high-grade dysplasia can be associated with submucosal invasion: evaluation of its prevalence in a series of 121 endoscopically resected specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38(11): 1545-1550.

9. Schlemper RJ, Itabashi M, Kato Y, et al. Differences in diagnostic criteria for gastric carcinoma between Japanese and western pathologists. Lancet 1997; 349(9067): 1725-1729.

10. Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, et al. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 2000; 47(2): 251-255.

11. Vieth M, Riddell RH, Montgomery EA. High-grade dysplasia versus carcinoma: east is east and west is west, but does it need to be that way? Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38(11): 1453-1456.

12. Watanabe H, Jass J, Sobin L, eds. Histologic Typing of Oesophageal and Gastric Tumours, page 20. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990.

13. Canto MI, Anandasabapathy S, Brugge W, et al. In vivo endomicroscopy improves detection of Barrett’s esophagus-related neoplasia: a multicenter international randomized controlled trial (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79(2): 211-221.

14. Dunbar KB, Canto MI. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and endoscopically inapparent Barrett’s neoplasia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled, crossover trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72(3): 668.

15. Manner H, Pech O, Heldmann Y, et al. The frequency of lymph node metastasis in early-stage adenocarcinoma of the esophagus with incipient submucosal invasion (pT1b sm1) depending on histological risk patterns. Surgical endoscopy 2015; 29(7): 1888-1896.

16. Pech O, May A, Manner H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for patients with mucosal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology 2014; 146(3): 652-660.

17. Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med 2009; 360(22): 2277-2288.

18. American Gastroenterological Association, Spechler SJ, Sharma P, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011; 140(3): 1084-1091.

19. Bennett C, Moayyedi P, Corley DA, et al. BOB CAT: a large-scale review and delphi consensus for management of Barrett’s esophagus with no dysplasia, indefinite for, or low-grade dysplasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(6): 662-682.

20. Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr., Amin MB, et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. The Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29(9): 1228-1242.

21. Stoler MH. New Bethesda terminology and evidence-based management guidelines for cervical cytology findings. JAMA 2002; 287(16): 2140-2141.

22. Riddell RH, Odze RD. Definition of Barrett’s esophagus: time for a rethink--is intestinal metaplasia dead? Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104(10): 2588-2594.

23. Coco DP, Goldblum JR, Hornick JL, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of crypt dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35(1): 45-54.

24. Lomo LC, Blount PL, Sanchez CA, et al. Crypt dysplasia with surface maturation: a clinical, pathologic, and molecular study of a Barrett’s esophagus cohort. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30(4): 423-435.

25. Mahajan D, Bennett AE, Liu X, et al. Grading of gastric foveolar-type dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Mod Pathol 2010; 23(1): 1-11.

26. Naini BV, Chak A, Ali MA, et al. Barrett’s oesophagus diagnostic criteria: endoscopy and histology. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2015; 29(1): 77-96.

27. Odze RD. What the gastroenterologist needs to know about the histology of Barrett’s esophagus. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2011; 27(4): 389-396.

28. Patil DT, Bennett AE, Mahajan D, et al. Distinguishing Barrett gastric foveolar dysplasia from reactive cardiac mucosa in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Hum Pathol 2013; 44(6): 1146-1153.

29. Rucker-Schmidt RL, Sanchez CA, Blount PL, et al. Nonadenomatous dysplasia in barrett esophagus: a clinical, pathologic, and DNA content flow cytometric study. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33(6): 886-893.

30. Sangle NA, Taylor SL, Emond MJ, et al. Overdiagnosis of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a multicenter, international study. Mod Pathol 2015; 28(6): 758-765.

31. Kaneshiro DK, Post JC, Rybicki L, et al. Clinical significance of the duplicated muscularis mucosae in Barrett esophagus-related superficial adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35(5): 697-700.

32. Westerterp M, Koppert LB, Buskens CJ, et al. Outcome of surgical treatment for early adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or gastro-esophageal junction. Virchows Arch 2005; 446(5): 497-504.

33. Abraham SC, Krasinskas AM, Correa AM, et al. Duplication of the muscularis mucosae in Barrett esophagus: an underrecognized feature and its implication for staging of adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31(11): 1719-1725.

34. Estrella JS, Hofstetter WL, Correa AM, et al. Duplicated muscularis mucosae invasion has similar risk of lymph node metastasis and recurrence-free survival as intramucosal esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35(7): 1045-1053.

35. Hahn HP, Shahsafaei A, Odze RD. Vascular and lymphatic properties of the superficial and deep lamina propria in Barrett esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32(10): 1454-1461.

36. Lewis JT, Wang KK, Abraham SC. Muscularis mucosae duplication and the musculo-fibrous anomaly in endoscopic mucosal resections for barrett esophagus: implications for staging of adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32(4): 566-571.

37. Mino-Kenudson M, Hull MJ, Brown I, et al. EMR for Barrett’s esophagus-related superficial neoplasms offers better diagnostic reproducibility than mucosal biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66(4): 660-666.

38. Ormsby AH, Petras RE, Henricks WH, et al. Observer variation in the diagnosis of superficial oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2002; 51(5): 671-676.

39. Hahn HP, Blount PL, Ayub K, et al. Intestinal differentiation in metaplastic, nongoblet columnar epithelium in the esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33(7): 1006-1015.

40. Kushima R, Vieth M, Mukaisho K, et al. Pyloric gland adenoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus with mucin immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic evaluation. Virchows Arch 2005; 446(5): 537-541.

41. Vieth M, Montgomery EA. Some observations on pyloric gland adenoma: an uncommon and long ignored entity! J Clin Pathol 2014; 67(10): 883-890.

42. Glickman JN, Blount PL, Sanchez CA, et al. Mucin core polypeptide expression in the progression of neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Hum Pathol 2006; 37(10): 1304-1315.

43. Abraham SC. Fundic gland polyps: common and occasionally problematic lesions. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2010; 6(1): 48-51.

44. Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, et al. Gastric adenomas: intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol 2002; 26(10): 1276-1285.

45. Abraham SC, Park SJ, Lee JH, et al. Genetic alterations in gastric adenomas of intestinal and foveolar phenotypes. Mod Pathol 2003; 16(8): 786-795.

46. Abraham SC, Park SJ, Mugartegui L, et al. Sporadic fundic gland polyps with epithelial dysplasia : evidence for preferential targeting for mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Am J Pathol 2002; 161(5): 1735-1742.

47. Singhi AD, Lazenby AJ, Montgomery EA. Gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation: a proposal for reclassification as oxyntic gland polyp/adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36(7): 1030-1035.

48. Ueyama H, Yao T, Nakashima Y, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type): proposal for a new entity of gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34(7): 609-619.

49. Srivastava A, Sanchez C, Cowan D, et al. Foveolar and serrated dysplasia are rare high-risk lesions in Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective outcome analysis of 214 patients. Hum Pathol 2010; 23(2): 742A.

50. Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs. traditional serrated adenoma (TSA). Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32(1): 21-29.

51. Ngamruengphong S, Wolfsen HC, Wallace MB. Survival of patients with superficial esophageal adenocarcinoma after endoscopic treatment vs surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11(11): 1424-1429.

52. Canto MI, Shin EJ, Khashab MA, et al. Safety and efficacy of carbon dioxide cryotherapy for treatment of neoplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy 2015; 47(7): 582-589.

53. Tsukashita S, Kushima R, Bamba M, Sugihara H, Hattori T. MUC gene expression and histogenesis of adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Cancer 2001; 94(2): 166-170.

54. Martínek J, Falt P, Gregar J, et al. Guidelines of the Czech gastroenterological society – endoscopic treatment of Barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal neoplasia. Gastroent Hepatol 2013; 67(6): 479-487.

Labels

Anatomical pathology Forensic medical examiner Toxicology

Article was published inCzecho-Slovak Pathology

2016 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Lungs „Hassalloid´s-like“ bodies in children with epidermolysis bullosa junctionalis and bart´s syndrome

- HPV-associated head and neck cancer: update and recommendations for practice

- New developments in molecular diagnostics of carcinomas of the salivary glands: “translocation carcinomas”

- Case report: Diagnosis under the microscope - disseminated echninococcosis, the multilocular form with protoscoleces

- Poorly differentiated sinonasal tract malignancies: A review focusing on recently described entities

- Observations of different patterns of dysplasia in barrett’s esophagus - a first step to harmonize grading

- Submucosal calcifying fibrous tumor of the stomach: A case report

- Czecho-Slovak Pathology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- HPV-associated head and neck cancer: update and recommendations for practice

- Poorly differentiated sinonasal tract malignancies: A review focusing on recently described entities

- Case report: Diagnosis under the microscope - disseminated echninococcosis, the multilocular form with protoscoleces

- New developments in molecular diagnostics of carcinomas of the salivary glands: “translocation carcinomas”

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career