-

Medical journals

- Career

The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among rural children aged 7–9 years during the economic transformation in Poland. 40 years’ observations: a case-control study

Authors: J. Rożnowski 1; L. Cymek 2; A. Rożnowska 3; M. Kopecký 4; F. Rożnowski 2

Authors‘ workplace: NZOZ Twój Lekarz Chełmno, Poland 1; Pomeranian University in Słupsk, Institute of Biology and Environmental Protection, Poland 2; Student at Medical University Gdansk, Poland 3; Palacký University Olomouc, Faculty of Health Science, Department of Specialised Subjects and Practical Skills, Czech Republic 4

Published in: Čes-slov Pediat 2017; 72 (7): 429-435.

Category: Original Papers

Overview

Objective:

The last 50 years in Poland has been a period of radical economic and demographic transformations. The deep economic crisis in 1980-1994 particularly affected people living in rural areas, especially in Pomerania, where for several years the net income of rural households fell by more than 40% year-on-year. This research aimed at analysing the prevalence of abnormal weight and the impact of various socioeconomic factors on the children’s development.Methods:

This paper presents the results of 3,262 children aged 7-9 years from two rural schools in Central Pomerania examined in years 1978-2005. Measurement of body weight and height were used to calculate each child's BMI, then according to the criteria of the International Obesity Task Force, were allocated to one of four weight status categories: underweight, normal BMI, overweight and obesity. The intergroup differences in unrelated qualitative variables were estimated using the χ2 test with the analysis of the odds ratio, and the effect of the socioeconomic factors on the prevalence of abnormal children’s weight status was analysed with the Mantel-Haenszel test.Results:

The study revealed that the number of children with abnormal weight status is increasing over time. The greatest rise of overweight and obese children was found between 1998 and 2005 (from 2.58% to 8.4%, p=0.002 among boys, and from 11.9% to 19.27%, p<0.0001 among girls). Simultaneously with the increasing of overweight and obese there was also an increase in the number of underweight children (from 6.64% to 14.8%, p=0.0003 among boys and from 9.46% to 16.08%, p=0.005, among girls). This trend has only recently been stopped.Conclusion:

To control and ultimately stop the continuing problems related to abnormal body weight, effective and well-coordinated measures have to be taken. The managed actions must combat both underweight and overweight at the same time at every possible level and by different professionals.Keywords:

underweight, overweight, obesity, rural childrenINTRODUCTION

Since the 1970s, anthropologists from the Pomeranian University in Słupsk (formerly the Pedagogical University) have been conducting research on the biological development of children and adolescents in Pomerania, Poland. For historical reasons, this region is extremely interesting in demographic terms. Since the end of World War II, two communities have lived here. The eastern part of Pomerania, which before World War II was a part of the Republic of Poland, is mainly populated by local people, who have lived in this area for hundreds of years. The western part of Pomerania, which was transferred to Poland after 1945 (in return for lost eastern territories), was mainly populated by Polish citizens who moved here from Vilnius, Polesia, Volhynia and Galicia. In addition, people from the today’s central Poland also moved to this land. As a result of such large-scale migrations a new community, with a modified gene pool, and living in completely different socioeconomic and biogeographical conditions gradually formed in this area [1]. Radical social, political and economic transformations (including almost ten years of deep economic crisis in the 1980s and early 1990s followed by a period of slow, steady development from the mid-1990s until the present day) in the last forty years caused huge changes in the living conditions of Polish families, their socioeconomic status, education level, fertility rate, wealth and life expectancy [2].

Detailed analysis of intergenerational changes in the physical development of Pomeranian children and adolescents requires constant observation because of, among other things, the ongoing significant cultural and socioeconomic transformations affecting living conditions in Poland [3, 4, 5]. Hence, the over forty-years of research on the status of the physical development of children and adolescents who are the second, third, and even fourth generation of migrants living in the cities, towns and villages of this part of Pomerania, and the collected data on various environmental factors that may influence this development seem so important.

The aim of this study is to show changes in the prevalence of abnormal weight (underweight, overweight and obesity) among rural children aged 7–9 years, examined in four 10-year stages (the last study was done after seven years).

METHODS

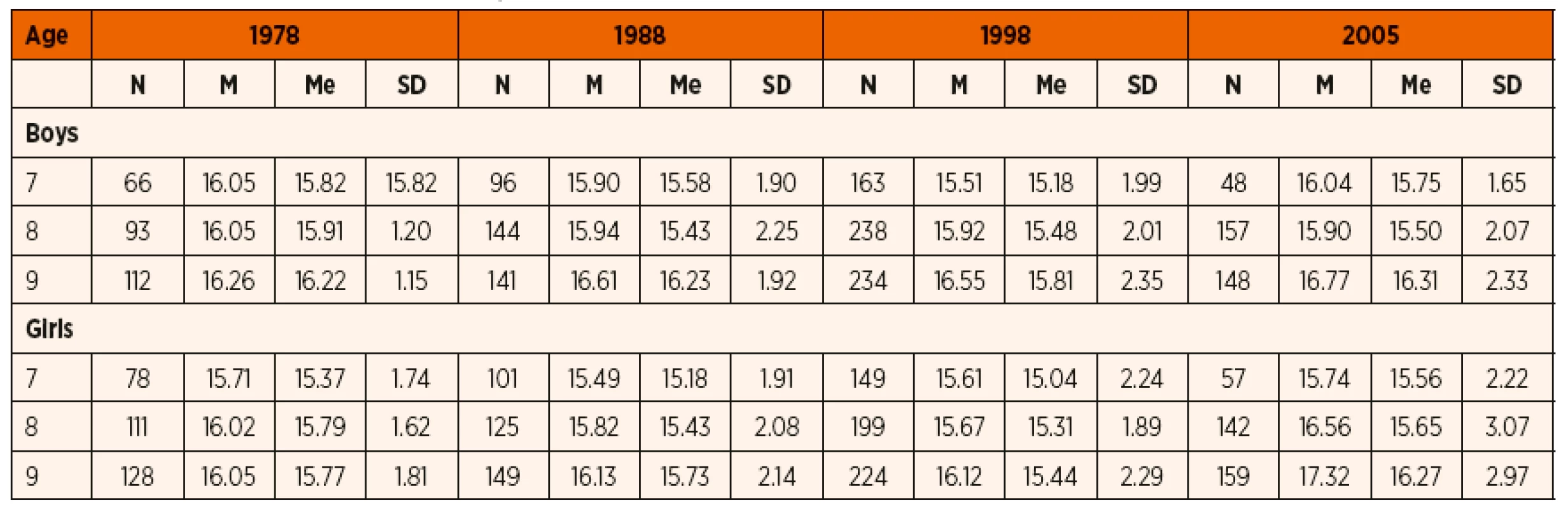

As part of the research into the development of rural children and adolescents from the Pomerania region, pupils from two rural primary schools (in Jezierzyce and Dębnica Kaszubska) in Central Pomerania were examined. The examination was always done in the autumn: stage 1 in 1978, stage 2 in 1988, stage 3 in 1998 and stage 4 in 2005. In total, 3,262 children (49.66% girls and 51.34% boys) were enrolled in the study. The examination was carried out after informed consent was obtained from parents, school management and education authorities, and approval from the relevant ethical committee. Only healthy children without any chronic diseases were qualified for the study. The numbers of examined children are presented in Table 1.

1. Statistics characteristics of BMI for boys and girls in four succesive cohorts.

Note: BMI – Body Mass Index, N – number, M – mean, Me – median, SD – standard deviation During the examination all children were dressed in gym clothes. Numerous anthropometric measurements were taken in line with standard measuring techniques. Among these, we used data on body weight (assessed with medical scales, accuracy of +/-0.1 kg) and body height (measured with an anthropometer in the upright position, accuracy of +/-0.1 mm). In addition, before the children were examined, their parents were asked to complete questionnaires related to the socioeconomic conditions in which they were living. In this article we used information about their education, the number of people living in the household, and the number of rooms in their home. Then, to analyse the effect of parents’ education on the nutritional status of their children, parents were grouped according to their educational level, i.e. primary, basic vocational, secondary and tertiary. In further analyses two groups of parents were established: those with primary and basic vocational education, and those with secondary and tertiary education. To categorize socioeconomic conditions the person-per-room index (PPR) was calculated based on the information on the number of occupants in a given household and the number of rooms. Because of the comparable physical development of children aged 7 to 9 years and methodology widely accepted by other authors, further analyses were conducted with a focus on all children together [5].

The results of individual measurements of body weight and height were used to calculate each child‘s BMI (kg/m2), which then, according to the criteria of the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF), were allocated to one of four weight status categories: underweight, normal BMI, overweight and obesity. Overweight and obesity was defined to pass through BMI of 25 and 30 kg/m2 respectively at age 18 and child underweight status was identified as thinness grade 2 (defined to pass through BMI of 17 kg/m2 at age 18 [6, 7]. Due to the small number or even lack of obese children in the first two stages of the study, they were pooled with the group of overweight children for further calculations.

The intergroup differences in unrelated qualitative variables were estimated using the χ2 test with the analysis of the odds ratio (OR), and the effect of the educational level of parents and the level of household crowding (PPR) on the prevalence of abnormal weight status among girls and boys was analysed with the Mantel-Haenszel test (M-H). Statistics are presented as crude values and adjusted for parents‘ education status and the household crowding level with odds ratios and 95% of confidence intervals [8, 9, 10]. The threshold for statistical significance was assumed to be p value <0.05. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using IBM SPSS.

RESULTS

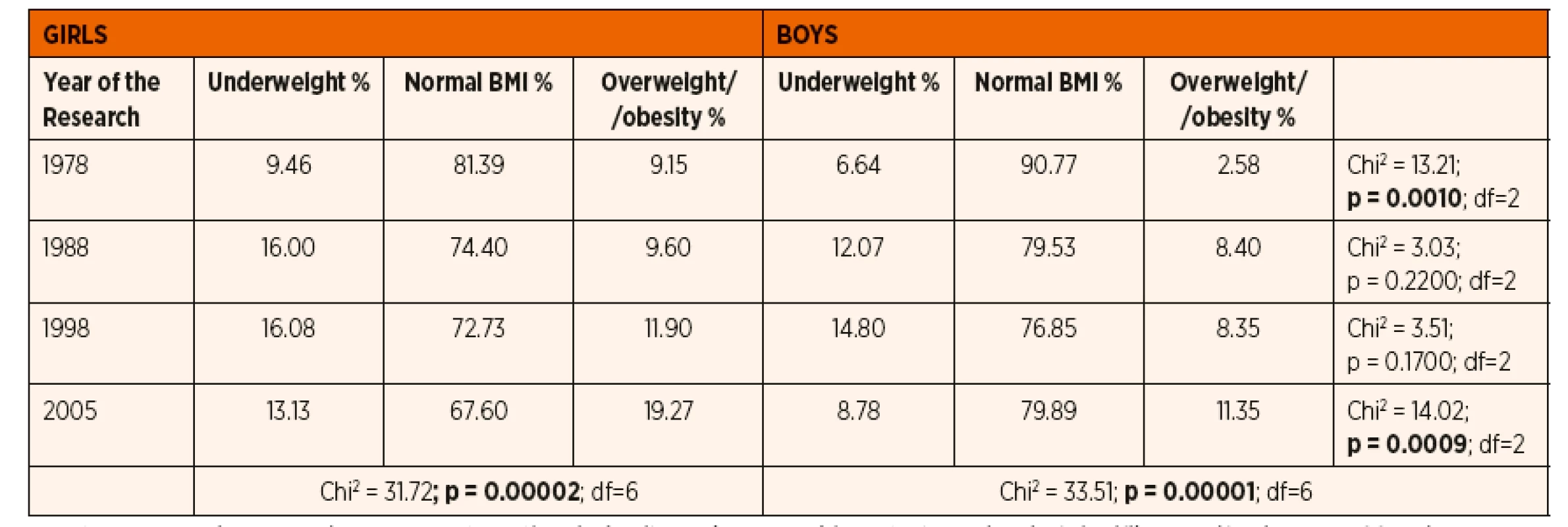

In each of the four study stages the percentage of boys with normal BMI (from 90.77% in stage 1 to 79.89% in stage 4) was higher than that of girls (81.39% and 67.6%, respectively). In stage 4 (2005) the number of boys with normal BMI was 3.04% higher in relation to stage 3 (1998). However, in the same period there was a further deterioration among girls, i.e. the number of girls with normal BMI decreased by another 5.13% to reach just 67.6%.

In subsequent years of the study consistently increase of the number of overweight/obese both in boys and girls was observed. The increase was greater among girls (from 9.15% in stage 1 to as much as 19.27% in stage 4; χ2 = 15.03; p<0.0001), compared to boys (from 2.58% in 1978 to 11.33% in 2005; χ2 = 16.34; p<0.0001) (Fig. 1 and 2). The greatest change in prevalence of children with overweight and obesity was found between 1978 and 1988 among boys (over a 3.5 –fold increase, from 2.58% to 8.40%; χ2 = 9.65; p=0.002). In stage 1 of the study not a singl e case of obesity was recorded among boys. The greatest 7.37% increase in the number of girls with overweight and obesity was recorded, between 1998 and 2005 (χ2 = 9.95; p<0.0001).

Fig. 1. Prevalence (in %) of overweight and obesity among boys aged 7–9 years in consecutive years of the study – based on International Obesity Task Force definition.

Fig. 2. Prevalence (in %) of overweight and obesity among girls aged 7–9 years in consecutive years of the study – based on International Obesity Task Force definition.

In stage 1 of the study (1978), the rates of underweight recorded among girls and boys were the lowest (6.64% for boys and 9.46% for girls), and they increased in subsequent decades to reach maximum values in stage 3 (14.8% for boys; χ2= 12.97; p=0.0003 and 16.08% for girls; χ2= 7.8, p=0.005) and decreased in stage four to 8.78% for boys (χ2=6.1; p=0.01) and 13.13% for girls (Fig. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3. Prevalence (in %) of underweight among boys aged 7–9 years in consecutive years of the study – based on International Obesity Task Force definition.

Fig. 4. Prevalence (in %) of underweight among girls aged 7–9 years in consecutive years of the study – based on International Obesity Task Force definition.

Between 1978 and 1988 there was a more than twofold increase in the percentage of boys with abnormal BMI, from 9.23% to 20.27% (χ2= 14.23; p=0.0002), while the rate of boys with underweight increased by 180%, from 6.68% to 12.07% (χ2=5.84; p=0.01), and the rate of boys with overweight and obesity increased more than three times (χ2=14.23; p=0.0002). In the same period the number of girls with abnormal BMI increased by 6.99% (χ2 = 4.43; p=0.03) (Fig. 3 and 4).

In 1988–1998 there was a slight decrease in the number of children with normal weight, which was due to an increased prevalence of underweight children (especially boys: from 12.07% to 14.8%), the unchanging percentage of boys with overweight and obesity, and a slightly increased percentage of girls with overweight and obesity. However, differences between these two stages were not statistically significant.

Abnormal weight status (underweight, overweight and obesity together) was significantly more often observed among girls compared to boys in each stage of the study (Table 2).

2. Prevalence (in %) of underweight, normal BMI, overweight and obesity in children aged 7-9 years by sex and examinated in consecutive years – based on the IOTF definition.

Note: BMI – Body Mass Index, IOTF – International Obesity Task Force, Chi – χ2 test, p – level of signifikance, df – degrees of freedom In stage 1 abnormal weight status was found twice more often among girls compared to boys (18.61% vs. 9.23%). In stage 4 of the study the rate of children with abnormal weight decreased from 23.15% to 20.11% among boys but increased among girls by 5.13% from 27.27% to as much as 32.40%.

The level of parents’ education (mother or father) and the level of household crowding (person-per-room index) slightly promoted the incidence of abnormal BMI among 7–9-year-old girls and boys, but their effect was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Between 1980 and 2008, mean BMI worldwide increased by 0.5 kg/m2 per decade in women and 0.4 kg/m2 per decade in men [11]. Statistics for the late 1990s show that almost one in five children in Western Europe and the USA were overweight or obese, and this problem concerned boys more frequently than girls [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. The 6th nationwide anthropological survey (NAS) of children and adolescents carried out in the Czech Republic in 2001 showed that the rates of overweight and obese children have dramatically risen compared to those reported in 1991 from 10.0% to 15.5% in boys and from 9.1% to 14.1% in girls aged 6–11 years. Whereas increase of mean BMI in the same group of children observed earlier (between years 1981 and 1991) was lower than 1.0% [17, 18]. A similar prevalence of overweight and obesity was found in a joint study conducted in Pomerania and Moravia, which showed slightly higher rates among Polish children. In both of these regions, we also noted similarities in the prevalence of underweight (slightly higher rates among Czech children) [19].

According to the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO), obesity in children should be regarded as a chronic disease requiring a special and multidisciplinary approach [20]. There is a rapid increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents, and to control this epidemic of obesity it is necessary to take comprehensive large-scale educational measures focused even on the youngest generation and promoting a healthy, balanced diet and physical activity. The lack of parental interest in active participation in obesity prevention programmes was observed among others by Kopecký in his study in the Olomouc region in 2014 [21]. The need for the continuous education of mothers as to the normal weight of children from the earliest months of their life is confirmed by our observational study on 163 mothers and their children aged 9 months to 6 years. We also found that after the completed schedule of regular medical appointments for mothers and their children in the first year of the life of the child, done in association with the necessary preventive immunization and control tests prescribed by standard neonatal care, maternal awareness as to the importance of their child’s body weight, and the need to keep it relevant to age, decreases drastically [22].

A study published in August 2016 in The Lancet involved a vast number (10,625,411) of participants from Asia, Australia and New Zealand, Europe and North America, and unquestionably showed that even a small decrease (from 20 kg/m2 to 18.5 kg/m2) and increase in BMI (from 25 kg/m2 to 27.5 kg/m2) increases the risk of premature death (by 13% and 7%, respectively) [23]. This demonstrates how important normal BMI is for life expectancy, and undoubtedly for the quality of life. Of note, as many as 45% of all mortality cases in the world among children under 5 years are related to abnormal weight status [24].

Each of the four cohorts of children analysed in 1978–2005 lived in completely different economic periods of Polish modern history: in times of the communist centrally-planned economy, then in over ten years of deep economic crisis in the 1980s, and the first decades of the free market economy. The situation seen during the second stage of research (1988), when food in Poland was rationed for several years, did not have as negative an impact on the physical development of children as one would expect. Similar findings were reported by Gomuła et al. [4], who analysed the prevalence of overweight among almost 70,000 children aged 7-18 years from different parts of Poland in 1966-2012. Comparable observations were made by Esquivel and González [25] in Cuba, where the incidence of overweight and abnormal fatness decreased in 1972 during an economic crisis, to rise again in 2005 as the economic situation improved.

A promising change was noted in 2005, when the trend of underweight children, both girls and boys, the rate of which had been increasing over decades, was reversed. This process strongly contributed to a slight increase in the percentage of boys with normal BMI in the last stage of the study.

Oblacińska et al. [26] examined 8,067 pupils aged 13–15 years in academic year 2005/2006 in four regions of Poland, including Pomerania, and found an almost twofold lower prevalence of underweight (4.3% for boys, 4.6% for girls) compared to our study covering the same period (8.78% for boys, 13.13% for girls). The differences can be attributed to the different age of participants, as well as to the fact that subjects were qualified for particular weight status groups based on percentile charts.

Studies carried out in the USA have shown that people living in areas of lower socioeconomic status (the poorer ones) have difficult access to supermarkets and to healthier food and, probably more importantly, food prices are higher there, so they more often reach for cheaper, lower-quality alternatives, such as fast-food, etc. [27, 28, 29, 30, 31]. Our study, particularly in 1988–1998, was carried out in such a poorer society. Conversely, the largest number of underweight children was noted not in the second stage (when food was rationed), but in the third stage of the study. This fact was probably associated with a significant deterioration of economic status in many families (the unemployment rate in these areas was then up to 45%), but fortunately this situation was temporary. As statistical yearbooks show, economic conditions do not improve at the same rate across the country. Some regions, societies and families have to wait a long time to be able to experience improvement.

Recent data for September 2015 (Global Nutrition Report) show the large-scale worldwide problem of abnormal body weight (1.9 billion adults are overweight or obese). 161 million children under the age of 5 are stunted, 51 million are wasted, and 42 million are overweight or obese. None of these children develop in a healthy way [32]. In our study, the greatest rise in the prevalence of overweight and obesity was observed over the last two decades, which is consistent with global data [12, 13, 14, 15, 33, 34].

The level of education of the parents (mother or father) and the level of crowding (person-per-room index) slightly promoted the incidence of abnormal BMI among 7–9-year-old girls and boys, but their effect was not statistically significant. The small percentage of parents with secondary or tertiary education from rural areas analysed in the first two stages of research was probably the primary reason why the study showed a lack of significant impact on the nutritional status of children, in contrast to other studies carried out in Poland, Czech Republic and in United States, where this effect was clear [3, 18, 35, 36].

The level of crowding (the number of occupants per room) is one of the recognized factors useful in the monitoring of socioeconomic factors. Theoretically, children who have more space (lower PPR value) have better conditions to fully realize their developmental potential, and the larger the family and the greater the number of persons per room, the greater the probability of poverty in a family, which in turn can contribute to abnormal weight status (underweight, overweight or obesity) [37].

In the analysed period the rural areas were affected for a long time by marked poverty, and families lived in previously built dwellings, but in combination with the decline in total fertility rate in rural families in the last 40 years this had no effect on the nutritional status of children examined in our study. Moreover, the number of occupants per room in the analysed population had no significant effect on the final results.

CONCLUSIONS

Modernization and economic development have improved the standard of living and services available to people in rural area in Pomerania, as in many other regions of the world. Unfortunately, there has been a dramatic increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity, but the problem of underweight among children has not been eliminated. However, a positive trend was observed in the last decade, both among boys and girls. To tackle and ultimately stop the rapidly growing problem of nutritional disorders, large-scale, effective and well-coordinated measures on many levels must be undertaken. These managed actions must be aimed at eliminating the problem of underweight and overweight at the same time at every possible level and by different professionals.

Došlo: 10. 7. 2017

Přijato: 18. 9. 2017

Jaroslaw Roznowski, M.D., PhD.

NZOZ Twoj Lekarz

Lunawska 1

86 200 Chelmno

Poland

e-mail: jarek6550@gmail.com

Sources

1. Kersten K. Repatriacja ludności polskiej po II wojnie światowej. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Ossolineum, 1974.

2. Kaliński J, Landau Z. Gospodarka Polski w XX wieku. Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne 1999; 1–391.

3. Bielicki T, Szklarska A, Kozieł S, Ulijaszek SJ. Changing patterns of social variation in stature in Poland: effects of transition from a command economy to the free-market system? J Biosoc Sci 2005; 37 : 427–434.

4. Gomula A, Nowak-Szczepanska N, Danel DP, Koziel S. Overweight trends among Polish schoolchildren before and after the transition from communism to capitalism. Economics and Human Biology 2015; 19 : 246–257.

5. Chrzanowska M, Kozieł S, Ulijaszek SJ. Changes in BMI and the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Cracow, Poland, 1971–2000. Economics and Human Biology 2007; 5 : 370–378.

6. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000; 320 : 1–6.

7. Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA. Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 2007; 335 (7612): 94.

8. Moczko JA. Cofunding variables in observational studies and their influence on obtained results. Przegląd Lekarski 2009; 66 (10): 857–860.

9. Robins J, Breslow N, Greenland S. Estimators of the Mantel-Haenszel variance consistent in both sparse data and large-strata limity models. Biometrics 1986; 42 : 311.

10. Mannocci A. The Mantel-Haenszel procedure. 50 years of the statistical method for cofounders control. JPH 2009; 6 (4): 338–340.

11. Finucane MM, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body mass index since 1980: Systemic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 coutry-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011; 377 (99765): 557–567.

12. Livingstone B. Epidemiology of childhood obesity in Europe. Eur J Pediatr 2000; 159 (Suppl 1): 14–34.

13. Lobstein T, Rugby N, Leach R. Obesity in Europe – 3 International Obesity Task Force March 15, Brussel 2005.

14. Kelishadi R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev 2007; 29 : 62–76.

15. Petersen S, Brulin C, Bergstrom E. Increasing prevalence of overweight in young schoolchildren in Umea, Sweden, from 1986 to 2001. Acta Paediatrica 2003; 92 : 848–853.

16. Ritchie LD, Ivey SL, Woodward-Lopez G, Crawford PB. Alarming trends in pediatric overweight in the United States. Sozial-Und Praventivmedizin 2003; 48 : 168–177.

17. Vignerová J, Riedlová J, Bláha P, et al. 6.celostátni antropologický výzkum dĕti a mládeže 2001, Česka republika: souhrnné výsledky. Praha: PřF UK, 2006.

18. Kobzová J, Vignerová J, Bláha P, et al. The 6th nationwide anthropological survey of children and adolescents in the Czech Republic in 2001. Cent Eur J Publ Health 2004; 12 (3): 126–130.

19. Rożnowski J, Cymek L, Kopecký M. Two countries, two environments of life – one problem: prevalence of weight disturbances among children and youth aged 7-15. Polish Journal of Enviromental Studies 2008; 17(4A): 361–366.

20. Farpour-Lambert NJ, et al. Childhood Obesity Is a Chronic Disease Demanding Specific Health Care a Position Statement from the Childhood Obesity Task Force (COTF) of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). Obesity Facts 2015; 8 : 342–349.

21. Kopecký M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in children between the ages of 6 and 7 and the attitude of parents towards primary prevention in the Olomouc Region. Hygiena 2016; 61 (1): 4–10.

22. Rożnowski J, Leks B, Rożnowska A, Kopecký M. When maternal misperception of their child’s weight status begins? Obesity Facts 2017; 10 (Supp.1); 258, T4P128; doi:10.1159/000468958.

23. Di Angelantonio E, et. al (The Global Mortality Collaboration). Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-paricipant data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 2016; Aug 20; 388 (10046): 776–786.

24. Black RE, et al. Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Lancet 2013; 382 (9890): 427–451.

25. Esquivel M, González C. Excess weight and adiposity in children and adolescents in Havana, Cuba: Prevalence and trends, 1972 to 2005. MEDICC Rev 2010; 12 (2): 13–18.

26. Oblacińska A, Tabak I, Jodkowska M. Demograficzne I regionalne uwarunkowania niedoboru masy ciała u polskich nastolatków. Przegl Epidemiol 2007; 61 : 785–793.

27. Wang MC, Kim S, Gonzalez AA, et al. Socioeconomic and food-related physical characteristics of the neighbourhood environment are associated with body mass index. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007; 61 : 491–498. [PubMed:17496257].

28. Macdonald L, Cummins S, Macintyre S. Neighbourhood fast food environment and area deprivation – substitution or concentration? Appetite 2007; 49 : 251–254. [PubMed: 171896621].

29. Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local environment on residents’ diets: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Am J Public Health 2007; 92 : 1761–1767. [PubMed: 12406805].

30. Block JP, Scribner RA, DeSalvo KB. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income: a geographic analysis. Am J Prev Med 2004; 27 : 211–217. [PubMed: 15450633].

31. Kipke MD, Iverson E, Moore D, et al. Food and park environments: neighborhood-level risks for childhood obesity in east Los Angeles. J Adolesc Health 2007; 40 : 325–333. [PubMed: 17367725].

32. Global Nutrition Report. Actions and Accountability to Advance Nutrition and Sustainable Development. Washington DC: 2015; 1–201.

33. Kautiainen S, Rimpela A, Vikat A, Virtanen SM. Secular trends in overweight and obesity among Finnish adolescents in 1977-1999. Int J Obes 2002; 26 : 544–552.

34. Lobstein TJ, James WPT, Cole TJ. Increasing level of excess weight among children in England. Int J Obes 2003; 27 : 1136–1138.

35. Gurzkowska B, Kułaga Z, Litwin M, et al. The relationship between selected socioeconomic factors and basic anthropometric parameters of school-aged children and adolescents in Poland. Eur J Pediatr 2014; 173 : 45–52.

36. Ziol-Guest KM, Dunifon RE, Kalil A. Parental employment and children’s body weight: Mothers, others, and mechanisms. Soc Sci Med 2013; 95 : 52–59. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.004.

37. Łaska-Mierzejewska T, Olszewska E. Antropologiczna ocena zmian rozwarstwienia społecznego populacji wiejskiej w Polsce, w okresie 1967-2001. Badania dziewcząt. [Anthropological Evaluation of Changes in Social Stratification of Rural Population in Poland between 1967–2001], Studia i Monografie AWF (95). Warszawa: AWF, 2003.

Labels

Neonatology Paediatrics General practitioner for children and adolescents

Article was published inCzech-Slovak Pediatrics

2017 Issue 7-

All articles in this issue

- Hepatitis A epidemy in children hospitalized at the Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, University Hospital, Brno, from March 2016 to March 2017

- Rotaviruses and other agents causing gastroenteritis in patients hospitalized at the Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, University Hospital, Brno, in 2015–2016

- Syphilis congenita recens – case report

- Survey of adverse childhood experiences in the Czech Republic

- Longitudinal monitoring of somatic parameter changes in children during adolescence

- A rare case of congenital thyroglossal cyst with cysto-tracheal fistula: case report

- The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among rural children aged 7–9 years during the economic transformation in Poland. 40 years’ observations: a case-control study

- Czech-Slovak Pediatrics

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- A rare case of congenital thyroglossal cyst with cysto-tracheal fistula: case report

- Survey of adverse childhood experiences in the Czech Republic

- Syphilis congenita recens – case report

- Rotaviruses and other agents causing gastroenteritis in patients hospitalized at the Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, University Hospital, Brno, in 2015–2016

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career