-

Medical journals

- Career

ACCIDENTAL FINDING OF SYNCHRONOUS BILATERAL DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU IN A YOUNG MAN REFERRED TO MASTECTOMY DUE TO GYNECOMASTIA – AND WHAT IF LIPOSUCTION HAVE BEEN USED? CASE REPORT

Authors: R. Horta 1,2,3; F. Schmitt 3,4; N. Pereira 5; H. Gervásio 6

Authors‘ workplace: Viseu, Portugal ; Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, CUF Hospital 1; Department of Plastic, Aesthetic and Reconstructive Surgery, Centro Hospitalar São João Hospital, Porto, Portugal 2; University of Porto, Faculty of Medicine, Porto, Portugal 3; University of Porto, IPATIMUP – Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology, Porto, Portugal 4; Obstetrician-gynecologist in private practice 5; Department of Medical Oncology, CUF Hospital, Viseu, Portugal 6

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 62, 1-2, 2020, pp. 46-49

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer in males is a rare condition with an incidence of 0.5–0.7% of all cases of breast carcinoma.

1-3 Approximately 5% (range 2.3–17%) of male breast cancer (MBC) cases are ductal carcinomas in situ (DCIS). Presenting symptoms are similar to female tumors, and the two most characteristic clinical symptoms include a slowly growing subareolar mass and nipple discharge.3 The origin of the majority of female DCIS is the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU).1,4 However, the male breast lacks this anatomical structure. Hittmair showed that low grade forms of DCIS do not require the TDLU as site of origin.4 Therefore, DCIS in males is likely to arise from the epithelium of larger ducts. 4,5 The vast majority of male breast cancers are invasive ductal carcinomas. Invasive lobular carcinoma is rare (1%), presumably due to the lack of lobular development in the male breast. 3

The most prevalent risk factor for male breast cancer is related with higher age and most have been attributed to testicular malfunction and increased estrogen.1,2 Other proposed risk factors include family history, breast cancer genes mutations (BRCA2 > BRCA1), Cowden and Klinefelter syndromes, alcohol consumption, and liver disease.

Gynecomastia, defined as excessive breast tissue development, is a common condition in male adolescents. There is no proven direct link between gynecomastia and male breast cancer.2 Association between gynecomastia and DCIS has rarely been reported in adults and very few cases have been described in teenagers.1-3 Here we report a case of a bilateral DCIS, accidentally found in a 26-year-old obese man treated for gynecomastia.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old man presented with a long-standing stable bilateral gynecomastia. He was a smoker (half a pack per day) and had a history of morbid obesity. He was advised to lose weight and stop smoking, and his weight was reduced by 20 kg to 85 kg (body mass index 29.2), but despite the loss of weight, bilateral gynecomastia had become more prominent. There was no family history of cancer. Physical examination revealed asymmetrical bilateral breast growth (right breast being larger – Figure 1), consisting of adipose tissue associated to glandular tissue under the areola, without palpable masses. Testicular ultrasound was normal. Sex hormones, thyroid and hepatic functions were also normal. Breast ultrasound showed bilateral breast enlargement without nodules or suspicious lesions. No axillary, supraclavicular, or cervical lymphadenopathy were clinically obvious. He had fully developed secondary sexual characteristics, including normal-size and descended testicles.

1. Preoperative: Bilateral asymptomatic gynecomastia

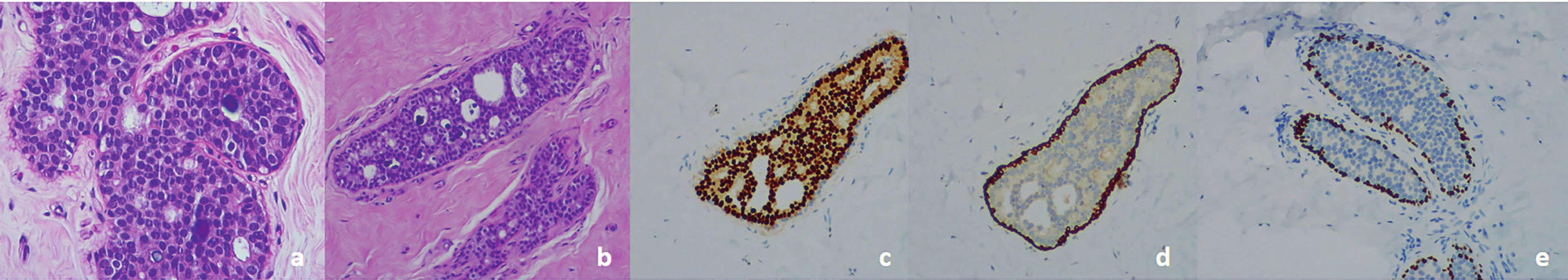

Because of the psychosocial impact on his quality of life, he underwent bilateral subcutaneous mastectomy and simultaneous mastopexy by a circumareolar incision. No concomitant liposuction was used. Two suction drains were placed (each for side) and they were removed after 24 hours. The postoperative period was uneventful. Macroscopic examination showed central fibrosis surrounded by adipose tissue. Histologic examination revealed multifocal intraductal proliferation with a solid cribriform pattern and calcification, without necrosis, accounting for a low-grade intraductal breast carcinoma. After DCIS detection, total evaluation of the specimen was done to rule out invasive cancer. DCIS was present in 30 of 111 examined fragments at the right breast, and in 26 of 71 fragments at the left breast. The luminal cells were diffuse and strongly positive for estrogen receptor. CK 5 and P63 were positive only in the myoepithelial cells surrounding the ducts (Figure 2). Resection margins were histologically tumor free.

2. a) Histology. Low-grade DCIS, cribriform, H&E staining. b) Note the presence of a duct filled by cells with the characteristics of low-grade DCIS next to a normal duct. Absence of necrosis and mitosis, H&E staining.

c) Low-grade DCIS. Uniform staining of neoplastic cells for estrogen receptors.

d) Low-grade DCIS. Myoepithelial cells positive for cytokeratin 5 Note negativity for this marker inside the duct.

e) Low-grade DCIS. Myoepithelial cells positive for P63

The case was discussed at our institution’s tumor board meeting. Close surveillance and follow-up every 6 months were recommended with physical examination and chest x-ray, and genetic counseling. No adjuvant treatment was needed. Peripheral blood karyotype was normal, ruling out Klinefelter syndrome. A complete analysis of BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes showed no mutation, and there was no P53 or PTEN mutation. However, a rare variant in the ATM gene was detected – ATM c.1229T>C (p.Val410Ala).

He remains well and under regular follow up, with no evidence of recurrent disease at 18 months follow-up (Figure 3).

3. Postoperative result after 1 year

DISCUSSION

There is no proven link between gynecomastia and cancer.2 Indeed, pubertal gynecomastia is considered to be a phase of normal development and spontaneously regresses in teenagers within 1–2 years. Although not evident in our patient, risk factors for the development of DCIS include hyperprolactinemia 1 and exogenous estrogens.

Genetic risk factors include a family history of breast cancer, BRCA-2 mutation, and Klinefelter syndrome, whereas Cowden and Li-Fraumeni syndromes have not been associated with MBC.2 Our patient’s genomic and karyotypic thorough analysis was negative for any genetic contribution, despite detection of a rare variant in the ATM gene, which has a conflicting interpretation of pathogenicity.6 Some studies indicated that there is a significant prevalence of ATM mutations in breast and ovarian cancer families suggesting increased susceptibility to breast cancer of ATM mutations.7

Obesity is a risk factor for adult male breast cancer, doubling the risk of an individual to develop MBC. 2 In our patient, obesity could have contributed to the development of gynecomastia. Indeed, in overweight teenage boys, an increased conversion of testosterone to estrogen within the peripheral adipose tissue could be involved in its development (androgens are aromatized to estradiole and androstenedione to estrone). This could have exacerbated the already existing estrogen excess and, therefore, his predisposition to breast cancer.

The management of male patients with DCIS has not been extensively studied; therefore, no firm guidelines for treatment exist, but the recommended treatment in the literature is modified radical mastectomy without axillary dissection.1,2,5 Because the majority of these lesions are subareolar, nipple excision may be required. Radiation therapy, tamoxifen, or chemotherapy are not required in men after total mastectomy for DCIS.

Senger et al 8 performed a review of 452 patients that included two cases of pseudogynecomastia (0.4%), in addition to a literature review where a total of 15 incidental findings were identified: ductal carcinoma in situ (12 cases), atypical ductal hyperplasia (two cases) and infiltrating ductal carcinoma (one case). Because no significant pathological findings were detected in a cohort of 452 cases with 2178 slides, and because of associated costs on routine histopathological tissue examinations, he proposed that not all tissue samples obtained by mastectomy for gynecomastia necessitate histopathological evaluation. The decision to proceed to histopathological evaluation should include major and minor risk factor assessments, such as evidence of Klinefelter syndrome, a pathological process with an acute onset or rapid progression, a palpable irregular mass, bloody nipple discharge or other clinical presentations that have been reported to be associated with malignant or premalignant lesions, such as retroareolar pain and swelling. Given the rarity, guidelines for MBC screening by mammogram and/or magnetic resonance imaging are ill-defined.

Qureshi et al 5 suggested that in the preoperative planning of gynecomastia surgery for breast diameters >6 cm, though effective, excisional techniques subject patients to large, visible scars.

In addition, ultrasound-assisted liposuction has emerged as a safe and effective method for the treatment of gynecomastia with minimal external scarring. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction has several advantages over suction-assisted lipectomy in the treatment of gynecomastia, including the selective emulsification of fat leaving higher density structures, such as fibroconnective tissue, relatively undamaged. At higher energy settings, ultrasound-assisted liposuction is effective in removal of the denser, fibrotic parenchymal tissue that suction-assisted lipectomy is inefficient in removing. It also affects the dermis, allowing for skin retraction in the postoperative healing period, and reduces physical demand for large-volume liposuction, allowing the surgeon improved attention to precise contouring.

However, liposuction without histopathological evaluation of the liposuctioned tissue may be problematic. Voulliaume 9 reported two patients with an unusual complication: the liposuction of a malignant tumor. In one patient, liposuction was used for gynecomastia correction, which was in fact a breast cancer. Three years after liposuction, the patient developed an invasive and infiltrative cancer, with metastatic axillary lymph nodes, and pectoralis muscle invasion just above the clavicle. The second patient was treated by liposuction for an ankle “lipoma”, but it proved to be a liposarcoma after recurrence with deep invasion (internal malleolus and Achilles tendon), requiring enlarged resection and flap coverage. He advocated that in order to avoid liposuction and dissemination of a malignant tumor, preoperative investigations have to search clinical peculiarities evoking the diagnosis. An unilateral “gynecomastia”, irregular, hard or painless mass, patients with > 40-years, family history of breast cancer, must incite the surgeon to perform a classical excision, just as a recurrent “lipoma”, deeply located, voluminous or rapidly growing, situated on the limbs or in the humeroscapular area. Doubtful cases must be rejected for liposuction, and treated by a surgical excision with strict safety margins and complete anatomopathologic examination of the lesion.

In our case, fortunately we decided to perform bilateral mastectomy and after diagnosis of bilateral ductal carcinoma no other treatment was required.

Liposuction has become a very useful technique for gynecomasty correction, however, the risk of dissemination of an unknown malignant tumor should be present. In atypical cases, surgical excision should be performed.

Ethical Standards: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding: The authors have no financial disclosures to declare.

Conflict of interest: All named authors hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contribution: Study design: Ricardo Horta; Data acquisition: Ricardo Horta, Fernando Schmitt, Helena Gervásio; Data analysis and interpretation: Ricardo Horta, Nuno Pereira; Manuscript preparation: Ricardo Horta, Nuno Pereira; Manuscript editing: Ricardo Horta; Manuscript review: Ricardo Horta, Fernando Schmitt, Helena Gervásio.

Corresponding author:

Ricardo Horta MD, PhD

Rua Heróis de França, nº 850, P2, 3º Direito

4450-156 Matosinhos Sul - Porto, Portugal

E-mail: ricardojmhorta@gmail.com

Sources

1. Staerkle RF., Lenzlinger PM., Suter SL., Varga Z., Melcher GA. Synchronous bilateral ductal carcinoma in situ of the male breast associated with gynecomastia in a 30-year-old patient following repeated injections of stanozolol. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006, 97 : 173–6.

2. Lemoine C., Mayer SK., Beaunoyer M., Mongeau C., Ouimet A. Incidental finding of synchronous bilateral ductal carcinoma in situ associated with gynecomastia in a 15-year-old obese boy: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2011, 46 : 17–20.

3. Brents M., Hancock J. Ductal Carcinoma In situ of the Male Breast. Breast Care (Basel). 2016, 11 : 288–90.

4. Hittmair AP., Lininger RA., Tavassoli FA. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in the male breast: a morphologic study of 84 cases of pure DCIS and 30 cases of DCIS associated with invasive carcinoma--a preliminary report. Cancer. 1998, 83 : 2139–49.

5. Qureshi K., Athwal R., Cropp G., Basit A., Adjogatse J., Bhogal RH. Bilateral synchronous ductal carcinoma in situ in a young man: case report and review of the literature. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007, 7 : 710–12.

6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/127332/

7. Thorstenson YR., Roxas A., Kroiss R., Jenkins MA., Yu KM., Bachrich T., Muhr D., Wayne TL., Chu G., Davis RW., Wagner TM., Oefner PJ. Contributions of ATM mutations to familial breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3325–33.

8. Senger JL., Chandran G., Kanthan R. Is routine pathological evaluation of tissue from gynecomastia necessary? A 15-year retrospective pathological and literature review. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2014, 22 : 112–6.

9. Voulliaume D., Vasseur C., Delaporte T., Delay E. [An unusual risk of liposuction: liposuction of a malignant tumor]. About 2 patients. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2003, 48 : 187–93. French.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2020 Issue 1-2-

All articles in this issue

- AN OVERVIEW AND OUR APPROACH IN THE TREATMENT OF MALIGNANT CUTANEOUS TUMOURS OF THE HAND

- ENHANCED RECOVERY PROTOCOL FOLLOWING AUTOLOGOUS FREE TISSUE BREAST RECONSTRUCTION

- SKIN SUBSTITUTES IN RECONSTRUCTION SURGERY: THE PRESENT AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

- GUNSHOT INJURIES OF THE OROFACIAL REGION

- INDICATION AND IMPORTANCE OF RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERIES OF FACIAL SKELETON IN MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY: REVIEW

- Editorial

- CURRENT OPTIONS IN PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS FOR MICROVASCULAR ANASTOMOSIS PATENCY: REVIEW

- ACCIDENTAL FINDING OF SYNCHRONOUS BILATERAL DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU IN A YOUNG MAN REFERRED TO MASTECTOMY DUE TO GYNECOMASTIA – AND WHAT IF LIPOSUCTION HAVE BEEN USED? CASE REPORT

- RED BREAST SYNDROME (RBS) ASSOCIATED TO THE USE OF POLYGLYCOLIC MESH IN BREAST RECONSTRUCTION: A CASE REPORT

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- RED BREAST SYNDROME (RBS) ASSOCIATED TO THE USE OF POLYGLYCOLIC MESH IN BREAST RECONSTRUCTION: A CASE REPORT

- AN OVERVIEW AND OUR APPROACH IN THE TREATMENT OF MALIGNANT CUTANEOUS TUMOURS OF THE HAND

- GUNSHOT INJURIES OF THE OROFACIAL REGION

- SKIN SUBSTITUTES IN RECONSTRUCTION SURGERY: THE PRESENT AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career