-

Medical journals

- Career

Giant basal carcinoma on the forehead and why should prevent them - case report

Authors: M. De Fré 1,2; N. Vermeersch 1,2; Ch. Fré De 3; M. Ulicki 3; K. Smets 3; T. Tondu 1,2; F. Thiessen 1,2

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Antwerp University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium 1; ZNA Middelheim Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium 2; Department of Dermatology, Antwerp University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium 3

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 61, 1-4, 2019, pp. 24-27

INTRODUCTION

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in Belgium1 (1). Because of their generally slow growth and low metastatic potential, they are often considered “relatively benign”. The latter combined with the high prevalence, the increasing incidence worldwide and the relative increase of aggressive histologic subtypes creates a dangerous situation2. If BCCs are inadequately treated or not followed up carefully, large, aggressive and potentially lethal carcinomas can form. Giant BCC (>5cm) or super giant BCC (>20 cm) have substantially augmented metastatic and corresponding mortality rates3. This not only affects the patient directly by increasing morbidity and mortality, but it also has an important impact on the public health funds2. We present a case of 61-year-old male who had to go through major reconstructive surgery due to the inadequate treatment and/or follow-up of a “simple” BCC on the forehead.

CASE REPORT

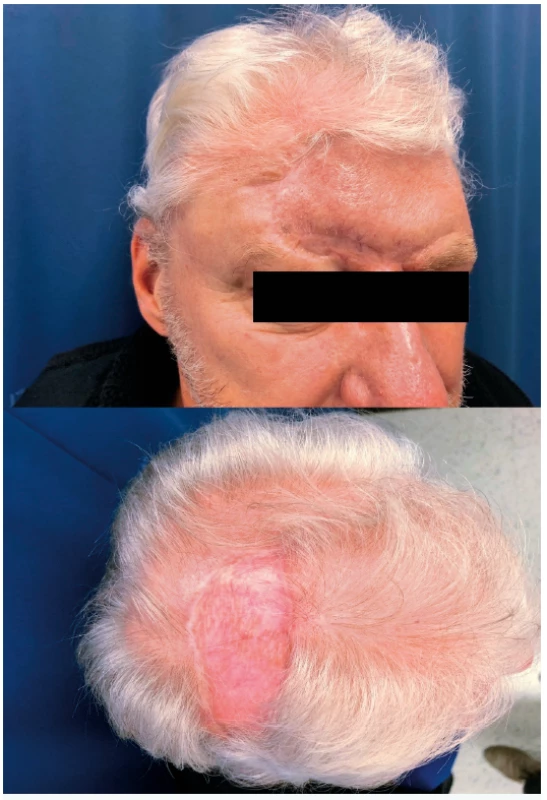

A 61-year old Caucasian male was referred to our Oncology department because of a recurring BCC on the forehead. After a thorough history and review of the patient’s medical records we found that the first excision of a small BCC took place seven years ago. Subsequent incomplete excisions were performed in the following years. The patient was a non-smoker, there was no history of radiotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy and the patient denied excessive sun exposure or sunburns. His family history was non-contributory. At the time of presentation, a large indurated lesion was observed in the right frontal area of the forehead. There were no complaints of pain or pruritus, however he experienced slight tenderness on palpation. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy. Routine blood tests showed no abnormalities. A CT scan with intravenous contrast of the patient’s head revealed a hypodense subcutaneous invasive mass (5.2 cm laterolateral x 4.0 cm craniocaudal) located frontally, crossing the midline to the right side of the forehead. There was no erosion of the underlying bone or intracranial extension of the tumour. The patient was referred to the department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery for complete excision of the BCC and reconstruction afterwards (Figure 1).

1. Preoperative state, large indurated lesion in the right frontal area of the forehead

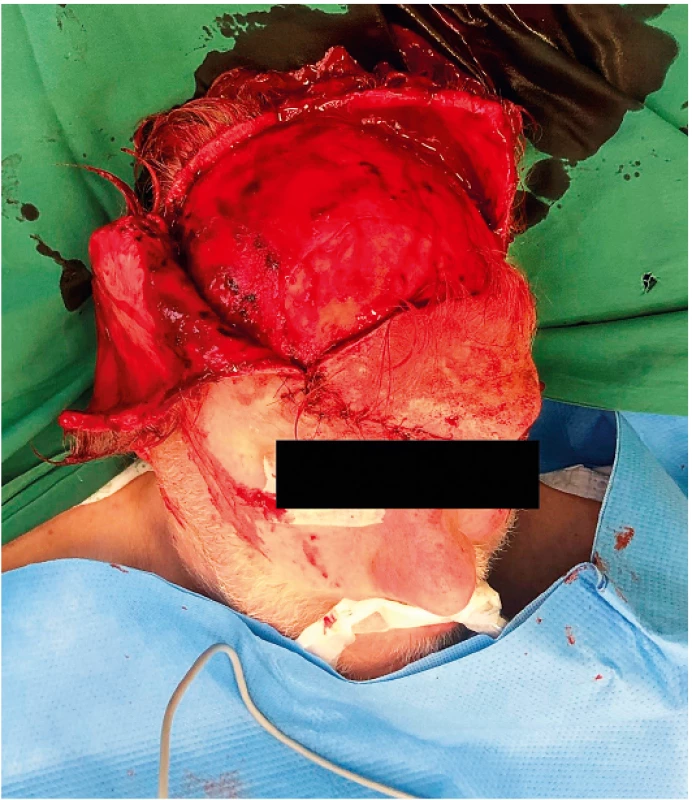

Initially, wide and radical local excision was performed with >1cm peripheral margins (Figure 2a). The defect was covered using a split-thickness skin graft harvested from the thigh, using a pneumatic dermatome. The lesion (7.5 x 6.0 x 0.8 cm) (Figure 2b) was sent for histological assessment, with additional specimens of the left lateral border (2.8 x 0.4 x 0.2 cm) and periosteum (2.0 x 0.5 x 0.1 cm). A giant infiltrative BCC (> 5cm, Pt3) with limited zones of perineural invasion and no lymphovascular involvement was described. Residual tumour cells were observed in the left lateral border, as well as in the periosteum. Therefore, a ring-shaped re-excision including the underlying periosteum was performed one month later, creating a defect of 15.0 x 12.0 cm (Figure 3). Reconstruction was achieved using a left frontal fasciocutaneous flap. This fasciocutaneous flap was rotated to the initial defect. The secondary defect was closed with an advancement flap of the scalp and the donor sites were covered using a split-thickness skin graft from the upper limb. Microscopy showed no residual tumour lesion. The patient recovered well and no adjuvant radiotherapy was deemed necessary after reviewing by Oncology department. After three months and after consultation with the patient, we decided to correct the low position of the left eyebrow to obtain a fully satisfying result (Figure 4). There were no signs of recurrence or metastasis at 6 - and 12-month follow-up. A strict annual follow-up was recommended.

2. a. Perioperative state, wide and radical local excision of the lesion with >1cm peripheral margins

Fig. 2. b. Resection specimen (7.5 x 6.0 x 0.8 cm)

3. Ring-shaped re-excision including the underlying periosteum

4. Status 6 months post-operative

DISCUSSION

This case, among many others, demonstrates once again why we started referring to these tumours as basal cell “carcinomas” instead of “epitheliomas”. BCC remains a malignant tumour characterized by aggressive local invasion, destructing all surrounding tissues including cartilage and bone. Furthermore, BCC can metastasize to regional lymph nodes and/or distant organs. With its high prevalence, incidence rates rising worldwide, the relative increase of aggressive subtypes and high recurrence rates, big challenges lie ahead of us2,4,5.

Clear guidelines on how to diagnose, treat and manage patients suffering from BCC have already been drafted5. The greatest problem lies in the underestimation of the need for impeccable management of this cancer. The large majority (70–90%) of these lesions are located in the head and neck area4,6. Simple excision of a BCC requires at least a 4 mm margin, potentially creating a large tissue defect in a complex anatomical region where skin reserves for coverage are limited5. These situations could potentially lead to incomplete excisions, increased morbidity and mortality, poor aesthetic outcomes as well as increased costs. The same applies for the follow-up after complete excision of a BCC. Firstly, the initial lesion has respectively a 5 - and 10-year recurrence rate of 4% and 12% after standard excision, considering it is a low recurrence risk BCC. These recurrence rates increase with increasing size of the lesion, difficult locations, aggressive pathologic features and other predisposing factors7. Secondly, patients with a first BCC have respectively a 40% and 60% chance of developing a new BCC in the next 5 and 10 years. For non-first BCCs the chances are respectively 82% and 91% 7. Thirdly, patients who suffered from a BCC have a 2 to 3 times higher chance of developing a subsequent malignant melanoma, as well as other skin malignancies5. The reasons listed above demand careful follow-up of these patients. Furthermore, follow-up consultations should be conducted by physicians with sufficient expertise in naked-eye examination, looking for skin cancer. Preferably, they should master dermatoscopy, since it increases diagnostic accuracy from 58% to 84% over naked-eye examination2. This is beneficial for the patient directly by improving diagnosis and it also prevents many unnecessary referrals, biopsies and excisions2.

The development of giant BCCs should be avoided at all cost. BCCs grow approximately 2.8–5.6 mm/year, with some growing faster2. Rates of metastasis and mortality increase with increasing tumour size. The overall metastatic rate of BCCs is < 0.1%. However, larger BCCs, respectively > 3 cm, > 10 cm and > 25 cm have metastatic rates of 1.9%, 45%, and 100%3. Giant BCCs also have a higher chance of subclinical extension of the tumour, with corresponding recurrence rates of 68%3. Recurrent tumours also raise treatment difficulties regarding reconstruction after initial wide (incomplete) excision4. Neglected and inadequate treatment of the primary lesion are the most important contributing factors responsible for the increased size of giant BCCs8. Due to their generally slow growth, BCC’s have a detectable latent stage in which treatment is minimally invasive, easy and economical. This is why initial, adequate therapy is the key.

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates the disastrous consequences of negligent treatment and follow-up of a common basocellular carcinoma. On the other hand, despite the accumulation of unfortunate events in the patient’s history, a complete excision and satisfying reconstruction was achieved after multiple surgeries. Tumour free resection margins were demonstrated upon pathological examination of the excised specimen and no recurrence was diagnosed (12 months after the last excisional surgery). The necessity for vigilance in the approach to these skin neoplasms, encompassing timely diagnosis, adequate treatment and careful follow-up, should be emphasised. This might seem obvious, but demands great dedication from the concerned physicians, due to the enormous amounts of patients with BCC(s). The progression to giant BCCs should be avoided. Increased size of BCCs is correlated with increased recurrence rate, metastatic rate, morbidity, mortality, treatment difficulties, and overall costs. Fortunately, BCCs have a detectable latent stage in which treatment is minimally invasive, easy and economical. Timely diagnosis and adequate surgical therapy is the key in the treatment of BCCs.

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines were followed, including the Declaration of Helsinki from the World Medical Association (WMA).

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Maxime De Fré, MD

Antwerp University Hospital

Wilrijkstraat 10

B-2650 Edegem

Belgium

E-mail: maxime.defre@gmail.com

Sources

1. Callens J, Van Eycken L, Henau K. Epidemiology of basal and squamous cell carcinoma in Belgium: the need for a uniform and compulsory registration. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereol. 2016, 30 : 1912–18. doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jdv.13703.

2. Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Ongenae K. Is early detection of basal cell carcinoma worthwhile? Systematic review based on the WHO criteria for screening. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 174 : 1258–65. doi.wiley.com/10.1111/bjd.14477.

3. Di Lorenzo S, Zabbia G, Corradino B. A Rare Case of Giant Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Abdominal Wall: Excision and Immediate Reconstruction with a Pedicled Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator (DIEP) Flap. Am. J. Case Rep. 2017, 18 : 1284–88.

4. Florescu IP, Turcu EG, Carantino AM. The curious case of a forehead metatypical basal cell carcinoma. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol, 2018, 59 : 345–52.

5. Work Group C, Invited Reviewers A, Kim JYS. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78 : 540–59.

6. Kwon C-S, Awar O Al, Ripa V. Basal cell carcinoma of the scalp with destruction and invasion into the calvarium and dura mater: Report of 7 cases and review of literature. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 47 : 190–97.

7. Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2015, 88 : 167–79.

8. \Celić D, Lipozenčić J, Ljubojević Hadžavdić S. A Giant Basal Cell Carcinoma Misdiagnosed and Mistreated as a Chronic Venous Ulcer. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2016, 24 : 296–98.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2019 Issue 1-4-

All articles in this issue

- České souhrny

- Bilobed flap in facial reconstruction

- Free-flap monitoring: review and clinical approach

- Giant basal carcinoma on the forehead and why should prevent them - case report

- Use of medial femoral condyle flap and anterolateral thigh free flap in proxymal tibial posttraumatic non-union with multiple anastomosis - case report

- The impact of aesthetic plastic surgery on body image, body satifaction and self-esteem

- Reconstruction of deep head burn with a free flap - a case study

- Acknowledgemets to reviewers

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- The impact of aesthetic plastic surgery on body image, body satifaction and self-esteem

- Free-flap monitoring: review and clinical approach

- Bilobed flap in facial reconstruction

- Use of medial femoral condyle flap and anterolateral thigh free flap in proxymal tibial posttraumatic non-union with multiple anastomosis - case report

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career