-

Medical journals

- Career

Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction and Motivation of General Nurses

Authors: J. Vévoda 1; Š. Vévodová 1; H. Sobotková 1

Authors‘ workplace: Fakulta zdravotnických věd, Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci 1

Published in: Prakt. Lék. 2020; 100(Supplementum): 44-49

Category:

Overview

Introduction: General nurses play a major role in the healthcare system. In consideration of their irreplaceable position it is necessary for the managements of healthcare providers to identify the key factors of their job satisfaction and work motivation, and to identify factors of job dissatisfaction. The managements can, consequently, create a work environment that enables nurses to cope with psychological and physical requirements of their profession, decreases turnover, and raises the quality of patient care.

Aim: This article aims to identify the subjective order of personal preferences of individual factors related to job satisfaction of general nurses and their subjective perception of saturation of factors that influence job satisfaction, together with finding the greatest divergence.

Method: A cross-sectional study was carried out in the first half of 2018. A questionnaire about motivation factors was completed by 462 respondents, i.e. 28.2%. We used the Euclidean distance model to determine the order of factors.

Results: The factors with the highest subjective preference were Salary, Interpersonal work relationships with peers, Interpersonal work relationships with other professions, Interpersonal work relationships with supervisors, and Recognition. Factors with the highest saturation related to nurse’s working environment included Patient care, Interpersonal work relationships with supervisors, Interpersonal work relationships with peers, and Interpersonal work relationships with other professions. The greatest divergence occurred in factors Salary and Recognition.

Conclusion: Although salaries in healthcare continue to rise, nurses in this sector experience job dissatisfaction which can be influenced by employees only to a limited extent. There is, however, a considerable potential for non-financial recognition which does not require additional finance. In consideration of the fact that the respondents in this study perceived positively their working relationships with supervisors, hospital managements should work towards the best possible use of this factor and train their managers to employ it.

Keywords:

general nurse – job satisfaction – work motivation.

Introduction

Working in healthcare is physically and mentally demanding. Healthcare professionals face human suffering on daily basis, often including death. It is therefore necessary to build a favourable working environment which would minimize turnover. Causes of high turnover are multidimensional, often contradictory, and it is difficult to compare or generalize them (Nagaya, 2018). Alexander, Lichtenstein, Oh & Ullman (1998) and Takase (2010) suggested that turnover tendency among workers is a multistage process consisting of psychological, cognitive and behavioural components, combining social and experiential orientation, attitudes to work and a decision-making process that leads to the decision to leave their current employer and to seeing the decision through. Gurková, Soósová, Haroková, Žiaková, Šerfelová & Zamboriová (2013) confirmed that job satisfaction affects turnover of nurses and is related to the decision-making process of deciding whether to continue working for their current employer or whether to stay employed in the field.

Turnover may result in a significant decrease in the quality of the healthcare system and may lead to an increase in patient care cost (Borda & Norman, 1997a; Borda & Norman, 1997b). In reaction to a negative change concerning their financial situation, healthcare workers may resign from their jobs, may seek employment in another sector of the economy, or may find work abroad. Stabilized and motivated staff represent one of the key conditions for providing high quality healthcare.

One of the key objectives of healthcare policy will be creating such working conditions in healthcare that will motivate healthcare workers to stay in work. If employers do not create favourable working conditions, staff shortage will increase. The task of the manager is to identify the value preferences of employees and their order on their personal value scale. Such knowledge is essential for effective personnel management. According to past research aimed at identifying the personal values of general nurses, at the time of the emerging financial and economic crisis and at its height, nurses identified the factor “Salary” as the most significant factor on the personal values scale, followed by the factor “Patient care.” The third most important factor was identified as “Job security.” The factor “Salary”, however, was at the same time subjectively perceived as the least saturated (fulfilled) by the employer (Ivanová, Nakládalová & Vévoda, 2012; Vévoda, Ivanová, Nakládalová & Mareckova, 2010). It is unclear whether the personal value scale of the healthcare staff and the subjective saturation has changed in the current economic expansion, during which the salaries of healthcare staff were increased, or whether it remains the same as in the years of the economic recession.

Aim

This article focuses on job satisfaction of general nurses working in acute inpatient care in hospitals (hereafter referred to as GN) in the Olomouc Region (hereafter referred to as OR), Zlín Region (hereafter referred to as ZR), and Moravian-Silesian Region (hereafter referred to as MSR).

We formulated three objectives of our study:

Objective 1 To identify the subjective order of personal preferences of individual job satisfaction factors of GN.

Objective 2 To identify the subjective order of perceived saturation of individual working environment factors of GN.

Objective 3 To find out if there exist the greatest differences between the subjective order and the subjectively perceived saturation of individual work satisfaction factors of GN.

Method

We employed a cross-sectional study in our research. To collect data, we used a motivation factors questionnaire which was based on the principles of Herzberg’s Two-Factor Motivation Theory (Herzberg, Mausner & Snyderman, 1993). Motivational and hygienic factors provided the basis for creating the questionnaire scales. The first part of the questionnaire comprised of questions aimed at sociodemographic characteristics. In the second part of the questionnaire, GN were asked to make a list of subjectively perceived order of the factors from 1 to 16 (see Tab. 1), with 1 being the most important factor and 16 the least important, and with none of the numbers being used more than once. The respondents then ordered the factors according to their subjective perception of the factor saturation by the employer, where factor 1 was the least and factor 16 the most saturated. Each number could be used once only.

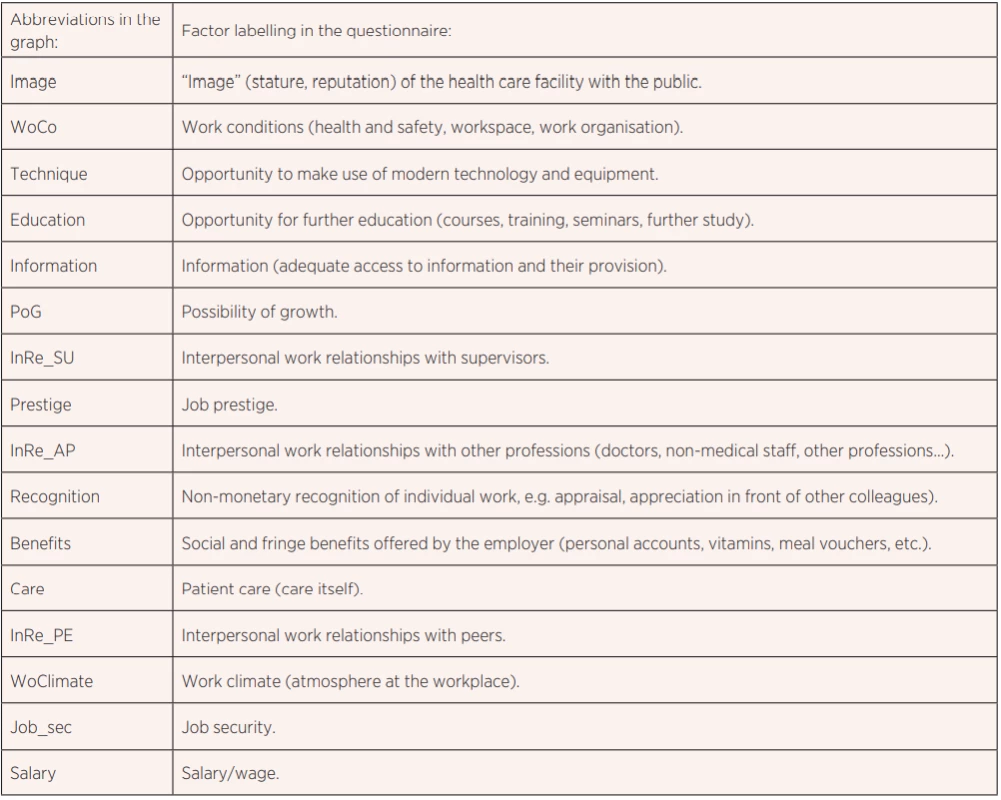

1. The environmental factors listed in the question sheet and their respective codes used in the graph

The designed questionnaire was tested in research in 2004 and 2006 (Vévoda, Ivanová, Nakládalová & Mareckova, 2010; Ivanová, Nakládalová & Vévoda, 2012). Tab. 1 shows the working environment factors listed in the questionnaire and the abbreviations used in following graphs.

We used the number of GN in different regions of CR as the basic measure of representativeness. The representation of nurses corresponds with the population structure. The respondents were selected intentionally with an exclusion criterion which stated that the length of their employment had to be longer than one year. This condition helped us to rule out employees that did not complete their process of adaptation with their current employer.

The research was carried out from February to April 2018. According to the Institute of Health Information and Statistics of the Czech Republic, hereafter referred to as IHIS (IHIS CR, 2018), the number of GN and midwives employed in acute care in CR was 48,074. Subsequently, we calculated the number of jobs in regions where the research was conducted: 2,973 in Olomouc Region, 6,666 in Moravian-Silesian Region, and 2,206 in Zlín Region.

We distributed a total of 1,631 questionnaires and expected a 35% return, basing the percentage of return on our previous experience, as GN are overloaded with many statistical surveys and paperwork. The expected percentage of return was in proportion to the sample size in individual regions. The questionnaires were distributed in white opaque envelopes, and after they were filled in, they were put into sealed boxes located in an easily accessible place. In this way the anonymity of the respondents was ensured. The boxes were emptied in each hospital once a month by the researches. The return was 28.2%, from the previously overestimated number, which equals to 462 questionnaires. To ensure that the sample is representative, it was necessary to obtain answers from 571 respondents with the Confidence level 95 and the called margin of error 4 % according to the Sample Size Calculator (https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm#one). The number of answers obtained thus reached 80.9% of the respondents needed to ensure the representativeness of the research in the three regions.

Statistical data processing was performed using the MS Excel 2010 programme and IBM SPSS 19.0 with the use of the Euclidean distance model.

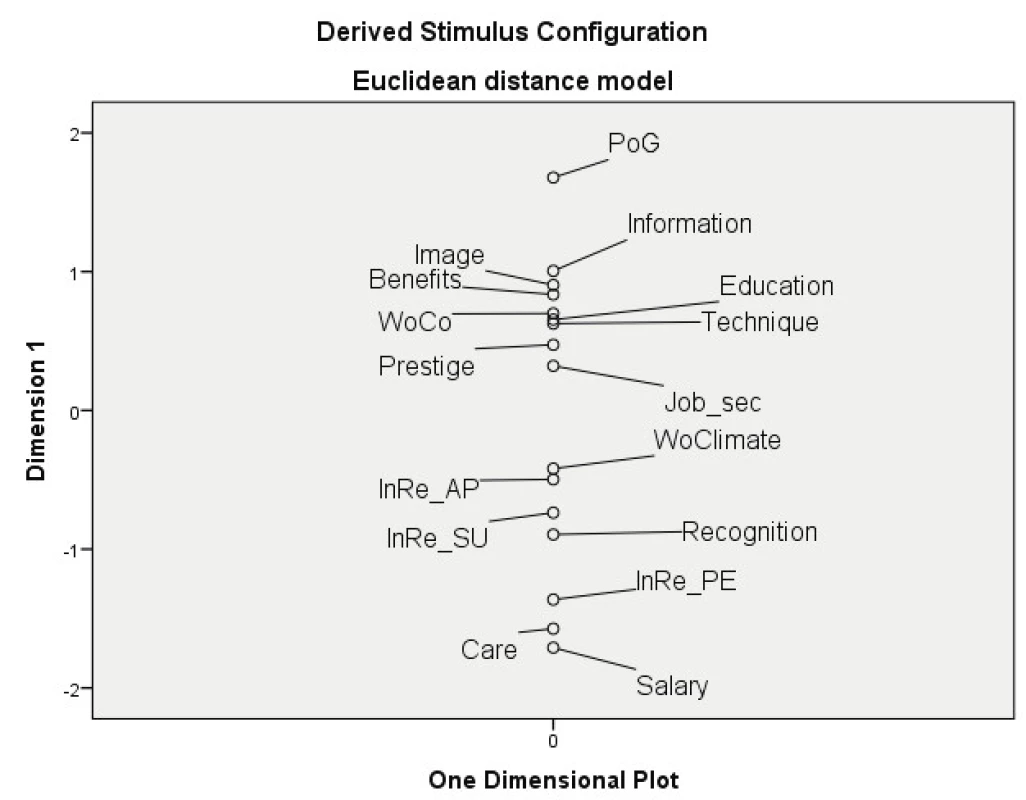

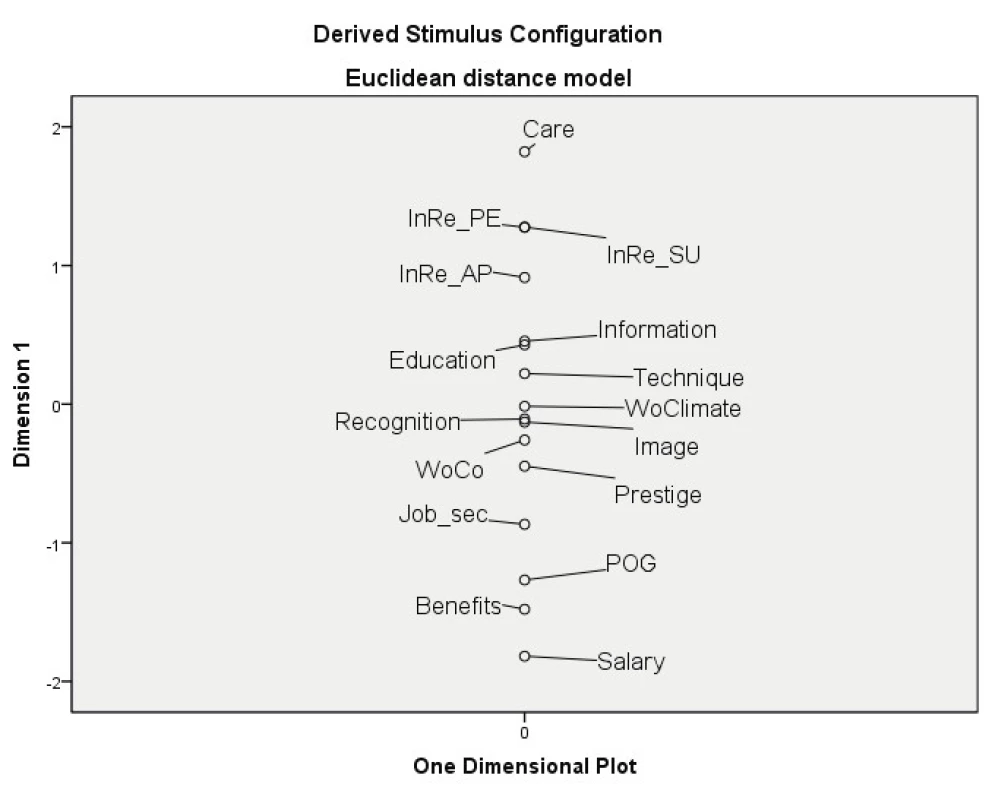

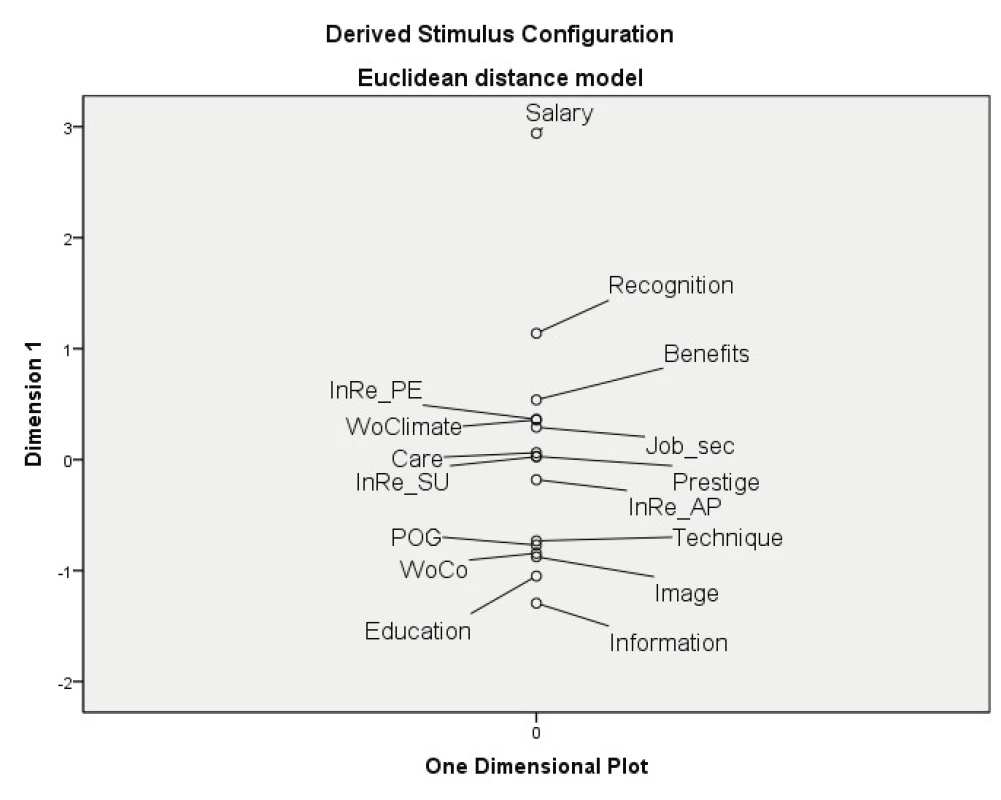

We employed descriptive statistics to summarize the sociodemographic characteristics of GN (total years of professional experience, years of professional experience at the current employer, age, gender). The Euclidean distance model, a one-dimensional statistic test belonging to the group of cluster analysis tests, was used to find out the order and distance between individual factors of work environment. The test classifies factors into clusters based on their mutual similarity, and it determines the order of the factors and the distances in which the factors are related to each other. If the factors are grouped together, it shows that they are considerably homogeneous. If, on the other hand, they are scattered along the axis, it reflects their heterogeneity. The significance of the factors is given by their distance from others. If the factors are distant from one another, their significance in relation to the neighbouring factors, as well as to other factors, increases. The numbers along the X-axis (One Dimensional Plot) and Y-axes (Dimension 1) used in the graph are dimensionless numbers, and thus they have no role in the interpretation.

Results

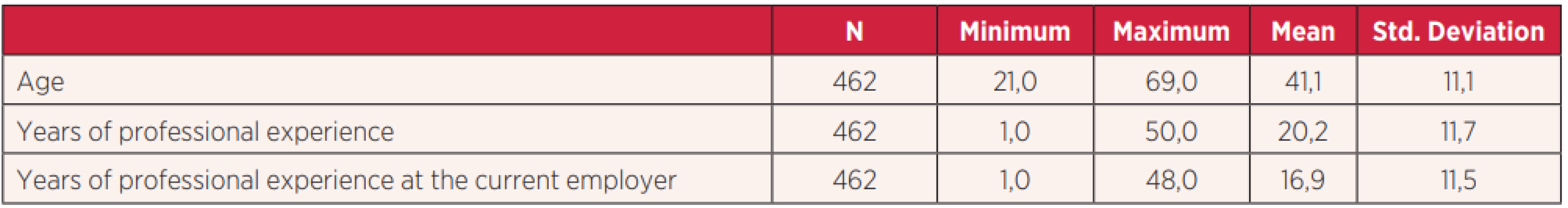

There are still predominantly women employed in nursing, as the sample included only 8 men. Three respondents did not choose to indicate their gender. Other sociodemographic characteristics included in the research are presented in Tab. 2.

2. The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample of GN.

Regarding Objective 1, the Euclidean distance model cluster analysis helped us to identify that in terms of subjectively perceived preferences of work environment factors the GN demonstrate the strongest preference for the factors from the first cluster, i.e. “Salary,” “Care,” and “Interpersonal work relationships with peers.” The second cluster includes the factors “Recognition,” “Interpersonal work relationships with supervisors,” “Interpersonal work relationships with other professions,” and “Work climate.” “Possibility of growth” represented the factor with the least preferences, as shown in Fig. 1.

1. Order of personal preferences of GN (reads from bottom to top).

Concerning Objective 2, GN consider “Care” to be the most saturated factor out of the subjectively perceived saturation of factors, followed by the cluster which concerns interpersonal work relationships: “Interpersonal work relationships with peers,” “Interpersonal work relationships with supervisors,” and “Interpersonal work relationships with other professions.” The least saturated factor was “Salary” (Fig. 2).

2. Perception of factor saturation (reads from top to bottom).

Regarding Objective 3, the highest divergence between personal preferences and subjectively perceived saturation occurs in “Salary” and “Recognition,” as shown in Fig. 3. The divergences model shown in graph 3 were calculated on the basis of simple differences in score of individual factors between the subjective preferences shown in Fig. 1 and perceived saturation shown in Fig. 2.

3. Differences between personal preferences and perceived saturation (reads from top to bottom).

Discussion

The topic of salaries has been the top issue in the Czech healthcare for several decades and it involves the GN themselves, their associations, political representation and the public. “Salary” is the factor which GN have preferred over a long period of time, but which, from their point of view, is one of the least saturated factors (Ivanová, Vévoda, Nakládalová & Marečková, 2012). In 2011, when Nakládalová, Vévoda, Ivanová & Mareckova (2011) conducted their research, the average wage of GN was 24,740 CZK and the average salary was 28,145 CZK (IHIS CR, 2012). In the second quarter of 2011, the average gross monthly nominal wage (hereafter referred to as “average wage”) recalculated to the number of employees in the whole national economy was 23,984 CZK (CSZO, 2018). In the 2017 survey, the average wage of GN was 30,381 CZK and the average salary was 36,808 CZK (IHIS CR, 2018). In the second quarter of 2017, the average gross monthly wage recalculated to the number of employees in the national economy was 29,346 (CSZO, 2018). The above indicates that the average wage and salary of GN are higher than the average wage in the national economy. Although wages of healthcare workers, including GN, are frequently increased, they are among the subjectively least saturated factors (Nakládalová, Vévoda, Ivanová & Mareckova, 2011). Despite the real increase in wages, nurses feel financially undervalued. Wage increases, however, are possible to achieve only if the Public Health Insurance system in the Czech Republic is provided with additional financial resources, which results in increasing the tax burden of the population.

It needs more than just a good salary to keep GN motivated to continue working in a hospital (McHugh & Ma, 2015). The factor “Salary” may be in opposition to factor “Care.”

Work represents an essential part of people’s lives. It is thus clear that the “Care” factor holds the second position on the values scale of GN and, at the same time, it is the most subjectively saturated factor. This is, furthermore, one of the most balanced factors. GN consider their job to be a mission and they expect that their employers—hospitals—enable them to fulfil the mission. And GN perceive that this really happens. The position of this factor, similarly to the factor “Salary,” corresponds with previous findings (Ivanová, Vévoda, Nakládalová & Marečková, 2012; Nakládalová, Vévoda, Ivanová & Mareckova, 2011). Work in nursing is highly demanding and it may become the source of job dissatisfaction, while excessive workload may influence employee performance (Kaur & Gujral, 2017). The changing situation on the labour market will force managements to adjust to the current situation where there is a high number of vacancies. Managements must provide a well-organized work that will meet the demands of healthcare workers instead of searching for factors of external motivation. The work itself may become one of the principal factors of motivation.

The third position in the list of personal preferences is held by “Interpersonal work relationships with peers.” It holds similar position from the point of view of subjectively perceived saturation. The top positions of the scale are occupied by other interpersonal work relationships: “Interpersonal work relationships with other professions” and “Interpersonal work relationships with supervisors.” Multidisciplinary teams are the basis for patient care and interpersonal work relationships among members of a team may lead to both job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction. It is important to determine how team members complete a task in cooperation with others, whether their behaviour is friendly and supportive or vice versa (Alam & Mohammad, 2010). Yang et al. (2012) suggest in their research that friendly working environment correlates with employee performance and job satisfaction, and correlates negatively with turnover. Cooperation among team members is considered by employees to be one of reasons for job satisfaction (Lockhart, 2020).

Work relationships with supervisors are one of the key factors of the interpersonal work relationships factors. Managers have a major role in a number of healthcare professions, especially in acute care (Konstantinou & Prezerakos, 2018). Leadership qualities of managers and their position in a team influence the behaviour of other team members. Managers who provide other team members with feedback and create supportive environment may be the cause of job satisfaction (Lockhart, 2020). The so-called millennial generation of nurses consider supportive leadership to be the principal factor contributing to job satisfaction (O’Hara, Burke, Ditomassi & Palan Lopez, 2019).

Contrary to the previous findings of Ivanová, Vévoda, Nakládalová & Marečková (2012), the fourth position in the list of personal preferences is newly occupied by “Recognition,” which is at the same time the second factor with the highest discrepancy between expectation and perceived saturation. Previous research showed that this position was held by the factor “Job security,” which ranked on a lower position in this research as a consequence of the end of the economic crisis and a shortage of nurses on the labour market (Ivanová, Vévoda, Nakládalová & Marečková, 2012). It seems, therefore, that GN seek not only financial reward, but also non-financial reward, for example in the form of praise from a superior nurse, a doctor, etc. In addition, verbal, or otherwise expressed praise is not an expense for employers.

Recognition demonstrates to the employees that the management pays attention to them and appreciates their demanding work. In order to exploit the motivational potential of this factor, it is essential that recognition is always timely and reflects real achievements. If employees do a good job at work, they expect that their managers will praise their work.

Conclusion

Regardless of the crisis or expansion in the economic cycle, GN have long been dissatisfied with the financial reward of their demanding work. On the other hand, “Patient care” is among the factors that GN have long preferred, but unlike the financial reward, they are satisfied with its saturation by employer. The research indicates that economic expansion reduces the preference of the “Job security” factor which was replaced by non-monetary “Recognition.” Healthcare managements in the regions where the survey was conducted should reflect the change and focus more on forms of non-financial rewards, such as praise. It is furthermore possible to consider training managers in the use of soft skills.

Limitations

Limitations are represented by low response rate which leads to difficulties in generalizing the obtained results. Nurses who did not fill the questionnaire could have held different opinions.

Acknowledgements

Supported by RVO: 61989592

Ethical Aspects and Conflict of Interest

No conflicts.

Mgr. Jiří Vévoda, Ph.D.

Faculty of Health Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc

Mgr. Šárka Vévodová, Ph.D.

Faculty of Health Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc

Mgr. Hana Sobotková, Ph.D

Faculty of Health Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc

Sources

- Alam, M., & Mohammad, J. (2010). Level of Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave Among Malaysian Nurses. Business Intelligence Journal, 3(1), 123-137.

- Alexander, J., Lichtenstein, R., Oh, H., & Ullman, E. (1998). A causal model of voluntary turnover among nursing personnel in long-term psychiatric settings. Research in Nursing & Health, 21(5), 415-427.

- Borda, R., & Norman, I. (1997a). Factors influencing turnover and absence of nurses: a research review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 34(6), 385-394.

- Borda, R., & Norman, I. (1997b). Testing a model of absence and intent to stay in employment: a study of registered nurses in Malta. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 34(5), 375-384.

- CSZO Prague: Average wages - News Releases. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/prumerne-mzdy

- Gurková, E., Soósová, M., Haroková, S., Žiaková, K., Šerfelová, R., & Zamboriová, M. (2013). Job satisfaction and leaving intentions of Slovak and Czech nurses. International Nursing Review, 60(1), 112-121.

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. (1993). The motivation to work. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A.: Transaction Publishers.

- IHIS CR Prague: Wages and salaries in health services in 2011. (2012). Retrieved from https://www.uzis.cz/sites/default/files/knihovna/30_12.pdf

- IHIS CR Prague: ZDRAVOTNICTVÍ ČR: PERSONÁLNÍ KAPACITY a ODMĚŇOVÁNÍ 2017. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.uzis.cz/sites/default/files/knihovna/nzis_rep_2018_E04_Personalni_kapacity_Odmenovani_2017.pdf

- Ivanová, K., Nakládalová, M., & Vévoda, J. (2012). Pracovní satisfakce všeobecných sester v ČR podle hodnotových distancí. Pracovní lékařství, 64(4), 119-122.

- Ivanová, K., Vévoda, J., Nakládalová, M., & Marečková, J. (2012). Trendy pracovní spokojenosti všeobecných sester. Kontakt, XV(2), 115-127.

- Kaur, M., & Gujral, H. (2017). Work Load On Nurses And It’s Impact On Patientcare. Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 6(5), 22-26.

- Konstantinou, C., & Prezerakos, P. (2018). Relationship Between Nurse Managers‘ Leadership Styles and Staff Nurses‘ Job Satisfaction in a Greek NHS Hospital. American Journal of Nursing Science, 7(3-1), 45-50.

- Lockhart, L. (2020). Strategies to reduce nursing turnover. Nursing Made Incredibly Easy!. 18(2).

- McHugh, M., & Ma, C. (2015). Wage, Work Environment, and Staffing: Effects on Nurse Outcomes [Online]. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 15(3-4), 72-80.

- Nagaya, Y. (2018). A Review of Factors Affecting Nursing Turnover in Japan. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 12(3).

- Nakládalová, M., Vévoda, J., Ivanová, K., & Mareckova, J. (2011). Pracovní spokojenost všeobecných sester na lůžkových odděleních nemocnic. Pracovni Lekarstvi, 63(1), 18-23.

- O’Hara, M., Burke, D., Ditomassi, M., & Palan Lopez, R. (2019). Assessment of Millennial Nurses’ Job Satisfaction and Professional Practice Environment. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(9), 411-417.

- Takase, M. (2010). A concept analysis of turnover intention: Implications for nursing management. Collegian, 17(1), 3-12.

- Vévoda, J., Ivanová, K., Nakládalová, M., & Mareckova, J. (2010). Pracovní spokojenost všeobecných sester. PROFESE on-line, 3(3), 207-220.

- Yang, L., Yang, H., Chen, H., Chang, M., Chiu, Y., Chou, Y., & Cheng, Y. (2012). A study of nurses’ job satisfaction: The relationship to professional commitment and friendship networks. Health, 04(11), 1098-1105.

Labels

General practitioner for children and adolescents General practitioner for adults

Article was published inGeneral Practitioner

-

All articles in this issue

- Patient satisfaction with the management of acute postoperative pain in a medical facility

- Nurses‘ Role in Prescribing Medication

- Coping of students in study programs General nursing and Paramedic

- Initial experience with the Czech version of the Sydney Swallow Questionnaire

- Clinical simulation as a method in midwifery teaching

- Quality of Life of Patients after Polytrauma in Relation to the Injury Severity Score

- Development of healthcare professionals’ roles – a physician’s perspective

- Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction and Motivation of General Nurses

- Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Oral Care in Mechanical Ventilated Patients

- General Practitioner

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction and Motivation of General Nurses

- Coping of students in study programs General nursing and Paramedic

- Nurses‘ Role in Prescribing Medication

- Clinical simulation as a method in midwifery teaching

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career