-

Medical journals

- Career

Healing of endodontic periodontal lesion after non-surgical treatment

Authors: E. Hidoussi 1; H. Sarraj 1; N. Zokkar 1; W. Batbout 1; N. Douki 2; L. Bhouri 1

Authors‘ workplace: Faculty of Dental Medicine, Department of Restorative Dentistry-Endodontics, Monastir, Tunisia 1; Sahloul Hospital of Sousse, Department of Restorative Dentistry-Endodontics, Tunisia 2

Published in: Česká stomatologie / Praktické zubní lékařství, ročník 120, 2020, 2, s. 50-55

Category: Case Report

Overview

Introduction, aim: An endo-perio lesion is one of the common problems associated with the tooth. The simultaneous presence of pulp-related condition and inflammatory periodontal disease can complicate diagnosis and treatment planning. Furcation involvement presents major challenges in periodontal therapy with pulpal involvement. Regardless the pathology has an endodontic and/or a periodontal origin, the periodontal tissues are attacked, and their healing depends on the establishment of an accurate diagnosis and an appropriate therapy.

Thus, the use of a systematic diagnostic process will help in the identification and treatment of endodontic-periodontal lesions. This article presents successful healing of endo-perio lesion after non-surgical endodontic treatment.

Methods: Two cases are presented where a true combined endodontic-periodontal lesion was diagnosed. The treatment included the root canal treatment and subsequent scaling and root planing.

Results: The periapical lesions were significantly reduced six months after the treatment.

Conclusion: Periodontal-endodontic lesions are complex in nature and have various pathogenesis. The long-term prognosis after treatment of perio-endo lesions is determined by correct primary diagnosis and careful endodontic treatment, followed by periodontal treatment if necessary.

Keywords:

endodontic-periodontal lesion – root canal treatment – periapical radiolucency – furcation defect

INTRODUCTION

Endodontic-periodontal lesion is a clinical manifestation of the pathologic/inflammatory inter-communication between the pulpal and periodontal tissues via open structures such as apical foramina, lateral and accessory canals [1]. It is one of the common problems associated with the tooth. In 1964, Simring and Goldberg first described the true relationship between the periodontal and pulpal disease. The most common connection between these tissues is the apical foramen. Through the apical foramen, an infection of the endodontium can cause periapical and periodontal lesions. Conversely, periodontitis with deep pockets reaching the tooth apex can result in an infection of the pulpal tissues [2]. However, connections between the periodontium and endodontium may also exist via the formation of non-physiological pathways, known as iatrogenic endodontic-periodontal lesions [3]. The diagnosis of an endodontic-periodontal lesion is complex because a single lesion may present signs of endodontic and periodontal involvement. This suggests that one disease may be the result or cause of the other or even originate from two different and independent processes, which are associated by their advancement. However, identifying the ethiology of these combined lesions as well as the existence of several available classifications are still problematic. Clinicians are, therefore, still faced with diagnostic difficulties, which may lead to treatment failure as well as healing delay. The differential diagnosis of endodontic and periodontal diseases can sometimes be difficult, but it is of vital importance to make a correct diagnosis so that the appropriate treatment can be provided. A good prognosis for combined endo-perio lesions may be obtained by endodontic and periodontal therapy. However, when a significant loss of the periodontal attachment apparatus and osseous structure occurs, the long-term prognosis becomes poor [4].

The aim of this article is to show two case reports with a non-surgical management of endo-perio lesion with a six-months follow up.

Case 1

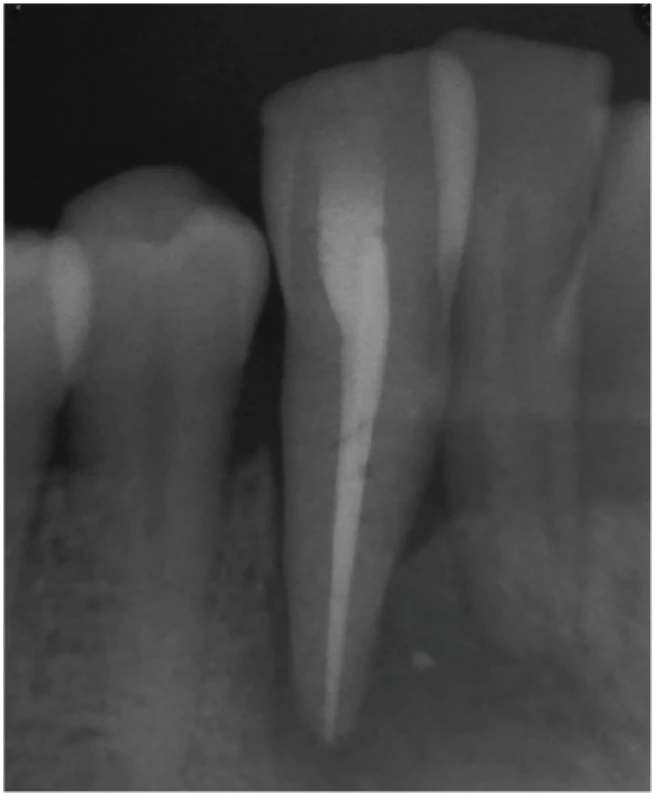

A 35-year-old female patient came to the Department of Restorative Dentistry and Endodontics of the Dental clinic of Monastir with mobile lower right canine (tooth no. 43) with uncomfortable bite in the same area. The medical history was insignificant. She had a history of trauma on the lower lip and teeth when she was 10 years old. She did not receive dental treatment at that time. The clinical examination revealed a sinus tract seen related to tooth 43 with grade II mobility and 7 mm deep periodontal pocket along the mesiolingual surface. The tooth did not respond to pulp sensitivity test (Pharmaéthyl, Septodont Lancaster PA 17901, USA) and was slightly tender to percussion. Radiographic examination revealed pathologic radiolucency around the apex of tooth 43, severe bone loss between teeth 42 and 43 and dental calculus on roots of teeth 41 - 43 (Fig. 1). Based on clinical and radiographic findings, the lesion was diagnosed as a true combined lesion according to Simon classification.

1. Periapical radiograph of tooth 43

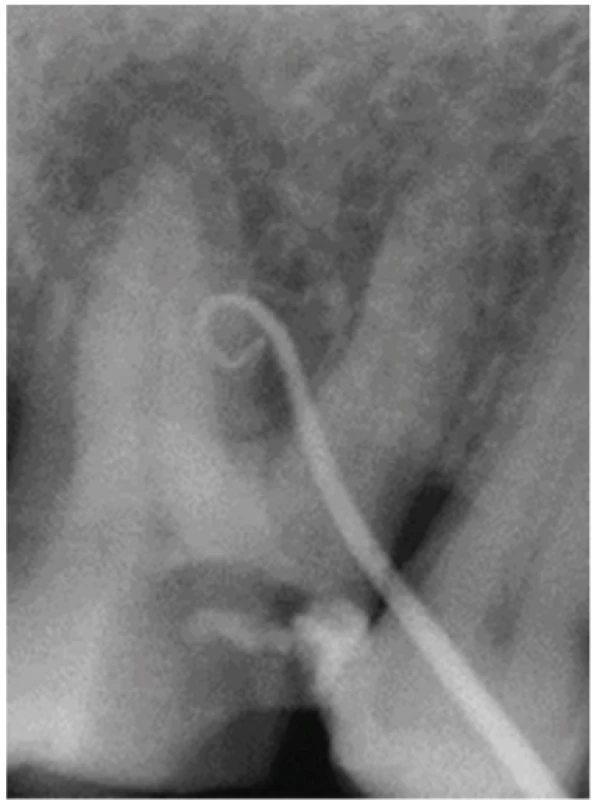

Root canal treatment with initial scaling and root planing were simultaneously performed during disease control phase. Under rubber dam and without local anesthesia, the canal was cleaned and shaped by using stainless steel files (Fig. 2) and nickel-titanium rotary instruments (2Shape, Micro Mega® 25000 Besancon, Francie). The canal was irrigated with 3% sodium hypochlorite. The canal was dried with paper points and filled with calcium hydroxide (UltraCalTMXS, Ultradent ESPE Products, INC, Dr. South Jordans, UT 84095, USA). The access cavity was sealed with a temporary filling material (CavitTM W, 3M ESPE Deutschland GmbH, Seefeld, SRN).

After two weeks the patient reported no more pain and she felt much better. The tooth 43 was reaccessed, calcium hydroxide was removed, and the canal was irrigated with 3% sodium hypochlorite and 17% EDTA. Canal obturation was completed using warm vertical compaction of gutta percha (System B, Sybronendo; 2shape GP Points, Micro Mega®) with resin-based root canal sealer (AH PlusTM, Dentsply Sirona,

Stonhouse. Gloucestershire, Vel. Británie) (Fig. 3 and 4). Access cavity was sealed with composite resin (Filtek Z350XT, 3M ESPE).

The patient was seen six months after the treatment to evaluate tissue healing and tooth mobility. She was asymptomatic with no pain on biting. A periapical radiograph showed a significant reduction in the size of the periapical radiolucency (Fig. 5). Clinically, no mobility or periodontal pocket was detected.

5. Check-up radiograph after 6 months

Case 2

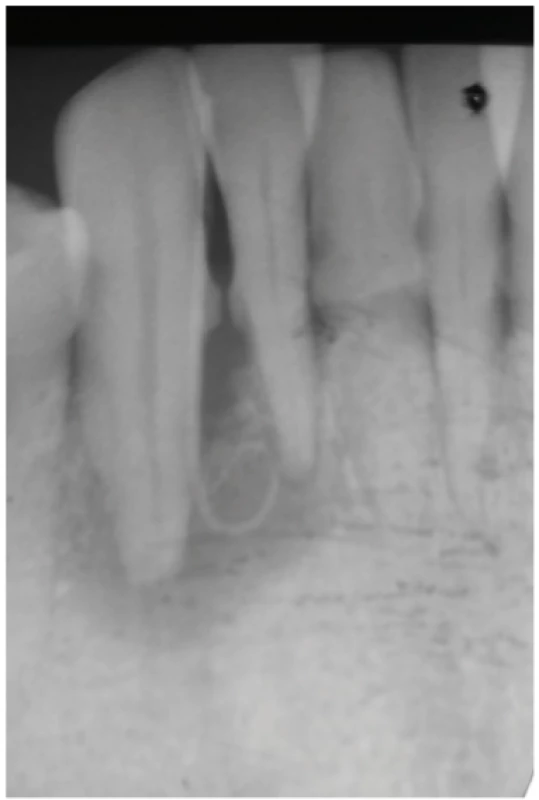

A 40-years-old female patient came to the Department of Restortive Dentistry and Endodontics of the Dental Clinic of Monastir with pain and pus outflow from right maxillary first molar (tooth no. 16) (Fig. 6). Intra oral examination revealed mesioocclusal caries of tooth 16 with no the response to pulp test (Pharmaéthyl, Septodont), and a productive fistula. The tooth was slightly tender to percussion. Periodontal probing depth was 5 mm on distal aspect of tooth 16 and there was no mobility. A periapical radiograph showed pathologic radiolucency around the apices of the palatal, mesiobuccal and distobuccal roots, and also bone resorption mesially, distally and interradicularly (Fig. 7). Based on clinical and radiographic findings, the lesion was diagnosed as true combined lesion, according to Simon’s classification.

6. Intra oral view on tooth 16

The tooth was isolated with rubber dam, the caries was excavated, and the access cavity was prepared with endodontic access bur; without any local anesthesia. Three canal orifices were located. Working length was determined by electronic apex locator and was confirmed radiographically with ISO 15 K-files. Cleaning and shaping were carried out using rotary system (2Shape, Micro Mega®) in adjunct with copious irrigation with 3% sodium hypochlorite solution. After chemo-mechanical preparation of canals a non-setting calcium hydroxide paste (Metapex, Meta Biomed®) was dispensed into the canals and temporary restoration was placed.

Follow up was done after three weeks. The patient was asymptomatic, root canals were obturated with zinc oxide eugenol sealer (Pulp Canal Sealer™ EWT, Kerr) and gutta percha points (2shape GP Points, Micro Mega®) using the lateral condensation technique. The coronal seal was performed using composite resin (Filtek Z350XT, 3M ESPE). At the same time scaling and root planning was carried out to improve healing.

Six months after the treatment, the radiographic examination revealed a regression of the periapical lesion (Fig. 8).

8. Check-up radiograph after 6 months

DISCUSSION

Endo-perio lesions present challenges to clinicians, as diagnosis and prognosis of the involved teeth are of concern. Correct diagnosis is an essential prerequisite to select a suitable treatment modality to ensure a good long-term prognosis. Treatment decision making and prognosis depend primarily on the diagnosis of the specific endodontic and/or periodontal disease. The main factors to consider are pulp vitality and periodontal disease type. However, pulp tests may not always be reliable. This consideration is particularly relevant when challenges to pulpal status arise from periodontal diseases such as partial necrosis of the pulp in a multirooted tooth due to long-term periodontal lesions. The presence of severe pain associated with a periodontal lesion can be the result of acute dentoalveolar abscess or pulp degeneration [5]. Through radiographic examinations, the presence of bone loss, presence and depth of restorations and endodontic treatments can be evaluated. The presence of bone rarefaction at the furcation region showing the proximal bone crests preserved indicates that the lesion is of an endodontic and not of a periodontal origin, as well as marginal bone loss with apical rarefaction, which has or has not undergone endodontic treatment. If there is a deeper and more angulated marginal bone loss in a single tooth with normal apical contour of the periodontal ligament without presenting aggression factors to the pulp, the periodontal disease may occur over the pulp [6].

The true combined lesions take place when the pulp necrosis and periodontal disease are within a same tooth, occurring together or alone. The diagnosis of such lesions is more complex than for those cases with either isolated periodontal disease or periapical lesion [7].

Combined lesions can be classified into three types, namely: (i) teeth with two separate lesions, one endodontic (usually periapical) and one periodontal, with no communication; (ii) teeth with a single lesion that involves both endodontic and periodontal pathoses; and (iii) teeth with endodontic and periodontal lesions that were once separate but now communicate.

True combined endodontic‑periodontal lesions, as in both our cases, require both endodontic and periodontal treatment procedures. The authors recommend primarily the treatment of the endodontic lesion, followed by non-surgical periodontal therapy. During the root canal treatment the canals an intracanal medication (calcium hydroxide) should be placed [8]. Finishing of endodontic treatment before periodontal intervention has been advocated, since the presence of bacteria in the root canal system may affect the outcome of the periodontal treatment and hinder healing of pocket due to the endodontic component. Prior to any surgery, initial periodontal therapy should be performed, and root canal treatment carried out. The prognosis of a true combined lesion is often poor or even hopeless, especially when periodontal lesions are chronic and extensive.

The possible influence of endodontic treatment on the healing response of furcation defects is related to the accessory canals and permeable areas of dentin and cementum. Accessory canals in the whole furcation area of molars are found in 30–60% of molars and predispose this area to be a zone of intense communication between pulpal and periodontal tissues. Healing of the periodontal tissues occurs after endodontic treatment as it was observed in case two. The periodontal healing is evaluated after 3 or 4 weeks. Endodontic treatment is highly predictable when appropriately performed. The achievement of a hermetic seal is often cited as a major goal of root canal treatment. However, effective endodontic therapy must be combined with scaling and root planing in cases of true combined lesions and primarily periodontal lesins. According to Vanchit et al. [9], among some surgical approaches, the guided tissue regeneration can be used in which a membrane prevents the migration of the epithelial cells towards the defect during the healing. The grafting material can be autogenous, allogenous or alloplastic [10].

The success rate of the endodontic‑periodontal combined lesion without a concomitant regenerative procedure has been reported to range from 27% to 37% [11].

CONCLUSION

Endo perio lesions present challenges to the clinicians as regards their proper diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. It has a complex pathogenesis and requires great skill to identify and treat. Cooperation between different disciplines that includes periodontology, endodontic and prosthodontics is required to effectively treat these lesions.

Corresponding author

Assistant professor Dr Emna Hidoussi

Department of Restorative Dentistry-Endodontics, Faculty of Dental Medicine

Resid Mourabitine. App 115 Ribat 5, Monastir

Tunisia

e-mail :.minoumd@gmail.com

Sources

1. Priyanka MG, Jaiganesh R. Endo perio lesion. A case report. J Med Biomed App Sci. 2017; 5(2): 108–110.

2. Nair PN. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004; 15(6): 348–381.

3. Rotstein I, Simon JH. Diagnosis, prognosis and decision making in the treatment of combined periodontal-endodontic lesions. Periodontology. 2004; 34 : 165–203.

4. Priya SA, Chakraborty A, Sananda S. Endodontic periodontal lesion: A two-way traffic. Inter J applied Dent Sci. 2018; 4(4): 223–228.

5. Carmen MS, Giuliana MB, Tarcisio TP. How to diagnose and treat periodontal endodontic lesions? RSBO. 2012; 9(4): 427–433.

6. Hacer A, Ahmet S. A case series associated with different kinds of endo-perio lesions. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014; 6(1): 91–95.

7. Shenoy N, Shenoy A. Endo-perio lesions: Diagnosis and clinical considerations. Indian J Dent Res. 2010; 21 : 579–585.

8. Schacher B, Haueisen H, Ratka-Krüger P. The chicken or the egg? Periodontal-endodontic lesions. Periodont Pract Today. 2007; 4(1): 15–21.

9. John V, Warner NA, Blanchard SB. Periodontal endodontic interdisciplinary treatment: A case report. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2004; 25 : 601–604.

10. Von Arx T, Cochran DL. Rationale for the application of the GTR principle using a barrier membrane in endodontic surgery: A proposal of classification and literature review. Int J Periodont Restorative Dent. 2010; 21 : 127–139.

11. Parolia A, Gait TC, Porto IC, Mala K. Endo-perio lesion: A dilemma from 19th until 21st Century. J Interdiscip Dentistry. 2013; 13(1): 2–11.

12. Nanavati B, Bhavsar NV, Mali J. Endo periodontal lesion – a case report. J Adv Oral Res. 2013; 4(1): 23–27.

13. Zehnder M, Gold SI, Hasselgren G. Pathologic interactions in pulpal and periodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol. 2002; 29(8): 663–671.

14. Bansal S, Tewari S, Tewari S, Sangwan P. The effect of endodontic treatment using different intracanal medicaments on periodontal attachment level in concurrent endodontic-periodontal lesions: A randomized controlled trial. J Conserv Dent. 2018; 21(4): 413–418.

Labels

Maxillofacial surgery Orthodontics Dental medicine

Article was published inCzech Dental Journal

2020 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Editorial

- International association of paediatric dentistry (iapd) – 50. Výročí založení

- A clinical, radiographic and histologic observation of human immature permanent tooth after failed revitalization treatment and subsequent root canal treatment

- Stability of orthognatic surgery in cleft lip and palate patients

- Healing of endodontic periodontal lesion after non-surgical treatment

- Vagueness and Exactiveness in class II, division 2 diagnostics

- Stomatologie v éře COVID-19

- Doporučená ochrana před přenosem virových infekčních onemocnění v době epidemií, nyní zejména SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19

- Early Childhood Caries: IAPD Bangkok Declaration

- Czech Dental Journal

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Healing of endodontic periodontal lesion after non-surgical treatment

- Stability of orthognatic surgery in cleft lip and palate patients

- Doporučená ochrana před přenosem virových infekčních onemocnění v době epidemií, nyní zejména SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19

- Vagueness and Exactiveness in class II, division 2 diagnostics

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career