-

Medical journals

- Career

A conceptual ideal supraglottic airway

Authors: Miller M. Donald

Authors‘ workplace: Guys Hospital, London, UK

Published in: Anest. intenziv. Med., 22, 2011, č. 3, s. 149-152

Category: Anesthesiology - Review Article

Overview

The single most important factor motivating research and development of SGAs is the associated risks of intubating patients with a tracheal tube. Predictable airway injury and the greater side-effects in the use of tracheal tubes is putting pressure on favouring SGAs over tracheal tube anaesthesia. In the future, the ability to minimize side-effects while obtaining better quality of seal in an SGA may determine the extent to which tracheal tube anaesthesia becomes a practise that will be limited to patients with full stomachs and special requirements such as thoracic anaesthesia.

The factors that influence safety as well as the various compromises that have to be made with respect to each characteristic of the various designs of supraglottic airway are discussed and quantified. These factors include quality of seal, ease of insertion, side-effects in their use, aspiration protection/access to the gastrointestinal tract and suitability for use in difficult airway scenarios. A scoring system may help us assess newer devices against what we currently have available to us and provide a more objective basis to measure or compare the various devices.Keywords:

supraglottic airway device – seal pressure – aspiration – positive pressure ventilationIntroduction

A variety of approaches to SGAs may be taken. For the sake of simplicity, sealing site is quite useful in that it does make sense that if there is failure to seal using one type of SGA, better success is more likely if one with a different sealing site is chosen.

Proposed simple classification is:

- a) Peri-laryngeal sealing

- aa) Simple – LMAc, LMAu

- ab) Wedge cuff – iGel, LMA Supreme

- ac) Directional seal – LMA ProSeal

- ad) Lever assisted – iLMA.

- b) Base of tongue sealing

- ba) with oesophageal cuff – Combitube, LT, LTS, LTSd

- bb) without oesophageal cuff – COBRA PLA

- bc) pre-shaped pharyngeal liner – SLIPA

Why should we aspire to developing an “ideal supraglottic airway”?

Factors motivating future development of SADs relate to the recorded actual and potential damage in the use of tracheal tubes during routine anaesthesia.

The first fact of note is that after every case where tracheal tubes were used, there was an increase in resistance to airflow compared to when a supraglottic airway had been used [1].

This increase in resistance is attributed to swelling of laryngeal soft tissues. An editorial in the same journal concluded that, “Based on the available information, one can reasonably conclude that even routine tracheal intubation significantly affects the larynx anatomically and functionally”[2].

Consistent with this finding is a more recent study [3] which included over 3000 routine cases that were intubated. Figure 1 is graphical redraw with a linear time scale of the findings in this study. This graphical display shows that there is a predictable injury profile with intubation. The incidence of 1 per 1000 cases with permanent hoarseness associated with arytenoid dislocation is quite an alarming figure.

Fig. 1. The incidence of hoarseness following tracheal intubation

These finding are consistent with the findings of Domino et al. who showed that routine patients contributed 4 times the number of closed claims for serious laryngeal injury compared with management of difficult airways patients. This is despite the fact that patients with known difficult airways have 4.53 times the risk of for serious laryngeal injury. It is stating the obvious to say that this is because the routine patient is much more common than the difficult airway patient [4].

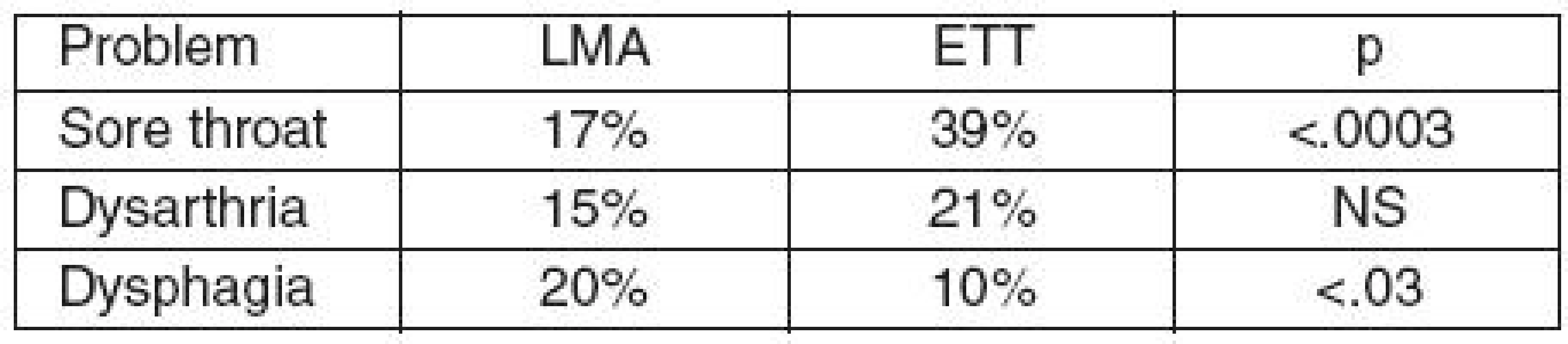

An extensive metanalysis study involving two independent reviewers of 29 randomized prospective controlled trials – predetermined selection criteria, compared tracheal tube anaesthesia with anaesthesia using a laryngeal mask [5]. The findings are summarised in the table 1.

1. Meta-analysis comparing the complications associated with the endotracheal tube vs. laryngeal mask airway [5] ![Meta-analysis comparing the complications associated with the endotracheal tube vs. laryngeal mask airway [5]](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/bf4192aeab74d057694f31bd8392e2a3.jpeg)

These findings are consistent with the findings of Brimacombe [6] in 2005 who showed the difference in the following table 2.

2. Complications associated with the endotracheal intubation vs. the laryngeal mask airway

We are forced to conclude that the tendency to prefer to administer anaesthesia with a supraglottic airway is well founded on the available evidence. Nevertheless, that is merely to look at one side of the picture. There are also serious side-effects using SGAs. Brimacombe showed that up until 2005, there had been ten published/reported cases of recurrent laryngeal neuropraxias, four hypoglossal, and five lingual neuropraxias [7].

The occurrence is fortunately rare, however, the incidence must exceed the published incidence by some margin. Many more have been reported since and many have not been reported. So although the evidence favours the use of a SGAs in preference to a tracheal tube, it is still not free from the associated risk of serious side-effects.

Improvement in seal quality without the associated increase or preferably with a decrease in the risk of pressure damage to these vulnerable nerves in the pharynx is the future direction that we need to take in the development of SGAs.

In this regard there does appear to be a new device called the Baska airway with a cuff that is inflated by the airway pressure [7]. It supposedly has excellent aspiration protection mechanisms also. This dynamic seal would appear to be the direction that future developments should take, if we are to achieve the stated objective. That is to develop the kind of supraglottic airway that will seal better than what we have today but with less risk of nerve injury or aspiration. Unfortunately, there are no published reports of its use in patients thus far. Such a device could further limit the use of tracheal tubes for routine use in the future.

How are we going to compare and assess old and new SGAs?

There is no such thing as an ideal supraglottic airway. Nevertheless, it is a good exercise to imagine the ideal. It will focus priorities as to what to look for in a supraglottic airway. The two most prominent airway manufacturers for the European markets appear to be Intavent and Ambu. Both manufacturers have opted to give us a whole range of products for different applications. The imagined objective is to not compromise in the quality of delivery. All devices involve the balancing of features and compromises. Different circumstances will indicate which of the priorities is most desirable. We need to ask, which of the desirable qualities do we most frequently depend on? Also related to safety is the question how helpful is having a combination of desirable qualities in one device? These two questions both consider the priority of safety looking at two differing but potentially competing aspects. That raises a third question as to what is gained and what is compromised? An attempt to try and quantify these complex interactive factors is made.

To relate these questions to specific situations will enhance the appreciation of the value of asking these questions. Higher seal pressures might be associated with a higher incidence of pressure damage. To incorporate intubation characteristics in the device might compromise on comfort and ease of insertion. So Intavent manufacture LMA Supreme that is really not good for accessing the trachea but Intavent decided that an LMA with a better seal, ease of insertion, and access to the stomach and protection from regurgitation were a higher priority. If you want to intubate a patient through the LMA, you should use an ILMA [6]. The ILMA is an airway that has good seal characteristics and excellent intubating characteristics. The compromises involved in the use of the device are an increase in sore throats and sometimes difficulty with insertion. In addition, they are more expensive than standard LMA devices. Nevertheless, it is not out of the question to consider the device for routine use. However, the intubating characteristics are rarely needed. Price and sore throats are the main consideration here [8].

The i-gel is a device that is generally very easy to insert and gives a nice clear airway. However, the compromises associated with its use are the occasional low seal pressure, and although it has a gastric tube, it is not entirely risk free of aspiration with reflux because of a poor seal at the cricopharyngeus level. In the event of regurgitation, it may be marginally safer than the standard LMA from an aspiration risk point of view. The gastric tube does allow for air to escape from the oesophagus, so there is less risk of gastroesophageal insufflation than with LMA during IPPV.

The fact that it has no cuff inflating mechanism may contribute to less risk of nerve damage that has been recorded occasionally with LMA. However, the injury rate appears to be too rare to feature as a consideration of importance in most people’s estimates [9].

Scoring of the SADs quality

The author’s view of SGA characteristics are:

- A) What are the most important and fundamental essential requirements in a supraglottic airway:

- Good quality seal pressure without the risk of pressure damage to recurrent laryngeal or hypoglossal nerves.

- A consistently clear reliable airway without airflow obstruction.

- Minimal risk of trauma/damage/side-effects e.g. sore throat, hoarseness, dysphagia.

- B) Highly desirable characteristics include:

- Effective aspiration protection mechanism or mechanisms, with effectiveness being more important than the number of mechanisms.

- A means of access to the oesophagus from the point of view of surgical requirements (laparoscopic work) or monitoring requirements (oesophageal doppler).

- Alternative means of handling difficult airways – such as easy intubation or ease of access to the trachea with optical devices.

The authors personal view puts a weighting on the importance of each characteristic:

A1–6 points

A2–3

A3–3

B1–4

B2–1

B3–4Total maximum score would be 21. A theoretical perfect SGA would score 21 – table 3.

3. Information for completing these scores is based upon the following references [8–11]* ![Information for completing these scores is based upon the following references [8–11]*](https://www.prolekare.cz/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/9982f44efda14215061d2f3f0932308a.jpeg)

*Plus some theoretical considerations e. g. for Baska airway. Conflict of interest: Donald M. Miller has a financial interest in the development of the SLIPA.

Došlo dne 30. 3. 2011.Přijato dne 10. 4. 2011.

Correspondence:

Dr Donald M. Miller, MB,ChB; FFA(SA); PhD(Stell).

Consultant Anaesthetist

Guys Hospital, Great Maze Point

SE1 9RT, London, UK

E-mail: donald.miller@kcl.ac.uk

Sources

1. Tanaka, A. et al. Laryngeal resistance before and after minor surgery: endotracheal tube versus Laryngeal Mask Airway. Anesthesiology, 2003, 99, p. 252–258.

2. Mazen, A. et al. Is Routine Endotracheal Intubation as Safe as We think or Wish? Anesthesiology, 2003, 99, p. 247–248.

3. Yamanaka, H. et al. Prolonged hoarseness and arytenoid cartilage dislocation after tracheal intubation. Brit. J. Anaesthesia, 2009, 103, 3, p. 452–455.

4. Domino, K. B. et al. Airway injury during anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology, 1999, 91, p. 1703–1711.

5. Yu, S. H., Beirne, O. R. Laryngeal mask airways have a lower risk of airway complications compared with endotracheal intubation: a systematic review. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg., 2010, 68, p. 2359–2376.

6. Brimacombe, J. Laryngeal Mask Anaesthesia. 2nd Edition, WB Sanders: Philadelphia 2005, p. 555–556, 563, 140.

7. www.proactmedical.com.au

8. Gerstein, N. S., Braude, D. A., Hung, O., Saunders, J. C., Murphy, M. F. The Fastrach intubating laryngeal mask airway: an overview, an update. Can. J. Anaesth., 2010, 57, p. 588–601.

9. Theiler, L. G., Kleine-Brueggeney, M., Kaiser, D., Urwyler, N., Luyet, C., Vogt, A., Grief, R., Unibe, A. Crossover comparison of the laryngeal mask Supreme™ and the i-gel™ in simulated difficult airway secenario in anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology, 2009, 111, p. 55–62.

10. Miller, D. M., Light, D. Laboratory and clinical comparisons ofthe streamlined liner of the pharynx airway (SLIPA) with the laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia, 2003, 58, p. 136–142.

11. Miller, D. M. A proposed classification and scoring system for supraglottic sealing airways: a brief review. Anesth. Analg., 2004, 99, p. 1553–1559.

Labels

Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Inten Intensive Care Medicine

Article was published inAnaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine

2011 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Pitfalls of postoperative care following carotid artery surgery

- Serotonine syndrome – Case report

- Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness

-

Zajištění dýchacích cest – souhrny přednášek

Praha 11. 11. 2010 - Premedication with etoricoxib before tonsillectomy

- Intraosseous access to the vascular system for orthotopic liver transplantation

- A conceptual ideal supraglottic airway

- Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness

- Serotonine syndrome – Case report

-

Zajištění dýchacích cest – souhrny přednášek

Praha 11. 11. 2010 - Pitfalls of postoperative care following carotid artery surgery

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career