-

Medical journals

- Career

Characteristics of fingertip injuries and proposal of a treatment algorithm from a hand surgery referral center in Mexico City

Authors: Telich-Tarriba E. J.; Santos-Gallegos I.; Arroyo-Berezowsky C.; Cardenas-Mejia A.

Authors‘ workplace: Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Division, Hospital General “Dr Manuel Gea Gonzalez”, Postgraduate Division of the Medical School, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico 1; Universidad de las Americas Puebla School of Medicine, Puebla City, Mexico 2; Center for Orthopedics and Traumatology, Centro Medico ABC, Mexico City, Mexico 3

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 63, 3, 2021, pp. 113-117

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp2021113Background

Fingertips are the most commonly injured anatomical structures of the upper extremity. Their distal location, wide range of movement, and lack of protective structures make them prone to accidents [1]. Over 3 mil. cases are reported annually in the United States [2]. Information regarding their incidence and prevalence in Mexico is lacking, but suspected to be high.

The fingertips are specialized structures that contribute to fine motor control and tactile sensation, they also possess an esthetic value despite their small size. Although fingertip injuries do not represent a risk to a patient’s life, adequate evaluation and management are necessary to avoid the development of chronic pain, disability, limitation of social and work activities, or psychological stress [3,4].

Management strategies for fingertip injuries are still debated. International literature is comprised mainly by retrospective, non-comparative studies that present a wide range of recommendations: from coverage with semi-occlusive dressings to supermicrosurgical replantation [5].

Most of the published information comes from developed countries, therefore some treatment strategies do not adjust well to the economic capabilities or sociocultural values of developing nations [6]. Despite this, reconstructive strategies in this group of patients should focus in obtaining a stable skin envelope, minimization of pain, optimization of healing time, preservation of sensitivity and length, prevention of painful neuromas, avoidance of nail deformity, decrease in time lost from work, and providing an acceptable cosmetic appearance [2].

The “Dr Manuel Gea Gonzalez” General Hospital is a tertiary medical facility that provides care mostly to low-income uninsured patients of the southern and eastern areas of Mexico City, amounting to a target population of 2.5 mil. people. It is also recognized as a national referral center for plastic and hand surgery [7]. The aim of this work is to present our experience in the management of fingertip injuries.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study was performed to identify the prevalence of fingertip injuries and their treatment strategies. Data was obtained using written and photographic records from the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Department of the “Dr Manuel Gea Gonzalez” General Hospital in Mexico City.

Every patient with a fingertip injury, defined as any form of trauma affecting the portion of the finger distal to the insertion of the flexor digitorum superficialis and extensor tendons on the distal phalanx, or the interphalangeal joint when referring to the thumb, managed by a plastic surgeon in the emergency department between July 2010 and June 2015 was included in the study.

Full approval by the institutional ethics board was received. Consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians prior to any procedures, and all procedures were in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Information was recorded using a data sheet including the following information: patients' demographic characteristics, anatomical location of the lesion (finger, right or left side affected), type of injury (laceration, amputation or nail-bed injury), and type of treatment (conservative or surgical).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses of patient demographic and clinical characteristics were performed. Continuous variables are expressed in central tendency measures, and categorical values are presented as percentages.

Results

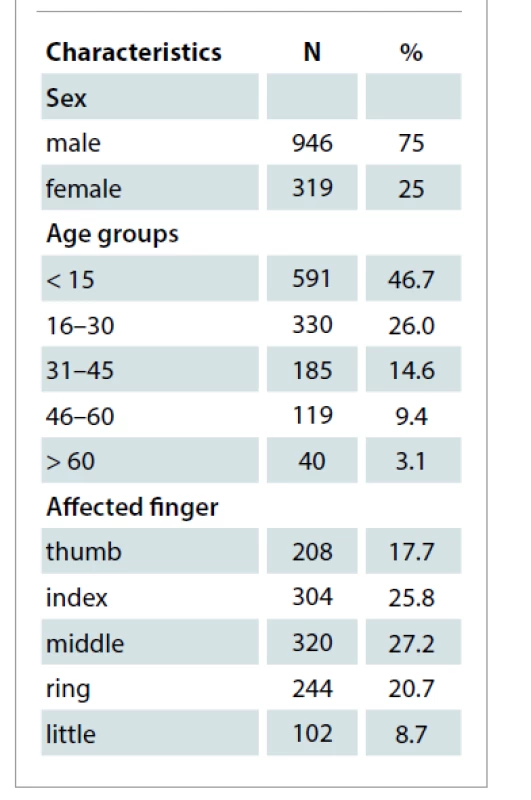

During the 5-year period, a total of 1,265 patients presented with fingertip injuries. Seventy-five percent of the patients were males, resulting in a male-to-female ratio of 3 : 1. Mean age of presentation was 20.5 ± 16.46 years. Subsequently, age distribution was classified into 5 groups: 591 patients (46.7%) were younger than 15 years, 330 (26.0%) patients were 16–30 years, 185 (14.6%) were 31–45 years, 119 (9.4%) were 46–60 years, and 40 (3.1%) were older than 61 years of age. Right and left-sided injuries were almost equally prevalent (51 vs. 49%). The most commonly injured finger was the middle (27.2%), followed by the index finger (25.8%), the ring finger (20.7%), the thumb (17.7%) and the small finger (8.7%). Eighty-seven percent of the patients presented with single-digit injuries, 10.7% had injuries in two fingers, and the rest had lesions in three or more digits (Tab. 1).

1. Demographic characteristics of the population.

Fingertip amputations were the most common type of injury with 620 cases (49%), followed by simple fingertip lacerations (574 cases, 45%), and nail bed injuries in 71 cases (5.6%). Seventy-six patients (6%) suffered from distal phalanx fractures, evidenced by X-ray imaging. Ninety-five percent of the patients required invasive procedures, 99.5% were performed under local anesthesia in a specialized operating room in the emergency department, while the remaining cases were hospitalized and operated in the main operating theaters under general or regional anesthesia.

Allen’s classification was used for fingertip amputation. Type 3 lesions were the most prevalent (35.6%), closely followed by type 2 (33.1%), types 1 (17.6%) and 4 (13.7%). Most cases were managed by primary closure (370 patients, 59.6%), 188 patients (15%) required homodigital advancement flaps, regional flaps were performed in 31 patients (5%) and healing by secondary intention was indicated in 28 cases (4.5%). No fingertip replantation was attempted in this series.

Fingertip lacerations were managed by simple primary closure in 192 cases (33.5%), primary closure and nail bed repair in 367 patients (63.9%) and healing by secondary intention in the remaining cases (2.6%).

Simple nail-bed injuries were repaired in 62 cases (86.1%), and managed conservatively in 9 patients (12.6%). Distal phalanx fractures were reduced and fixed with a K-wire in 62 cases (81.5%), all other cases were managed conservatively (14, 18.4%) (Tab. 2).

2. Frequency of each type of injury, and treatment strategies applied.

Discussion

Fingertips are critical structures for hand function, specially fine motor control and sensitivity. Therefore it is important for plastic, orthopedic and hand surgeons to be familiar with the reconstructive strategies developed for this anatomical structures. Fingertip injuries are a frequent cause of consultation in emergency departments. In our study, similar to other published series, fingertip injuries are the most common type of upper extremity trauma [8].

To this day, there is a considerable debate regarding optimal management of fingertip injuries. Few management recommendations are evidence-based, and there is a lack of prospective, comparative trials to guide treatment [5]. Several factors must be considered prior to selecting any treatment modality, such as trauma mechanism, wound geometry and size, patient’s age, comorbidities and occupation. Nevertheless, reconstructive goals should focus in obtaining stable skin coverage, optimization of healing time, preservation of sensitivity and length, prevention of painful neuromas, avoiding or limiting nail deformity, minimizing time lost from work, and providing an acceptable cosmetic appearance [1,9].

The male-to-female ratio in our population was 3 : 1, these results are similar to other reports, and may reflect the predominance of male workers involved in manufacturing and service jobs in emerging economies [10]. Unlike what is seen in global upper extremity trauma, where economically active people are the largest affected group, almost half of all fingertip injuries were seen in minors. This is relevant due to the added complexity that results from operating smaller structures in potentially uncooperative patients, and the degree of physical and economical burden the development of disability can cause for the patients or their families [7].

Most of our patients were treated using simple surgical procedures such as primary closure or local flap advancement. An incentive for this conduct stems from the fact that our patients tend to be uninsured manual laborers with low-income. Therefore they often ask for a quick return to work and tend to reject procedures requiring hospitalization, such as complex flaps or replantation.

Although replantation seems an ideal method for the treatment of fingertip amputation it is not routinely performed in the Americas, as opposed to Asian countries. Some reasons for this include the risk for replantation failure, need for skillful microsurgical technique, long intraoperative time, prolonged hospital stay, longer time off from work, and higher costs [11–13].

Recent evidence has come to question whether complex reconstructive procedures are worth the time, expense, and risk. For example Wang et al found no outcome differences when comparing complex reconstructions to bone shortening and primary closure, or secondary healing. Meanwhile a survey study by Miller et al found that wound care, stump remodeling or flap advancement were the preferred treatment options by US and international hand surgeons [5,14,15], mirroring our results.

A structured approach to fingertip reconstruction greatly improves management, specially in academic centers. In 2008 Lemmon et al [16] proposed a treatment algorithm based on characteristics of the injury and the digit affected. We further simplified this algorithm to rely in basic procedures like local and regional random flaps, making it accessible to surgeons of varying levels of skill and knowledge (Scheme 1). This algorithm also fits the sociocultural needs of our patients allowing for quick recovery and minimal downtime. We strongly believe that our results can be applied to other urban areas internationally, especially in developing nations with similar health systems as ours.

Scheme 1. Proposed algorithm for the management of fingertip injuries [16]. ![Scheme 1. Proposed algorithm for the management of fingertip injuries [16].](https://pl-master.mdcdn.cz/media/image_pdf/7fce7f8e5d5fe63ad9d9b79afe588a4a.png?version=1636275438)

FDMA – first dorsal metacarpal artery Despite our results, it should be taken into account that several interventions in the reconstructive armamentarium remain valuable, and in some cases may deliver better results in aspects like sensitivity, such as regional neurovascularized flaps. Surgeons should proceed with reconstruction only after a thoughtful discussion with the patient and then perform the procedure with which he or she is most comfortable.

The main limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and lack of long-term outcome reports. However, it represents the first step in establishing an epidemiological and demographic registry of fingertip patterns of injury and their management in Mexico.

Conclusions

Fingertip injuries remain the most common reason for consultation in hand emergencies. Even though most cases can be adequately solved by primary closure it is important that the reconstructive team in charge of these patients follow a structured approach for their treatment and is familiar with the several treatment strategies available, in order to obtain the best clinical outcomes.

Role of authors: All authors have been actively involved in the planning, preparation, analysis and interpretation of the findings, enactment and processing of the article with the same contribution.

Disclosure: The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Sources of funding: None declared.

José E. Telich-Tarriba, MD

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Division

Hospital General “Dr. Manuel Gea Gonzalez”

Av. Calzada de Tlalpan 4800

Tlalpan, Mexico city, 14080

Mexico

e-mail: josetelich@gmail.com

Submitted: 27. 4. 2021

Accepted: 24. 7. 2021

Sources

1. Peterson SL., Peterson EL., Wheatley MJ. Management of fingertip amputations. J Hand Surg Am. 2014, 39(10): 2093–2101.

2. Weichman KE., Wilson SC., Samra F., et al. Treatment and outcomes of fingertip injuries at a large metropolitan public hospital. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013, 131(1): 107–112.

3. Gonzalez C., San-Miguel R. Lesiones traumáticas de la mano. Estudio epidemiológico. Rev Mex Ortop Traum. 2001, 15(5): 230–234.

4. Hacıkerim Karşıdağ S., Ozkaya O., Uğurlu K., et al. The practice of plastic surgery in emergency trauma surgery: a retrospective glance at 10,732 patients. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011, 17(1): 33–40.

5. Miller AJ., Rivlin M., Kirkpatrick W., et al. Fingertip amputation treatment: a survey study. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015, 44(9): E331–E339.

6. Torres-Fuentes CE., Hernandez-Beltran JA., Castañeda-Hernandez DA. Manejo inicial de las lesiones de punta de dedo: guía de tratamiento basado en la experiencia en el Hospital San José. Rev Fac Med. 2014, 62(3): 335–363.

7. Telich-Tarriba JE., Velazquez E., Theurel-Cuevas A., et al. Upper extremity patterns of injury and management at a Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Referral Center in Mexico City. Ann Plast Surg. 2018, 80(1): 23–26.

8. Sorock GS., Lombardi DA., Hauser RB., et al. Acute traumatic occupational hand injuries: type, location, and severity. J Occup Environ Med. 2002, 44(4): 345–351.

9. Germann G., Rudolf KD., Levin SL., et al. Fingertip and thumb tip wounds: changing algorithms for sensation, aesthetics, and function. J Hand Surg Am. 2017, 42(4): 274–284.

10. Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática. Indicadores de ocupación y empleo al cuarto trimestre de 2016 [online]. Available from: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/temas/default.aspx?s=est&c=25433&t=1.

11. Hattori Y., Doi K., Sakamoto S., et al. Fingertip replantation. J Hand Surg Am. 2007, 32(4): 548–555.

12. Maroukis BL., Shauver MJ., Nishizuka T., et al. Cross-cultural variation in preference for replantation or revision amputation: Societal and surgeon views. Injury. 2016, 47(4): 818–823.

13. Nishizuka T., Shauver MJ., Zhong L., et al. A comparative study of attitudes regarding digit replantation in the United States and Japan. J Hand Surg Am. 2015, 40(8): 1646–1656.

14. Weichman KE., Wilson SC., Samra F., et al. Treatment and outcomes of fingertip injuries at a large metropolitan public hospital. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013, 131(1): 107–112.

15. Wang K., Sears ED., Shauver MJ., et al. A systematic review of outcomes of revision amputation treatment for fingertip amputations. Hand (N Y). 2013, 8(2): 139–145.

16. Lemmon JA., Janis JE., Rohrich RJ. Soft-tissue injuries of the fingertip: methods of evaluation and treatment. An algorithmic approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008, 122(3): 105e–117e.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2021 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Reconstructive and esthetic breast surgery after solid organ transplantation – a systematic review, proposal of a novel protocol and case presentations

- Characteristics of fingertip injuries and proposal of a treatment algorithm from a hand surgery referral center in Mexico City

- Platelet-rich plasma improves esthetic postoperative outcomes of maxillofacial surgical procedures

- Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma – an evolution through the decades: citation analysis of the top fifty most cited articles

- Bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma

- Three-dimensional navigation in maxillofacial surgery – the way to minimize surgical stress and improve accuracy in fibula free flap and Eagle’s syndrome surgical procedures

- Is it a second scrotum?

- Professor Radana Königová Prize awards

- Editorial

- Fournier’s gangrene secondary to male’s circumcision – a case report and review of the literature

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma

- Platelet-rich plasma improves esthetic postoperative outcomes of maxillofacial surgical procedures

- Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma – an evolution through the decades: citation analysis of the top fifty most cited articles

- Characteristics of fingertip injuries and proposal of a treatment algorithm from a hand surgery referral center in Mexico City

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career