-

Medical journals

- Career

Dysphagia after anterior cervical discectomy and interbody fusion – prospective study with 1-year follow-up

Authors: R. Opsenak; B. Kolarovszki; M. Benco; R. Richterová; P. Snopko; K. Varga; M. Hanko

Authors‘ workplace: University Hospital Martin ; Clinic of Neurosurgery, Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Comenius University in Bratislava

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2019, roč. 98, č. 3, s. 115-120.

Category:

Overview

Introduction:

Dysphagia is a common finding after anterior cervical discectomy. The incidence and severity of swallowing disorders are variable and depend on many factors. Methods: 73 patients after 1 - or 2-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion /ACDF/ were enrolled in prospective, single-center study. The severity of dysphagia was evaluated by the Bazaz-Yoo dysphagia score before surgery and 6 weeks, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery. The impact of factors such as sex, age, number of operated segments, smoking, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, duration of surgery and pre-existing dysphagia on the incidence of dysphagia after surgery was verified. The correlation between the duration of surgery and severity of postoperative dysphagia, and similarly between the age and severity of preoperative and postoperative dysphagia was studied.

Results:

Dysphagia was present in 22% patients within 12 months after surgery. No patient reported severe dysphagia. No significant relationship was demonstrated between sex, age, number of operated segments, pre-existing dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension and the incidence of dysphagia after surgery. Smokers showed a significantly lower incidence of dysphagia before surgery and within 12 months after ACDF (p<0.05). The duration of surgery over 90 minutes significantly increased the incidence of dysphagia within 3 months after ACDF (p<0.05). No significant correlation was confirmed between the duration of surgery, age and severity of postoperative dysphagia.

Conclusion:

Factors such as pre-existing dysphagia, sex, age, number of operated segments, gastroesophageal reflux disease and hypertension have no impact on the incidence of dysphagia after ACDF. Duration of surgery is a risk factor within 3 months after ACDF.

Keywords:

dysphagia – anterior cervical discectomy

Introduction

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is the most common surgical procedure in the treatment of degenerative cervical spine disease. As with other surgical procedures, even with ACDF, intraoperative and postoperative complications can occur. Dysphagia after ACDF is a frequent finding and a well-known complication. Pathophysiology of dysphagia is unclear and the treatment of persistent dysphagia is problematic.

Swallowing is divided into 3 neuroanatomical phases – oral, pharyngeal and esophageal. The oral phase begins with the entry of food into the mouth, which is fragmented by masseter muscle and tongue. The muscles of the tongue, innervated by hypoglossal nerve, handle the bolus of food. The complex coordination of soft palate, tongue movements, salivary glands and masseter muscles, including the information conduction from chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors in the mouth, is ensured with facial, glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves. Pharyngeal phase represents involuntary coordinating of muscle contractions that move food bolus. Critical aspects of this phase are laryngeal elevation and inversion of epiglottis, which prevents the penetration of food into the airways. Superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves provide innervation of pharyngeal phase. Esophageal phase begins with passage of food bolus through the upper esophageal sphincter and ends by passing through the lower esophageal sphincter. This phase is completely involuntary and is performed by coordinated peristalsis of esophageal musculature. Coordination of this phase is provided by autonomous myenteric plexus, which is under control of vagal nerve. Glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves can be damaged during surgical approach involving segment C3 and above, superior laryngeal nerve during an approach involving the intervertebral disc C3-4, and recurrent laryngeal nerve during an approach involving the segment C6 and below. Vagal nerve is naturally protected in the carotid sheath and can be damaged by excessive retraction in the whole subaxial cervical spine.

The impact of various factors on the incidence and severity of postoperative swallowing disorders is still an unanswered question. Many publications examine various risk factors of dysphagia after anterior cervical discectomy. However, results of these studies within the individual risk factors vary and cannot be regarded as uniquely authoritative.

Methods

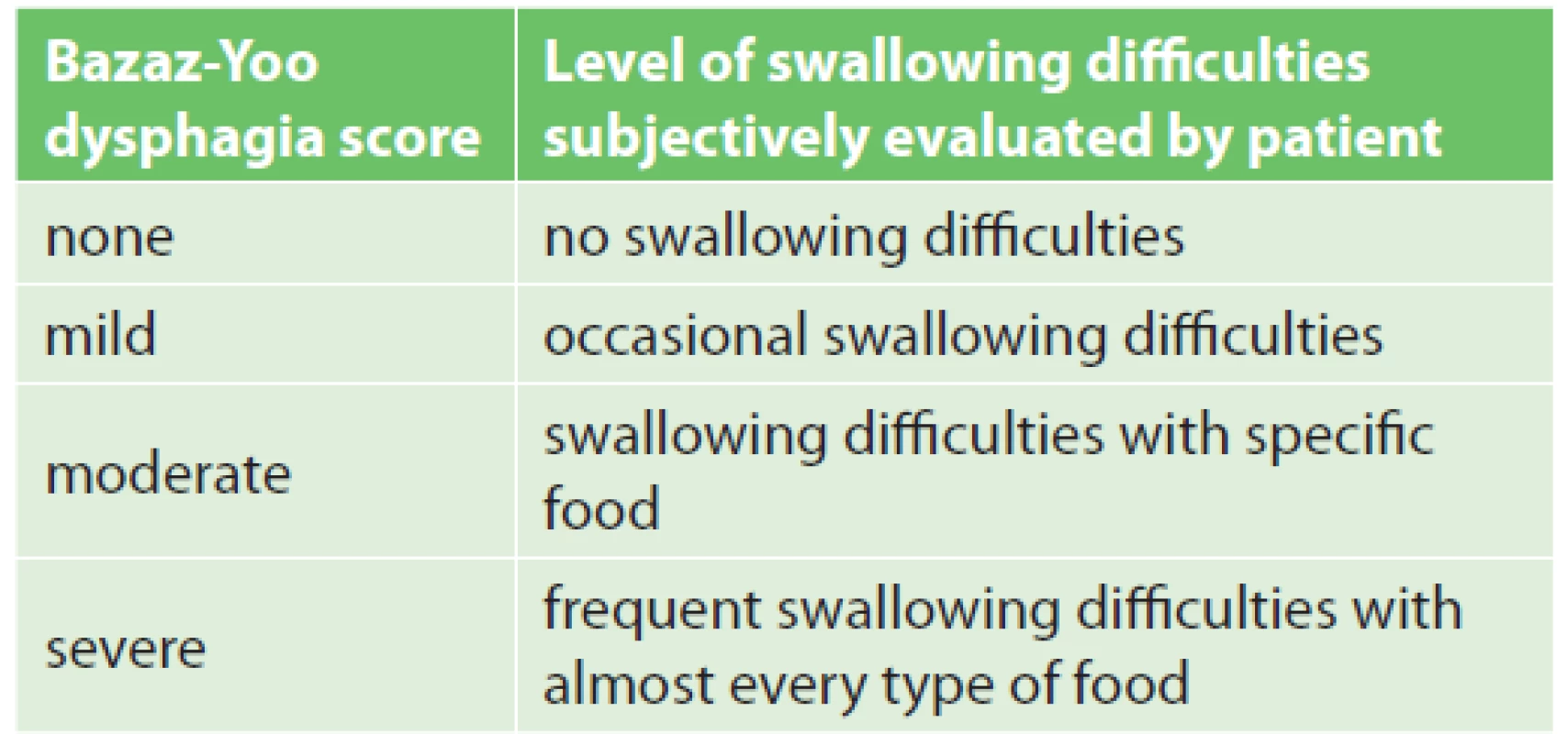

This prospective, single-centre study was done in 73 patients with degenerative cervical spine disease, with the indication and subsequent completion of single - or two-level anterior cervical discectomy using the Smith-Robinson approach. Interbody fusion was induced by implantation of Zero Profile Variable angle® (DePuy Synthes, Switzerland, Fig. 1) and ROI-C® (LDR Medical, France, Fig. 2) cages, filled with osteoconductive synthetic material (Mastergraft® Putty, Sofamor Danek, Medtronic, USA) before implantation. The design of the cages with an integrated plate determines their zero profile and reduces the incidence and severity of postoperative swallowing disorders. The whole patient group, in terms of sex, included 50 women and 23 men. Exclusion criteria included myelopathy, pregnancy, contraindications of elective surgery, severe osteoporosis, cervical spine injury, inflammation and tumor of the cervical spine. All surgical procedures were performed from May 2012 to January 2015. The severity of dysphagia was assessed subjectively by the patients using the Bazaz-Yoo dysphagia score, which is shown in Tab. 1. The severity of swallowing disorders was prospectively recorded before the surgery and within 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after the surgery. After study completion in the studied group, the incidence of dysphagia in the whole group (in above mentioned time periods) was calculated, including its relationship to sex, age, number of operated segments, duration of surgery and risk factors (smoking, gastroesophageal reflux disease, preexisting dysphagia, arterial hypertension). These relationships were assessed using the Fisher’s exact test, by dividing the entire group of patients as follows: men and women, smokers and nonsmokers, patients with/without gastroesophageal reflux disease and patients with/without hypertension. Similarly, we divided the patients into 2 groups according to the presence or absence of swallowing disorders before surgery. According to the duration of surgery, all patients were divided into 2 groups – duration of 90 minutes and less and duration over 90 minutes. The subjects of the study were divided, according to the number of operated segments, into patients after 1 - and 2-level cervical discectomy. According to age, we divided the patients into 2 groups – age up to 55 years and age of 55 years or more. The statistically significance level was defined as p <0.05.

1. X-ray image after implantation of Zero Profi le VA cage in levels C5-6, C6-7

(Authors´ archive) 2. X-ray image after implantation of ROI-C cage in level C5-6

(Authors´ archive) 1. Bazaz-Yoo dysphagia score (adapted from Bazaz et al., 2002)

In particular, we evaluated the correlation between the severity of dysphagia and patient age before the surgery and 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after the surgery (using the Spearman correlation coefficient). For the interpretation of the Spearman correlation coefficient a Cohen scheme was used – where absolute values up to 0.1 mean a trivial correlation, values between 0.1 to 0.3 mean a weak correlation, values between 0.3 to 0.5 mean a moderate correlation and values above 0.5 mean a strong correlation [1]. For the correlation of dysphagia severity and patient age we used the Kruskal-Wallis test, while a statistically significant correlation was defined by p <0.05. We also evaluated the correlation between the severity of dysphagia and the duration of surgery, in time periods of 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after surgery. Correlation between the severity of dysphagia and the duration of surgery was evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test. A significant effect of factors such as pre-existing dysphagia, the number of surgical segments, the duration of surgery, and esophageal reflux disease on the incidence of dysphagia after ACDF was predicted. Strong correlation between the duration of surgery and severity of dysphagia after surgery was predicted. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jessenius Faculty of Medicine in Martin, Comenius University in Bratislava – protocol number EK 1491/2014.

Results

Anterior cervical discectomy in segments C3-4, C4-5, C5-6 and C6-7 was performed in the enrolled patients. Level C5-6 was the most commonly treated motion segment (77%), followed by segment C6-7 (56%).

No patient reported severe dysphagia according to the Bazaz-Yoo dysphagia score throughout the follow-up period. In the whole group, preoperative dysphagia was present in 14% patients; of these, mild dysphagia occurred in 8% cases and moderate dysphagia in 6% cases. Six weeks after the surgery, 53% patients reported swallowing disorders; of these, 45% patients reported mild dysphagia and 8% moderate dysphagia. Three months after the surgery, the incidence of dysphagia in the whole group was 33%, reaching a mild degree in 29 % and a moderate degree in 4%. Six months after the surgery, 19% patients reported swallowing disorders – a mild degree in 18 % and a moderate degree in 1%. Twelve months after the surgery, 22% patients reported dysphagia – mild in 19% and moderate in 3%.

The studied group included 68% women and 32% men. No significant relationship between the incidence of dysphagia and sex was demonstrated during the observation period.

As regards the age, the studied group included 56% patients under the age of 55 years and 44% in the age 55 years or more. No significant relationship between the incidence of preoperative and postoperative dysphagia and patient age was demonstrated throughout the observation period. The correlation between patient age and severity of preoperative and postoperative dysphagia was weak, even trivial. No correlation between the age of patients and severity of swallowing disorders was detected throughout the observation period.

1-level ACDF was performed in 45% patients of the whole group; 2-level ACDF was carried out in 55%. No significant relationship between the number of operated segments and the incidence of dysphagia was detected throughout the postoperative period.

The studied group included 42% smokers. Preexisting dysphagia was reported by 3% smokers and by 21% non-smokers; this difference was statistically significant (p=0.037). This difference could be considered as a characteristic aspect of our studied group. No significant relationship between smoking and the incidence of dysphagia was demonstrated in the period of 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months after the surgery. Smokers had a significantly lower incidence of swallowing disorders in the period of 12 months after the surgery compared to non-smokers (p=0.044).

Gastroesophageal reflux disease occurred in 14% patients in our group. No significant relationship between the incidence of dysphagia and the occurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease was demonstrated throughout the observation period.

Arterial hypertension was present in 45% patients in the group, while no significant relationship was found between the incidence of dysphagia and arterial hypertension throughout the observation period.

Similarly, no significant relationship between the incidence of preoperative and postoperative dysphagia was confirmed throughout the observation period.

Mean duration of the surgery in the whole group of patients was 100 minutes, while the mean duration of 1-level ACDF was 78 minutes and that of 2-level ACDF was 116 minutes. Three months after ACDF lasting more than 90 minutes, there was a significantly higher incidence of dysphagia compared to surgeries with a duration of 90 minutes and less (p=0.027). No significant relationship between the duration of surgery and the incidence of dysphagia was demonstrated at the other time points of the observation period. The correlation between the duration of surgery and severity of postoperative dysphagia was trivial at the time points of 6 weeks and 3 months and was not present at 6 and 12 months. Similarly, the Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed no such correlation in the postoperative period.

Discussion

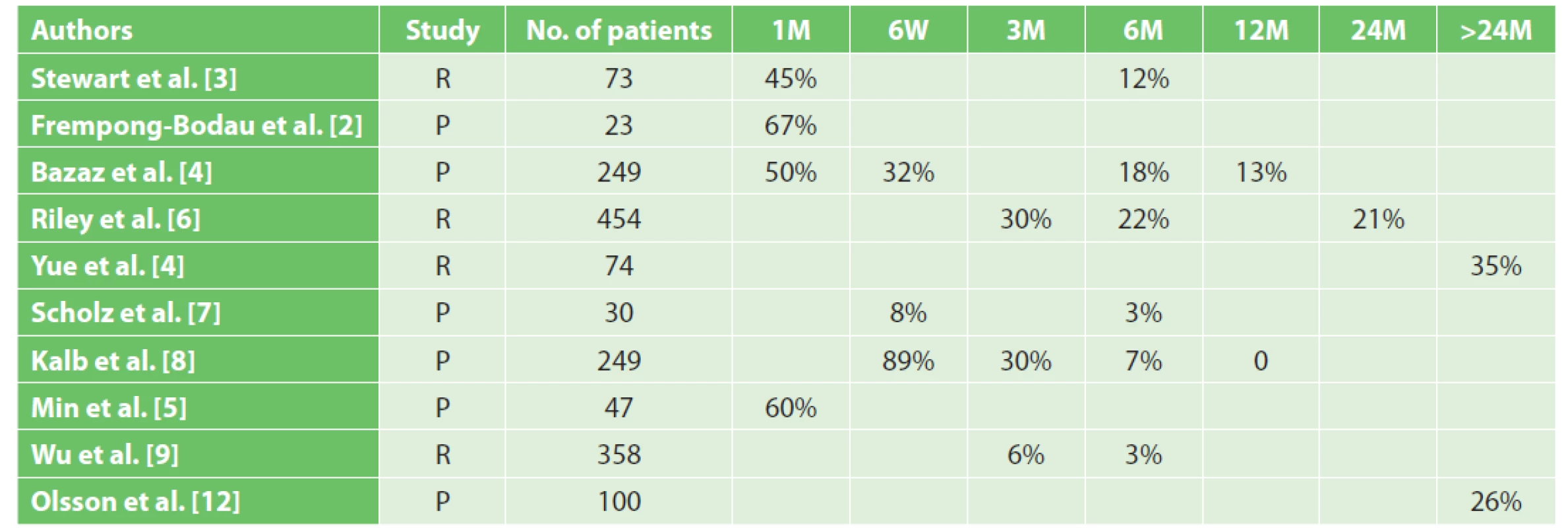

Published incidence of dysphagia after ACDF varies in a wide range 0−89%, and decreases with time from the surgery (Tab. 2). These studies have confirmed the presence of dysphagia after anterior cervical approaches in the early post-operative period, of around 50 % [2−5]. In the majority of patients, regression of swallowing disorders (3–12%) has occurred within 6 months after surgery, while 12 months after surgery the incidence of dysphagia was only around 13 % [3−9]. In our study, the incidence of dysphagia 6 weeks after ACDF was 53 % of all cases and decreased to 19 % in time period 6 months after surgery. These results are comparable with the findings of other published studies. The incidence of dysphagia in our studied group, 12 months after the surgery, was higher (22%) than in most of the published studies. As reported by Reinard et al. based on a retrospective analysis of patients after combined cervical approaches (anterior and posterior), the overall incidence of dysphagia was 37.7% [10].

2. Clinical studies evaluating the incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical discectomy

Note: R – retrospective study, P – prospective study, M – month, W – week) As confirmed by some studies, dysphagia persisted for more than 1 year in a majority of patients after ACDF. Yue et al. followed 74 patients for the mean duration of 7 years after anterior cervical approaches and verified an overall incidence of dysphagia at the level of 35% [11]. Olsson et al. reported the incidence of persisting dysphagia, during 33 months on average, after anterior cervical approaches at the level of 26% [12]. Smith-Hammond et al., in their prospective study with a 3-year follow-up period, followed the incidence of dysphagia after anterior and posterior cervical approaches and found that 20% of patients after posterior approaches had swallowing disorders, while endotracheal intubation was absent as a risk factor in this study [13].

Some studies referred the presence of dysphagia just before ACDF. In our study, the incidence of dysphagia before surgery was at 14%, while preexisting dysphagia was present significantly more often in the group of non-smokers compared to smokers.

Frempong-Bodau et al. found swallowing abnormalities before surgery in 66% of patients with myelopathy, which was verified by the passage of barium. As assumed by these authors, the cause of dysphagia in these patients was the failure of local reflex mechanisms on a preganglionic sympathetic level due to spinal cord compression. Significantly persisting dysphagia occurred in this group of patients after surgery [2]. In our study, the finding of myelopathy based on imaging assessments was used as an exclusion criterion.

The severity of dysphagia after surgery in our study was evaluated by the patients themselves using the Bazaz-Yoo dysphagia score (Tab. 1). This scoring system was used for the first time by Bazaz et al. who prospectively analyzed 249 patients after anterior cervical discectomy or corpectomy. One month after surgery, they referred 5.6% of cases of severe dysphagia. Olsson et al. reported a similar incidence of severe dysphagia [4,12]. In our study, throughout the whole observation period, no severe dysphagia occurred, according to the Bazaz-Yoo dysphagia score. Predominantly, mild dysphagia occurred in the group of patients.

For the formation of interbody fusion after ACDF, hollow cages with an integrated plate were used in our study. The integrated plate in the body of the cage determines its zero profile (Zero Profile VA, DePuy Synthes, Switzerland, Fig. 1; ROI-C, LDR Medical, France, Fig. 2). In contrast with the usage of a conventional anterior cervical plate, there is no irritation of the hypopharynx and esophagus. Lee et al. examined the importance of the anterior cervical plate design as a risk factor for the development of swallowing disorders after ACDF. In their prospective study, the authors found that the use of the cervical plate Zephir (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, USA) was associated with a lower incidence of postoperative dysphagia compared to the plate Atlantis from the same manufacturer. The authors explained this finding by a smoother surface and a lower profile of the cervical plate Zephir [14]. This study predicted a lower incidence of dysphagia after surgery by using implants with a zero profile. In their meta-analysis, Yang Y et al. reported the incidence of dysphagia after ACDF using a zero-profile implant at 15.6% [15]. In their retrospective study, Yang H et al. reported reduced dysphagia after implantation of the cage with an integrated plate and a zero profile, compared to implantation of a cage with the conventional anterior cervical plate [16]. Segebard et al. reported the incidence of dysphagia after cervical arthroplasty at 15.8%, compared to the interbody fusion with plate (42.1%). This finding also explains the zero profile of an artificial disc, compared to the design of the conventional cervical plate [17]. Based on their retrospective analysis of 44 patients with persistent swallowing disorders after ACDF, Fogel et al. reported a regression of dysphagia after removing the conventional anterior cervical plate and performing adhesiolysis during surgical revision in 55 % cases. Intraoperatively, they observed extensive adhesions between the esophagus and the plate. [18]. The use of cages with an integrated plate thus presupposes the elimination of extensive fibroadhesive changes.

The factors that are usually associated with an increased risk of postoperative dysphagia include: the number of operated segments, female sex, long operating time and the age over 60 years [19]. In our study, no significant relationship between the number of operated segments, sex, age and the incidence of dysphagia after surgery was confirmed. These findings were confirmed by the Olsson’s cohort study [12]. The duration of surgery had a significant influence on the incidence of dysphagia at 3 months after the surgery. No significant correlation between patient age, duration of the surgery and severity of postoperative dysphagia was demonstrated. Esophageal reflux disease, preexisting dysphagia and arterial hypertension had no significant effect on the incidence of postoperative swallowing disorders. Smokers in our group had a significantly lower incidence of dysphagia 12 months after the surgery, compared to non-smokers. Smoking thus does not represent a risk factor for the incidence of postoperative dysphagia, which was also confirmed by the Olsson’s cohort study in 2015 [12].

Factors without any recorded correlation with postoperative dysphagia include: headache, type of incision (transverse, arched, longitudinal), the size of anterior osteophytes, pseudoarthrosis, subsidence of the implant, dislocation or breaking of the implant, intubation, severity of myelopathy, retraction of the esophagus, osteoarthritis, alcohol abuse and obesity [19].

Preventive measures reducing the incidence of postoperative dysphagia after ACDF include: gentle surgical technique, proper haemostasis during the surgery and application of a drain at the end of the surgery in order to prevent any haematoma. In their prospective study, Pedram et al. excluded any preventive effect of the application of corticosteroids on the incidence of postoperative dysphagia [20]. Maintaining a low pressure in the endotracheal tube, as well as desufflation and insufflation of the endotracheal tube cuff during the surgery, reduces the incidence of postoperative dysphagia [21,22].

Conclusion

The incidence of dysphagia in the early postoperative period after ACDF is around 50%, while in the subsequent period (3−12 months after the surgery) the incidence of swallowing disorders decreases. In the postoperative period, most of the patients report a mild degree of dysphagia. Severe dysphagia after ACDF does not occur. Factors such as the sex, age, gastroesophageal reflux disease and arterial hypertension have no impact on the incidence of preoperative and postoperative dysphagia. The number of operated levels and preexisting dysphagia have no significant impact on the incidence of postoperative dysphagia. Smoking is a preventive factor in the preoperative period and 12 months after ACDF. The duration of the surgery is a risk factor in the period of 3 months after the surgery. The duration of surgery and patient age show no significant correlation with the severity of postoperative dysphagia throughout the observation period. The predicted significant impact of factors such as pre-existing dysphagia, the number of operated segments, and gastroesophageal reflux disease was not confirmed in this study. The assumed strong correlation between the duration of surgery and severity of dysphagia after the surgery was not confirmed, either. The only significant risk factor for the incidence of dysphagia after ACDF was the duration of the surgical procedure. To obtain more representative results, a longer follow-up of a larger group of patients is necessary, with a focus on a wider range of potential risk factors.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with this paper and that the article has not been published in any other journal.

Rene Opsenak MD., Ph.D.

Kollarova 2

036 59 Martin

e-mail: opsenak@gmail.com

Sources

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrance Earlbaum Associates 1989 : 567.

- Frempong-Bodau A, Houten JK, Osborn B, et al. Swallowing and speech dysfunction in patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a prospective, objective preoperative and postoperative assessment. J Spinal Disord Tech 2002;15 : 362−8.

- Stewart M, Johnston RA, Stewart I, et al. Swallowing performance following anterior cervical spine surgery. In Br J Neurosurg 1995;9 : 605−9.

- Bazaz R, Lee MJ, Yoo JU. Incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study. Spine 2002;27 : 2453−8.

- Min Y, Kim WS, Kanq SS, et al. Incidence of dysphagia and serial videofluoroscopic swallow study findings after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: a prospective study. Clin Spine Surg 2016;29 : 177−81. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000060.

- Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL, Albert TJ, et al. Dysphagia after anterior cervical decompression and fusion: prevalence and risk factors from a longitudinal cohort study. Spine 2005;30 : 2564−9.

- Scholz M, Schnake KJ, Pingel A, et al. A new zero-profile implant for stand-alone anterior cervical interbody fusion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469 : 666−73.

- Kalb S, Reis MT, Cowperthwaite MC, et al. Dysphagia after cervical spine surgery: incidence and risk factors. In World Neurosurg 2012;77 : 183−7.

- Wu B, Song F, Zhu S. Reasons of dysphagia after operation of anterior cervical decompression and fusion. Clin Spine Surg 2017;30 : 554−59. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000180.

- Reinard KA, Cook DM, Zakaria HM, et al. A cohort study of the morbidity of combined anterior-posterior cervical spinal fusions: incidence and predictors of postoperative dysphagia. Eurospin J 2016;25 : 2068−77. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4429-0.

- Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Persistent swallowing and voice problems after anterior cervical discectomy anf fusion with allograft and plating: a 5 - to 11-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J 2005;14 : 677−82.

- Olsson EC, Jobson M, Lim MR. Risk factors for persistent dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery. Orthopedics 2015;38 : 319−23.

- Smith-Hammond CA, New KC, Pietrobon R, et al. Prospective analysis of incidence and risk factors of dysphagia in spine surgery patients: comparison of anterior cervical, posterior cervical, and lumbar procedures. Spine 2004;29 : 1441−6.

- Lee M, Bazaz R, Furey C, et al. The incidence of dysphagia in anterior cervical surgery as a function of plate design: a prospective study. In CSRS 32nd annual meeting. Boston, MA 2004.

- Yang Y, Ma L, Liu H, et al. A meta-analysis of the incidence of patient-reported dysphagia after anterior cervical decompression and fusion with the zero-profile implant system Dysphagia 2016; 31 : 134−45. doi: 10.1007/s00455-015-9681-7.

- Yang H, Chen D, Wang X, et al. Zero-profile integrated plate and spacer device reduces rate of adjacent-level ossification development and dysphagia compared to ACDF with plating and cage system. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015;135 : 781−7.

- Segebarth B, Datta JC, Darden B, et al. Incidence of dysphagia comparing cervical arthroplasty and ACDF. SAS Journal 20104 : 3−8.

- Fogel GR, McDonnell MF. Surgical treatment of dysphagia after anterior cervical interbody fusion. Spine J 2005;5 : 140−4.

- Anderson KK, Arnold PM. Oropharyngeal dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a review. Global Spine J 2013;3 : 273−86.

- Pedram M, Castagnera L, Carat X, et al. Pharyngolaryngeal lesions in patients undergoing cervical spine surgery through the anterior approach: contribution of methylprednisolone. Spine J 2003;12 : 84−90.

- Apfelbaum RI, Kriskovich MD, Haller JR. On the incidence, cause, and prevention of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsies during anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine 2000;25 : 2906−12.

- Ratnaraj J, Todorov A, McHugh T, et al. Effects of decreasing endotracheal tube cuff pressures during neck retraction for anterior cervical spine surgery. J Neurosurg 2002;97(2 Suppl.): 176−9.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2019 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Všeobecná chirurgie?

- Current view on prostheses in herniology (hernia meshes) – classifications, indications, advantages and disadvantages of different implants, complications J. Skach, M. Slamborova, V. Blecher, P. Hromadka, R. Gurlich

- Animal models of liver diseases and their application in experimental surgery

- Assessment of anastomosis perfusion by fluorescent angiography in robotic low rectal resection: the results of a non-randomized study

- Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome in a patient with cystic fibrosis after lung transplantation

- Zemřel primář Michal Leško

- Pracovní dny Koloproktologické sekce České chirurgické společnosti ČLS JEP

- Dysphagia after anterior cervical discectomy and interbody fusion – prospective study with 1-year follow-up

- Primary retroperitoneal Ewing’s sarcoma

- Hip synovial cyst presenting as femoral hernia – case report

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Current view on prostheses in herniology (hernia meshes) – classifications, indications, advantages and disadvantages of different implants, complications J. Skach, M. Slamborova, V. Blecher, P. Hromadka, R. Gurlich

- Hip synovial cyst presenting as femoral hernia – case report

- Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome in a patient with cystic fibrosis after lung transplantation

- Zemřel primář Michal Leško

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career