-

Medical journals

- Career

Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit

Authors: A. Furdová 1; M. Michalková 2; L. Javorská 2

Authors‘ workplace: Klinika oftalmológie Lekárskej fakulty Univerzity Komenského a Univerzitná nemocnica, Nemocnica Ružinov, Bratislava prednosta: doc. MUDr. Krásnik Vladimír, PhD. 1; Oftalmologické oddelenie JZS, Nemocnica Poprad a. s. prednostka: MUDr. Michalková Mária 2

Published in: Čes. a slov. Oftal., 74, 2018, No. 1, p. 37-43

Category: Original Article

Overview

The incidence of Merkel cell carcinoma has tended to increase worldwide in recent years. Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare tumor of the skin that occurs mainly in the sun exposed sites. The malignant reversal of Merkel cells is currently associated with an infection caused by a Merkel cell polyomavirals. In some cases, the disease may have a relatively inconspicuous clinical picture in the initial phase, which is in contrast to its extensive microscopic propagation. For this reason, the risk of late diagnosis or insufficient primary surgery is increased. The diagnostic standard is histological and, in particular, immunohistochemical examination of tumor tissue samples. Merkel cell carcinoma is a marked tendency to local recurrence and early development of metastases in regional lymph nodes, followed by generalization. The basis of treatment is radical excision of the tumor by in most cases by adjuvant radiotherapy targeted at primary place of occurrence and the area of regional draining lymph nodes. The effectiveness of different chemotherapeutic protocols in Merkel cell carcinoma is mostly low and the median survival is low. From a prognostic point of view, Merkel cell carcinoma plays the most important role of staging the tumor at the time of capture. The suspected lesions in the area around the eye, eyelid and orbit need to indicate adequate therapeutic approach that the detection of the disease at the earliest stage. The authors describe the clinical experience in 2 patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit.

Key words:

eyelid tumors, tumors of the orbit, Merkel cell carcinoma

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a relatively rare, primary malignant tumour of the skin. Clinically it is usually manifested as nodular, sometimes on the surface as an exulcerated affliction of reddish-purple colour, which affects areas of the skin exposed to solar radiation, most frequently the face and limbs [1, 2]. Merkel cell carcinoma is a highly aggressive neuroendocrine skin tumour, first described by Toker [3] in 1972 as “trabecular cell carcinoma”. The tumour primarily originates from the Merkel cells localised in the basal layer of the epidermis. These cells develop from epidermal skin cells and have their origin in embryonic skin. In adult mice epidermal skin cells progressively replace the decaying population of Merkel cells. The transcription factor atonal homolog 1 (Atoh1) is essential for stem cells to become Merkel cells [4]. At present, research is being conducted to investigate the possibilities of regulating this factor in relation to the differentiation of Merkel cells and the development of MCC.

The tumour is formed by smaller, phenotype-primitive, relatively uniform cells, which have relatively poor cytoplasm. The nuclei of the tumour cells are rounded, folliculose, with a fine chromatin sketch and numerous nucleoli. High mitotic activity of the tumour cells is symptomatic, and there may also be atypical mitoses. The tumour usually forms larger, solid deposits, manifesting a characteristic infiltrative growth of diffuse type, less frequently it is manifested in trabecular formations [5].

The tumour occurs primarily in areas exposed to sunlight in the Caucasian race, particularly in men. Exceptional cases have been recorded also in childhood age [6]. The incidence of MCC has manifested an increasing tendency in recent years. According to the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) register in the United States, in 1986 the annual incidence was 1.5 cases per one million of the population, rising to 4.4 cases per million in 2001 [7]. The American Cancer Society envisages as many as 1 500 new cases of MCC in the USA [8], therefore almost five cases per million of the population. Similar data has been presented also for the European and Australian population [9, 10].

In comparison with melanoma, MCC is characterised by double the rate of fatality and an increasing incidence [7]. After surgical removal, the tumour has a tendency toward local recurrence (27-60%), early affliction of the regional nodes (45-91%) and remote metastases (18-52%) [11]. Malignant reversal of Merkel cells is caused by a sequence of the discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) into the cell genome [12].

The tumour most frequently occurs on the head and neck (40-75%), whereas by contrast only 10-27% of tumours develop on the areas of the torso and buttocks [13]. As a rule, it is manifested clinically as a painless, resistant, semi-spherical, red to livid coloured bulging tumour of a size within the range of 0.3-15 cm [14]. Macroscopically it mostly appears to be well-bordered and homogeneous, which is in contrast with its extensive microscopic propagation. Upon growth on the torso and area of the buttocks, the tumour may appear as a deeply embedded nodule of coloured skin in the subcutaneous layer, reminiscent of a cyst [15]. This seemingly benign appearance increases the risk of late diagnosis, as well as of insufficient primary excision of the tumour.

Its appurtenance to the neuroendocrine system is documented by an electron microscope image of electron-dense neurosecretory granules in tumour cells and in certain cases it is possible to detect also the presence of intranuclear and cytoplasmatic inclusions of the MCPyV.

Upon a basic histological examination it is necessary to use differential diagnostics to differentiate metastatic small-cell carcinoma of the lungs, neuroblastoma, skin lymphoma, metastatic carcinoids, amelanotic melanoma, carcinoma of the sweat glands, Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Ewing's sarcoma [16]. It is therefore necessary to conduct a thorough full clinical examination and mainly an immunohistochemical examination of the tumour tissue. There is a possibility of affiliated incidence together with other tumours, for example with cancer of the breasts or ovaries, leukaemia, malignant lymphoma and anaplastic meningioma [17]. Other skin neoplasias occur in the anamnesis of 20-50% of patients with MCC, in particular basal cell carcinoma.

In determining the stage of the tumour, a significant role is played by positron emission tomography/computer tomography (PET / CT). It is capable of detecting with a high degree of sensitivity both affliction of the regional lymph nodes and any recurrence or presence of remote metastases. It is also suitable for the planning and evaluation of the effectiveness of targeted radiotherapy and the effect of applied chemotherapy [18].

MCC is typified by a tendency toward frequent local recurrence and early development of metastases into regional nodes, with subsequent generalisation of the pathology. This aggressive growth potential means that without therapy the tumour may double its size within the course of one week [8], which has led to the study of the pro-growth characteristics of MCC cells. The first mention of genetic alteration of growth factor receptors in MCC was published by Swick et al. [19].

Malfunction of regulation of the cell cycle appears to be fundamental for the formation of a tumour. MCC has a markedly higher incidence in patients following immunosuppressive transplants and patients with AIDS in comparison with the ordinary population, which is similar to the case of incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma. Its similarity with this tumour, in the etiopathogenesis of which a role is played by the herpes virus associated with Kaposi's sarcoma, led to the hypothesis that MCC may also be upon a background of viral infection. The presence of MCPyV in MCC has been confirmed by several independent groups [20–22]. The frequency of virus-positive cases is generally high (within the range of 69-85%), with the exception of the Australian population, where the presence of the virus has been identified in only 24% of MCC. MCPyV subsequently expresses small and large T antigen, which are multifunctional proteins. From a prognostic perspective, the significance of the presence of MCPyV infection in MCC is unclear, and opinions differ. Tumours in which tissue presence of MCPyV has been identified have a worse prognosis. Patients whose MCC genome contains viral DNA usually have a more promising course of the pathology [23].

In addition to viral etiology, other factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of the tumour. The origin of MCC may be contributed to also by ultraviolet radiation (UV), and the risk increases with increased exposure to UV B radiation [24, 25]. The role of UV radiation in this respect is rather immunosuppressive than mutagenic, in which induction of the immunosuppressive cytokines IL 10 and TNF and isomerisation of trans urocanic acid into cis urocanic acid and the formation of reactive acidic radicals is considered to be decisive [26, 27]. This observation is in accordance with the evident epidemiological link between the use of immunosuppressant drugs and MCC [28]. For example, in patients following a kidney transplant the incidence of MCC is as much as 15 times higher in comparison with the regular population. In a Finnish study, drawing data from the National Renal Transplant Register and the Finnish Cancer Registry, out of 4 200 patients following a kidney transplant the authors determined three cases with MCC [29]. Similar observations of more frequent incidence of MCC in immunocompromised patients and at a significantly lower age in comparison with age-comparable control groups have been made also by other authors [30–32]. On the other hand, a range of case reports have been published with spontaneous regression of MCC, which was observed also following an improvement of immune functions after a reduction of immunosuppressive therapy. For example, Friendlander et al. documented a terminally ill patient following a kidney transplant, in whom a temporary regression of MCC took place after the elimination of cyclosporine from the immunosuppressive protocol [33]. After verification of MCC on a background of a biopsy or excision of a suspected skin lesion, further therapy should be conducted by a surgical centre specialised in the treatment of malignant melanoma. The basis of this therapy is radical excision, or in the case of positive resection boundaries, re-excision of the tumour, always supplemented by a biopsy of the sentinel node. The surgical procedure should be followed up by adjuvant radiotherapy, targeted at the place of primary occurrence, and at the area of the regional draining lymph nodes, in the case that the primary tumour is larger than 2 cm, upon positive resection boundaries or close to the tumour to these boundaries and upon angiolymphatic invasion [34]. Radiotherapy is also unequivocally recommended upon a positive biopsy of the sentinel node, or if the nodes have not been histologically examined [35], as well as in immunocompromised patients.

No randomised trials exist evaluating the effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with MCC. Similarly, there is only a small amount of data about the effectiveness of different chemotherapeutic protocols, and the presented conclusions are contradictory [36, 37]. The largest amount of experience has been acquired with protocols used in the first line of treatment of small-cell carcinoma of the lungs, containing etoposide and carboplatin [38]. The effect of this treatment is described in 60-75% of cases, although with a few exceptions the median survival is low [39, 40].

The result of treatment is dependent upon the development of new therapeutic procedures. Within this context, a range of antibodies has been tested against surface receptors belonging to the protein kinase signalling network, trastuzumab against ErbB 2 receptor (Her 2 / Neu oncogene) and cetuximab against EGF (epidermal growth factor) receptor. However, these receptors are not generally exprimated in MCC [41]. In the case of expression of c kit (CD117), VEGF receptors and PDGF receptors, the possibility of influencing the tumour prolifeation is offered through the application of sorafenib or sunitinib [42], and for tumours exprimating PDGF receptors also through the administration of imatinib mesylate [19]. Increased expression of the antiapoptotic protein MC 1, a member of the family of Bcl 2 proteins, and Bmi 1, a transcription repressor belonging to the family of the polycomb group of proteins influencing the regulation of the cell cycle, proliferation and cell regeneration [42], has also been observed in the case of MCC. The inhibition of these expression genes responsible for cell proliferation and apoptosis with the aid of antisense oligonucleotides or microRNAs could also be a promising path for how to influence tumour growth [43]. Further studies shall be necessary for clarification of the significance of this anti-tumour and anti-angiogenic treatment. Also remaining to be verified is the anti-neoplastic effect of IFN alpha, which in vitro reduced the proliferation of cell lines, DNA synthesis and induced apoptosis of MCC cells [44]. It shall also be necessary to verify further potential therapeutic approaches, with clarification of the role of role Atoh1 transcription factor in the differentiation of Merkel cells, regarding whether Atoh1 functions on Merkel cells as a tumour suppressant gene, and also what the possibilities are for its regulation with the use of anti-tumour therapy [45].

From a prognostic perspective, the most significant role in MCC is played by the staging of the tumour at the time of identification of the pathology. A localised tumour smaller than 2 cm without metastases into the lymph nodes has a good prognosis. Tumours with a size of more than 2 cm are linked with a high risk of generalisation [46]. Further factors are so far in the stage of research, with regard to their potential influence on patients' prognosis.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

Case reports of two patients with MCC. In the first case the patient was repeatedly surgically treated for a chalazion, without indication for histological examination. In the second case the patient was repeatedly treated by incision of an abscess of the upper eyelid and the area of the supercilium, without indication for histological examination. Both cases were initially viewed as a potentially fatal pathology – MCC.

RESULTS

Case report 1

The patient, a 75 year old woman, was treated from 2008 for essential thrombocythaemia – Ticlopidine, in 2010 she underwent hysterectomy and adnexectomy for papillary cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary, in April 2013 B-chronic lymphatic leukaemia was detected. She is being treated further for a chronic ulcerous pathology and rheumatoid arthritis.

The patient was referred to an ophthalmologist in May 2012 due to a small vascularised tumour persisting for two months on the edge of the upper eyelid, passing onto the intermarginal strip, internal margin preserved. Electro-cauterisation of the tumour was performed in outpatient care. Six months later the patient again reported complaints and was indicated for excochleation of the chalasia of the upper eyelid of the left eye. The finding did not improve, as a result of which 3 months later Diprophos was applied by injection into the lesion. Subjectively the finding worsened, the eyelid swollen. The patient was observed by a district ophthalmologist. In March 2013 she was again sent to hospital due to a persisting 2 cm large granulomatous tumour of the eyelid, edges rolled, tumour vascularised, infiltrating via the intermarginal strip onto the tarsal conjunctiva. Extirpation under microscope was indicated, material was sent for histological examination. Conclusion of histopathological examination: incompletely extirpated lesion of Merkel cell carcinoma. Subsequent general chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Sent for treatment to Košice, in June 2013 complete extirpation of tumour of left upper eyelid, defect replaced by cartilage from nose at the Plastic Surgery Clinic in Košice, with histological confirmation of MCC carcinoma.

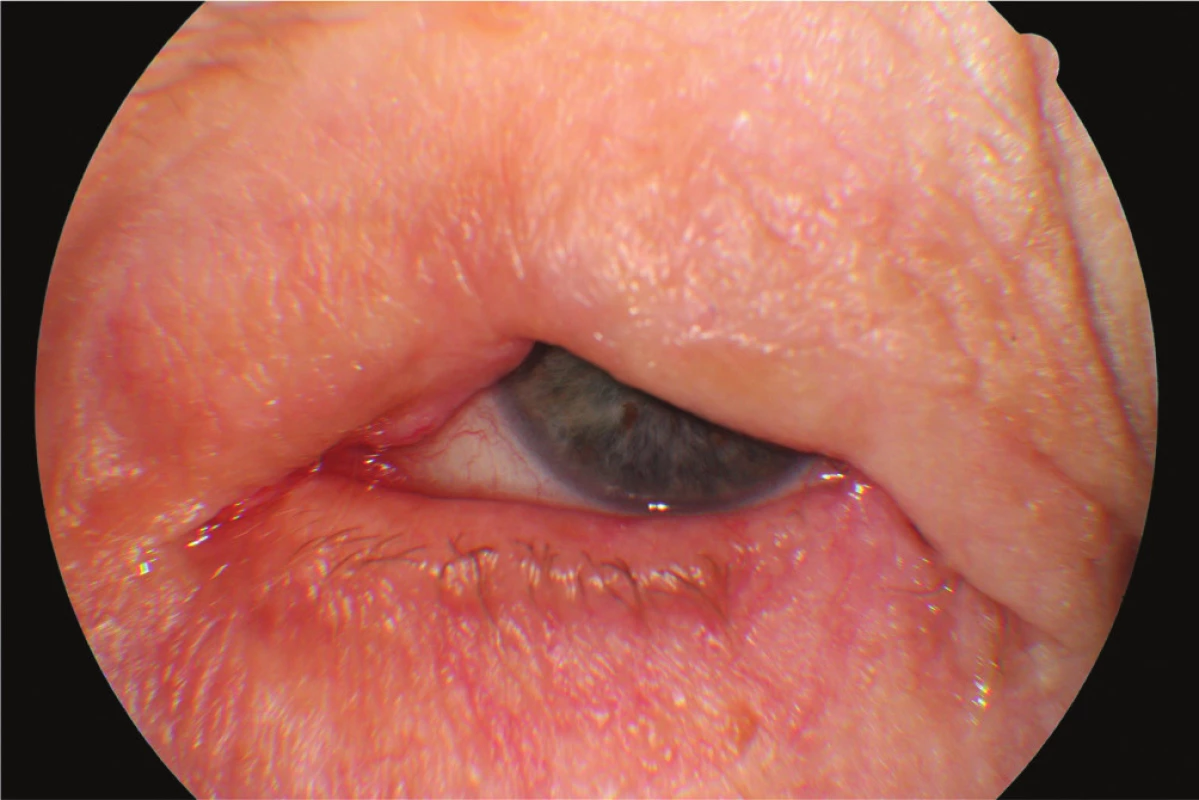

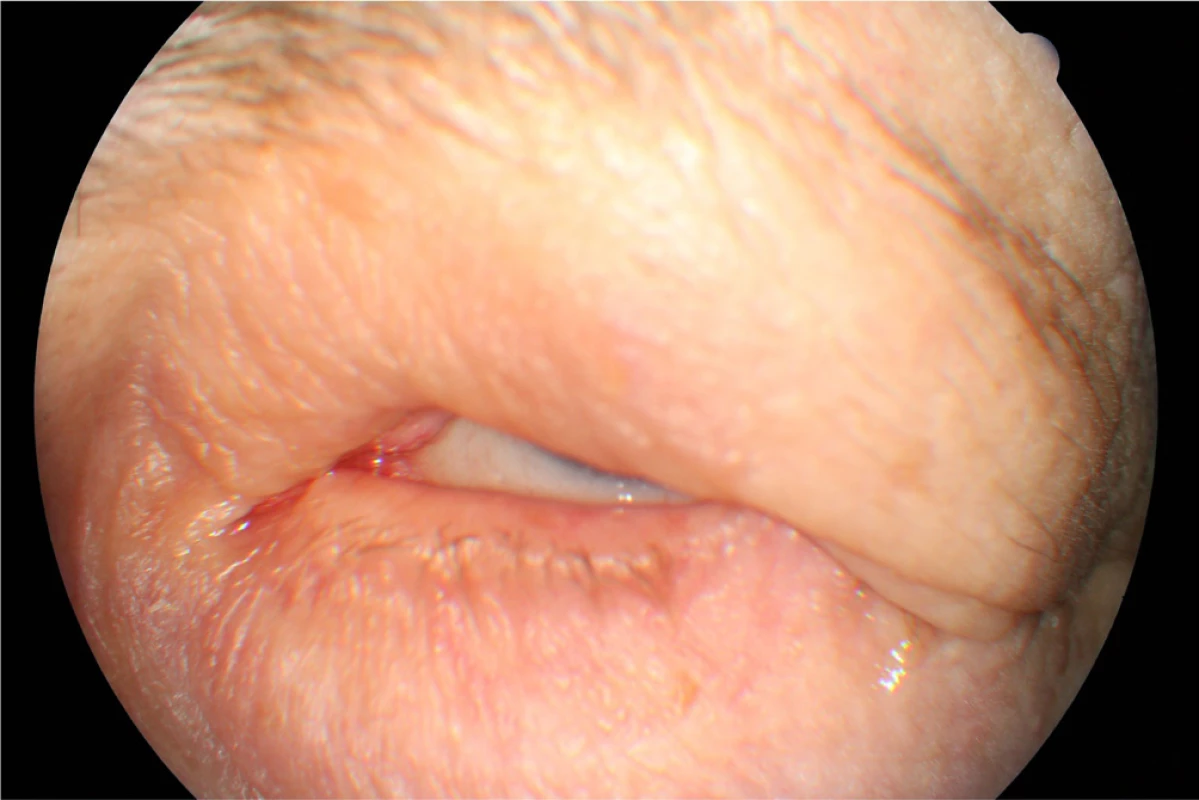

In April 2014 the patient underwent cataract surgery (FAKO + IOL o.sin), but lagophthalmos persisted due to paresis of n. facialis following extirpation of preauricular metastases (MTS). Lateral tarsorrhaphy performed, epilation of trichiasis subsequently repeatedly performed (fig. 1, 2).

1. Clinical findings Patient 1 in year 2015

2. Clinical findings Patient 1 in year 2015 by the maximum effort to close the eyelids

In February 2015 the patient was indicated for CT examination of the neck region – nodular mass detected in hypodermis on the level of the mandible on the left side as a further, new finding. Even despite general therapy – general CHT continuing at last dose of second line CHT – recurrence, further RT indicated on neck region. In June 2015 the patient was indicated for tracheostomy due to post-radiation edema of the face and throat, open wounds persisting following block dissection and extirpation of MTS on neck and shoulders. The patient died of general dissemination of the pathology.

Case report 2

The patient, a 68 year old woman, in January 2017 began to suffer swelling of the left upper eyelid up to the eyebrow. She was treated by a district surgeon with repeated incisions for approximately 3 months. The patient reported without documentation. The size of the swelling increased, as a result in March 2017 the patient was sent to an ophthalmologist due to “problems with vision” and constriction of the visual field. Examination at our outpatient department confirmed edema of the eyelids, with presence of mucous purulent secretion from the conjunctival sac, as well as a solid lesion in the region of the upper eyelid and supercilium. Central visual acuity 1.0 without correction l.utq. We indicated surgical solution of the tumorous mass in the region of the eyelid and supercilium and sent the material from the excision for histological examination. After surgery healing p.p.i. (fig. 3, 4). The histopathological examination confirmed Merkel cell carcinoma, edges were not loose.

3. Clinical findings Patient 2 after repeated excisions in upper eyelid and supercilium due to “oedema”

4. Patient 2 – detail of lesion in part of upper eyelid and supercilium in April 2017

In April 2017 the patient was sent for CT examination of the orbit, a hyperdense polyglobular lesion was confirmed, infiltrating into the soft parts cranially superorbitally on the upper eyelid of the left eye and in the ceiling of the orbit, lesion of the size of 40x26x18mm, in close contact with the eyeball, osteolytic, osteoplastic changes on skeleton not observed (fig. 5).

5. CT scan Patient 2 – arrow shows the lesion of MCC

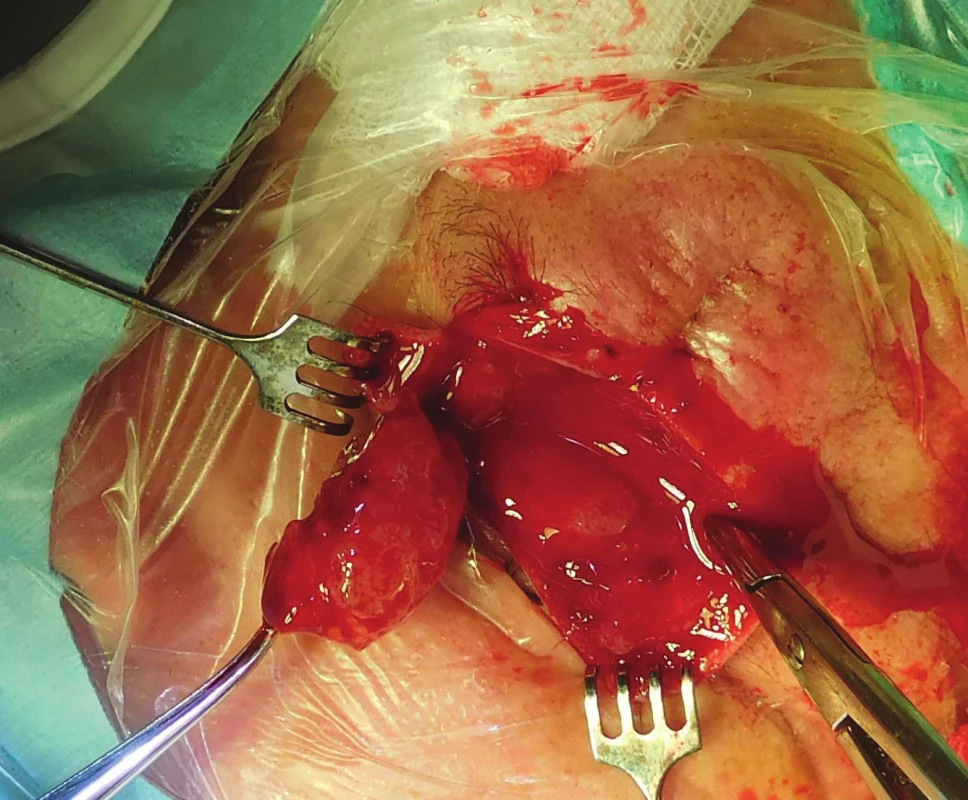

The patient was indicated for surgical solution of the tumorous mass in the region of the orbit, upper eyelid and supercilium, in May 2017 orbitotomy sup.l.sin (fig. 6). Perioperatively the volume of the tumour deposit was reduced by 5 cm3 (fig. 7).

6. Patient 2 – peroperative findings by Orbitotomy l.sin.

7. Tumor masses removed during surgery, in cut whitish, crumbly, with no case

Histopathological examination repeatedly confirmed Merkel cell carcnioma, after surgery healing p.p. i (fig. 8). The patient was sent for an oncological consultation due to extensive presence of pathological nodes supra and infradiaphragmatic, supraclavicular bilateral, also in the region of the mediastinum, periportal, pancreatic-duodenal, in mediastinum and hillum forming packets and in pulmonary parenchyma isolated subpleural and intrapulmonary nodules, recommended concomitant RT + CHT (etoposide and cisplatin). The patient tolerated the beginning of CHT and RT well, in the region of the left orbit and eyelid without local recurrence (fig. 9). Sent for CT and MRI examination (8/2017), natively in region of head and face without presence of evident tumorous lesions. The patient is continuing in therapy with etoposide and cisplatin and feels well.

8. Clinical findings of Patient 2 after surgery in May 2017

9. Patient 2 – detail of scar of upper eyelid with no recurrence of MCC in September 2017

DISCUSSION

Merkel cell carcinoma ranks among rare skin tumours. Similarly to other neuroendocrine carcinomas it manifests signs of epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation. This concerns a rare tumorous pathology of the skin, with a pronounced tendency toward local recurrence, affliction of regional nodes and the formation of remote metastases. In immunocompromised patients it mostly has a highly aggressive course and frequently a fatal outcome. This emphasises the need for regular preventive inspection of the skin in patients and the need to indicate an adequate surgical solution in the case of suspect lesions.

In the case of confirmation of MCC, the subsequent therapeutic procedures must be comprehensive and sufficiently intensive. The incidence of this pathology primarily in the region of the eyelids and surrounding area of the eye is rare, and for this reason an ophthalmologist in co-operation with a dermatologist should consider the possibility of this pathology upon every recurring, non-healing lesion in the region of the eyelids and surrounding tissues of the eye. In case of doubts it is always necessary to send a sample for histopathological examination.

The tumour occurs primarily in areas exposed to sunlight, which was also confirmed in the case of our two patients.

Histopathological differential diagnostics incorporates several malignant tumours, which include in particular small-cell malignant melanoma, skin lymphomas, certain forms of basal cell carcinoma, Ewing's sarcoma and skin metastases of small-cell carcinoma, which probably represent the greatest differential diagnostic problem in regular diagnostic practice. In the field of ophthalmology the image of the deposit on the eyelids or in the surrounding area of the eye may be mistaken for a recurring chalazion, which was confirmed also in one of our patients.

A diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma is based on the fundamental histological image of a solidly arranged tumour consisting of phenotype-primitive polygonal cells. It is always necessary to confirm the diagnosis by immunohistological examination of the signs of epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation. At present, it is recommended to examine the tumour for a panel of antibodies, which incorporate CK 20, CK 7, TTF-1, NSE and / or neurofilament, or chromogranin A. The majority of described tumours manifest positivity of NSE and neurofilament, positivity of chromgranin A is generally variable and identified only in a smaller percentage of cases. Use of the antibody MNF116 therefore appears to be beneficial in diagnostically complicated cases of MCC with a different immunohistochemical profile of CK 20 expression. The antibody MNF116 fairly faithfully copies the degree of CK 20 expression in the tumour cells [47]. Results are being produced by new observations on the expression of β-tubulin class III in neuroendocrine carcinomas [48]. A pronounced difference between the reactivity of antibodies TU-20 and tuj-1 was observed in a group of squamous cell carcinomas, which manifested positivity of β-tubulin class III upon the use of antibody tuj-1 [49], whereas upon the use of the antibody TU-20 the result was negative [50]. Another possible explanation is the known and frequent post-translation modification of the C-end of various isotypes of β-tubulin, or the interaction of this region with microtubule associated proteins (MAP), which may alter the antigenic properties of this region [51].

However, the causal role of cyclosporine in the pathogenesis of skin tumours in patients following organ transplants is disputable, and the risk of their occurrence is linked rather with the general level of immunosuppression than with a single specific immunosuppressant [52, 53]. In the case of a patient following a combined transplant of the kidney and pancreas, from the beginning, therapy was based on the administration of tacrolimus together with mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. Through conversion to sirolimus and the discontinuation of mycophenolate shortly after the determination of the diagnosis, after a few months a generalisation of the process took place [54]. The occurrence of MCC was observed also in a patient upon long-term use of azathioprine [55], and in this case also conversion to sirolimus did not prevent generalisation of the pathology. These findings support the hypothesis concerning the causal role of the general level of immunosuppression rather than a single specific immunosuppressant and also indicate the insufficient effect of reducing immunosuppression and conversion to sirolimus in influencing the further course of this pathology. In our clinical observation, MCC occurred in one patient following treatment for leukaemia.

The fundamental preventive measure remains regular examination of the skin in immunosuppressive patients, together with the performance of a biopsy in the case of a suspicious finding. The application of antiviral agents against MCPyV for positive risk patients is limited by the fact that at present, an antibody response is already present in the majority of patients, which attests to the fact that active infection took place in the period before the pathology, and active replication of the virus is not taking place. In certain patients prophylactic vaccination against MCPyV is considered, specifically for immunosuppressive patients who have not yet contracted MCPyV infection [56].

Some authors doubt the influence of primary localisation of the tumour on the general survival of patients. Similarly, doubt has been cast upon the significance of a tumour positive resection boundary and the proximity of the lesion to the regional lymphatic nodes as a predictor of the development of nodal affliction [57]. In our patients, in both cases upon probatory excision, the resection edges were not loose, and in both the biopsy was addressed only after previous surgical procedures.

It is recommended to perform wide excision of the tumour locally, because local recurrence is linked with a worse general prognosis [58]. Increased expression of apoptosis survivin andP63 is also considered prognostically negative [59].

In the prognosis of MCC, the most significant role is played by the staging of the tumour at the time of identification of the pathology, lesions localised in the area of the buttocks and torso are linked with a higher incidence of nodal metastases in comparison with lesions localised on the head and neck [58]. In our patients the metastases occurred very early, despite the fact that the primary lesion of MCC was in the facial area.

CONCLUSION

Merkel cell carcinoma in the region of the eyelids is a rare pathology. Upon the presence of remote metastases our therapeutic options are limited, and surgical solution is a palliative treatment, similarly as with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. MCC can be considered tumour-chemosensitive, but only rarely chemo-curable. The chemotherapeutic treatment protocol is subject to the recommendations valid for small-cell bronchial carcinoma. Polychemotherapy is applied with a combination of methotrexate, bleomycin, 5-fluorouracil or cyclophosphamide. An alternative to an aggressive high-dose therapeutic scheme, especially in older patients, may be the administration of etoposide in a low dose. Symptomatic treatment is important. Shortly after the surgical removal of the primary tumour, local recurrences and metastases may occur in the lymph nodes. For this reason, it is essential to ensure very thorough observation of patients within the framework of preventive care.

The authors of the study declare that no conflict of interest exists in the compilation, theme and subsequent publication of this professional communication, and that it is not supported by any pharmaceuticals company.

Delivered to the editorial board 12.3.2018

Received for printing 13.3.2018

doc. Mgr. MUDr. Alena Furdová, PhD., MPH, FEBO

Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University and Ružinov University Hospital, Bratislava

Ružinovská 6, 826 06 Bratislava

Sources

1. Allen, P.J., Bowne, W.B., Jaques, D.P., et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2005; 23 (10): 2300–9.

2. Becker, J., Mauch, C., Kortmann, R-D., et al.: Short German guidelines: Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG. 2008; 6 (Suppl 1): S15-16.

3. Becker, J.C., Houben, R., Ugurel, S. et al.: MC polyomavirus is frequently present in Merkel cell carcinoma of European patients. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009; 129 (1): 248–50.

4. Becker, J.C., Schrama, D., Houben, R.: Merkel cell carcinoma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2009; 66 (1): 1–8.

5. Boratyńska, M., Watorek, E., Smolska, D. et al.: Anticancer effect of sirolimus in renal allograft recipients with de novo malignancies. Transplant. Proc. 2007; 39 (9): 2736–9.

6. Bossuyt, W., Kazanjian, A., De Geest, N. et al.: Atonal homolog 1 is a tumor suppressor gene. PLoS Biol. 2009; 7 (2): e39.

7. Brenner, B., Sulkes, A., Rakowsky, E. et al.: Second neoplasms in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2001; 91 (7): 1358–62.

8. Brunner, M., Thurnher, D., Pammer, J. et al.: Expression of VEGF-A/C, VEGF-R2, PDGF-alpha/beta, c-kit, EGFR, Her-2/Neu, Mcl-1 and Bmi-1 in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. U. S. Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2008; 21 (7): 876–84.

9. Buell, J.F., Trofe, J., Hanaway, M.J. et al.: Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant. Proc. 2002; 34 (5): 1780–1.

10. Busse, P.M., Clark, J.R., Muse, V.V. et al.: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 19-2008. A 63-year-old HIV-positive man with cutaneous Merkel-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008; 358 (25): 2717–23.

11. Concannon, R., Larcos, G.S., Veness, M.: The impact of (18)F-FDG PET-CT scanning for staging and management of Merkel cell carcinoma: results from Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010; 62 (1): 76–84.

12. Dean, N.M., Bennett, C.F.: Antisense oligonucleotide-based therapeutics for cancer. Oncogene. 2003; 22 (56): 9087–96.

13. Dráberová, E., Lukás, Z., Ivanyi, D. et al.: Expression of class III beta-tubulin in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Histochem. Cell Biol. 1998; 109 (3): 231–9.

14. Engels, E.A., Frisch, M., Goedert, J.J. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma and HIV infection. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2002; 359 (9305): 497–8.

15. Feng, H., Shuda, M., Chang, Y. et al.: Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008; 319 (5866): 1096–100.

16. Fortina, A.B., Piaserico, S., Caforio, A.L.P. et al.: Immunosuppressive level and other risk factors for basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in heart transplant recipients. Arch. Dermatol. 2004; 140 (9): 1079–85.

17. Friedlaender, M.M., Rubinger, D., Rosenbaum, E. et al.: Temporary regression of Merkel cell carcinoma metastases after cessation of cyclosporine. Transplantation. 2002; 73 (11): 1849–50.

18. Garneski, K.M., Warcola, A.H., Feng, Q. et al.: Merkel cell polyomavirus is more frequently present in North American than Australian Merkel cell carcinoma tumors. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009; 129 (1): 246–8.

19. Girschik, J., Fritschi, L., Threlfall, T. et al.: Deaths from non-melanoma skin cancer in Western Australia. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2008; 19 (8): 879–85.

20. Goepfert, H., Remmler, D., Silva, E. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma (endocrine carcinoma of the skin) of the head and neck. Arch. Otolaryngol. Chic. Ill 1960. 1984; 110 (11): 707–12.

21. Helmbold, P., Schröter, S., Holzhausen, H.J. et al.: [Merkel cell carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge]. Chir. Z. Alle Geb. Oper. Medizen. 2001; 72 (4): 396–401.

22. Hodgson, N.C.: Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005; 89 (1): 1–4.

23. Jirásek, T., Mandys, V., Viklický, V.: Expression of class III beta-tubulin in neuroendocrine tumours of gastrointestinal tract. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2002; 40 (3): 305–10.

24. Jirásek, T., Matěj, R., Pock, L. et al.: Karcinom z Merkelových buněk – imunohistologická studie v souboru 11 pacientů. Čes.-Slov. Patol. 2009; 1 (45): 9–13.

25. Kassem, A., Schöpflin, A., Diaz, C. et al.: Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of a unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008; 68 (13): 5009–13.

26. Kim, J., McNiff, J.M.: Nuclear expression of survivin portends a poor prognosis in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. U. S. Can. Acad. Pathol. Inc. 2008; 21 (6): 764–9.

27. Koljonen, V., Kukko, H., Tukiainen, E. et al.: Incidence of Merkel cell carcinoma in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2009; 24 (10): 3231–5.

28. Krasagakis, K., Krüger-Krasagakis, S., Tzanakakis, G.N. et al.: Interferon-alpha inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of merkel cell carcinoma in vitro. Cancer Invest. 2008; 26 (6): 562–8.

29. Krejčí, K., Tichý, T., Horák, P. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation. Onkologie. 2010; 33 (10): 520–4.

30. Lawenda, B.D., Thiringer, J.K., Foss, R.D. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma arising in the head and neck: optimizing therapy. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001; 24 (1): 35–42.

31. Ludueña, R.F.: Are tubulin isotypes functionally significant. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993; 4 (5): 445–57.

32. Maubec, E., Duvillard, P., Velasco, V. et al.: Immunohistochemical analysis of EGFR and HER-2 in patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Anticancer Res. 2005; 25 (2B): 1205–10.

33. Medina-Franco, H., Urist, M.M., Fiveash, J. et al.: Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2001; 8 (3): 204–8.

34. Moosa, M.R., Gralla, J.: Skin cancer in renal allograft recipients-experience in different ethnic groups residing in the same geographical region. Clin. Transplant. 2005; 19 (6): 735–41.

35. Pastrana, D.V., Tolstov, Y.L., Becker, J.C. et al.: Quantitation of human seroresponsiveness to Merkel cell polyomavirus. PLoS Pathog. 2009; 5 (9): e1000578.

36. Pectasides, D., Pectasides, M., Economopoulos, T.: Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2006; 17 (10): 1489–95.

37. Pilotti, S., Rilke, F., Lombardi, L.: Neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1982; 6 (3): 243–54.

38. Popp, S., Waltering, S., Herbst, C. et al.: UV-B-type mutations and chromosomal imbalances indicate common pathways for the development of Merkel and skin squamous cell carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer. 2002; 99 (3): 352–60.

39. Poulsen, M., Rischin, D., Walpole, E. et al.: High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study--TROG 96 : 07. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2003; 21 (23): 4371–6.

40. Poulsen, M.G., Rischin, D., Porter, I. et al.: Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006; 64 (1): 114–9.

41. Ratner, D., Nelson, B.R., Brown, M,D. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1993; 29 (2 Pt 1): 143–56.

42. Rečková, M., Lawrence, H.E.: Nezvyčajný prípad dlhodobého prežívania pacientky s chemorefraktérnym Merkelovym karcinómom. Klin. Onkol. 2007; 20 (5): 354–6.

43. Schmid, C., Beham, A., Feichtinger, J. et al.: Recurrent and subsequently metastasizing Merkel cell carcinoma in a 7-year-old girl. Histopathology. 1992; 20 (5): 437–9.

44. Scott, C.A., Walker, C.C., Neal, D.A. et al.: Beta-tubulin epitope expression in normal and malignant epithelial cells. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1990; 116 (5): 583–9.

45. Shaw, J.H., Rumball, E.: Merkel cell tumour: clinical behaviour and treatment. Br. J. Surg. 1991; 78 (2): 138–42.

46. Sihto, H., Kukko, H., Koljonen, V. et al.: Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009; 101 (13): 938–45.

47. Smith, D.F., Messina, J.L., Perrott, R. et al.: Clinical approach to neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin (Merkel cell carcinoma). Cancer Control J. Moffitt Cancer Cent. 2000; 7 (1): 72–83.

48. Swick, B.L., Ravdel, L., Fitzpatrick, J.E. et al.: Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha mutational status and immunohistochemical expression in Merkel cell carcinoma: implications for treatment with imatinib mesylate. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2008; 35 (2): 197–202.

49. Tai, P.T., Yu, E., Tonita, J. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2000; 4 (4): 186–95.

50. Tai, P.T., Yu, E., Winquist, E. et al.: Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine/Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: case series and review of 204 cases. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2000; 18 (12): 2493–9.

51. Toker, C.: Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch. Dermatol. 1972; 105 (1): 107–10.

52. Ullrich, S.E.: Sunlight and skin cancer: lessons from the immune system. Mol. Carcinog. 2007; 46 (8): 629–33.

53. Ullrich, S.E.: Mechanisms underlying UV-induced immune suppression. Mutat. Res. 2005; 571 (1–2): 185–205.

54. Van Keymeulen, A., Mascre, G., Youseff, K.K. et al.: Epidermal progenitors give rise to Merkel cells during embryonic development and adult homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 2009; 187 (1): 91–100.

55. Veness, M.J., Harris, D.: Role of radiotherapy in the management of organ transplant recipients diagnosed with non-melanoma skin cancers. Australas. Radiol. 2007; 51 (1): 12–20.

56. Veness, M.J., Morgan, G.J., Gebski, V.: Adjuvant locoregional radiotherapy as best practice in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2005; 27 (3): 208–16.

57. Walsh, N.M.: Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum. Pathol. 2001; 32 (7): 680–9.

58. Weller, K., Vetter-Kauzcok, C., Kähler, K. et al.: Guideline Implementation in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: An Example of a Rare Disease. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2006; 103: A 2791–6.

59. Yiengpruksawan, A., Coit, D.G., Thaler, H.T. et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma. Prognosis and management. Arch. Surg. Chic. Ill 1960. 1991; 126 (12): 1514–9.

Labels

Ophthalmology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Ophthalmology

2018 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit

- Change of tear osmolarity after refractive surgery

- Optic nerve orbital meningioma

- Pachychoroid disease of the macula

- Femtosecond Laser - assisted intrastromal corneal segment implantation - our experience

- Use of ex-press® implant in glaucoma surgery - retrospective study

- Czech and Slovak Ophthalmology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Pachychoroid disease of the macula

- Optic nerve orbital meningioma

- Use of ex-press® implant in glaucoma surgery - retrospective study

- Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career