-

Medical journals

- Career

Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

Authors: Manjunath N. K.; Waiker V. P.; Shanthakumar S.; Kumaraswamy M.

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Ramaiah Medical College, Bangalore, India

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 64, 1, 2022, pp. 6-11

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp20226Introduction

Anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap was first described by Song et al [1]. Since then, it has gained popularity as a free microvascular flap and currently it is the workhorse flap for soft tissue reconstruction in several regions of the body. Its flexibility follows from its long vascular pedicle, ability to use different tissues in composite nature, large size of skin paddle and minimal donor site morbidity [2]. The blood supply to the skin paddle of ALT flap is by septo-cutaneous or musculocutaneous perforators, which arise from the descending branch of lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA). The utilization of free ALT flap for soft tissue reconstruction in various regions of the body is well known [3]. However, reconstruction of in-depth onco-surgical defects of the lower trunk, perineum and upper thigh without the complexity of microsurgery may sometimes be a reconstructive challenge [4]. In those situations, pedicled ALT flap offers many advantages over other regional flaps [4]. However, it is less commonly reported [2]. The vascular pedicle of this flap (the descending branch of LCFA) passes through the septum between vastus lateralis muscle and rectus femoris muscle, towards the knee and anastomoses with lateral superior genicular artery or the profunda femoris artery perforators. Hence, ALT flaps are often harvested based on its proximal circulation or the distal circulation. This property, alongside the long vascular pedicle, are often utilized to hide the varied soft tissue defects involving the abdomen, groin, perineum, and trochanteric regions proximally (proximally based circulation), and soft tissue defects around the knee distally (distally based circulation) [5]. Since pedicled ALT flap has many advantages and there is less literature regarding an equivalent, this study is undertaken to spotlight the usefulness of the pedicled ALT flap. This study aimed to review the efficacy of pedicled ALT flap in reconstruction of the regional defects.

Its objectives are to determine the efficiency of ALT flap in terms of the area of coverage, arc of rotation and therefore the distal reach of the flap and to determine the benefits of harvesting vastus lateralis muscle as a part of the flap.

Materials and methods

A retrospective record analysis of all pedicled ALT flaps from 2016 to 2018 was undertaken. Seven patients with 8 defects of the thigh, groin, gluteal and lower abdominal region requiring flap coverage were included in the study. Patients’ demographic details like age, sex, site of the defect are noted. The details of the flap harvested are documented (laterality, size of the flap, island or the peninsular). While abstracting the details from the records, personal details like name, address etc. were not retrieved.

Operative technique

Under suitable anesthesia, patient was put in a supine position with a 20° medial rotation of the hip. Ipsilateral anterior superior iliac spine and supero-lateral border of the patella were marked. The line joining these points marked the intermuscular septum between vastus lateralis and rectus femoris muscle. The flap was designed keeping this line as the central meridian (Fig. 1). An anterior incision was made and deepened till the intermuscular septum and any septo-cutaneous perforators were preserved. A flap was harvested alongside the vastus lateralis muscle. The vascular pedicle was dissected proximally up-to-the origin at the lateral circumflex femoral vessels. Depending on the recipient site requirement, the vastus lateralis muscle was either separated as a chimera or used to fill the depth of the defect. The flap was completely islanded and inset into the defect. The donor site was closed primarily or with skin grafts.

Fig. 1. Anterolateral thigh flap marking.

Follow-up and outcome measures

The patients were followed up for immediate and late complications. Immediate complications like partial or complete loss of flap and minor complications like gapping of the wound, seroma, hematoma, and wound infections were studied. Late complications like recurrence of pressure sore, donor site scar and gait abnormalities (in ambulant patients) were studied on follow-up. The outcome of the flap was analyzed in terms of the area of the defect covered, arc of rotation and distal reach of the flap. The use of the vastus lateralis muscle with the flap was also analyzed.

Results

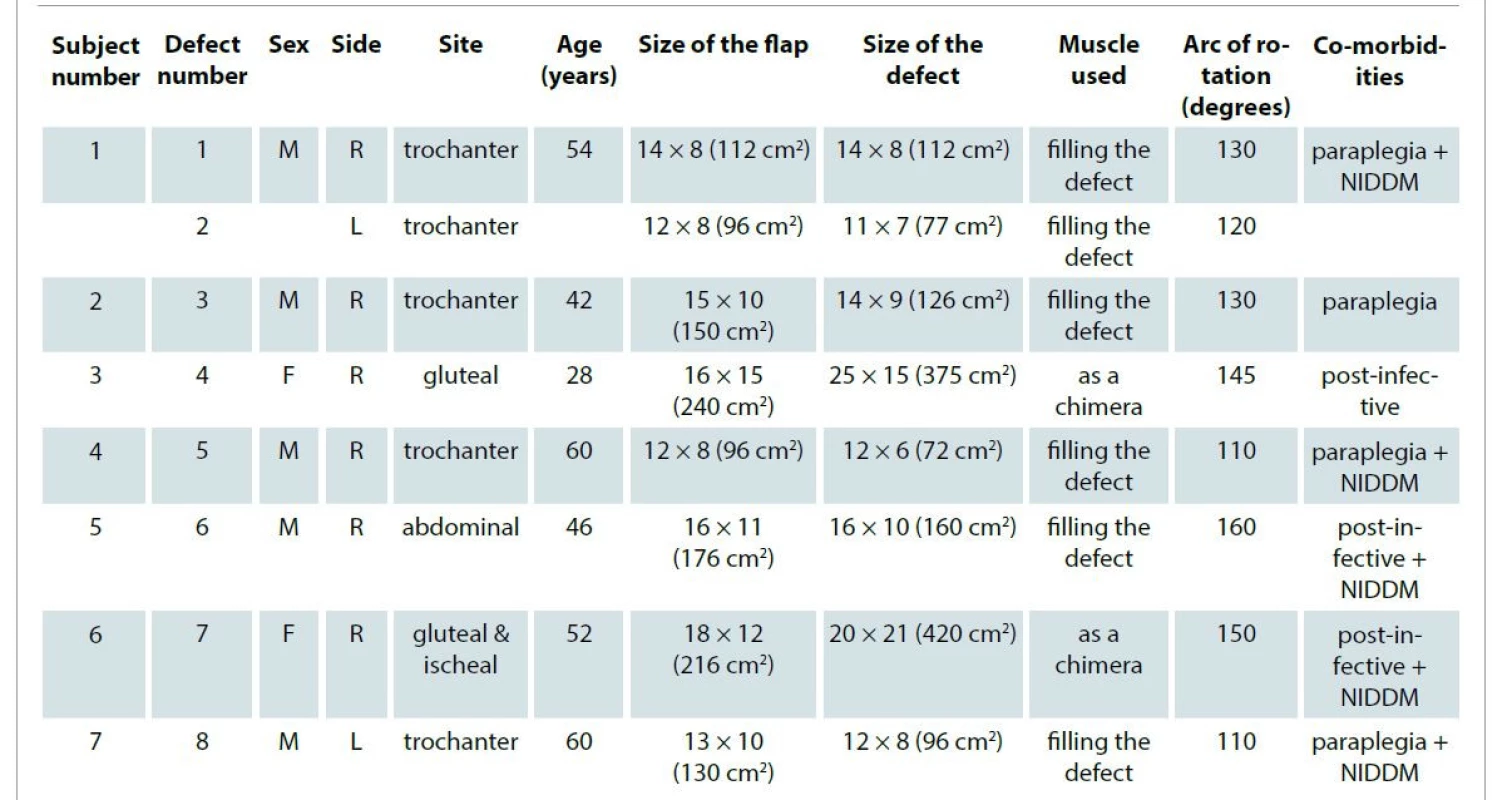

In our study, 7 patients with 8 defects were treated with a pedicled ALT flap. Out of these patients, 5 (71.4%) were males and 2 were females (28.6%). The age of the patients was 28–62 years. Among the 8 defects, 5 (62.5%) were in the trochanteric region, and 1 (12.5%) each in the gluteal, ischial and abdominal regions. The mean size of the defect was 179.75cm2 (72 cm2 was the least size and 420 cm2 was largest). Overall, 152cm2 was the mean size of the skin paddle. In 2 cases with large defects, the skin paddle and the vastus lateralis muscle were separated and used as a chimeric flap. The muscle component was resurfaced with skin grafts. Four out of 7 (42.85%) patients were paraplegic and 5 had non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus as a comorbidity (Tab. 1). All flaps were successful. There was no partial or complete loss of the flap. Minor complications like wound gapping and hematoma were found in three patients. These were managed conservatively. There was no recurrence of the bedsore at one-year follow-up. The donor site scar was well settled in all patients. Ambulant patients did not have any functional deficit of gait. The complications and therefore the comorbidities were not statistically significant.

1. Demographic profile of the patients.

F – female, M – male, L – left, R – right, NIDDM – non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus Discussion

ALT flap was described for the first time in 1984 [2]. Recently, ALT has been a popular flap among the reconstructive surgeons thanks to its various advantages [2]. The skin territory of the ALT flap has not been defined even today. However, in studies, more than half of the circumference of thigh [6] has been successfully harvested without any flap necrosis. Since the circumference of the thigh is a subjective measure, depending on the individual’s physical habitus, large skin flaps can be harvested. This is a great potential for any flap donor site (Fig. 2A–C) [6]. Since the donor area is huge, large fascio-cutaneous flaps can be harvested from the thigh. In our study, the size of the largest flap harvested was 16 x 15 cm (240 cm2) (Fig. 3A, B). In the study conducted by Friji et al, the size of the largest flap harvested was 38 x 20 cm (760 cm2) [4]. In a Chinese study done by Chin et al, the largest flap harvested was 11 x 18 cm (198 cm2) in size [7]. In another study by Mojtaba [8], the size of the largest flap was 380 cm2. In all studies, there were no major complications and the flaps survived completely. However, the different size of the flap can be explained by the fact that physical stature of the patient has an impact on the flap size harvested. Even in our study, the flaps from size 12 x 6 (72cm2) to 16 x 15 cm (240 cm2) were successful without any major complications. Many factors contribute to this enormous capacity of the vascular pedicle to supply large flaps. Ligation of the muscular branches led to increased blood flow to the fasciocutaneous perforators and denervation causes increased flow due to loss of sympathetic tone [9]. Also, opening up the choke vessels in adjacent angiosomes helped to increase dimensions of the flap. Whenever the skin component is deficit, a flap can be harvested along with the vastus lateralis muscle as a chimeric flap (Fig. 4A–C) [10,11]. The separate vascular pedicle to fasciocutaneous and muscle components gives freedom for the operating surgeon to plan large flaps and to increase the distal reach of the flap [12]. The other major advantage of harvesting the vastus lateralis muscle as a musculocutaneous flap is the use of a muscle component to fill the cavity of the defects. In all our flaps muscle was harvested along with the fasciocutaneous component. This also reduced the flap harvest time as the dissection of the skin perforators through the muscle was avoided. Moreover, this procedure increased the vascularity of the overlying skin component [13] through musculocutaneous perforators; large flaps could be harvested with adequate reliability there. The muscle also provided plentiful vascularity to the recipient area and mopped up the infection [6] contributing to a faster healing of the wound. In two of our cases, the muscle was used as a chimeric flap and used to cover large gluteal defects. The vastus lateralis chimeric flap was used for reconstruction [14] and recommended as a first line reconstructive option for the defects following the excision of advanced and recurrent malignancies. Pedicled ALT with a vastus lateralis muscle flap was a good alternative to a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap for large defects associated with pelvic exenteration [15]. In these cases, the dead space could be obliterated by the bulk of the flap and vagina, the perineum could be reconstructed sparing the integrity of the abdominal wall. The descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery runs along the septum from the upper third of the thigh till the knee region. Along its course, it gives many muscular as well as septo-cutaneous branches. The pedicle of the ALT flap is known to be advantageous thanks to its length. Zelken et al [15] reconstructed the mutilated hand injuries using pedicled ALT flaps together with a groin flap. In this study, ALT was used as an alternative to an abdominal flap. Vascular supply of the ALT flap is provided from these septo-cutaneous or musculocutaneous perforators [15–18]. The length of the pedicle depends upon the skin perforator selected [6]. In a situation when a greater length of a pedicle is needed, the length can be further increased by ligation of the muscular branches and continuing dissection till the origin of the descending branch (Fig. 5) [19]. As majority of our flaps were harvested along with the muscle, the position of the skin perforator was not determined pre-operatively. Dissection of the skin perforator through the muscle is one of the time-consuming parts. In our study, since the muscle was harvested along with skin, this reduced the harvest time drastically [8].

Fig. 2. Right trochanteric pressure sore. A) Preoperative state; B) intraoperative state; C) postoperative state.

Fig. 3. Left trochanteric pressure sore. A) Preoperative state; B) postoperative state.

Fig. 4A. Right gluteal defect after thorough debridement.

Fig. 4B. After insetting of the vastus lateralis and anterolateral thigh chimeric flap.

Fig. 4C. One-month follow-up state.

Fig. 5. Pedicle dissection till the lateral circumflex iliac artery.

The minimum arc of rotation was 110° and the maximum was 160° in our study. The distal end of the flap reached upto umbilical region when transferred cranially and reached the mid line, covering the gluteal region when rotated posteriorly.

In the islanded flap, the position of the lateral circumflex femoral artery was the pivot point. The extent of the dissection of the pedicle and the position of the skin perforator determined the arc of rotation [2]. In some studies, pedicled ALT flap were used to cover defects as high as epigastrium [20–23]. The authors suggested that if the most distal skin perforator is selected, the reach can be maximal [24]. In another study by Koustic et al, the reach of pedicled ALT was 360°, 180° clockwise and 180° anti-clockwise [14]. They also suggested choosing the most distal skin perforator to maximize rotation of the flap without tension. They also concluded that if the vastus lateralis is also harvested as a chimera flap, the flap had large dimensions and wide arc of rotation.

Apart from these advantages, ALT flap has the least donor site morbidity. In majority of our patients, a primary closure was possible and few of them needed small skin grafts to cover the remaining area. Since the vastus lateralis was harvested in all cases, primary closure was much easier [14]. The donor site is in the concealed area and did not have any esthetic concern [6]. Although the majority of our patients were paraplegic, three were ambulant patients and they had no functional deficit even after muscle harvest. With so many advantages, a pedicled ALT flap is an ideal flap for loco-regional defects, especially in patients who need a large flap for reconstruction and cannot tolerate long operating times.

Conclusion

The ALT flap has been termed as the best free flap option for reconstruction since the time of its description. However, its pedicled counterpart has not been popular. The literature regarding the pedicled ALT, musculocutaneous flap and the chimeric flap is very limited. In our institutional experience, we could conclude that a pedicled ALT has many advantages. The ALT-vastus lateralis

myocutaneous flap dimension can be large and harvested easily in very short duration. The harvested vastus lateralis muscle can be used to fill the defect or as a chimera to cover the defect. Moreover, the use of muscle over long-standing infective pressure sores can sterilize the wound bed and help preventing recurrence. The vascularity of this flap is robust and highly reliable. Even after the maximum arc of rotation (up to 170°), all the flaps survived without any major complications. Hence, a pedicled ALT flap is equally advantageous as its microvascular counterpart. We highly recommend its use, especially in the elderly and frail patients requiring large wound reconstruction in a shorter operating time.

Role of authors: All authors have been actively involved in the planning, preparation, analysis and interpretation of the findings, enactment and processing of the article with the same contribution.

Declaration: All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as amended in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study. The study has been approved by the institutional ethical committee. The ethical committee approval number is SS/EC/24/2020.

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Dr. Manjunath K. N.

Department of plastic and

reconstructive surgery

Ramaiah Medical College

Bangalore

India

e-mail: drknmanjunath@gmail.com

Submitted: 22. 9. 2021

Accepted: 23.1. 2022

Sources

1. Song YG., Chen GZ., Song YL. The free thigh flap: a new free flap concept based on the septocutaneous artery. Brit J Plastic Surgery. 1984, 37(2): 149–159.

2. Naalla R., Chauhan S., Bhattacharyya S., et al. The versatility of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap: a tertiary referral center experience from India. Int Microsurgery Journal. 2017, 1(2): 5.

3. Nambi GI., Salunke AA., Chung S., et al. Extended anterolateral thigh pedicled flap for reconstruction of trochanteric and gluteal defects: a new & innovative approach for reconstruction. Chin J Traumatol. 2016, 19(2): 113–115.

4. Friji MT., Suri MP., Shankhdhar VK., et al. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flap: a versatile flap for difficult regional soft tissue reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010, 64(4): 458–461.

5. Gravvanis AI., Tsoutsos DA., Karakitsos D., et al. Application of the pedicled anterolateral thigh flap to defects from the pelvis to the knee. Microsurgery. 2006, 26(6): 432–438.

6. Bahk S., Rhee SC., Cho SH., et al. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flaps for reconstruction of recurrent trochanteric pressure ulcer. Arch Reconstr Microsurg. 2015, 24(1): 32–36.

7. Lin CT., Wang CH., Ou KW., et al. Clinical applications of the pedicled anterolateral thigh flap in reconstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2017, 87(6): 499–504.

8. Ghods M., Kruppa P., Thiels K., et al. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flaps and their use in abdominal wall reconstruction: a case series. Adv Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018, 2(4): 225–229.

9. Saint-Cyr M., Uflacker A. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for complex trochanteric pressure sore reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012, 129(2): 397e–399e.

10. Gedebou TM., Wei FC., Lin CH. Clinical experience of 1284 free anterolateral thigh flaps. Handchir Mikrochir Plast. 2002, 34(4): 239–244.

11. Hallock GG. The proximal pedicle anterolateral thigh flap for lower limb coverage. Ann Plast Surg. 2005, 55(5): 466–469.

12. Lin YT., Lin CH., Wei PC. More degrees of freedom by using chimeric concept in the applications of anterolateral thigh flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006, 59(6): 622–627.

13. Posch NA., Mureau MA., Flood SJ., et al. The combined free partial vastus lateralis with anterolateral thigh perforator flap reconstruction of extensive composite defects. Br J Plast Surg. 2005, 58(8): 1095–1103.

14. Kosutic D., Muth R., Apostolos V., et al. 3600 of freedom in chimeric pedicled vastus lateralis-ALT perforator flap for reconstruction in patients with advanced or recurrent malignancies. Clin Surg. 2017, 2 : 1401.

15. Wong S., Garvey P., Skibber J., et al. Reconstruction of pelvic exenteration defects with anterolateral thigh-vastus lateralis muscle flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009, 124(4): 1177–1185.

16. Vranckx JJ., D’Hoore A. Reconstruction of perineum and abdominal wall. In: Danilla S. (eds). Selected Topics Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012, 141–158.

17. Walia GS., Broyles JM., Christensen JM., et al. Pedicled anterolateral thigh flaps for salvage reconstruction of complex abdominal wall defects. Clin Surg. 2017, 2 : 1298.

18. Bradow O. Fundamentals of perforator flaps. In: Janis J., Good A., Taylor S. Essentials of plastic surgery. Boka Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group 2014 : 51.

19. Burm JS., Yang WY. Distally extended tensor fascia lata flap including the wide iliotibial tract for reconstruction of trochanteric pressure sores. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011, 64(9): 1197–1201.

20. Ting J., Trotter D., Grinsell D. A pedicled anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap for reconstruction of the epigastrium. Case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010, 63(1): e65–67.

21. Fernandez-Alvarez JA., Barrera-Pulido F., Lagares-Borrego A., et al. Coverage of supraumbilical abdominal wall defects: the tunnelled-pedicled ALT technique. Microsurgery. 2017, 37(2): 119–127.

22. Sacks JM., Broyles JM., Baumann DP. Flap coverage of anterior abdominal wall defects. Semin Plast Surg. 2012, 26(1): 36–39.

23. Nthumba P., Barasa J., Cavadas PC., et al. Pedicled fasciocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap for the reconstruction of a large postoncologic abdominal wall resection defect: a case report. Ann Plast Surg. 2012, 68(2): 188–189.

24. Maxhimer JB., Hui-Chou HG., Rodriguez ED. Clinical applications of the pedicled anterolateral thigh flap in complex abdominal-pelvic reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2011, 66(3): 285–291.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2022 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome after surgery – a case control study

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Development of a questionnaire for a patient-reported outcome after nasal reconstruction

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Emergency evacuation low-pressure suction for the management of extravasation injuries – a case report

- Editorial

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career