-

Medical journals

- Career

Supraclavicular artery island flap for head and neck reconstruction

Authors: Bayram Ahin 1; Murat Ulusan 2; Bora Aran Ba 2; Selcuk Güne 3; Emre Oymak 1; Selahattin Gen 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, Kocaeli Health Sciences University Derince Training and Re-search Hospital, Kocaeli, Turkey 1; Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, Istanbul Medical Faculty, University of Istanbul, Istanbul, Turkey 2; Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, Memorial Hizmet Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey 3

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 63, 2, 2021, pp. 52-56

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp202152Introduction

The objectives of the reconstruction of head and neck defects should include provision of vascularized tissue support for complex defects, and functional and cosmetic restoration of three-dimensional anatomical structures. Microvascular free flaps are the first treatment option to achieve these goals according to current medical guidelines [1,2]. However, free tissue transfers require proper vascular structure and neck anatomy, microvascular anastomosis expertise, prolonged surgery times and intensive care unit monitoring following surgery. For these reasons, the usage of free tissue flaps may not be possible in every patient. Local flaps are usually not suitable for the repair of large surgical defects while pedicled regional flaps are bulky and have some disadvantages, such as significant donor-site morbidity, functional problems and aesthetic incompatibility.

The supraclavicular artery island flap (SCAIF) is a fasciocutaneous pedicled flap based on the supraclavicular artery, a branch of the transverse cervical artery, first described by Lamberty and Cormack [3] in 1983. In the 1990s, Pallua et al. [4] popularized this flap for the reconstruction of postburn mentosternal contractures. Subsequently, Chiu et al. [5] reported for the first time that the supraclavicular flap can be used for head and neck reconstruction following an oncologic surgery. The use of SCAIF in the reconstruction of head and neck defects has become popular in recent years, especially being utilized in defects of the lower third of the face and neck [6].

The aim of this study was to investigate the indications, both functional and cosmetic outcomes and complications of the SCAIF as well as its reliability as an alternative to free tissue transfer for moderate to large defects of the head and neck area.

Material and methods

Patients selection

This retrospective clinical study was carried out at two different tertiary referral hospitals (Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery) through the utilization of patient records taken between January 2017 and December 2020. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee. All phases of the study were conducted in line with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

A total of 19 patients who underwent head and neck reconstruction with SCAIF were included in this study. All surgical procedures were performed by head and neck surgeons. The demographic features of the patients, regions of the surgical defects, flap harvesting times, histopathological subtypes and localization of the cancer, postoperative complications and wound problems of all patients were obtained from the patients’ medical records. The SCAIF was used for the reconstruction of oncological defects in 17 patients, for the reconstruction of a skin defect on the lower face following radiotherapy in 1 patient and for cervical open wound (blast injury) closure in 1 patient.

Surgical technique

The patient was placed in a supine position and a pillow was put under the patient’s shoulder. The patient’s neck was brought into an extension position and the head was rotated to the opposite side of the flap donor site. The possible origin point of the supraclavicular artery was marked in a triangular region, which was delimited by sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, by clavicle inferiorly and by the external jugular vein posteriorly (Fig. 1A). The flap was designed according to the size, shape and localization of the surgical defect in an area defined by the anterior border of the trapezius muscle posteriorly and by the line parallel to the deltoid muscle fibers anteriorly (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. (A) Determination of the possible origin of the supraclavicular artery via anatomical landmarks. (B) Elevation of the flap from the distal to the proximal over the deltoid muscle. (C) Completion of the flap elevation up to its most proximal portion, where the supraclavicular artery originates from the transverse cervical artery. (D) Performance of skin de-epithelization of the flap after completion of flap harvesting (straight white arrows - anterior border of the trapezius muscle; dashed white arrows - clavicle; straight black arrows - inferior border of the deltoid muscle; dashed black arrow - surgical defect area; asterisk - deltoid muscle; arrow heads - trapezius muscle).

After the completion of the skin, subcutaneous tissue and fascial incisions, the fascia was sutured to the skin by a 4-0 polyglactin suture (Vicryl®, Ethicon© Inc, Johnson & Johnson, Sommerville, NJ). The flap was raised from the distal to the proximal (Fig. 1B). The flap elevation was performed in a subfascial plane just superficial to the deltoid muscle up to the clavicle and subperiosteal dissection was carried out on the clavicle. The flap was raised to its most proximal portion, where the supraclavicular artery originated from the transverse cervical artery (Fig. 1C). During these surgical maneuvers, the supraclavicular artery and vein were kept in mind but they were not dissected in the supraclavicular fossa. After completion of the flap harvesting, skin de-epithelization was performed on the proximal part of the flap in most patients and the flap was tunneled under the skin of the neck (Fig. 1D). Then, the flap was simply rotated or transposed to the surgical defect area for cervical and facial skin or pharyngeal reconstruction (Fig. 2A). The flap donor sites were closed primarily (Fig. 2B) following undermining of the skin edges and drainage tube placement in all patients.

Fig. 2. (A) Intraoperative view of the reconstruced surgical defect area, which includes skin and soft tissue defects of the anterior neck. (B) Postoperative view of the flap donor area, which was successfully closed primarily without any tension.

Results

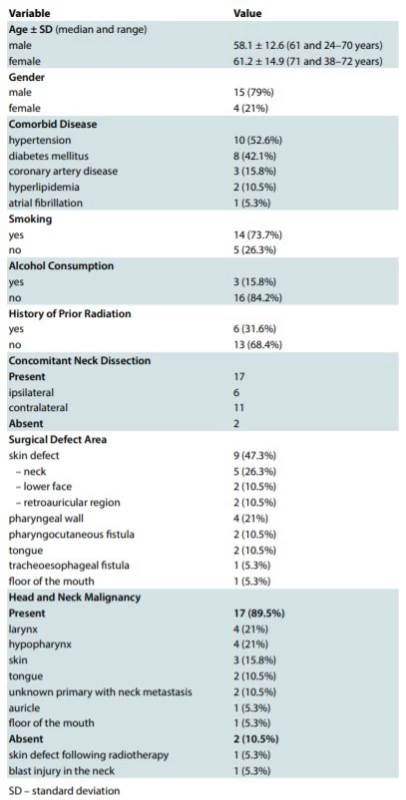

There were 15 male (79%) and 4 female (21%) patients of the average age 58.94 ± 12.89 (median: 63; range: 24–72) years. The mean follow-up time was 22.68 ± 6.18 (median: 23; range: 12–36) months. Patients’ characteristics such as demographics, comorbid diseases, smoking status, alcohol consumption, surgical indication and defect area as well as other details were summarized in Tab. 1.

The SCAIF has been utilized successfully in 18 of 19 patients for head and neck reconstructive surgery. There were neither intraoperative nor postoperative major complications in any patient. Partial necrosis of the skin was detected in 1 patient (5.3%) only, while a total flap failure has not occurred in any patient. In this patient, the flap has been used for the reconstruction of the auricle and skin of the temporal region. The partial skin necrosis was seen in an area of 1.5 cm of the distal end of the flap and was managed conservatively with local wound care.

Wound dehiscence has not appeared in the flap donor area in any patient. However, partial dehiscence has occurred between the flap recipient area and flap skin in 1 patient (5.3%) with oral cavity reconstruction. Wound edges were sutured by horizontal mattress sutures under local anesthesia. However, neck exploration and re-suturing was performed in 1 patient (5.3%) due to pharyngocutaneous fistula recurrence.

The mean flap harvesting time was 42.8 ± 6.5 minutes and the intraoperative blood loss was less than 50 mL. A closed suction drain was placed in the flap donor area and it was removed when drainage dropped to 30 mL or less. In 3 patients who underwent tongue and mouth floor reconstruction, the tracheostomy tube was placed for airway safety. The tracheostomy tube was removed 72 hours after the surgery in these patients.

Discussion

We have successfully applied the SCAIF to different surgical defects and found that this flap is reliable and easy to harvest, and is associated with low morbidity. It has also appropriate color and texture distribution with head and neck skin. This study supports a suggestion that the SCAIF may provide similar functional and cosmetic outcomes compared to free tissue transfers but requires less operative time, surgical effort and perioperative care.

The SCAIF has numerous favorable characteristics for the head and neck reconstructive surgeons. First, the SCAIF is a thin and hairless flap and has optimal aesthetic concordance with the skin of the head and neck region. Second, it is close to the head and neck region compared to pedicled flaps, such as pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi flaps, providing a better rotation arc. Third, being a flap of axial pattern, its blood supply is sufficient and reliable. Additionally, the flap can be used for oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and cervical and facial skin reconstruction with good functional and cosmetic outcomes due to its high versatility [5,7–15]. These features make the SCAIF one of the optimal treatment choices of reconstructive surgery of the head and neck.

The main disadvantage of the SCAIF is partial skin necrosis, which may develop on the most distal portion of the flap. Kokot et al. [11] reported that a flap length longer than 22 cm is significantly associated with distal tip necrosis. However, in this study, the relationship between the flap length and flap necrosis was not significant. For neopharyngeal or pharyngoesophageal reconstruction, the most distal part of the flap has a critical importance and is responsible for repairing the surgical defect. During flap harvesting, the elevation of the flap until a point 5 cm away from the last place where doppler flow was detected, which is usually located over the inferior border of the deltoid muscle, may prevent distal flap necrosis [6]. Nthumba [16] declared the rate of partial and total flap necrosis to be 6.9% and 1.4%, respectively, in his series of 349 patients. The partial flap necrosis ratio has been found to be 14.9% in another study, which includes 47 patients with advanced head and neck cancer [9]. Wang et al. [15] used the SCAIF and sternohyoid muscle combination for the reconstruction of laryngeal or hypopharyngeal defects. They did not observe partial or total flap necrosis in any patient. Teixeira et al. [6] reported a 100% rate of flap survival in 6 patients undergoing pharyngocutaneous or tracheoesophageal fistula closure. Pabiszczak et al. [17] and Li et al. [18] notified this ratio for pharyngocutaneous fistula repair as 84% and 100%, respectively. In our series, partial flap necrosis was detected in 1 patient (1/19, 5.3%) only, while total flap necrosis was not seen in any patient.

Donor site complications of the SCAIF are minimal and most of them tolerable for many patients. Seroma formation or wound dehiscence frequency has been described as 0–15% during the perioperative period [5,19]. Pallua and Magnus Noah [20] reported that the primary closure of the donor site can be performed for flaps up to 16 cm wide. On the other hand, Alves et al. [9] stated that all donor sites were primarily closed without any complications, although some of them were 12 cm wide. However, Martins de Carvalho et al. [21] suggested that the flaps wider than 7 cm require skin grafting. A closure under tension is strongly related to a high risk of wound dehiscence and unexpected scar formation development. Therefore, split thickness skin grafts or local flaps should be used for the closure of a larger donor site. Limitation of shoulder movements can be seen in some patients but this has no significant impact on daily life for them [19]. In our study, the biggest flap was 10 cm wide, and the flap donor area was closed without any problems in all subjects while wound dehiscence was not detected in any patient.

The supraclavicular artery may be identified with a hand-held Doppler or computed tomography angiography of the neck preoperatively. Some authors have utilized a hand-held Doppler to identify the origin of the supraclavicular artery before the surgical procedure [6,11,12,18,22,23]. The concomitant ipsilateral neck dissection or history of previous neck dissection is a relative contraindication for the SCAIF due to the risk of injury of the supraclavicular vessels. In spite of this, this flap was applied in our study successfully in 6 patients who underwent ipsilateral neck dissection without any complication. In our experience, if transverse cervical vessels are preserved in level 4 during neck dissection and surgical maneuvers are performed carefully in both level 4 and 5, the SCAIF can be used safely. We believe that the intraoperative doppler ultrasonography is not routinely necessary except for patients with previously ipsilaterally neck dissection history.

There are some limitations of this study such as retrospective design, lack of control group and relatively small sample size. Further prospective and multicenter studies comparing the SCAIF and both pedicled and microvascular free flaps are needed.

Conclusions

The supraclavicular artery island flap is a thin, reliable and technically simple fasciocutaneous flap that has low complication rate and provides single-stage reconstruction of the numerous surgical defects of the head and neck. The SCAIF constitutes a good alternative to free flaps, while providing almost equivalent functional results and requiring less operative time and surgical effort.

Roles of authors: All authors have been actively involved in the planning, preparation, analysis and interpretation of the findings, enactment and processing of the article with the same contribution.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Information: No financial supporter of this study.

Bayram Şahin, MD

Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery

Kocaeli Health Sciences University Derince Training and Research Hospital

İbni Sina Mah. Lojman Sok. Derince/Kocaeli, Turkey, 41090

e-mail: drbayramsahin@gmail.com

Submitted 29. 03. 2021

Accepted 09. 05. 2021

Sources

- Sukato DC., Timashpolsky A., Ferzli G., et al. Systematic review of supraclavicular artery island flap vs free flap in head and neck reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019, 160: 215–222.

- Gurtner GC., Evans GRD. Advances in head and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000, 106: 672–683.

- Lamberty BG., Cormack GC. Misconceptions regarding the cervico-humeral flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1983, 36: 60–63.

- Pallua N., Machens HG., Rennekampff O., et al. The fasciocutaneous supraclavicular artery island flap for releasing postburn mentosternal contractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997, 99: 1878–1884.

- Chiu ES., Liu PH., Friedlander PL. Supraclavicular artery island flap for head and neck oncologic reconstruction: indications, complications, and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009, 124: 115–123.

- Teixeira S., Costa J., Monteiro D., et al. Pharyngocutaneous and tracheoesophageal fistula closure using supraclavicular artery island flap. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275: 1921–1926.

- Kim RJT., Izzard ME., Patel RS. Supraclavicular artery island flap for reconstructing defects in head and neck region. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011, 19: 248–2450.

- Sandu K., Monnier P., Pasche P. Supraclavicular flap in head and neck reconstruction: experience in 50 consecutive patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 269: 1261–1267.

- Alves HR., Ishida LC., Ishida LH., et al. A clinical experience of the supraclavicular flap used to reconstruct head and neck defects in late-stage cancer patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012, 65: 1350–1356.

- Granzow JW., Suliman A., Roostaeian J., et al. The supraclavicular artery island flap (SCAIF) for head and neck reconstruction: surgical technique and refinements. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013, 148: 933–940.

- Kokot N., Mazhar K., Reder LS., et al. The supraclavicular artery island flap in head and neck reconstruction. Applications and limitations. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013, 139: 1247–1255.

- Giordano L., Bondi S., Toma S., et al. Versatility of the supraclavicular pedicle flap in head and neck reconstruction. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014, 34: 394–398.

- Anand AG., Tran EJ., Hasney CP., et al. Oropharyngeal reconstruction using the supraclavicular artery island flap: a new flap alternative. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012, 129: 438–441.

- Welz C., Canis M., Schwenk-Zieger S., et al. Oral cancer reconstruction using the supraclavicular artery island flap: comparison to free radial forearm flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017, 75: 2261–2269.

- Wang Q., Chen R., Zhou S. Successful management of the supraclavicular artery island flap combined with a sternohyoid muscle flap for hypopharyngeal and laryngeal reconstruction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019, 98: 17499.

- Nthumba PM. The supraclavicular artery flap: a versatile flap for neck and orofacial reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012, 70: 1997–2004.

- Pabiszczak M., Banaszewski J., Pastusiak T., et al. Supraclavicular artery pedicled flap in reconstruction of pharyngocutaneous fitulas after total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Pol. 2015, 69: 9–13.

- Li C., Chen W., Lin X., et al. Application of the supraclavicular artery island flap for fistulas in patients with laryngopharyngeal cancer with prior radiotherapy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020 Aug 25: 145561320951678.

- Herr MW., Bonanno A., Montalbano LA., et al. Shoulder function following reconstruction with the supraclavicular artery island flap. Laryngoscope. 2014, 124: 2478–2483.

- Pallua N., Magnus Noah E. The tunneled supraclavicular island flap: an optimized technique for head and neck reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000, 105: 842–851; discussion 852-854.

- de Carvalho FM., Correia B., Silva Á., et al. Versatility of the supraclavicular flap in head and neck reconstruction. Eplasty. 2020, 20: 45–52.

- Karabulut B. Supraclavicular flap reconstruction in head and neck oncologic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2020, 31: 372–375.

- Thompson A., Khan Z., Patterson A., et al. Potential benefits from the use of the supraclavicular artery island flap for immediate soft-tissue reconstruction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2020, 19: 1–6.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2021 Issue 2-

All articles in this issue

- Editorial

- Long-term donor-site morbidity after thumb reconstruction with twisted-toe technique

- Supraclavicular artery island flap for head and neck reconstruction

- Free tensor fascia lata flap – a reliable and easy to harvest flap for reconstruction

- Presence of circulating tumor cells in a patient with multiple invasive basal cell carcinoma - a case report

- Pyoderma gangrenosum: a rare complication of reduction mammaplasty – a case report

- Negative pressure therapy in the orofacial region in oncological patients – two case reports

- Thirty-five years of the Department of Plastic Surgery and Burns Treatment at the University Hospital in Hradec Králové

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Pyoderma gangrenosum: a rare complication of reduction mammaplasty – a case report

- Free tensor fascia lata flap – a reliable and easy to harvest flap for reconstruction

- Supraclavicular artery island flap for head and neck reconstruction

- Long-term donor-site morbidity after thumb reconstruction with twisted-toe technique

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career