-

Medical journals

- Career

Securing intraoral skin grafts to the floor of the mouth: case report and technique desription

Authors: E. M. Kenny 1; F. M. Egro 1; M. G. Solari 1,2

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Plastic Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 1; Department of Otolaryngology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA 2

Published in: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 60, 1, 2018, pp. 22-25

INTRODUCTION

Due to the minimal bulk, ease of harvest, acceptable functional and aesthetic results, and low complication rates, skin grafts are commonly used in reconstruction of small to moderate-sized defects in the oral cavity [1]. Graft survival is largely dependent on two requirements: sufficient vascularity of the recipient bed and immobilization of the graft for subsequent adherence to the defect [2]. Stabilizing an intraoral skin graft poses unique challenges – an uneven wound bed, high mobility of the region, and accumulation of salivary secretions, which can all lead to skin graft failure [3]. To overcome these challenges, the skin graft is usually immobilized by means of a bolster. Multiple case reports have previously described techniques to immobilize the graft to the cheek using a bolster dressing for 5–7 days while the graft is most susceptible to shearing forces [3–5]. Less commonly than the cheek, intraoral skin grafts can be required in reconstruction of the floor of the mouth. In these occurrences, bolsters may be secured to the teeth or the alveolus. However, the difficulty arises in patients who have undergone an anterior marginal or composite mandibulectomy. To our knowledge, no reports have been presented in the literature on how best to bolster a skin graft to the floor of the mouth for adequate immobilization and adherence to the defect. In this report, we describe a bolstering technique that resulted in successful skin graft take to the floor of the mouth.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old man sustained a gunshot wound to the face resulting in significant bone and soft tissue loss. After multiple debridements, fixation of facial fractures, left-sided osteocutaneous free fibula flap for mandible reconstruction (defect spanning from angle to angle), and right-sided osteocutaneous free fibula flap for midface reconstruction, the patient desired dental restoration. To facilitate dental implants, the free fibula skin paddle used to reconstruct the floor of mouth was excised, the anterior sulcus recreated, and a U-shaped 7x4 cm split-thickness skin graft (STSG) was placed. This procedure was performed approximately 28 months following mandible reconstruction and 14 months following midface reconstruction. The STSG was harvested from the lateral aspect of the left thigh. The donor area was prepped with mineral oil and the STSG was harvested using a Zimmer® dermatome (Zimmer, Inc., Warsaw, IN) at a thickness of 0.4 millimeters. The STSG was then pie crusted by creating slits of approximately 5 mm in length, spread throughout the graft using a No.10 blade scalpel. The graft was trimmed to fit the defect, which covered the floor of the mouth and neo-gingivobuccal sulcus. The fenestrated graft was secured with a running 4-0 chromic suture along the defect perimeter and several interrupted sutures securing the graft to the wound base. The donor site was covered with OPSITE (Smith & Nephew, Hull, UK) dressing for three days. The OPSITE dressing was then exchanged with Xeroform (Kendall Brands of Covidien, Mansfield, MA) and left in place until it peeled off on its own.

TECHNIQUE

The graft was then immobilized to the floor of mouth using the bolstering technique described below:

- The bolster is created by mixing cotton balls with bacitracin and rolling them into four sheets of Xeroform (Kendall Brands of Covidien, Mansfield, MA).

- The bolster is then conformed to the shape of the skin graft that needs to be immobilized (Fig. 1A).

- The four poles of the bolster are secured using 2-0 silk tie-over sutures. The anterior suture is passed through the bolster, lower lip, and external Xeroform layer, then mattressed back through the Xeroform, lower lip, and bolster (Fig. 1B). The lateral sutures are passed through the inferior part of the cheek in a similar fashion. The posterior suture is passed through the frenulum. Care should be taken to avoid devascularizing the tissue with the bolster suture. In this case, both facial arteries were sacrificed for the free flap, and flow to the lower lip was retrograde. The cheek sutures were placed to avoid compromising flow to the lip.

- The ends of the 2-0 silk ties are knotted in the middle of the bolster (Fig. 2A, 2B).

- A safety suture can also be passed through the bolster and delivered out of the oral cavity and secured to the cheek with Steri-Strips (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN) or Tegaderm (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN). In the case of bolster dislodgement, the bolster can be pulled out by the extra-oral tie to avoid airway compromise.

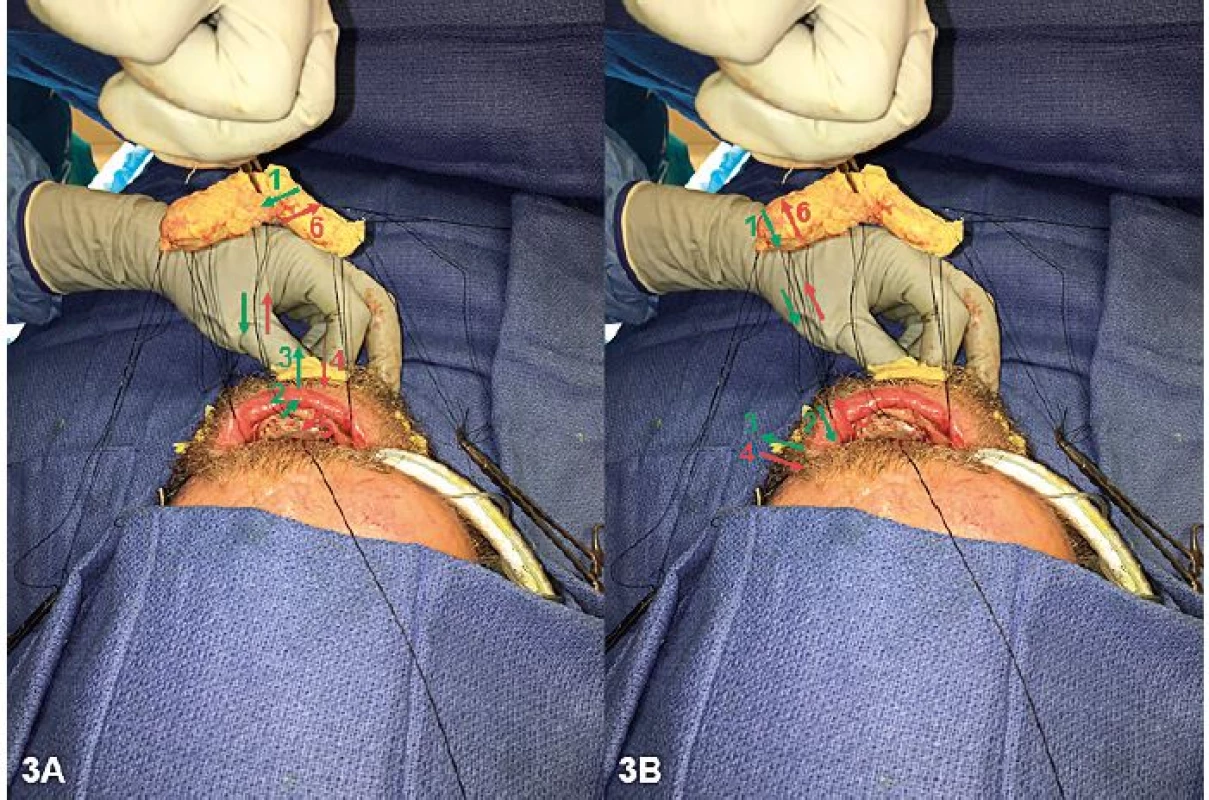

- The schematic view in Figure 3 illustrates how the sutures were placed in order to secure the bolster.

- The bolster was removed on day 5 following STSG placement.

1. (A, B) Application of the intraoral bolster. The bolster was secured using 2-0 silk-tie-over sutures at the anterior (A), posterior (P), and lateral (L1, L2) poles. A safety suture (S) was passed through the bolster

2. (A, B) Securing of the intraoral bolster. The bolster was placed over the graft, and the ends of the 2-0 silk ties were tied in the middle of the bolster. A safety suture (S) remained outside of the oral cavity for ease of removal in the case of bolster dislodgement and airway compromise

3. Scheme of the sequence of suture placement to secure the intraoral bolster. Schematic view of suture placement to secure the intraoral bolster. Green text/arrows depict the entry route of the sutures, and red text/arrows depict the exit route of the sutures. (A) The anterior sutures were run (1) through the Xeroform bolster, (2) through the graft in the anterior floor of the mouth, and (3) through the mentolabial sulcus (superior to the reconstructed osseous mandible) and an external piece of Xeroform. The suture was then run in the reverse direction: (4) through the external Xeroform and mentolabial sulcus, (5) through the graft in the anterior floor of the mouth, and (6) through the Xeroform bolster. (B) Similarly, the lateral sutures were run (1) through the Xeroform bolster, (2) through the graft in the lateral floor of the mouth, and (3) through the lateral cheek (superior to the reconstructed osseous mandible) and an external piece of Xeroform. The suture was then run in the reverse direction: (4) through the external Xeroform and lateral cheek, (5) through the graft in the lateral floor of the mouth, and (6) through the Xeroform bolster

DISCUSSION

Due to the inherent mobility of the region, bolsters are commonly required to stabilize intraoral skin grafts. Proper bolster placement requires application of constant and evenly distributed pressure in order to provide maximal contact between the graft and the recipient bed, reduction in shearing forces, and prevention of the accumulation of salivary secretions, hematoma, or seroma under the graft [6,7]. An ideal bolster should apply a force that exceeds interstitial pressure (15 to 20 mmHg) while not exceeding capillary perfusion pressure (25 to 30 mmHg) [8]; this balance is key to adequately immobilize the graft and close dead space while not limiting perfusion and risking graft breakdown. Although pressure was not quantitatively assessed in this patient, adequate bolster pressure can be determined based on the appearance of the sutures compressing the Xeroform bolster and the complete immobilization of the bolster over the floor of the mouth. Care should be taken to avoid excessive tension over the facial skin to prevent ulceration.

Bolster dressings aid in the distribution of pressure over a skin graft, and a number of techniques have been described to secure the bolster to the wound bed. These techniques include traditional tie-over [1,9], tie-over modifications [10–12], and externally secured [13,14] bolster methods. Despite the rich literature describing techniques for securing a bolster for skin graft adherence, to our knowledge a description of how best to secure a bolster to the floor of the mouth, especially after resection of the mandible, has never been described. In this article, the authors present a bolstering technique to secure a skin graft to the floor of the mouth when the alveolus and teeth are unavailable.

Alternative methods of skin graft fixation or surgical reconstructive options warrant mention. Other materials to construct a bolster could be considered, which should work equally as well as the Xeroform bolster described in this case report. Bolster materials most commonly described in the literature include foam, cotton, gauze, and silicone sheets. Any of these materials would likely be effective, as the innovative transoral bolstering suture technique rather than bolster material is largely responsible for the even distribution of pressure across the skin graft. Sealant options such as fibrin glue are likely unsuitable in the oral cavity due the high level of secretions and proximity to the gastrointestinal tract. For smaller defects, alternatives to a skin graft could be considered, such as buccal mucosa grafts or local flaps; however, given the extent (7x4 cm), unusual location (floor of mouth), and reconstructed anatomy (prior midface and mandible reconstructions) in this patient, these options were not available at the time of surgery.

CONCLUSION

This technique for securing a skin graft to the floor of the mouth was well-tolerated by the patient resulting in oral competence with no complications or visible scarring. A 100% skin graft take was obtained using this technique, which is simple and effective. No significant odor, patient discomfort, or change in care related to the oral cavity were noted in this case. While we did not experience spontaneous release of the bolster or suture failure, the inclusion of a safety suture allows for prompt bolster removal should unintended bolster dislodgement occur. Vascular supply of the facial soft tissues must be considered when placing transfacial sutures to secure a skin graft bolster.

In conclusion, we describe an innovative technique to secure a skin graft in the floor of the mouth – a challenging location, for which no bolstering technique is described. This technique provided even pressure distribution and secured the bolster to allow successful skin graft take with minimal patient discomfort and no complications. While transbuccal or transcutaneous approaches are typically adequate for securing a bolster in the oral cavity, the technique described in this case report is indicated in the rare cases where skin grafting to the floor of the mouth is required.

Conflict of Interest: The authors of this study certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Corresponding author:

Francesco M. Egro, MBChB MSc MRCS

Department of Plastic Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 3550 Terrace Street, 6B Scaife Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, United States

E-mail: francescoegro@gmail.com

Sources

1. Schramm VL Jr, Myers EN. Skin grafts in oral cavity reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980 Sep;106(9):528-32.

2. Zender CA, Petruzzelli GJ. Skin grafting in oral cavity reconstruction. Oper Tech Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2005 Mar.16(1):24-27.

3. Qureshi SS, Chaukar D, Dcruz AK. Simple technique of securing intraoral skin grafts. J Surg Oncol. 2005 Feb 1;89(2):102-3.

4. Friedlander AH, Miller J. Stabilization of intraoral skin grafts to the cheek. J Oral Surg. 1981 Jan;39(1):63.

5. Robiony M, Forte M, Toro C, Costa F, Politi M. Silicone sandwich technique for securing intraoral skin grafts to the cheek. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 Mar;45(2):166-7.

6. Wetton L, Kwei J, Kippen J, Nicklin S, Gillies M, Walsh WR. A model of pressure distribution under peripherally secured foam dressings on a convex surface: does this contribute to skin graft loss? Eplasty. 2010;10:e19.

7. Blair VP, Brown JB. The use and uses of large split skin grafts of intermediate thickness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968 Jul;42(1):65-75.

8. Weiner LJ, Moberg AW. An ideal stent for reliable and efficient skin graft application. Ann Plast Surg. 1984 Jul;13(1):24-8.

9. Wolf Y, Kalish E, Badani E, Friedman N, Hauben DJ. Rubber foam and staples: do they secure skin grafts? A model analysis and proposal of pressure enhancement techniques. Ann Plast Surg. 1998 Feb;40(2):149-55.

10. Pelissier P, Martin D, Baudet J. The running tie-over dressing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 Nov;106(6):1436-7.

11. Joyce CW, Joyce KM, Mahon N, et al. A novel barbed suture tie-over dressing for skin grafts: a comparison with traditional techniques. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014 Sep;67(9):1237-41.

12. Westerband A, Fratianne RB. Stapled tie-over stent: a simplified technique for pressure dressings on newly applied split-thickness skin grafts. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1993 Jul-Aug;14(4):463-5.

13. Chaturvedi P, Pai PS, Decruz AK, et al. Extra-oral knotting of tie-over sutures: a novel technique to bolster the split thickness skin graft for a buccal mucosal defect. J Surg Oncol. 2003 Oct;84(2):103-4.

14. Garvey CM, Panje WR, Hoffman HT. The’parachute’ bolster technique for securing intraoral skin grafts. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001 Oct;80(10):720, 723.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine Traumatology

Article was published inActa chirurgiae plasticae

2018 Issue 1-

All articles in this issue

- Pedicled pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction - technique and overview

- Securing intraoral skin grafts to the floor of the mouth: case report and technique desription

- Intraosseous haemangioma od the zygoma - case report and literature review

- Editorial

- Pedicled pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction - our experience

- In memoriam: Professor Rajko Doleček

- Commemoration of professor Miroslav Fára, M.D., DSc.

- Use of licap and ltap flaps for breast reconstruction

- Image Possibilities of the Peripheral Nerve Tumor Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging - Case Report

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Pedicled pectoralis major flap in head and neck reconstruction - technique and overview

- Use of licap and ltap flaps for breast reconstruction

- Editorial

- Intraosseous haemangioma od the zygoma - case report and literature review

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career