-

Medical journals

- Career

Osteosynthesis of dislocated calcaneal fractures at our centre using the intramedullary C-Nail

Authors: Jan Vrchovecký

Authors‘ workplace: Chirurgie a úrazová chirurgie, Městská nemocnice Ostrava

Published in: Úraz chir. 25., 2017, č.3

Overview

Introduction:

The presented article deals with the possibilities of treatment of calcaneal fractures. Lately, angularly stable plates applied from the lateral approach, so called Seattle incision, have been used at most clinical departments; however, this technique is associated with a greater percentage of local infectious and ischaemic complications.

Aim:

The aim of the article is to evaluate osteosyntheses of the calcaneus using the relatively new technique of intramedullary nailing using the C-NAIL.

Material and methods:

The author builds upon his own patient population, in whom a total of 31 osteosyntheses of the calcaneus were performed between 7/2014 and 12/2016; thirty of these cases were treated with the C-NAIL, in one case of open fracture, transfixation with K-wires was performed.

Results:

No serious complications which would require an arthrodesis have been observed during the 2-year follow-up; nevertheless, this time frame is too short to reliably evaluate this aspect. In a direct comparison, the results in patients after osteosyntheses using the nail are associated with significantly better results when compared to patients treated with angularly stable plate, considering the functional outcome and complications associated with wound healing.

Conclusion:

Based upon the results obtained among the observed patient population, osteosynthesis of the calcaneus using the C-NAIL provides better results when compared to the use of angularly stable plate. Considering the procedure in itself, and the mini-invasive approach when treating these fractures, a better healing of soft tissues is observed, with a minimum of ischaemic and infectious complications when compared with LCP plate applied using the ORIF technique.

Keywords:

Calcaneus, C-NAIL, intramedullary osteosynthesis of the calcaneus, LCP plate.

INTRODUCTION

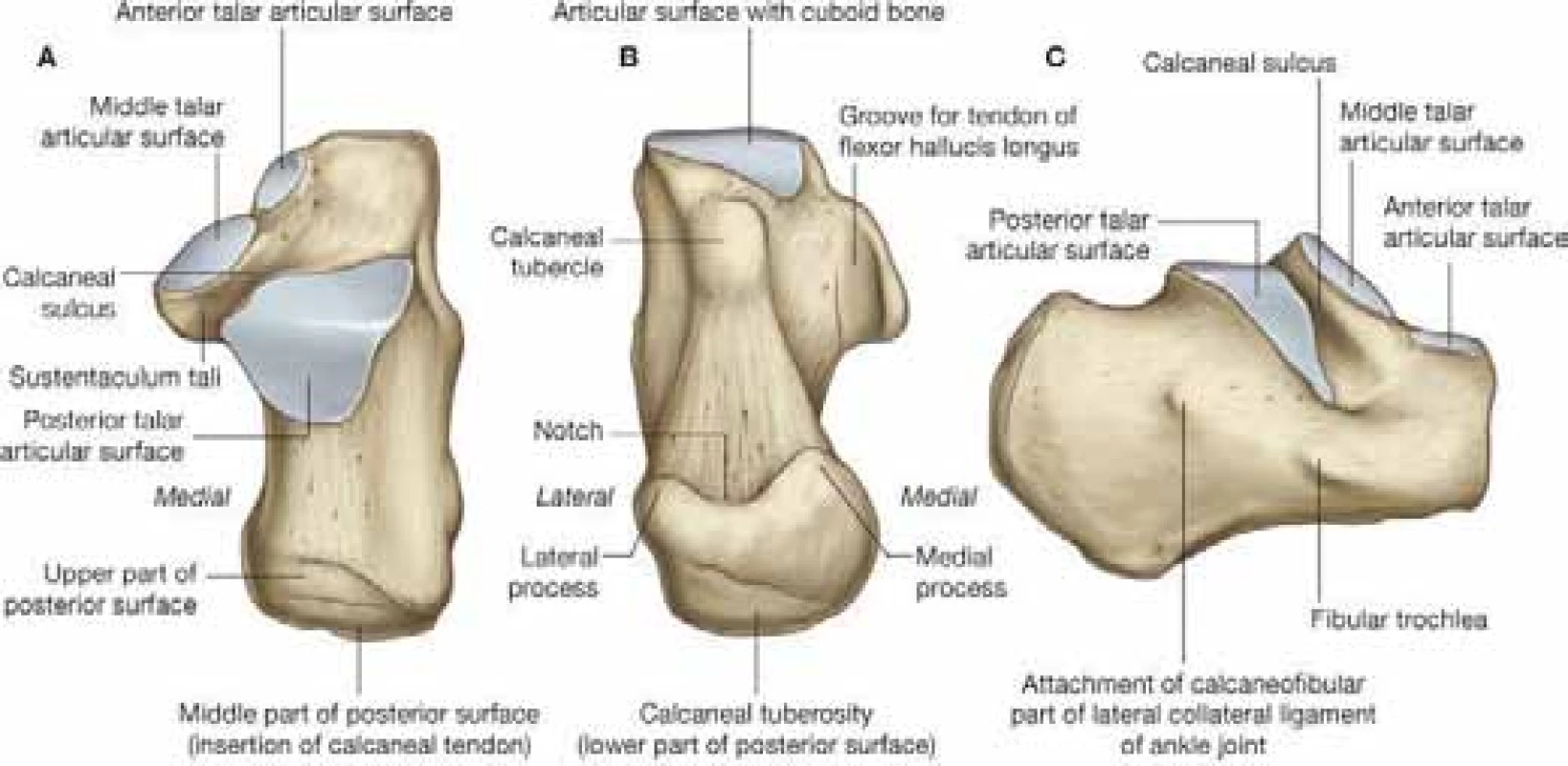

Anatomy of the calcaneus

The calcaneus is the largest of the seven tarsal bones. There are four articular surfaces – anterior, medial, and posterior articular surfaces form the talocalcaneal joint. The calcaneocuboid joint is located ventrally.

The posterior articular surface is of oval and convex shape, with laterocaudal angle of 45°. It forms an independent joint and supports the talus. This anatomical structure is a key in the pathological mechanism of intraarticular fractures. Ventrolaterally, it leads to sinus tarsi.

The medial articular surface is oval and concave, and is located above the sustentaculum. It is anatomically variable. Sulcus calcanei is located between the medial and posterior facet, which forms the bottom of the tarsal canal.

The anterior articular surface is located anterolaterally from the medial facet, it ventrally borders with the sinus tarsi; ligamentum bifurcatum is attached to it, which consists of two parts – ligamentum calcaneonaviculare and ligamentum calcaneocuboideum. The tarsal canal further forms five ligaments – 3 parts of the lower extensor retinaculum, and the talocalcaneal interosseous ligament, which consists of two parts – oblique talocalcaneal (cervical) ligament, and the ligament of the tarsal canal [4, 10].

The anterior surface of the calcaneus is covered with an articular surface, which is a part of the calcaneocuboid joint, and is transversely convex, connected to the cuboideum with a plantar calcaneocuboid ligament. The ventrolateral part of the calcaneus, with the anterior and medial facet, help support the lateral process of the talus. The subtalar joint is strengthened with three ligaments located outside of the joint capsule, ligamentum talocalcaneum interosseum, laterale and mediale. The third joint, upon which the calcaneus participates, is the talocalcaneonavicular joint, also called “coxa pedis”, due to its spherical shape. Ligamentum calcaneonaviculare stretches from the sustentaculum to the tuberosity of the navicular bone, which transfers into a fibrous cartilage enlarging the fossa articularis. It has two parts, and as the so-called “spring ligament” participates upon the formation of the arch of the foot by supporting the talus head. In case of its rupture, the longitudinal and transverse arches of the foot become flat due to insertion of the talus in between the calcaneus and the navicular bone [3, 4]. The largest ligament of the calcaneus is the Achilles tendon, which is attached to the calcaneal tuber.

1. Anatomy of the calcaneus. (Adapted from Gray’s anatomy for students, 2nd Edition, Copyright 2009©Churchill Livingstone, ISBN 9781437720556)

History of treatment of calcaneal fractures

Calcaneal fractures represent only a minor part of the overall number of fractures, approx. 1-2%. Dislocated intraarticular calcaneal fractures represent approx. 70% of all calcaneal fractures in adults [12, 16]. The associated mechanism of injury usually includes landing onto extended lower extremities when jumping from heights. The impact of these fractures, although relatively small when considering the whole human body size, is very serious due to its often-disabling consequences for the patient. Also the economic impact of treating these fractures is relatively high, that is why great attention is given to the problems of treatment and management of consequences of these fractures.

Over time, medicine has diverted from purely conservative therapy. At first, reduction manoeuvres were used, greatly aided by introduction of X-ray into practice; subsequently, there were attempts to perform a surgical reduction using Kirschner extension and a redression apparatus, later on using e.g. the technique of Steinmann nail insertion into tuber clacanei [2]. In the following years, various attempts have appeared to perform a bloody reduction of the posterior articular surface with elevation using a raspatory from a small lateral approach, with insertion of a bone graft, as published for example by Palmer [7].

Although the first reports about calcaneal bone osteosynthesis date back to the beginning of the 20th century, the surgical therapy with open reduction and stable internal fixation has seen greater development since the 1980s, due to the development and subsequent routine use of computed tomography, which made the diagnostics and classification of calcaneal fractures more precise. The most frequently used classification was presented in 1990s by Sanders and is based upon CT examinations, which formed the basis of a relatively precise and currently still used system of indications for surgical therapy [13].

Current state

During the recent years, the treatment of first choice of intraarticular calcaneal fractures at most centres remains the angularly stable plate, developed by the Synthes Company, in cooperation with the AO Foundation, which is applied from the lateral approach, using the Seattle incision. This type of surgery is associated with great demands for good condition of the soft tissues; according to the literature, the risk of postoperative marginal necroses varies between 0.4 and 14 % [5,9]. This differentiation depends on the perfectly performed incision, and the need for knowledge of the anatomy of vascular supply of the lateral surface of the foot.

In case of open fractures, it is beneficial to use an open fixation or perform a transfixion using K-wires, in order to bridge over the healing period of soft tissues. Subsequent conversion to another type of osteosynthesis is possible, however, it is not frequently applied.

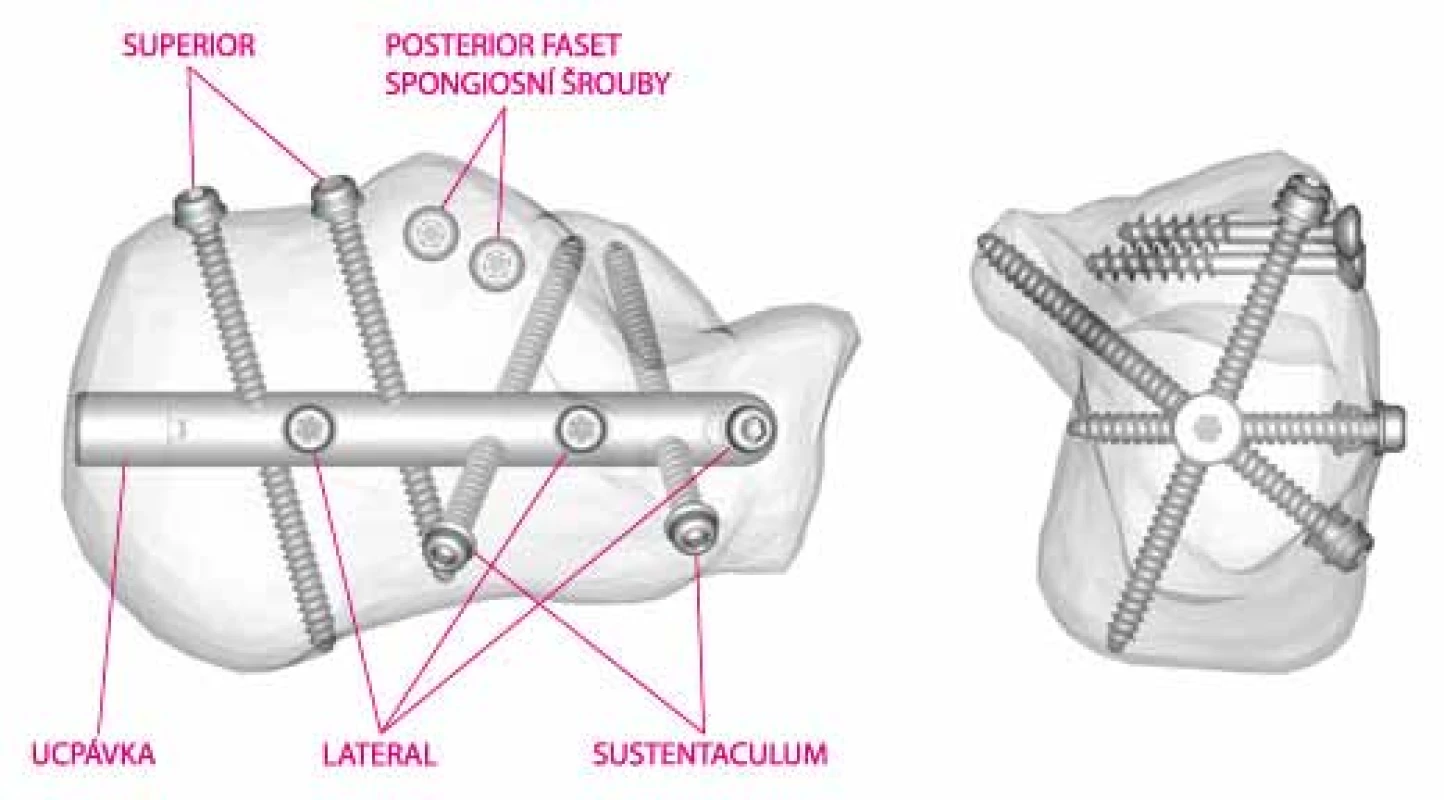

Since 2012, there exists another possibility in the treatment of undislocated intraarticular calcaneal fractures using a calcaneal nail. This nail has been developed by the Medin Company, in cooperation with the Pardubice Regional Hospital and the University Clinic in Dresden. The nail may be used both for treatment of extraarticular and intraarticular fractures of the Sanders I-IV type, Joint Depression type I Tongue type, according to the Essex-Lopresti classification.

2. Assembled targeting device with the C-Nail

3. Scheme of nail placement (Surgical technique C-Nail – www.c-nail.eu)

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patient file

At our centre, this surgical technique has been used as a treatment of choice since 2014. In the period from 7/2014 to 12/2016, we performed an osteosynthesis of 31 calcaneal fractures; we used the C-NAIL in 30 of them.

Division according to Sanders classification:

Sanders IISanders IIISanders IVNo. of patients9156%305020In one case of open fracture Sanders type IV, we performed a fixation using K-wires. We usually performed the surgery as a delayed procedure, due to the swelling of soft tissues, in the range of 1-22 days from the injury, and the average delay of 8.3 days from the initial trauma. In case of a bilateral calcaneal fracture, we did not perform an osteosynthesis of both bones, the fixation was always unilateral.

Surgical procedure

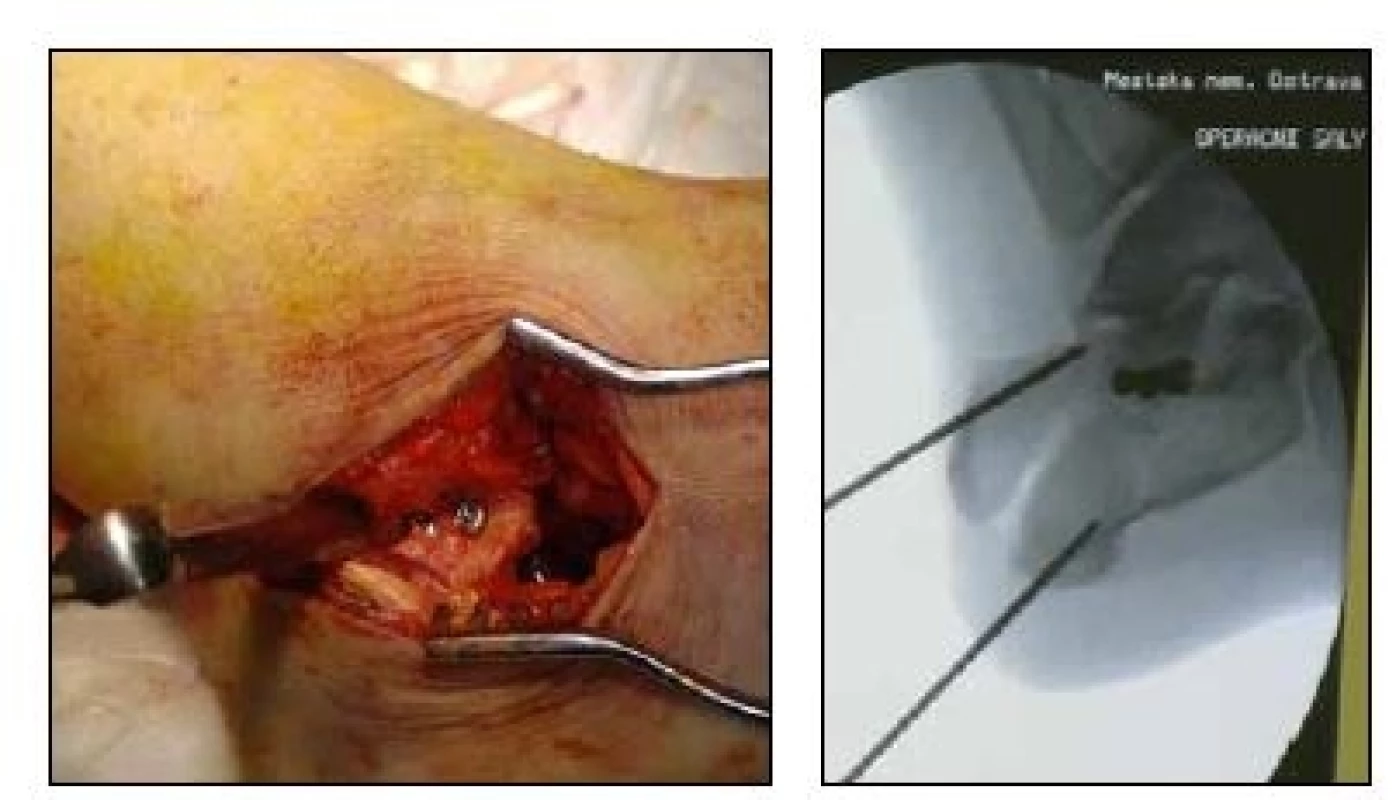

We usually operate our patient under antibiotic coverage, with preoperative administration of Cefazolin, with the patient placed on the healthy side, with slightly bent extremity and applied tourniquet. The bloodless period lasted 52 minutes on average, varying from 30 to 75 minutes. The surgical procedure begins with approx. 4-centimeter lateral incision from the apex of the fibula towards the basis of the 5th metatarsus; we continue via sinus tarsi to the posterior articular surface, where we perform an open reduction, sometimes also using a Schantz screw inserted to tuber calcanei in the area of the presumed nail course; after restoration of the Böhler angle, we perform a fixation using usually two spongious screws with a short thread below the articular surface (Fig. 4).

4. nsertion of spongious screws fixing the posterior articular surface

The position of the screws is verified with radiographs in standard and the Broden’s projections. Subsequently, we perform a small incision at the site of nail insertion, under the attachment of the Achilles ligament, and insert a guidewire towards the middle of the calcaneocuboid joint. The positioning of the wire is verified by X-ray, in two projections. Drilling of the opening for the nail is performed using a cannulated drill bit along the guidewire, the soft tissues are protected by the drill bit casing, the depth of drilling is controlled in the lateral projection, and reaches approx. 5 cm below the calcaneocuboidal joint. Then, the nail is inserted into the opening, with subsequent insertion of guidewires with a knob into the sustentaculum process through a guiding device marked as SUSTENTACULUM, and a yellow-coloured case. After verification of the correct position, an opening is drilled for the screw; the length is measured with a calibrated drill bit. The remaining screws are inserted through guiding devices marked as SUPERIOR and LATERAL in the same way [6].

During the surgical procedures performed at our centre, we used all locking screws in 20 cases (66.6%), and fewer screws in the remaining cases (Fig. 5).

Suture of the surgical wounds is performed with nonresorbable material, no drainage is used.

5. Final radiograph after osteosynthesis

Postoperative procedure

After surgery, bandages are applied onto the foot, with ice pads and elevation, no plaster fixation is used. On the first postoperative day, the patient begins with physiotherapy, without any loading of the operated extremity; after the patient has managed to walk on crutches, we discharge the patient into home care. The patients are usually discharged on the 3rd or 4th postoperative day, unless the healing of soft tissues is significantly impaired.

Stitches are removed depending on the process of healing, usually on the 10th-14th postoperative day, followed with, usually outpatient, physiotherapy at our Department of Clinical Rehabilitation.

We allow the patient to load the extremity to 30% after 5-6 weeks, based upon a control radiograph, full load bearing is possible after 12 weeks.

RESULTS

No significant complication has been observed among the patients operated at our centre for the period of two years, which would require an arthrodesis; nevertheless, this time frame seems to be too short in order to reliably evaluate this aspect. In direct comparison, the results in patients with osteosynthesis using a nail performed at our centre are significantly better than the results in patients treated with osteosynthesis using an angularly stable plate, which has not been used at our centre since the introduction of nail osteosynthesis. The average value of the Böhler angle was 7.5° preoperatively, and 22.5° during postoperative X-ray assessment. The postoperative complications depended, based upon a subjective assessment of the patients, not only upon restoration of the Böhler angle but also on the correct reduction and restoration of the calcaneal length, and reduction of the valgus and varus deformities.

Available world literature claims that in case the osteosynthesis is performed, due to swelling and impairment of soft tissues, after 14 and more days from the injury, the possibility of anatomical reduction is significantly impaired due to fibrous healing and scarring of soft tissues, and the risk of infection and secondary wound healing increases. [1, 11, 14, 15]. We did not observe any infectious complication among our patients. Marginal necrosis of the wound was observed in one patient (3.5%), a strong smoker, who consumed 40-60 cigarettes a day.

Among our patients, the surgical procedure was performed after 22 days in one case, due to enormous swelling and impairment of soft tissues, and we may confirm the above-stated theory. Performing an exact reduction was almost impossible after this period due to fibrous healing of the bone, it was necessary to disintegrate these bridges, and restoration of the bone contour resulted in a significant destruction of the spongious and also cortical part of the bone. Despite the performed spongioplasty, the result of this osteosynthesis remains very unsatisfactory. Even during radiographic control performed after nine months, we observed a Böhler angle of 0°, varus deformity of 15°, and shortening of the calcaneus. Nine months after trauma, the female patient is mobile, however experiences pains even when walking a short distance. Unless the condition of the patient improves in the following year, we are planning to manage this situation with a subtalar arthrodesis.

DISCUSSION

Calcaneal osteosynthesis remains a controversial topic; despite the availability of modern mini-invasive implants, many trauma surgeons prefer a conservative approach even today, due to fear of soft-tissue healing and the functional outcome. In case of the calcaneus, the old rule that an anatomically perfect radiograph does not grant a good functional outcome especially applies. In cases when a surgical management is indicated, it is important to select a suitable implant, which will ensure the best preconditions for subsequent convalescence and physiotherapy of the patient. An important condition when treating patients with calcaneal fractures is that the medical centre has all common possibilities, and an experienced trauma surgeon available, who knows these not completely routine procedures well.

CONCLUSION

Based upon the results obtained among the observed patient population, osteosynthesis of the calcaneus using the C-NAIL provides better results when compared to the use of angularly stable plate. Considering the procedure in itself, and the mini-invasive approach when treating these fractures, better healing of soft tissues is observed, with a minimum of ischaemic and infectious complications when compared with LCP plate applied using the ORIF technique. Postoperatively, it is not necessary to immobilize the extremity using a plaster fixation, we apply bandages only, and the patient may begin with early physiotherapy; this procedure also decreases the risk of thromboembolic disease [8].

According to subjective assessment of the patients, and also our observations, a good functional outcome in the postoperative period does not depend on an appropriate restoration of the Böhler angle only. Identically significant is also restoring the length of the calcaneus and reduction of valgus and varus deformities.

Sources

1. BENIRSCHKE, SK., KRAMER, PA. Wound Healing Complications in Closed and Open Calcaneal Fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004, 18, 1–6.

2. GISSANE, W. A discussion on „fractures of the os calcis“. J Bone Jt Surg. 1947, 29, 254–255.

3. GROSS, JM., FETTO, J., ROSEN, E. Vyšetřeni pohyboveho aparatu. Praha : Triton, 2005. Translation. Copyright 2002 by Gross, JM, Fetto, J, Rosen E. 599 s., ISBN80-7254-720-8

4. KEENER, BJ., SIZENSKY, JA. The Anatomy of the Calcaneus and Surrounding Structures. Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2005, 10, 413–424.

5. KOSKI, A., KUOKKANEN, H. Postoperative wound complications after internal fixation of closed calcaneal fractures a retrospective analysis of 126 consecutive patients with 148 fractures Scand J Surg. 2005, 94, 243–245.

6. Operační postup C-NAIL Medin – www.c-nail.eu

7. PALMER, J. The mechanismus and Treatment of Treatment of the Calcaneus. J Bone Jt Surg. 1948, 30A, 1–8.

8. POMPACH, M., CARDA, M., ŽILKA, L. et al. Hřebování patní kosti C-NAIL. Úraz chir. 2015, 23, 2. ISSN 1211-7080

9. POPELKA, V., ŠIMKO P. Operačná liečba intraartikulárnych zlomenín pätovej kosti. Acta Chirurg Orthopaedic et Traumatol Čech. 2011, 78, 106–113.

10. RAK, V., IRA, D., MAŠEK, M. Operative treatment of intra-articular calcaneal fractures with calcaneal plates and its complications. Indian J Orthop. 2009, 43, 271–280.

11. RAMMELT, S., BARTHEL, S., BIEWENER, A. et al. Calcaneusfrakturen-offene Reposition und interne Stabilisierung. Zentralbl Chir. 2003, 128, 517–528.

11. RAMMELT, S., ZWIPP, H. Fractures of the Calcaneus: Current Treatment Strategies. Acta Chirurg Orthopaedic et Traumatol Čech. 2014, 81, 177–196.

12. SANDERS, R. Displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000, 82, 225–250.

13. SANDERS, R. Intra-Articular Fractures of the Calcaneus: Present State of the Art. J. of Orthop. Trauma. 1992, 6, 252–265.

14. STEHLÍK, J., ŠTULÍK, J. Zlomeniny patní kosti. Praha : Galén, 2005. 114 s. ISBN8072623281

15. TENNENT, T., CALDER, P., SALISBURY, R. et al. The operative management of displaced intraarticular fractures of the calcaneum: a two-centre study using a defined protocol. Injury. 2001, 32, 491–496.

16. ZWIPP, H, RAMMELT, S, BARTHEL, S. Fracture of the calcaneus. Unfallchirurg. 2005,108, 737–748.

Labels

Surgery Traumatology Trauma surgery

Article was published inTrauma Surgery

2017 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Therapeutic algorithm in a patient with open tibial fracture with extensive laceration of the soft tissue coverage – case report contribution to the discussion about limb salvage

- Bifocal bone transport in the treatment of infected nonunion of the tibia - case report

- Osteosynthesis of dislocated calcaneal fractures at our centre using the intramedullary C-Nail

- The Treatment of Comminutive Intraarticular Calcaneal Fractures by External Fixation

- Trauma Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- The Treatment of Comminutive Intraarticular Calcaneal Fractures by External Fixation

- Therapeutic algorithm in a patient with open tibial fracture with extensive laceration of the soft tissue coverage – case report contribution to the discussion about limb salvage

- Osteosynthesis of dislocated calcaneal fractures at our centre using the intramedullary C-Nail

- Bifocal bone transport in the treatment of infected nonunion of the tibia - case report

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career