-

Medical journals

- Career

Extensive bile duct injury resulting from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy resolved by a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy: a case report

Authors: A. Drs 1; M. Kocík 1; J. Chlupac 1,2; J. Froněk 1,2,3

Authors‘ workplace: Transplant Surgery Department, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague 1; Department of Anatomy, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague 2; 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague 3

Published in: Rozhl. Chir., 2020, roč. 99, č. 9, s. 403-407.

Category: Case Report

doi: https://doi.org/10.33699/PIS.2020.99.9.404–408Overview

Introduction: Bile duct injuries (BDIs) that occur after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) are among the most serious iatrogenic injuries and have high morbidity and mortality. They significantly impact the quality of life of the patient. They are one of the most common causes of benign biliary strictures, which can result in serious complications such as recurrent cholangitis or secondary biliary cirrhosis. Although LC is a common operation today, the incidence of BDIs associated with LC is twice that of BDIs resulting from open cholecystectomies.

Case report: In this paper, we present a case report of a patient after LC with the Class III-D injury according to the Stewart-Way classification. The injury was a result of a misleading description from a preoperative ultrasonography and a subsequent misunderstanding of the anatomical conditions of a patient with congenital gallbladder agenesis. The BDI was recognised first day after surgery. Thanks to a prompt transfer to our centre the patient was in a good condition. Biliary reconstruction could be done because there was no serious inflammation or biliary peritonitis at the time of reoperation. Due to the extent of the injury a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy combined with external transhepatic biliary drains was performed.

Conclusion: Iatrogenic BDI after a LC is a rare, but potentially life-threatening complication. The main risk factor is the presence of anatomical variants of the biliary tract. Early recognition and treatment in a department with adequately experienced hepatobiliary specialists are crucial for a positive outcome. The most frequent surgical treatment is a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy.

Keywords:

laparoscopic cholecystectomy – gallbladder agenesis – bile duct injury – surgical repair

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is a basic medical treatment of symptomatic gallstone disease. It is one of the most common operations in abdominal surgery. Bile duct injuries (BDIs) are among the most serious iatrogenic injuries. They have high morbidity and mortality and tend to significantly impact the quality of life of the patient. BDIs are one of the most common causes of benign biliary strictures [1], which can result in life-altering complications such as recurrent cholangitis or secondary biliary cirrhosis. Despite increasing experience and progress in laparoscopic skills, the incidence of BDIs associated with LC is twice that of BDIs resulting from open cholecystectomies [2−5].

We present this case report to recall the risk of injury during a common LC. The preoperative abdominal ultrasonography was misleading and the absence of the gallbladder, also known as gallbladder agenesis, was not known before the surgery. The effort to find the gallbladder and complete the LC unfortunately led to an extensive BDI.

Case report

A 45year-old male underwent LC in another hospital due to symptomatic gallstone disease. He had no prior history of cholecystitis, biliary pancreatitis or jaundice. He complained of occasional abdominal pain in the epigastrium, atypically localized in the left upper quadrant, and flatulence. The abdominal ultrasonography revealed a shrunken gallbladder with a 23mm stone.

As described in the operative report, the gallbladder was found in an atypical position leaning to the left liver lobe with an aberrant hepatic duct. The gallbladder was very small, almost undeveloped. Despite the not quite clear actual anatomy the operation was completed laparoscopically with ligation of the aberrant hepatic duct using clips. The size of the dissected organ was 25×18×6mm and no lithiasis was found. The first day after surgery the patient was in a good condition; however, laboratory results showed elevated obstructive enzymes (ALT 13.1 μkat/l; AST 9.8 μkat/l; Bili 84,0 μmol/l; GMT 10.0 μkat/l; ALP 2.3 μkat/l). Hence, he was referred to our hospital with a suspected BDI. A video record of the operation was sent, as well.

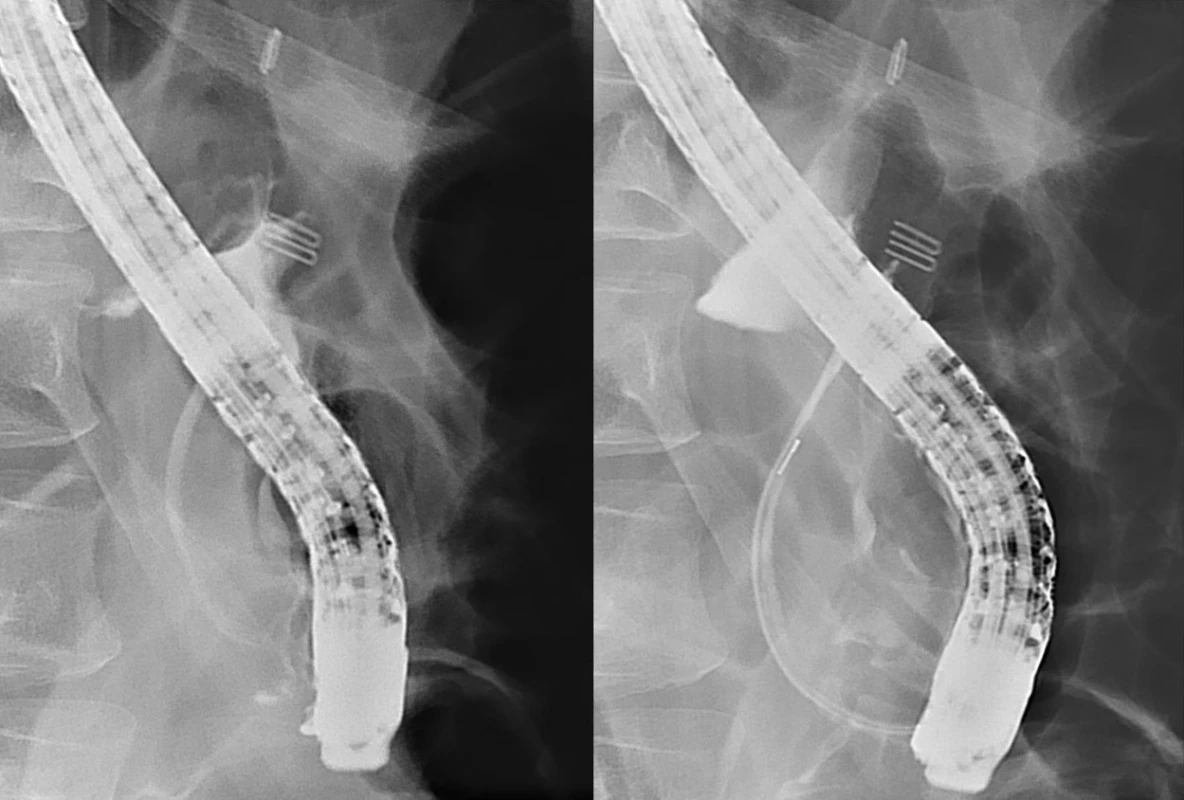

After admission, we arranged a magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP), but due to the patient’s anxiety it was cancelled. Computed tomography (CT) angiography confirmed the absence of any vascular injury (Fig. 1), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed a partial cut-off of the contrast medium, 7 cm above the ampulla of Vater, with a simultaneous massive leak (Fig. 2).

1. CT angiography confirming the absence of vascular injury

2. Partial cut-off of the contrast medium, 7 cm above the ampulla of Vater, with a simultaneous massive leak on the ERCP

The patient was operated on the same day. We found an artery branch leading to the posterolateral liver sector that was cut and clipped. Unfortunately, it was unreconstructable. The common bile duct was double clipped above the pancreatic edge. There were three clipped ducts in the liver hilum: the right and left hepatic duct and the hepatic duct for segment IV of the liver. All of the structures were roughly 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter. According to Stewart-Way classification, this was a Class III-D injury. In order to perform biliary reconstruction, all the ends of the clipped ducts, which were already necrotic, had to be shortened to the healthy tissue. We considered performing a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy combined with two external transhepatic biliary drains, inserting the first into the left hepatic duct and the other into the right hepatic duct.

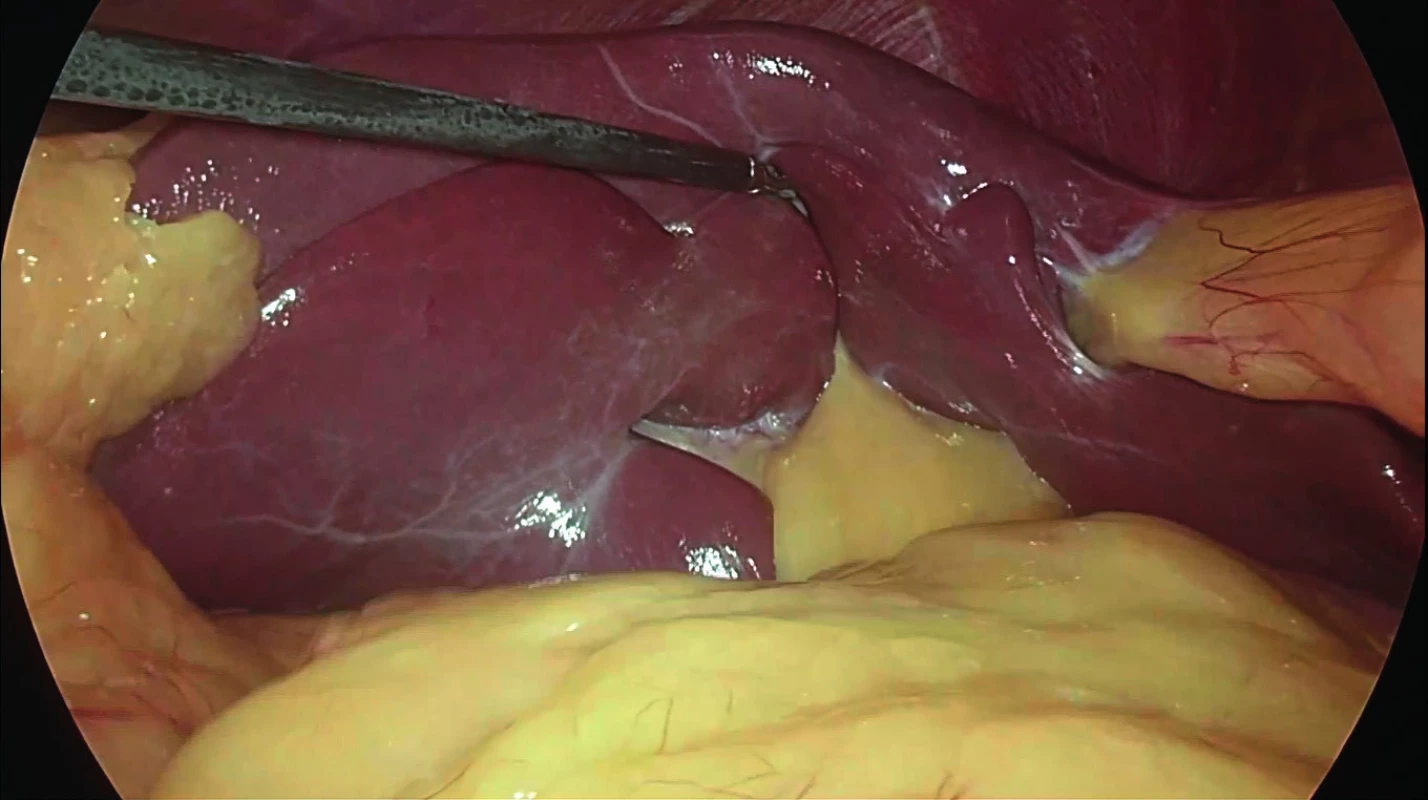

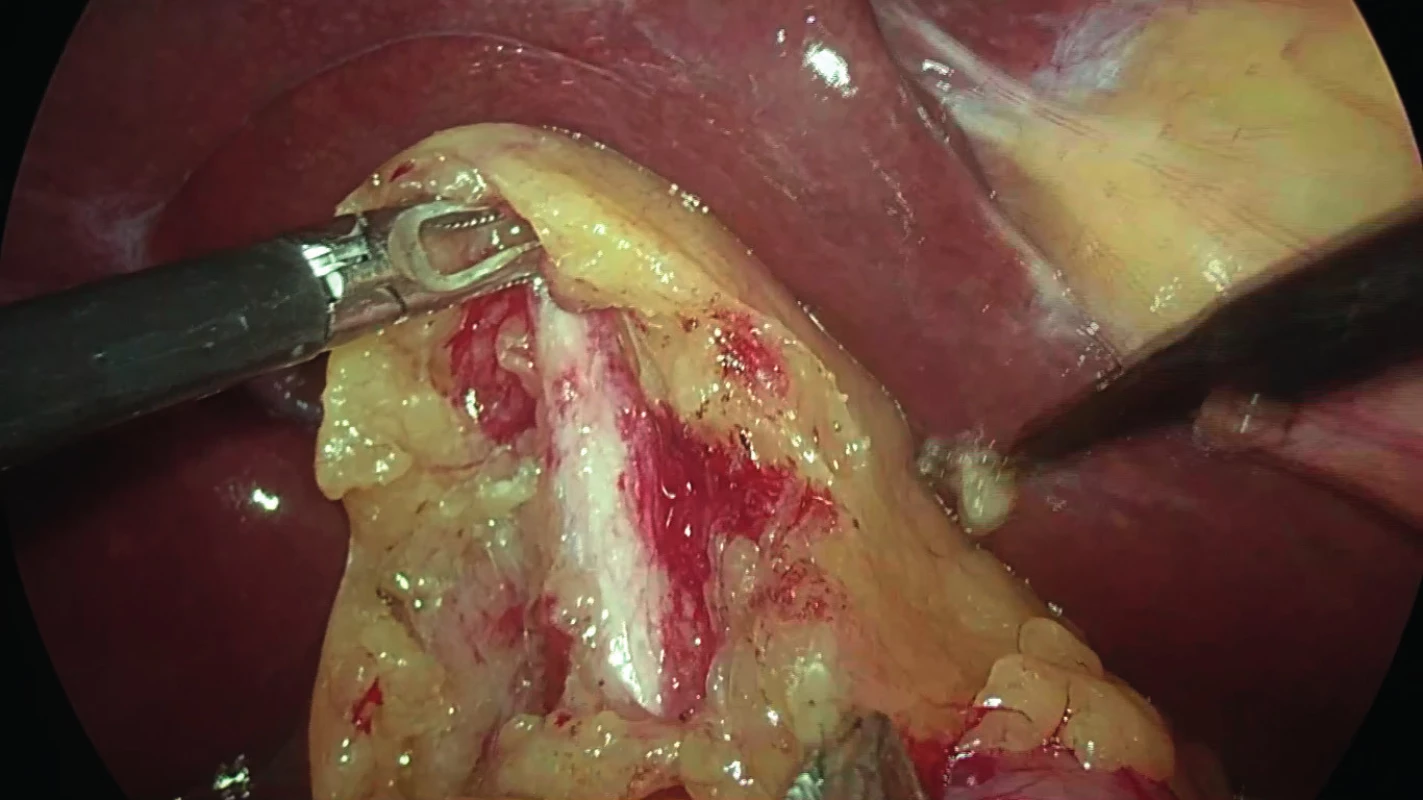

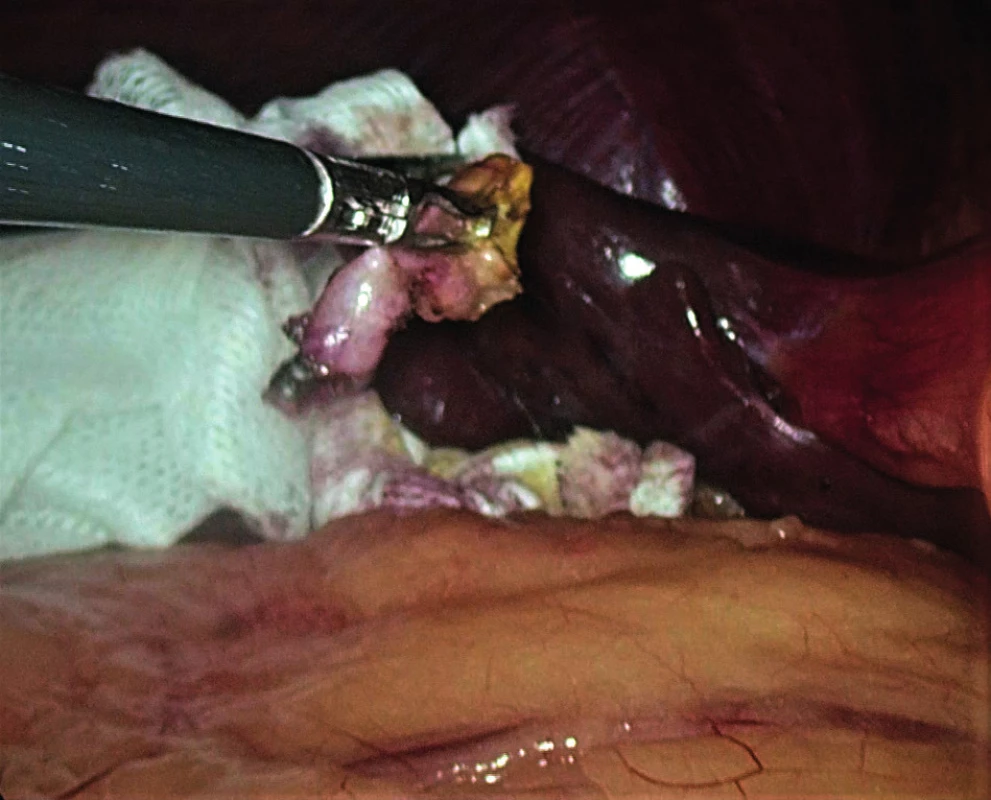

The video record of the LC was very beneficial for us because only after observing it we completely understood what happened during the LC: that the structure, which had been believed to be the shrunken gallbladder, was in fact the common hepatic duct (CHD) and that the patient had a very rare anatomic anomaly known as gallbladder agenesis (Figs. 3, 4). A complete excision of the CHD was carried out in lieu of cholecystectomy (Fig. 5).

3. View on the liver hilum at the beginning of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy

4. Dissected common hepatic duct (CHD) mistaken for a shrunken gallbladder

5. Extirpated organ at the end of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Two days after the biliary reconstruction a biliary leak appeared in the abdominal drain. Based on contrast radiography confirming a biliary leak from the right external biliary drain, we carried out a revision with repositioning of the biliary drain and suturing of the small dehiscence of the hepaticojejunoanastomosis of the left hepatic duct, which we revealed during the operation. The external biliary drains were irrigated daily in order to secure their function. Subsequent postoperative course was uneventful. Liver tests became normalized prior to the patient being discharged. The patient was sent home 33 days after biliary reconstruction in a very good condition with his surgical wound completely healed. Final histology of the dissected organ described no malignancy, only chronic hypertrophic and atrophic inflammation. The current follow-up is 6 months after the reconstructive surgery and the patient still remains in a good general condition. The patient will be kept under long-term surveillance because of the risk of long-term biliary complications, especially strictures.

Discussion

The incidence of BDIs after LC is approximately 0.4% [2−4]. The most frequent cause is an incorrect interpretation of biliary anatomy. The frequency of injury is higher during a laparoscopic procedure than during an open cholecystectomy, where the incidence is approximately 0.2% [5]. Early recognition of a BDI is one of the most important factors affecting the long-term implications of the injury, along with subsequent treatment in a department with adequately experienced hepatobiliary specialists.

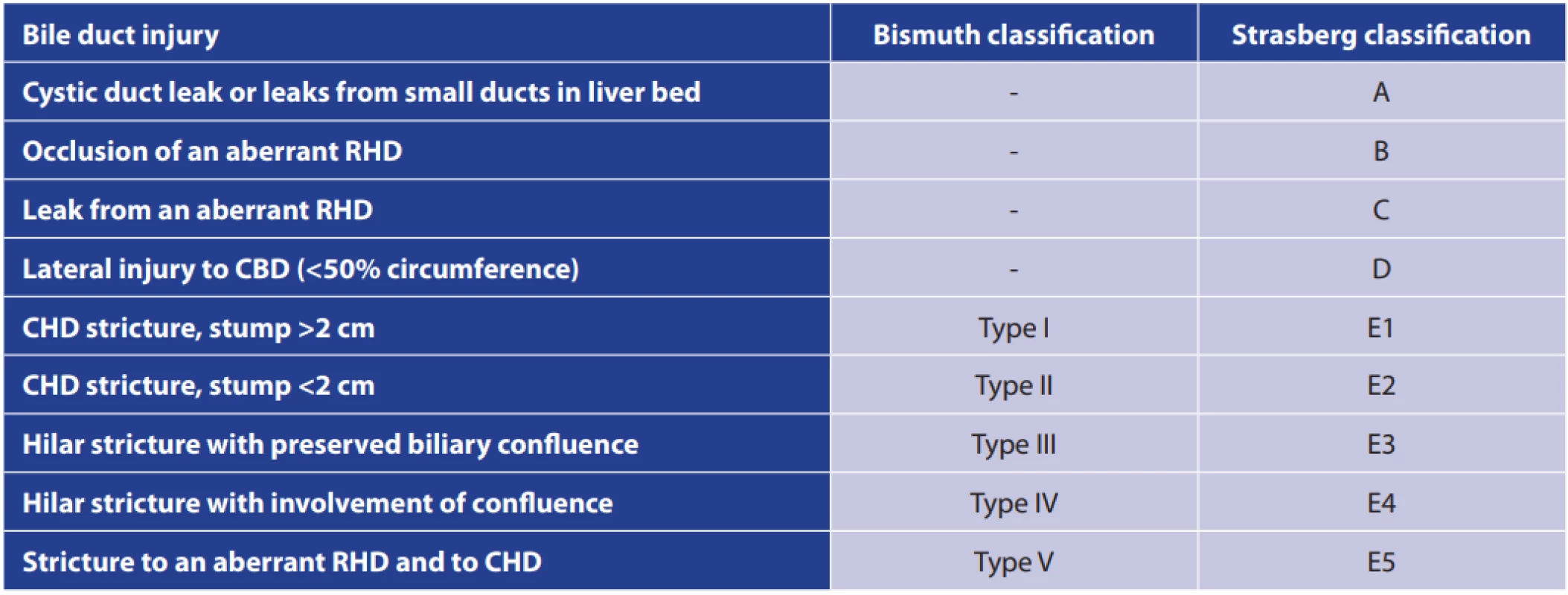

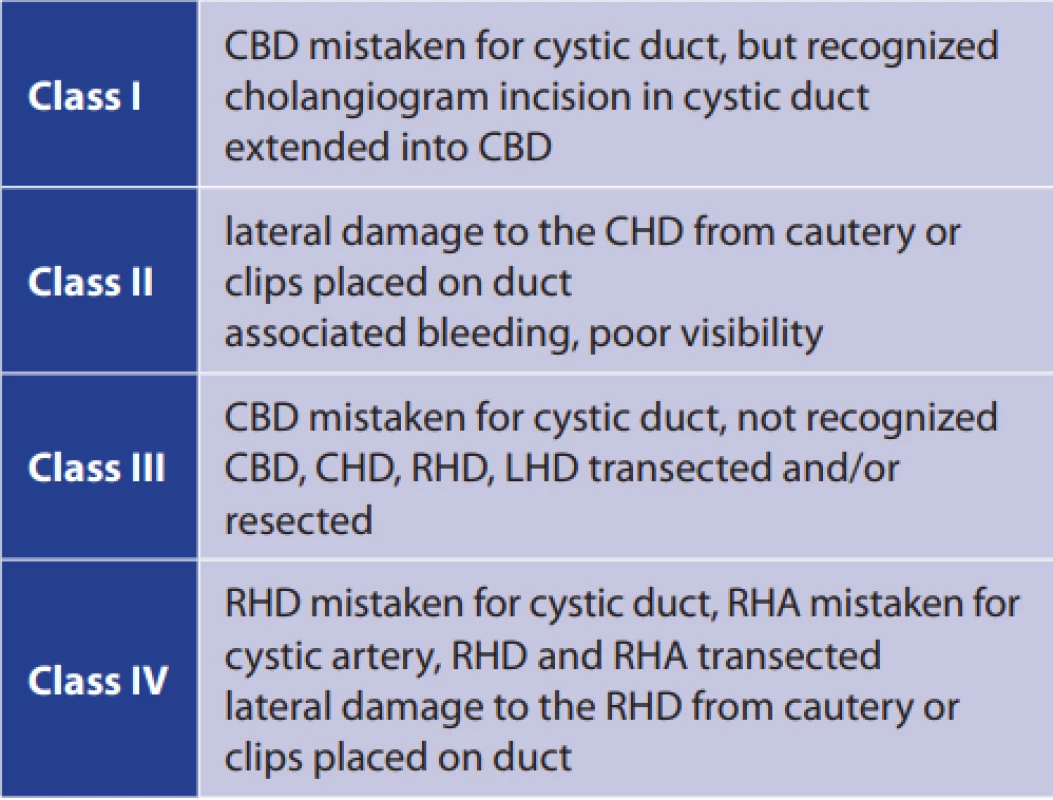

There are many types of BDI classification. The older ones are known as the Bismuth [6] and Strasberg [7] classifications (Tab. 1). The Stewart-Way classification of laparoscopic BDIs includes four classes of injury based on the mechanism and anatomy of the BDI (Tab. 2). This classification was created on the basis of the analysis of 252 laparoscopic BDIs [8]. It is useful since it provides, among other things, a means for preventing BDIs.

1. Bismuth and Strasberg classification

Abbreviations: RHD − right hepatic duct; CBD − common bile duct; CHD − common hepatic duct. 2. Stewart-Way classification: mechanism of injury

Abbreviations: CBD − common bile duct; CHD − common hepatic duct; RHD − right hepatic duct; LHD − left hepatic duct; RHA − right hepatic artery. There are several recommendations for carrying out an LC while eliminating the risk of a BDI. A fundamental one is the Strasberg’s “critical view of safety” technique [9], in which Calot’s triangle is cleared and exposed, the lower third of the gallbladder is separated from the liver bed and, finally, only two structures enter the gallbladder. It is not necessary to dissect and see the common biliary duct since such a procedure may disturb bile duct perfusion. Another recommendation is to dissect very close to the infundibulum (“infundibular technique” or “antegrade cholecystectomy”) in which the gallbladder is left hanging on the cystic artery and duct at the end of the procedure. The use of intraoperative cholangiography helps to show the anatomy of the biliary system and is valuable for the detection of any common bile duct stones. If the anatomical conditions are unclear, conversion to the open approach is recommended [10,11].

The primary risk factor for BDI is the presence of anatomical variants of the biliary tract, followed by surgery undertaken during an acute inflammation, severe obesity, previous surgery on the biliary tract and experience of the surgeon.

In our case, the patient had a very rare anatomic anomaly known as gallbladder agenesis (GA). The incidence is less than 1 per 6500 live births [12]. Most patients are asymptomatic, but 20% to 50% can experience symptoms of right upper quadrant pain that can be mistaken for cholecystitis or symptomatic cholelithiasis [13]. Patients with GA are often misdiagnosed due to misleading or inconclusive ultrasonography. Hence GA is often diagnosed intraoperatively. Surgery can be very risky in these patients since unnecessary dissection, carried out during a search for the non-existent gallbladder, can result in injury to the bile duct, hepatic vasculature or small bowel.

If the lesion of the biliary tree is not found during the surgery, subsequent clinical presentation depends on the extent of the BDI, alternatively intensified by a coincident vascular injury. The first symptoms are quite non-specific. They can include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal discomfort. If bile appears in the abdominal drain inserted during the cholecystectomy, biliary leakage is suspected. In case of a stricture in the biliary tree jaundice, pain in the right-upper quadrant and fever may appear. If there is any change in clinical presentation after the operation, it is advisable to suspect a possible BDI [10]. The patient may present with cholangitis or cirrhosis surprisingly late (months or even years after the biliary surgery [7]). Vascular injury can occur simultaneously with a BDI, most frequently on the right hepatic artery. These cases may also present with associated hepatic abscesses, bleeding, haemobilia and right hepatic lobe ischemia [14].

The most optimal results can be attained when BDI is recognized intraoperatively and resolved immediately. This occurs unfortunately in only about 25% of cases [15]. Immediate repair performed by an experienced surgeon has a better prognosis since there is no inflammation at that time.

Abdominal ultrasonography is the basic diagnostic tool of choice. More sensitive is the abdominal CT that can also identify associated vascular lesions. MRCP, ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) should be utilized in order to view the complete morphology of the biliary tract. There is no place for an exploratory laparotomy, as it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. BDI treatment requires an experienced team of skilled hepatobiliary surgeons and interventional radiologists. Hence, BDIs should be referred to high-volume hepatobiliary centres [16]. However, even in such medical centres, the incidence of strictures after repair surgery can be as high as 20% [17,18].

The most common methods to deal with BDIs are endoscopic procedures such as biliary stent placement, biliary sphincterotomy and nasobiliary drainage. They reduce the transpapillary pressure gradient and improve transpapillary flow, which decreases extravasation out of the biliary tract and allows healing. They are the treatment of choice, for example, for cystic duct leaks.

In case of more serious injuries, for which endoscopic procedures cannot be implemented, surgical intervention is required. In case of partial or complete transection of the bile duct, it is possible to perform a direct end-to-end ductal anastomosis, but only if the anastomosed edges are healthy and free of any inflammation, ischemia or fibrosis. Moreover, the anastomosis must be tension-free and properly vascularized [19]. If the above-mentioned procedure cannot be performed, biliodigestive anastomosis must be carried out. In most of the cases, this means a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Success of the surgical procedures depends on, among other things, eradication of any intra-abdominal infection, complete preoperative cholangiography, and a proper surgical technique used by an experienced biliary surgeon. Hepatectomy is rarely required, but if reconstructive approaches fail or extensive liver necrosis appears, the procedure needs to be performed. Liver transplantation remains the ultimate rescue therapy [20].

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a case report of a patient who sustained an extensive BDI after LC. The main risk factor for BDI is the presence of anatomical variants of the biliary tract. This was the case of our patient who had gallbladder agenesis, an extremely rare anatomic anomaly. Prior to LC, the surgeon was unaware of the absence of the gallbladder because preoperative abdominal ultrasonography indicated a shrunken gallbladder with small cholecystolithiasis. Although the anatomy during surgery was unclear, an effort to find the gallbladder and complete the LC unfortunately led to an extensive BDI.

This case report reminds us that although LC is one of the most common procedures in abdominal surgery, caution must always be exercised, especially with respect to the anatomy of the biliary tree, in order to prevent injury. If the anatomical relations are unclear, the surgeon must not hesitate with the conversion to an open approach. In the case of BDI, early recognition and treatment in a department with adequately experienced hepatobiliary specialists are crucial for a positive outcome.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brian Kavalir for his proofreading services.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in connection with this paper and that the article has not been published in any other journal, except congress abstracts and clinical guidelines.

MUDr. Adam Drs

Klinika transplantační chirurgie

Institut klinické a experimentální medicíny

Vídeňská 1958/9

140 21 Praha 4

e-mail: drsa@ikem.cz

Sources

- Huszár O, Kokas B, Mátrai P, et al. Meta-analysis of the long term success rate of different interventions in benign biliary strictures. PLoS One 2017;12(1):e0169618. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169618.

- Waage A, Nilsson M. Iatrogenic bile duct injury: a population-based study of 152 776 cholecystectomies in the Swedish Inpatient Registry. Arch Surg. 2006;141 : 1207–1213. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.12.1207.

- Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, et al. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of an Italian national survey on 56,591 cholecystectomies. Arch Surg. 2005;140 : 986–992. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.10.986.

- Tantia O, Jain M, Khanna S, et al. Iatrogenic biliary injury: 13,305 cholecystectomies experienced by a single surgical team over more than 13 years. Surg Endosc. 2008;22 : 1077–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9740-8.

- Roslyn JJ, Binns GS, Hughes EF, et al. Open cholecystectomy. A contemporary analysis of 42,474 patients. Ann Surg. 1993; 218 : 129−137.

- Bismuth H, Majno PE. Biliary strictures: classification based on the principles of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2001;25(10):1241−1244. doi:10.1007/s00268-001-0102-8.

- Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(1):101–125.

- Way LW, Stewart L, Gantert W, et al. Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Ann Surg. 2003;237(4):460−469. doi:10.1097/01.SLA.0000060680.92690.E9.

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(1):132−138. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.053.

- Pesce A, Palmucci S, La Greca G, et al. Iatrogenic bile duct injury: impact and management challenges. Clinical and experimental gastroenterology 2019;11 : 121–128. doi:10.2147/CEG.S169492.

- Šváb J, Pešková M, Krška Z, et al. Prevence, diagnostika a chirurgická léčba poranění žlučovodů během laparoskopické cholecystektomie. Léčení poranění papily v důsledku invazivní endoskopie. Část 1. – Prevence a diagnostika poranění žlučovodů. Rozhl Chir. 2005;84(4):176–181.

- Bennion RS, Thompson JE Jr, Tompkins RK. Agenesis of the gallbladder without extrahepatic biliary atresia. Arch Surg. 988;123(10):1257–60.

- Kasi PM, Ramirez R, Rogal SS, et al. Gallbladder agenesis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011;5(3):654−662. doi:10.1159/000334988.

- Halasz NA. Cholecystectomy and hepatic artery injuries. Arch Surg. 1991;126(2):137–138.

- Stewart L. Iatrogenic biliary injuries: identification, classification, and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94(2):297–310. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2014.01.008.

- Karanikas M, Bozali F, Vamvakerou V, et al. Biliary tract injuries after lap cholecystectomy-types, surgical intervention and timing. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(9):163. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.05.07.

- Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, et al. Advantages of multidisciplinary management of bile duct injuries occurring during cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2008;195(6):763–769. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.05.046.

- Schmidt SC, Langrehr JM, Hintze RE, et al. Long-term results and risk factors influencing outcome of major bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy [retracted in: Br J Surg. 2006;93(12):1562]. Br J Surg. 2005;92(1):76–82. doi:10.1002/bjs.4775.

- Jabłonska B. End-to-end ductal anastomosis in biliary reconstruction: indications and limitations. Can J Surg. 2014;57(4):271–277. doi:10.1503/cjs.016613.

- Renz BW, Bösch F, Angele MK. Bile duct injury after cholecystectomy: Surgical therapy. Visc Med. 2017;33(3):184–190. doi:10.1159/000471818.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgery

Article was published inPerspectives in Surgery

2020 Issue 9-

All articles in this issue

- Circulating matrix metaloproteinases as biomarkers in colorectalcancer

- Changes in normothermia during surgery

- Surgical treatment of extensive perianal hidradenitis

- Je nutné zjišťovat dopady covidu-19 na chirurgická pracoviště?

- Incarcerated lumbar hernia in the Petit´s triangle as a cause of large bowel obstruction

- Recommendations for patient management after manual reduction of incarcerated inguinal hernia: a literature review

- Liver transplantation using grafts from donors after circulatory death – the first Czech Republic experience

- Extensive bile duct injury resulting from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy resolved by a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy: a case report

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Surgical treatment of extensive perianal hidradenitis

- Incarcerated lumbar hernia in the Petit´s triangle as a cause of large bowel obstruction

- Changes in normothermia during surgery

- Extensive bile duct injury resulting from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy resolved by a Roux-en-Y tri-hepaticojejunostomy: a case report

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career