-

Medical journals

- Career

Getting “Un” Constipated in the 21st Century (Constipation… the “Low-Serotonin Syndrome”)

Authors: Z. Bic 1,2,3; S. Bizal 3,4

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Population Health and Disease Prevention, Public Health Program, College of Health Sciences, University of California, Irvine, USA http://www. cohs. uci. edu/publichealth/ 1; The American College of Lifestyle Medicine, www. lifestylemedicine. org 2; Wellness Coaching Institute, USA www. wellnesscoachinginstitute. com 3; The Bizal Group, Inc., USA 4

Published in: Gastroent Hepatol 2010; 64(4): 10-17

Category: Original Article

Overview

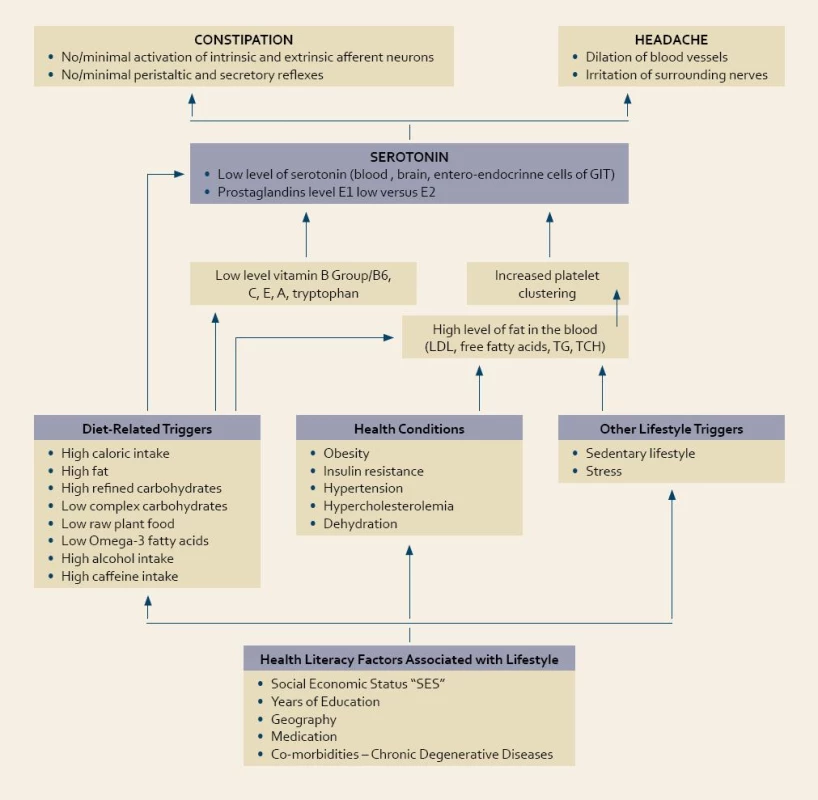

Constipation is a common syndrome, afflicting millions – that has so far defied a definitive cure, causing millions of physician visits per year, spending millions of dollars on over the counter medication, having economic consequences to the community/individuals and decreasing the quality of life. Hypothesis: Can a proper application of wellness/lifestyle medicine decrease the risk of development of constipation, reverse the already establish constipation and improve the quality of life? Methods: We investigated the public health problem with constipation in 21st century. We reviewed the recent literature on constipation from the perspectives of epidemiology, statistics, economic consequences, SES (social economic status), health literacy and education level, geographic area, gender, eating behavior, physical activity, stress level, co-morbidities, medication use and basic principles of the nature. Two reviewers performed reference search on Scholar Google and PubMed. Results: We developed a theoretical model of constipation – the public health problem in the 21st century from the perspectives of risk factors, prevention, treatment and application of wellness/lifestyle medicine (tab. 1). Conclusion: Constipation needs to be seen from completely different perspectives. We propose a new wellness/lifestyle medicine approach for prevention and treatment of constipation. It is necessary that health care providers will start to apply this approach into their medical model of treatment. We also suggest that constipation should not be seen as an isolated symptom, but as a first signal of potential biochemical imbalances in the body, which can lead to development of chronic diseases.

Key words:

constipation – serotonin – lifestyle interventions – wellness – nutrition – physical activity – stressIntroduction

The purpose of our research paper is to inter-connect results from previous research on constipation, to describe how constipation has been seen until today and to show how constipation needs to be seen in 21st century. The research leads us back to the natural principles of constipation. Based on the acquired information – we propose a new perception of constipation which is developed on the evidence based wellness/lifestyle medicine.

Constipation is defined as less than three bowel movements per week with symptoms of pain, straining, passage of hard stool [1]. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force defines constipation as unsatisfactory defecation characterized by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both. Constipation is termed chronic when symptoms have been present for at least 3 months [36]. Factors associated with constipation include, although are not limited to:

Economic Factors

The economic consequences of constipation in United States are a significant problem because over 330 million dollars is spent each year over the counter medication [4]. Constipation causes 2.5 million physician visits per year and it costs on average $ 2,752 per patient [5,6]. Constipation causes 92,000 hospitalizations/year and laxative sales of several hundred million of dollars a year in United States [19].

Social Economic Status “SES”

Social economic status influences the prevalence of constipation. Low income group have higher rates of constipation than wealthier group, for example study by Sandler, where the population came from NHANES I income for < 7 K was connected with 1.6 % prevalence of constipation versus income of > 15 K was connected with 8.6 % prevalence of constipation [3].

Health Literacy and Years of Education

There is an inverse relationship between the level of health literacy and years of education of an individual and prevalence of constipation [3]. This trend was reported in a number of studies 1975 NHIS and in NHANES I [7]. Self-report of constipation is more common in non-white, less educated, and less wealthy North Americans [3].

Quality of Life

Quality of life was measured and is decreased on mental and physical sub-scores on SF-36 level based on the study by Irvine et al [8]. Constipation impairs quality of life. Self-reported constipation and functional constipation as defined by the Rome Criteria lead to significant impairment of quality of life [22].

Geography

Epidemiological studies shows that constipation is a significant problem in Europe, Oceania (New Zealand and Australia) and North America [2,3]. In the general population in Europe the mean value of prevalence for constipation is 17.1 % and 15.3 % for Oceania [2]. Self-reported constipation, based upon the questionnaire survey, was as high as 35.0 % in Europe and 31.0 % in the general population in Sydney, Australia [2]. The epidemiological studies for North America show the prevalence of constipation to be 12.0–19.0 % among the general population [3]. The specific region (location and culture) plays its role in prevalence of constipation. The prevalence of constipation was seen in the USA from the highest in the South (2.19 %), Midwest (1.97 %), in the West (1.84 %) and the lowest in the Northeast (1.44 %) [11].

Gender

There is a higher prevalence of constipation among women, with female/male ratios between 1.01–3.77 and the median being 2.20 [3].

Age

The age of an individual plays its role in the prevalence of constipation. Based on the study by Hammond there is a gradual increase in constipation after the age 50 [9]. The occurrence of constipation increases with advancing age, showing and exponential increase in prevalence after the age of 65 [39].

Co-morbidities and Medication Causing Constipation

Diabetes II is recognized as a co-morbidity with constipation [13]. Diabetic patients have delayed response in postprandial colonic motility. This study concluded that patients with Diabetes II may have an autonomic neuropathy which may lead to an absent postprandial gastro-colonic response [12]. Metabolic syndrome – a common metabolic disorder with abnormalities that includes central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance. This metabolic syndrome is a major risk for diabetes II, cardiovascular disease and cancer [18]. Fibromyalgia frequently coexist with constipation – (73 %) of fibromyalgia patients reports altered bowel function [16]. Low serotonin level is correlated with constipation. Patients with chronic slow-transit constipation showed an abnormal colonic endocrine cells – fewer serotonin-immunoreactive cells [17]. Individuals with a history of diabetes or frequent constipation were at increased risk for colorectal cancer [43]. High energy intake, large body mass, physical inactivity, nutritional imbalance similar to the involved in Diabetes II may lead to colorectal cancer [43]. Pellagra is connected with deficiency in vitamin B groups, low omega-3 fatty acids and symptoms of constipation [49,50]. Pellagra is connected with low level of serotonin [51].

Drugs with anti-cholinergic activity – drugs that nearly 60 % of nursing homes residents received during one year are increasing risk for constipation [14]. The number of drugs with anticholinergic activity is available without prescription (for example: antihistamines in cold/flu (Benylin, Actifed); treatments for sleep (Nytol, Sominex); for digestion (Tagamet, Zantac, Pepcid); and tricyclic antidepressants [15]. Constipation and headache were associated significantly with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists compared with other anti-emetics [42].

Eating Habits and Behavior

Based on the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-1) people who ate more fruits and vegetables had fewer complaints of constipation [28]. Subjects receiving probiotics as dietary supplements exhibited 24% increase in defecation frequency [29]. A fibre-rich porridge was effective, well liked, tolerated and reduced the need for laxatives in geriatric patients [30]. The intake of dietary fibre has been declined from about 40 g/day (100 years ago) to 15–20 g/day to most western countries [31]. Constipated children have significantly lower intakes of dietary fibre and micronutrients including vitamin C, folate, and magnesium than non-constipated children, which was attributable to under-consumption of plant food. Milk intake was higher in the constipated children [32]. Cocoa husk dietary supplement that is high in dietary fiber has a beneficial effect on chronic idiopathic constipation in children [33]. Fibre containing foodstuffs may favorably influence the bacterial activity in the colon and it is beneficial in constipation [48]. Western type of diet contains much less ω-3 fatty acids than the diet of a century ago [54]. Both alcohol and caffeine intake has effect on constipation. Mouth-to-cecum transit was significantly prolonged in alcoholics (p < 0.001) [61,62]. The pellagra triggered by alcoholism has influence on the serotonin metabolism. The 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine) concentration is reduced in platelets, 5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleactic acid) excretion in urine is below normal and 5-HIAA concentration in CFS is reduced in pellagrins [61]. Premenstrual syndrome consists of different symptoms; including depression, tiredness, irritability, anxiety as well as constipation. High caffeine consumption also increased the risk of constipation in premenstrual syndrome: increasing consumption from 0.5–4.0 to 4.5–15 drinks of caffeinated beverages increased the risk of the prevalence of constipation from 0.3–1.3 measured as odds ratio. In this study, consumption was defined as a “drink” [63].

Physical Activity

The level of an individual’s physical activity has influence on prevalence of constipation based on the study by Sandler where decreased of recreational and non-recreational exercise activity favored constipation respectively odds ratio (OR) 1.16 and 1.2 [10]. Prolonged physical inactivity can reduce colonic transit [23]. Increased physical activity is associated with decreased rates of constipation [24]. A bowel management program with increased amount of fiber, fluids and exercise was applied in the nursing home. The results demonstrated a decrease in consumption of laxatives and increase in numbers of spontaneous bowel movements [25]. Physical therapy incorporating abdominal massage appeared to be helpful for patient’s constipation [47].

Stress Level

Defective and ineffective use of coping strategies may be an important etiological factor in functional constipation. People suffering from constipation have higher anxiety and depression scores and lower scores on quality of life [26]. Psychological factors and in particular anxiety and depression are considered predisposing to constipation [34]. Young people going to the university or starting a hospital job reported increase in constipation [35].

Hypothesis

Can a proper application of wellness/lifestyle medicine decrease the risk of development of constipation, reverse the already establish constipation and improve the quality of life?

Methods

Performed Scholar Google, PubMed search references with topics “constipation”.

Results/Hypotheses

Based on the recent analysis of collected research articles on constipation we developed a theoretical model of the constipation.

We hypothesize that a common denominator in the pathophysiology of constipation – namely, low level of serotonin [20] which can be caused by: 1. high levels of free fatty acids and blood lipids, 2. low level of natural sources for serotonin synthesis, namely low levels of B group vitamins, vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin E and tryptophan; and 3. low level of omega-3 fatty acids as a source for synthesis of Prostaglandins E1 (PGE1) which helps to balance the level of serotonin.

Currently, new medication use to relieve the symptoms of constipation is based on specific serotonin receptor agonist or serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors, both of which are design to improve function of gastrointestinal system [38].

Medication used for treating constipation

Serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors – a new class of therapeutic agents that target and alter serotonin signaling – may provide a new effective therapy [27]. A partial 5-HT4 receptor agonist has been approved by the FDA for either the treatment of functional constipation or for the treatment of women with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome [21]. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT4) participates in several functions of gastrointestinal tract including control of normal gut motor activity. Abnormalities in serotonergic function contribute to symptoms of functional bowel disorders [20]. Selective serotonin agonist relieve constipation. Up to 62 % of patients reported relief from constipation with four weeks of TD-5180 (selective serotonin agonist) [38]. There are therapeutic benefits of 5-HT4 agonists in irritable bowel syndrome associated with constipation (IBS-C) [40]. Tegaderod, a 5-HT4 agonist, has been approved and will soon be available for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) [41,52]. Prucalopride (which acts as a selective 5-HT4 agonist) significantly improves bowel function and reduces the severity of symptoms in patients with severe chronic constipation [44]. Lubiprostone, a prostaglandin E1, was approved for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation and for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation [53]. The development and clinical use of the serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonists, collectively known as “triptans”, are also being used to treat patients with migraine headaches [45,46]. Serotonin activates intrinsic and extrinsic afferent neurons, initiates peristaltic and secretory reflexes, and transmits information to the central nervous system.

Dietary factors contributing to low levels of serotonin

High level of free fatty acids and blood lipids (high level of triglycerides, high level of cholesterols) are increasing the risk of platelet aggregability. Serotonin is stored in platelets. When platelet aggregability is increased, platelets are destroyed/damaged and the level of stored platelet components decreased. Changes in these platelet components can lead to low level of serotonin in blood, nervous system and in cells of gastrointestinal system [55,38]. Low level of serotonin is connected with minimal peristaltic and secretory reflexes and increases the risk for constipation [38,40]. Low level of natural sources for serotonin synthesis, namely low levels of B group vitamins, vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin E and tryptophan from food/dietary supplements will lead to decrease in production of serotonin [57]. Low levels of, or deficiency in, vitamin B6 decreases the concentration of the enzyme, pyridoxal phosphate, which takes an important place in synthesis of serotonin [24,55]. Diets high in saturated fat and low in omega-3 fatty acids increase: (a) PGE2 which role is to increase platelet aggregation and (b) decrease the level of Prostaglandins PGE1 and PGE3 which role is to help to balance the level of serotonin and prevent platelet aggregation [55,58].

Dietary factor contributing to higher levels of serotonin

Plasma serotonin levels can be increased not only by low fat diet that maintains platelet integrity but also by increasing complex carbohydrate diet: namely increases in dietary vitamin B6 and tryptophan. Tryptophan is a precursor of serotonin and vitamin B6 takes part in synthesis of serotonin [55,57]. Lowering blood lipid levels can be achieved by consuming more organically grown, raw, fresh fruits, vegetable, nuts and seeds and simultaneously reducing the intake of animal products (primarily non-organic commercially grown/processed meat and dairy products) and processed/synthetic foods. It is important to increase those naturally occurring precursors for serotonin synthesis such as nutrients – B vitamins, vitamin C, vitamin A, vitamin E, tryptophan, etc. – found in raw fresh fruits, vegetable, legumes, beans, nuts and seeds [57,59]. Increasing the intake of omega-3 essential fatty acids from plant sources (i.e. seeds, nuts, soy beans) and non-plant sources (i.e. certain cold-water fish) while decreasing the intake of saturated fats and hydrogenated fats [59] will lead to higher levels of serotonin (tab. 1).

1. Theoretical Model of Constipation – “Low-Serotonin Syndrome©” the Public Health Problem in the 21st Century. (Copyright ©2010 by Zuzana Bic.) Tab. 1. Teoretický model zácpy – syndrom nízké hladiny serotoninu, problém zdravotnictví 21. století.

Factors contributing indirectly to constipation – no/minimal activation of intrinsic and extrinsic afferent neurons with no/minimal peristaltic and secretory reflexes

High dietary fat intake, high caloric intake, high intake of refined carbohydrates, low complex carbohydrates, low intake of raw plant food, low intake of omega-3 fatty acid, obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, prolonged hunger, dehydration, sedentary lifestyle, high level of stress, depression and anxiety all of the above increase the risk for constipation through a common denominator – increasing the level of free fatty acids, blood lipids and causing the platelet aggregation with subsequent occurrence of low serotonin syndrome [55]. If each the above factor could be minimized – the risk for constipation could be decreased (tab. 1).

Health literacy and other factors connected with lifestyle factors leading to constipation

Based on our research of the literature we found out that SES (social economic status) is influencing the prevalence of constipation, in the way that low income group have higher rates of constipation [3]. The reason could be that in this socio-economic group it is difficult to get the health literacy level that could lead this group to eat healthy, to have enough of physical activity and to keep a life with lower level of stress.

This low SES group lives in the areas where there is an abundance of low-cost unhealthy fast food sources. Geography also appears to play a role in constipation. The greatest prevalence of constipation in the USA exists in the following regions (in order of highest to lowest prevalence): South, Midwest, West and Northeast. If we compare culture and lifestyle to eating styles in each of these regions a correlation exists between the higher consumption of unhealthy foods (cooked, processed, animal, low fiber vs. raw, unprocessed, plant, high fiber) with the highest prevalence of obesity which also correlates – based upon our theoretical model (tab. 1) – to an increased risk of constipation. From the view of using the medication, it is apparent that medication with anti-cholinergic activity and with the effect of decreasing the serotonin level are also connected with increased risk for constipation [14,15]. Diabetes II is already recognized as a risk factor for constipation [13]. If we define all the lifestyle risk factors for Diabetes II – such as central obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance – we have the risk factors for constipation. Gradual increase of constipation after the age of 50 is supporting also our theory that keeping on unhealthy eating style, sedentary lifestyle and high level of stress for a long period of time can increase the risk for constipation.

Based on the studies by Bic et al “In search of the ideal treatment for migraine headache” and “The influence of a low-fat diet on incidence and severity of migraine headaches” where headaches are connected with a low level of serotonin; we hypothesize that constipation and headaches have similar risk factors, similar common denominator and both (constipation and headaches) could be seen as early warning signal for development of chronic diseases later and also both are decreasing the quality of life (tab. 1) [55,56].

Discussion

Basic Principles of Nature

The conventional wisdom about “constipation” – our current medical model – is based upon a theory that evolved within the scientific context of Newtonian Physics. This conventional approach merely described this gastric condition based upon symptomatology and pharmacologically treats the symptom, in lieu of addressing the cause. As our understanding of health, healing and the (w)holistic nature of humankind has expanded and evolved, our understanding and treatment of “constipation” must also evolve. We must re-contextualize what we have come to recognize as the symptoms that we call “constipation” within this greater understanding. This re-contextualization must be framed within an awareness of the evolution of man’s digestive tract, as designed by nature, by asking a new level of question: “What were humans designed to eat based upon the functional, anatomical, bio-chemical and physiological evolution of man’s digestive tract in the natural setting/environment, irrespective of man’s ability to manipulate his food chain throughout history?” A simple analysis of man’s digestive tract when compared to that of both carnivores (meat eaters) and herbivores (plant eaters) reveals a close alignment to that of the plant eaters (tab. 2). Why would this be, if not intended as such? Are we to question the integrity of natures design? What can we extrapolate from this comparative analysis? In addition, and with the same openness to challenging existing dogma and with the same scientific rigor that precede all paradigm shifts in the direction of higher levels of truth, does not the empirical as well as the scientific research data now support the correlation between a lifestyle comprised of mostly uncooked and unprocessed plant foods with a significantly lower incidence of all digestive tract ailments?

2. Similarities and Differences between Carnivores, Herbivores and Man. Tab. 2. Podobnosti a rozdíly mezi masožravci, býložravci a člověkem.

*Ptyalin is a digestive enzyme for breaking down starches (carbohydrates). Source: What’s Wrong with Eating Meat? by Vistara Parham, PCAP Publications, Corona, New York, 1981, pp.3–11. Reprinted with permission. Conclusion

“A New Perspective on Constipation”

Although medicine has made great strides in the past and will continue to make great strides today and in the future toward not only eliminating the suffering of man but also improving the quality of life, is it possible that our own unrecognized self-limiting thinking, based upon an outdated scientific paradigm, is preventing and precluding a greater understanding of the confluence of symptoms that we label “constipation”, its etiology, its cures and its prevention?

If it is true that our state of health, or lack thereof, is determined at a significant level, by the quality of the chemistry within the body; and if it is also true that the quality of the chemistry within our bodies is determined by the quality of the (1) the air that we breath, (2) the fluids that we drink, (3) the “foods” that we eat, and the (4) substances we apply to the external body – all of which are aspects of lifestyle and behavior – then are we not, in fact, ultimately in control of the quality of health of the body that we experience? Why does the prevalence of constipation continue to increase among the population?

We would like to conclude by inviting the research community to consider the following questions as part of clinical design parameters for future scientific research to obtain appropriate evidence-based data that supports our conclusion: 1. Are we eating in alignment with the requirements of our digestive tract as originally designed by nature? 2. Are human eating habits violating principles of nature?

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank doc. MUDr. Milan Kment, CSc., The Editor-in-Chief of Czech and Slovak Gastroenterology and Hepatology Journal, for giving us the opportunity to share our research as well as our thoughts.Zuzana Bic, Dr.P.H.,MUDr.1,2,3and Stephen Bizal, D.C.3,4

1Department of Population Health and Disease Prevention, Public Health Program, College of Health Sciences, University of California, Irvine, USA http://www.cohs.uci.edu/publichealth/

2 The American College of Lifestyle Medicine, www.lifestylemedicine.org

3 Wellness Coaching Institute, USA www.wellnesscoachinginstitute.com

4 The Bizal Group, Inc., USA

zbic@uci.edu

sbizal@drbizal.com

Sources

1. Thompson W, Longstreth G, Drossman D. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999; 45 : 43–47.

2. Peppas G, Alexious VG, Mourtzoukou E et al. Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterology 2008, 8 : 5.

3. Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99(4): 750–759.

4. Curry CE. Laxatives. In: Handook of non-prescription Drugs, 8th Ed.Washington, DC:American Pharmaceutical Association, 1986 : 75–97.

5. Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Sandler RS et al. Epidemiology of constipation (EPOC) study in United States: Relation of clinical subtypes to socio-demographic features. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94(12): 3530–3540.

6. Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci 1989; 34(4): 606–611.

7. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 1989; 11(5): 525–536.

8. Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P et al. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: Focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97(8): 1986–1993.

9. Hammond E. Some preliminary findings on physical complaints from a prospective study of 1,064,004 men and women. Am J Pub health 1964; 54 : 11–23.

10. Sandler RS, Jordan MC, Shelton BJ. Demographic and dietary determinants of constipation in the US population. Am J Public Health 1990; 80(2): 185–189.

11. Johanson JF. Geographic distribution of constipation in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93(2): 188–191.

12. Battle WM, Sanppe WJ, Alavi A et al. Colonic dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology 1980; 79(6): 1217–1221.

13. Camilleri M. Gastrointestinal problems in Diabetes. Endocrinology & Metabolism Clinics of North America 1996; 25(2): 361–378.

14. Blazedr DG, Federspiel CF, Ray WA et al. Thenrisk of anticholinergic toxicity in then elederly – a study of prescribed practices in two populations. J Gerontol 1983; 38(1): 31–35.

15. Mintzer J, Burns A. Anticholinergic side-efects of drugs in elderly people. Journal of the Royal Socirty of Medicne 2000; 93(9): 457–462.

16. Triadafilopoulos G, Simms RW, Goldenberg DL. Bowel dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 1991; 36(1): 59–64.

17. El-Salhy M, Norrgĺrd O, Spinnell S. Abnormal Colonic Endocrine Cells in patients with chronic Idiopathic Slow-Transit constipation. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1999; 34(10): 1007–1011.

18. Galisteo M, Duarte J, Zarzuelo A. Effects of dietary fibers on disturbances clustered in the metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem 2009; 19(2): 71–84.

19. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic Constipation. The New England Journal of Medicine 2003; 349(14): 1360–1368.

20. Hassler WL. Serotonin and GI tract. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2009; 11(5): 383–391.

21. Tonini M, Pace F. Drugs acting on serotonin receptors for treatment of functional GI disorders. Dig Dis 2006; 24(1-2): 59–69.

22. Talley NJ. Definitions, epidemiology, and impact of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004; Suppl 2: S3–S10.

23. Liu F, Kondo T, Toda Y. Brief physical inactivity prolongs colonic transit time in elderly active men. Int J Sports Med1993; 14(8): 465–467.

24. Muller-Lissner SA, Kamm MA, Scarpignato C et al. Myths and misconceptions about chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100(1): 232–242.

25. Karam SE, Nies DM, student/staff collaboration. A pilot bowel management program. J Gerontol Nurs 1994; 20(3): 32–40.

26. Chan AO, Hui WM, HU WH et al. Differing coping mechanisms, stress level and anorectal physiology in patients with functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(34): 5362–5366.

27. Sikander A, Rana SV, Prasad KK. Role of serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 2009; 403(1-2): 47-55.

28. Sandler RS, Jordan MC, Shelton BJ. Demographic and dietary determinants of constipation in the US population. Am J Public Health 1990; 80(2): 185–189.

29. Ouwehand AC, Lagström H, Suomalainen T et al. Effect of Probiotics on constipation, fecal azoreductase activity and fecal mucin content in the elderly. Ann Nutri Metab 2002; 46(3–4): 159–162.

30. Wisten A, Messner T. Fruit and fibre (Pajal porridge) in the prevention of constipation. Scand J Caring Sci 2005; 19(1): 71–76.

31. Taylor R. Management of constipation:high fibre diet works. Br Med J 1990; 300(6731): 1063–104, 1990.

32. Lee WTK, Ip KS, Chan JSH et al. Increased prevalence of constipation in pre-school children is attributable to under-consumption of plant foods: a community-based study. J Pediatr Child Health 2008; 44 : 170–175.

33. Castillejo G, Bullo M, Anguera A et al. A randomized double-blind trial to evaluate the effect of a supplement of cocoa husk that is rich in dietary fiber on colonic transit in constipated pediatric patients. Pediatrics 2006; 118(3): e641–e648.

34. Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Are anxiety and depression related to gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population? Scand J Gastroenterol 2002; 37(3): 294–298.

35. Sandler RS, Drossman DA. Bowel habits in young adults not seeking health care. Dig Dis Sci 1987; 32(8): 841–845.

36. Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S et al. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract 1996; 13(2): 156–159.

37. American College of Gastroenterology Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Task Force. Evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97(Suppl): S1–S5.

38. Goldberg M et al. “In patients with chronic constipation, TD-5108, a selective 5-HT 4 agonist with high intrinsic activity, increases bowel movement frequency and the proportion of patients with adequate relief”. American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting and Postgraduate Course 2007; 12-17; Philadelphia, Abstract 56.

39. Johanson JF, Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Clinical Epidemiology of chronic constipation. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 1989; 11(5): 525–536.

40. Siller R. Serotonergic agents and irritable bowle syndrome: what goes wrong? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008; 8(6): 709–714.

41. Ducrotte P. Irritable bowel syndrome: current treatment options. Presse med 2007; 36(11 Pt 2): 1619–1626.

42. Tramer M. Efficacy of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2009; 34(12): 1836–1844.

43. Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN et al. Associations of sedentary liefestyle, obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and diabetes with the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1997; 57(21): 4787-4794.

44. Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A et al. A pleacebocontrolled trial of Prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(22): 2344–2354.

45. Goadsby PJ. Serotonin 5 HT receptor agonists in migraine: comparative pharmacology and its therapeutic implications. CNS drugs 1998; 10(4): 271–286.

46. Ferrari M, Roon K, Lipton R et al. Oral triptans (serotonin 5-HT agonists) in acute migraine treatment: a meta-analysis of 53 trials. Lancet 2001; 358(9294): 1668–1675.

47. Harrington KL, Haskvitz EM. Managing a patient’s constipation with physical therapy. Phys Ther 2006; 86(11): 1511–1519.

48. Cummings JH. Constipation, dietary fibre and the control of large bowel function. Postgraduate Medical Journal 1984; 60(709): 811–819.

49. Rudin DO. The major psychoses and neuroses as omega-3 essential fatty acid deficiency syndrome: substrate pellagra. Biol Psychiatry 1981; 16(9): 837–850.

50. Jagielska G, Tomaszewicz-Libudzic CA, Brzozowska A. Pellagra – a rare complication of anorexia nervosa. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 16(7): 417–420.

51. Raghuram TC, Krishnaswarmy K. Serotonin metabolism in pellagra. Arch Neurol 1975; 32(10): 708–710.

52. Gershon JT. The serotonin signaling system: From basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology 2007; 132(1): 397–414.

53. Ginzburg R, Ambizas E. Clinical pharmavology of Lubiprostone, a chloride channel activator in defecation disorders. Expert Opin Drug MetabmToxicol 2008; 4(8): 1091–1097.

54. Phinney SD, Odin RS, Johnson SB et al. Reduced arachidonat in serum phospholipids and cholesteryl esters associated with vegetarian diets in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1990; 51(3): 385–392.

55. Bic Z, Blix G, Hopp HP et al. In search of the ideal treatment for migraine headache. Medical Hypothesis 1998, 50(1), 1–7.

56. Bic Z, Blix G, Hopp HP et al. The influence of a low-fat diet on incidence and severity of migraine headaches. J Womens health Gend Based Med 1999; 8(5): 623–630.

57. Wurtman RJ, Wurtman JJ. “Nutrition and brain”. Disorders of eating and nutrients in treatment of brain disease. Raven Press. New York, edited by RJ Wurtman and J.J Wurtman. Volume 3.

58. Stein EA, Shapero J, McNerney C et al. Changes in plasma lipid and lipoprotein fractions after alteration in dietary cholesterol, polyunsaturated, saturated, and total fat in free-living normal and hypercholesterolemic children. Am J Clin Nutr 1982; 35(6): 1375–1390.

59. Nettleton JA. Omega-3 fatty acids: comparison of plant and seafood sources in human nutrition, J Am Diet Assoc 1991; 91(3): 331–337.

60. Raghuram TC, Krishnaswamy K. Serotonin Metabolism in Pellagra. Arch Neurol 1975; 32(10): 708–710.

61. Ishii N, Nishikara Y. Pellagra among chronic alcoholics: clinical and pathological study of 20 necropsy cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1981; 44(3): 209–215.

62. Wegener M, Schaffstein J, Dilger U et al. Gastrointestinal transit of solid-liquid meal in chronic alcoholics. Dig Dis Sci 1991; 36(7): 917–923.

63. Rossignol AM. Caffeine containing beverages and premenstrual syndrome among young women. Am J Public Health 1985; 75(11): 1335–1337.

Labels

Paediatric gastroenterology Gastroenterology and hepatology Surgery

Article was published inGastroenterology and Hepatology

2010 Issue 4-

All articles in this issue

- The role of ultrasound in diagnostics of bowel disease

- Risk of combining clopidogrel with proton pump inhibitors – significance and possible solutions

- Report from CEURGEM 2010

- Czech and Slovak Endoskopic Days, Prague 24.–25. 6. 2010

- Eosinophilic gastroenteritis as a rare cause of ascites

- Getting “Un” Constipated in the 21st Century (Constipation… the “Low-Serotonin Syndrome”)

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- The role of ultrasound in diagnostics of bowel disease

- Risk of combining clopidogrel with proton pump inhibitors – significance and possible solutions

- Eosinophilic gastroenteritis as a rare cause of ascites

- Getting “Un” Constipated in the 21st Century (Constipation… the “Low-Serotonin Syndrome”)

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career