-

Medical journals

- Career

Successful Treatment of Meningoencephalitis due to Cryptococcus gattii with Ommaya Reservoir and Intrathecal Injection of Amphotericin B – a Case Report

Authors: Ch. Chang-Hua 1; W. Shao-Hung 2; Y. Hua-Cheng 3; W. Wang-Fu 4,5; Ch. Wei Liang 6; Y. Yung-Jen 5; Ch. Yu-Min 7; H. Chieh-Chen 8

Authors‘ workplace: Division of Infectious Diseases Department of Internal Medicine Changhua Christian Hospital Changhua, Taiwan 1; Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Biopharmaceuticals, National Chiayi University, Chiayi City, Taiwan 2; Department of Neurosurgery, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan 3; Department of Neurology, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan 4; Tsao-Tun Psychiatric Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Nan-Tou, Taiwan 5; Department of Medical Imaging Changhua Christian Hospital Changhua, Taiwan 6; Department of Pharmacy, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan 7; Department of Life Science, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung Taiwan 8

Published in: Cesk Slov Neurol N 2017; 80/113(3): 337-342

Category: Case Report

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2017337Overview

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is a potentially fatal disease. We report successful treatment with the Ommaya reservoir and intrathecal injection of amphotericin B for the control of refractory cerebral cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus gattii AFLP4/ VGI. A 63-year-old male patient presented with a 2-week history of fever and headache, and was he diagnosed with CM. Combined amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine treatment was initiated and followed by fluconazole therapy. After 7 months, he was refractory to traditional CM treatment and received salvage therapy with an Ommaya reservoir and intrathecal injection of amphotericin B. His neurological symptoms recovered gradually with no evidence of relapse during 12-month follow-up. The isolate was re-identified by culturing in canavanine-glycine-bromothymol Blue media and by molecular typing using URA5 as Cryptococcus gattii AFLP4/ VGI. The Ommaya reservoir could serve as an alternative treatment for Cryptococcus gattii AFLP4/ VGI-induced CM, which responds poorly to standard regimens.

Key words:

Ommaya reservoir – intrathecal injection of amphotericin B – Cryptococcus gattii AFLP4/VGI – meningoencephalitis – cryptococcoma

Chinese summary - 摘要

使用Ommaya reservoir和鞘內注射 amphotericin B成功治療隱球菌性腦膜炎 - 案例報告

陳昶華1, 王紹鴻2,顏華正3, 王文甫4,5,陳威良6, 楊詠仁5,陳昱旻7, 黃介辰8

隱球菌性腦膜炎,是一種會致命的疾病,我們報告一個案例,成功使用Ommaya reservoir和鞘內注射(intrathecal injection)amphotericin B,治療對標準治療配方的反應不佳的隱球菌性腦膜炎病患。這名63歲男性患者,起初有2週的發燒和頭痛,並被診斷出隱球菌性腦膜炎。給與標準治療配方amphotericin B 與 5-flucytosine治療後,再給予fluconazole治療。7個月後,病患對標準治療配方,反應不佳,出現神經症狀逐漸惡化 ; 病患接受Ommaya reservoir和鞘內注射 amphotericin B,病患的神經症狀逐漸恢復,並且病患在追蹤的12個月期間,沒有隱球菌性腦膜炎復發的跡象。此菌株經過重新鑑定,在canavanine-glycine-bromothymol培養基培養,和運用URA5進行分子分型鑑定等等後,此菌株鑑定為Cryptococcus gattii AFLP4/ VGI。我們建議在治療Cryptococcus gattii AFLP4/ VGI引起的隱球菌性腦膜炎並且病患對標準治療配方的反應不佳時候,Ommaya reservoir可以考慮作為隱球菌性腦膜炎的替代治療。Introduction

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is a potentially fatal disease caused by infection with Cryptococcus spp. Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) and Cryptococcus gattii (C. gattii) are the most commonly isolated pathogenic Cryptococcus species, and the taxonomy of their species complexes has been revised [1,2]. CM is a global invasive mycosis associated with significant morbidity and mortality [3,4] from neurological complications [4 – 6]. C. gattii, formerly known as C. neoformans var. gattii, has been recognized as an endemic pathogen since the 1990s [5 – 7]. Those infected with C. gattii tend to be younger patients with meningitis but without underlying conditions [8,9]. Whether the immune function of the host or different C. gattii subtypes contribute more to poor prognoses, pathogenesis is still being debated [10,11].

Intensive induction therapy with amphotericin B (AmB) and 5-flucytosine (5-FC) is a standard practice to improve the outcome of the central nervous system (CNS) infections caused by C. gattii [4,5,12,13]. However, response to this typical combination regimen varies and high mortality is seen in treated patients with complicated CM [4]. Owing to the low permeability of the blood-brain barrier to the majority of antifungal agents, these parenteral treatments are not always effective, resulting in treatment-refractory CM. Although the majority of CM treatment guidelines discouraged or rarely considered the use of adjunctive intrathecal or intraventricular administration of antifungal agents, this approach may be an option for patients with poor treatment response. The Ommaya reservoir, originally invented in 1963 by Pakistani neurosurgeon A. K. Ommaya, facilitates delivery of intrathecal medication (e. g. antibiotics, chemotherapy) [14].

Here, we present a case of a 63-year-old male patient with cerebral cryptococcosis caused by C. gattii (genotype AFLP4/ VGI), acute severe hydrocephalus, and cryptococcoma, who failed to respond to conventional parenteral treatments.

Case report

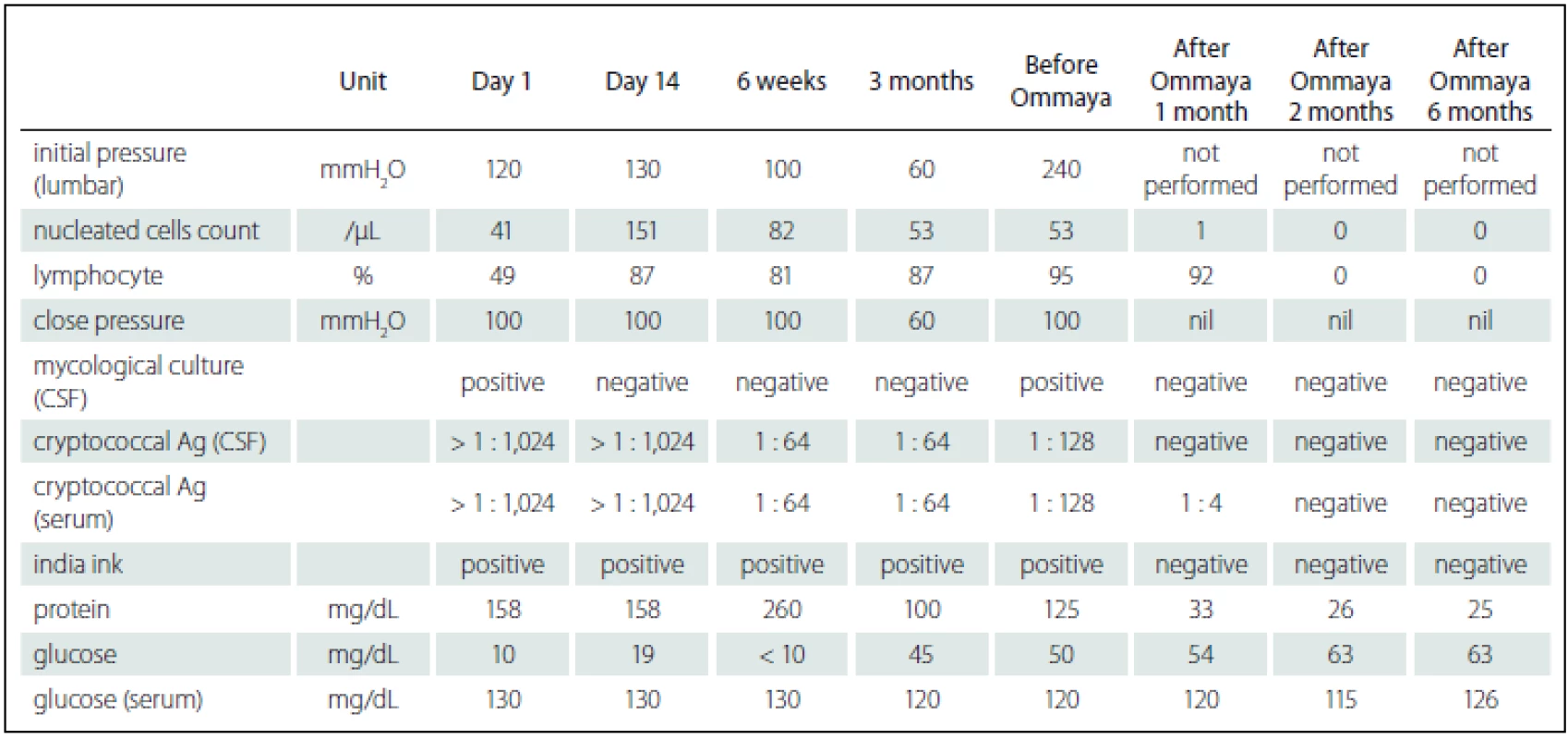

A previously healthy 63-year-old male patient developed a fever and headache that persisted for 3 weeks. Prior to his first hospitalisation at Changhua Christian Hospital, he had received treatment for 2 weeks, without a definite diagnosis. Upon his arrival at the emergency room, physical and neurological examinations revealed a fever (39°C), severe headache, neck stiffness, and a positive Brudzinski’s sign. He reported no history of blurred vision, double vision, neck pain, or change in consciousness.We performed computed tomography (CT) of the brain and a subsequent lumbar puncture. India ink-positive yeast was identified in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; Tab. 1) and CM was diagnosed. Later, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed enhanced cortical nodules and mild hydrocephalus (Fig. 1A). We also investigated potential risk factors for CM by assessing immunity parameters and testing for human imunnodeficiency virus (HIV) and other systemic or malignant diseases. All findings were negative. He was then hospitalized and treated with intravenous AmB (0.7 mg/ kg//day) and 5-FC (100 mg/ kg per day, 4-times a day). His clinical symptoms subsided 4 weeks later and a consolidation therapy regimen with oral fluconazole (FLC) (450 mg per day orally) was administered for 3 months following discharge. Owing to seizure attacks, he was re-hospitalized. Follow-up CSF analysis indicated that the cryptococcal infection was still present. We prescribed intravenous AmB (0.7 mg/ kg/ day) and oral 5-FC (100 mg/ kg/ day) for 2 weeks, followed by 6 weeks of treatment with intravenous FLC (6 mg/ kg/ day). He was then discharged, as the signs of clinical infection appeared to be under control. Oral FLC (450 mg/ day) was prescribed for consolidation therapy.

Fig. 1. Timeline of C. gattii AFLP4/VGI infection, the serial brain magnetic resonance imaging.

The serial magnetic resonance image (MR image) were analyzed. Fig. 1A showed initial gadolinium-enhanced T1 coronal MR images, and it showed enhanced nodules in the cortex (arrow) and mild hydrocephalus (arrow). Fig. 1B showed 1 month follow-up gadolinium-enhanced T1 axial MR image, and it also showed enhanced nodules in the cortex (arrow). Fig. 1C showed 6-months follow up gadolinium-enhanced T1 axial MR image, and it showed multiple new nodules and exacerbated hydrocephalus. Fig. 1D showed 15-months follow up brain MR image, and no new nodules and more exacerbated hydrocephalus. 1. Serial CSF findings of Cryptococcus gattii infection.

Ag – antigen. He was re-admitted 4 months after his second hospitalization owing to general weakness, changes in consciousness, and unfavorable CSF data (Tab. 1). Follow-up MRI showed multiple new nodules and exacerbated hydrocephalus (Fig. 1C). No evidence of cryptococcal infection in the peripheral system was found. Owing to his deteriorated clinical condition, persistent unfavorable CSF data, and MRI results indicating disease progression, his family agreed to treatment with intraventricular AmB. He was treated with intraventricular AmB (0.25 mg/ dose, 6 doses/ week) administered by Ommaya reservoir (Model number 44111, Medtronic PS Medical Inc.) and intravenous AmB (0.7 mg/ kg/ day) for 8 weeks. For each injection, we withdrew 10 mL of CSF from the Ommaya reservoir, slowly infused a combination of 0.5 mL distilled water and 0.25 mg AmB into the Ommaya reservoir, and flushed with 1 mL CSF using the previously withdrawn CSF. The total dose of AmB delivered intraventricularly and that delivered intravenously was 12 mg and 3,000 mg, resp. His response to treatment was fair and he was finally discharged after 71 days of hospitalization. During the follow-up of 2 years, he received consolidated oral FLC (600 mg/ day) treatment at home and was clinically stable as confirmed by follow-up CSF analysis and MRI (Fig. 1D).

Six months later, CSF isolate was re-identified and cultured on canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) medium and the isolate was identified C. gattii sensu stricto. Molecular taxonomy via sequencing of the URA5 gene revealed that the isolate was genotype AFLP4/ VGI, representing the recently described C. gattii sensu stricto [2]. Antifungal susceptibility obtained by a commercially prepared, dried colorimetric microdilution panel (Sensititre YeastOne, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, West Sussex, UK) showed 0.5 mg/ mL for AmB, 8 mg/ mL for 5-FC, and 8 mg/ mL for FLC.

Discussion

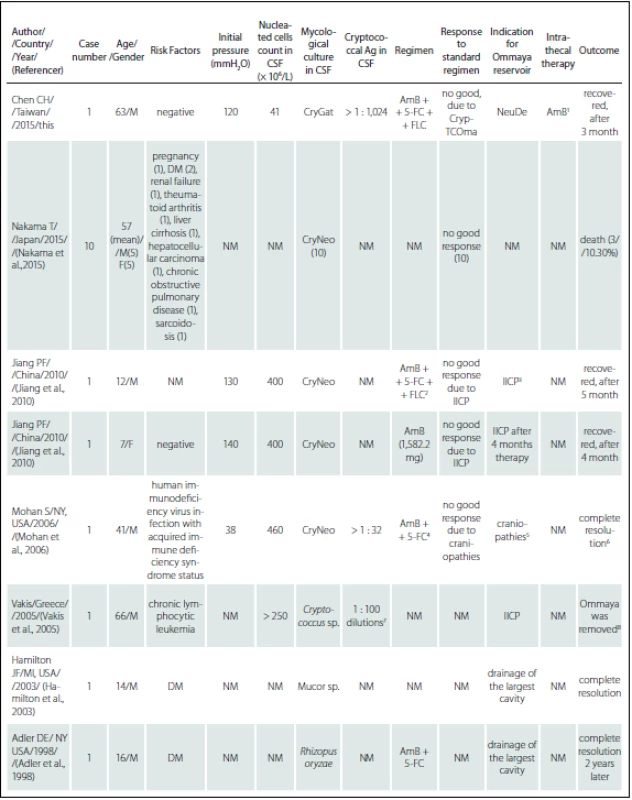

This is the first case report describing administration of adjunctive intra-ventricular amphotericin B via the Ommaya reservoir to treat neurological complications of C. gattii AFLP4/ VGI-induced CM. The present report demonstrated that adjunctive intra-ventricular AmB delivered via Ommaya reservoir could represent an alternative treatment for patients with C. gattii AFLP4/ VGI-induced CM who fail to respond adequately to conventional interventions. As intra-ventricular antifungal treatment via an Ommaya implant has been rarely utilized to treat CNS cryptococcosis, we conducted a literature review to support our course of treatment (summarized in Tab. 2). On analyzing the reports, we found that Ommaya reservoirs were frequently applied in the treatment of refractory CM, notably in immunocompromised or fragile populations. Considering the disease course characteristics and poor response from our patient, the few case studies describing treatment of CM with an Ommaya reservoir suggested a potential alternative treatment for our patient. Our intervention led to eradication of C. gattii sensu stricto and resolution of clinical manifestations. We believe that intraventricular administration of AmB in our patient enabled more of the drug to pass through the blood-brain barrier, resulting in higher brain concentrations than with the conventional approach. The intraventricular approach also yielded practical secondary benefits, since intracranial pressure could be directly monitored and simultaneously managed at high pressure, without any further adverse effects. Although intraventricular administration of antifungal agents and decompression of intracranial pressure through an Ommaya reservoir was not the standard approach, and was even discouraged in accordance with CM treatment guidelines, we believe this intervention could be reserved as a last resort for similar clinical cases. However, there are potential disadvantages of intraventricular antifungal injection via an Ommaya reservoir, including device-associated infections [15], over-drainage of the CSF [16], tentorial/ tonsillar herniation [17] and subdural hematoma [18].

2. References review of Ommaya reservoir in the management of cerebral fungal infection.

5-FC – flucytosine; Ag – antigen; AmB – Amphotericin B; CryGat – <i>Cryptococcus gattii</i>; CryNeo – <i>Cryptococcus neoformans</i>; CrypTCOma – Cryptococcoma; CSF – cerebrospinal fluid; DM – diabetes mellitus; F – female; FLC – fluconazole; IICP – increasing intracerebral pressure; M – male; NeuDe – neurological deterioration. Notes: <sup>1</sup> – AmB (0.25 mg/dose, 6 dose per week, intrathecal, in total 12 mg); <sup>2</sup> – AmB (from 0.2 to 1 mg/kg/day ), 5-5-FC (150 mg/kg/day ) and FLC (3 mg/kg/day); <sup>3</sup> – follow up opening pressure over 400 mmH<sub>2</sub>O, and the follow up brain CT scan showed increasing dilatation of lateral ventricles; <sup>4</sup> – AmB (50 mg/day) and 5-FC (6 gm/day ); <sup>5</sup> – IICP and complete loss of hearing and significant deterioration of vision as well as bilateral facial palsy and bilateral sixth nerve palsy; <sup>6</sup> – complete resolution of the sixth and seventh cranial nerve palsies bilaterally by the 65<sup>th</sup> day of hospital stay; <sup>7</sup> – positive after 1 : 100 on serial dilutions; <sup>8</sup> – Ommaya-type device was removed due to cerebral abscess, and V-P adjustable shunt (Hakim Programmable Valve, Godman) was placed 2 months later; <sup>9</sup> – positive after 1 : 30,000 on serial dilutions; <sup>10</sup> – died 3 months later after Ommaya reservoir due to a gastrointestinal haemorrhage. We emphasize that physicians should pay attention to the possible complications of cryptococcal infection in patients, even during active therapy. We also stress the importance of discriminating between C. gattii and C. neoformans, using CGB medium in clinical situations, as it is necessary to achieve a positive outcome. Immunocompetent individuals are also susceptible to CM infection.

In conclusion, intraventricular administration of antifungal agents via an Ommaya reservoir could represent an alternative choice for treating patients with C. gattii AFLP4/ VGI-induced CM, who respond inadequately to typical interventions. However, we recommend that it should only be used after attempting all other treatment options.

All acknowledgements

The authors thank the Changhua Christian Hospital for the grant support (CCH grant 104-CCH-IRP-001, CCH grant 105-CCH-IRP-001). All authors thank the assistant of the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Changhua Christian Hospital for their assistance in data collection. Authors thank Miss Yi-Chen Tseng and Miss Chi-Lun Chang, who study at Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Biopharmaceuticals, National Chiayi University, Chiayi City, for the re-identification of the isolate. This research project would not have been possible without the support of many people. The authors wish to express our gratitude to staffs of Division of Infectious Diseases, Division of Neurosurgery, and Division of Critical Care of Changhua Christian Hospital who were abundantly helpful and offered patient care, invaluable assistance, and support.

Chen Chang-Hua, MD

Division of Infectious Diseases

Department of Internal Medicine

Changhua Christian Hospital

135 Nanhsiao Street

Changhua 500

Taiwan

e-mail: 76590@cch.org.tw

Accepted for review: 25. 8. 2016

Accepted for print: 2. 1. 2017

Sources

1. Hagen F, Khayhan K, Theelen B, et al. Recognition of seven species in the Cryptococcus gattii/ Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Fungal Genet Biol 2015;78 : 16 – 48. doi: 10.1016/ j.fgb.2015.02.009.

2. Hagen F, Hare Jensen R, Meis JF, et al. Molecular epidemiology and in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of 108 clinical Cryptococcus neoformans sensu lato and Cryptococcus gattii sensu lato isolates from Denmark. Mycoses 2016;59(9):576 – 84. doi: 10.1111/ myc.12507.

3. Chen CH, Sy HN, Lin LJ, et al. Epidemiological characterization and prognostic factors in patients with confirmed cerebral cryptococcosis in central Taiwan. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2015;21 : 12. doi: 10.1186/ s40409-015-0012-0.

4. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50(3):291 – 322. doi: 10.1086/ 649858.

5. Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014;27(4):980 – 1024. doi: 10.1128/ CMR.00126-13.

6. Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Sondermeyer G, et al. Cryptococcus gattii infections in multiple states outside the US Pacific Northwest. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19(10):1620 – 6. doi: 10.3201/ eid1910.130441.

7. Del Poeta M, Casadevall A. Ten challenges on cryptococcus and cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia 2012;173(5 – 6):303 – 10. doi: 10.1007/ s11046-011-9473-z.

8. Tseng HK, Liu CP, Ho MW, et al. Microbiological, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with cryptococcosis in Taiwan, 1997 – 2010. PLoS One 2013;8(4):e61921. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0061921.

9. Hay RJ, Mackenzie DW, Campbell CK, et al. Cryp-tococcosis in the United Kingdom and the Irish Republic: an analysis of 69 cases. J Infect 1980;2(1):13 – 22.

10. Harris J, Lockhart S, Chiller T. Cryptococcus gattii: where do we go from here? Med Mycol 2012;50(2):113 – 29. doi: 10.3109/ 13693786.2011.607854.

11. Ngamskulrungroj P, Chang Y, Sionov E, et al. The primary target organ of Cryptococcus gattii is different from that of Cryptococcus neoformans in a murine model. M Bio 2012;3(3):e00103-12. doi: 10.1128/ mBio.00103-12.

12. Yuchong C, Fubin C, Jianghan C, et al. Cryptococcosis in China (1985 – 2010): review of cases from Chinese database. Mycopathologia 2012;173(5 – 6):329 – 35. doi: 10.1007/ s11046-011-9471-1.

13. Abassi M, Boulware DR, Rhein J. Cryptococcal Meningitis: Diagnosis and Management Update. Curr Trop Med Rep 2015;2(2):90 – 9.

14. Goudas LC, Langlade A, Serrie A et al. Acute decreases in cerebrospinal fluid glutathione levels after intracerebroventricular morphine for cancer pain. Anesth Analg 1999;89(5):1209 – 15.

15. Diamond RD, Bennett JE. A subcutaneous reservoir for intrathecal therapy of fungal meningitis. N Engl J Med 1973;288(4):186 – 8.

16. Samadani U, Huang JH, Baranov D, et al. Intracranial hypotension after intraoperative lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Neurosurgery 2003;52(1):148 – 51.

17. Dagnew E, van Loveren HR, Tew JM Jr. Acute foramen magnum syndrome caused by an acquired Chiari malformation after lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid: report of three cases. Neurosurgery 2002;51(3):823 – 8.

18. Dardik A, Perler BA, Roseborough GS, et al. Subdural hematoma after thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: an underreported complication of spinal fluid drainage? J Vasc Surg 2002;36(1):47 – 50.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery Neurology

Article was published inCzech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2017 Issue 3-

All articles in this issue

- Low Back Pain – Evidence-based Medicine and Current Clinical Practice. Is there Any Reason to Change Anything?

- Results of Endocrine Function after Transsphenoidal Surgery for Non-functional Pituitary Macroadenomas

- Radiological Findings in Term-neonates with Hypoxic-ischemic Encephalopathy

- Token Test – Validation Study in Older Czech Adults and Patients with Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Measurement of Malingering – Coin in the Hand Test

- Effects of Targeted Orofacial Rehabilitation in Patients after Stroke with Speech Disorders

- Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Patients with Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Anti-NMDAR Antibodies in Demyelinating Diseases

- Pyridoxine-dependent Epilepsy – Case Reports

- Classification of Central Nervous System Tumors – WHO 2016 Update

- Quality of Life in Self-sufficient Patients after Stroke

- Myotonic Dystrophy – Unity in Diversity

- Febrile Seizures – Sometimes Less is More

- Fetal Radiation Risk Due to X-ray Procedures Performed on Pregnant Women

- Successful Treatment of Meningoencephalitis due to Cryptococcus gattii with Ommaya Reservoir and Intrathecal Injection of Amphotericin B – a Case Report

- Differential Diagnosis of Bithalamic and Pallidal Hypointensity – a Case of HEXB Mutation

- Significant Brain Oedema in Unruptured Brain Arteriovenous Malformation – a Case Report

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Myotonic Dystrophy – Unity in Diversity

- Fetal Radiation Risk Due to X-ray Procedures Performed on Pregnant Women

- Low Back Pain – Evidence-based Medicine and Current Clinical Practice. Is there Any Reason to Change Anything?

- Febrile Seizures – Sometimes Less is More

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career