-

Medical journals

- Career

The Chest Wall Tumor as a Rare Clinical Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis

Authors: S. Porsok 1; M. Mego 1; D. Pinďák 2; R. Duchoň 2; J. Beniak 3; J. Mardiak 1

Authors‘ workplace: Department of Medical Oncology School of Medicine, Comenius University, National Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 1; Department of Oncological Surgery, Slovak Medical University, National Cancer Institute, Bratislava, Slovak Republic 2; POKO Poprad, s. r. o., Slovak Republic 3

Published in: Klin Onkol 2017; 30(4): 299-301

Category: Case Report

doi: https://doi.org/10.14735/amko2017299Overview

Background:

Extrahepatic metastatic spread of hepatocellular carcinoma is present at the time of diagnosis in 5–15% of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. The most common site of metastastic spread is the lungs, bones, lymph nodes. Isolated chest wall localization is extremely rare.Case:

We report a 58-year-old patient with large, synchronous chest wall hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis with solitary primary hepatocellular carcinoma. He underwent a radical, surgical en bloc metastasectomy and subsequent anatomic liver resection. Removal of this metastasis further led to aggressive dissemination to different sites during the course of the disease and subsequently the patient was treated with antiangiogenic therapy and, after failure, with systemic chemotherapy. Combined multimodality treatment in this case led to overall survival of 22-months. We suggest that the initial huge presentation of chest wall metastasis and consecutive aggressive dissemination after surgical removal could be explained by the biological process called “tumor self-seeding” by circulating tumor cells.Conclusion:

The chest wall hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis is a rare entity associated with poor prognosis. Radical surgical approach is limited to a minority of patients and may be justified for the treatment of extrahepatic metastases on a case by case basis.Key words:

hepatocellular carcinoma – chest wall metastasis – metastasectomy – ciculating tumor cellsIntroduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common neoplasm and the third most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. The incidence varies from 3 out of 100 000 in Western countries, to more than 15 out of 100 000 in certain areas of the world, mapping the geographical distribution of viral hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) [1]. In the majority of patients, a localized or locally advanced disease is present. Herein, we report a rare case of HCC with initial presentation of solitary chest wall metastasis.

Case report

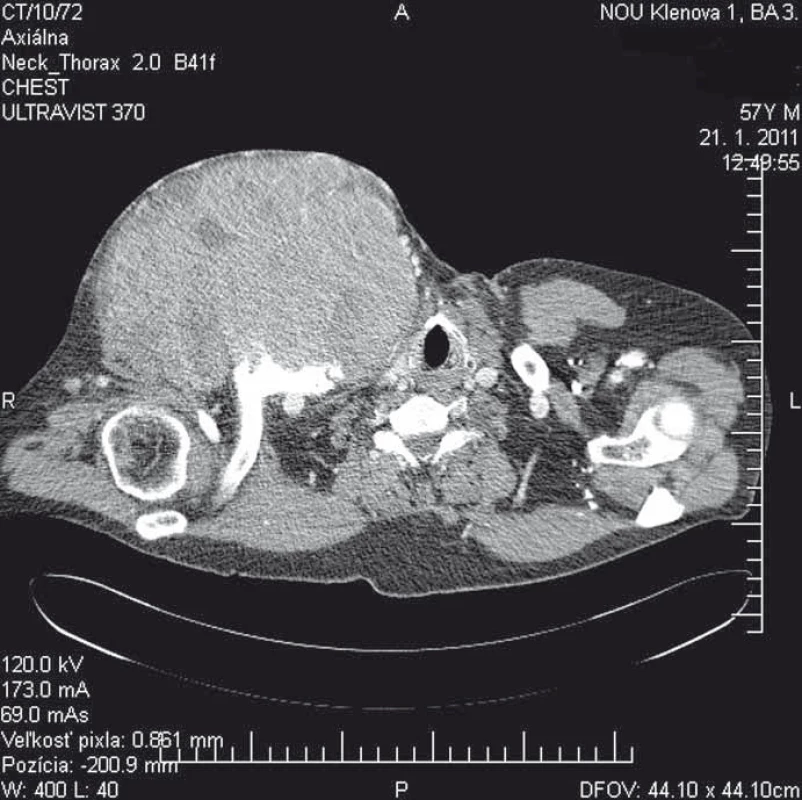

We report a 58-year-old patient who, in December 2010, visited an oncologist with a 5-month rapidly growing tumor lesion in the right upper chest wall region. The physical findings presented a large tumor, approximately 15 × 20 cm in size (Fig. 1). A staging thorax and abdomen computed tomography (CT) scan verified a large encapsulated tumor 17 × 11 × 13 cm (Fig. 2), localized in the right subclavicular region, with suspected infiltration of clavicula, chest wall, tumor lesion in the right hepatic lobe S6, without typical radiological characterization of HCC, 3 cm in diameter. A biopsy of the chest wall tumor verified a metastatic spread of HCC, G1. Laboratory screening was completely negative in relationship to HBV, HCV, AFP, leukocytosis, normal blood coagulation and biochemical values.

1. The physical findings presented a large tumor, approximately 15 × 20 cm in size.

2. A staging thorax and abdomen CT scan verified a large encapsulated tumor 17 × 11 × 13 cm.

The patient was presented to a multidisciplinary tumor board with the decision of resectability of the chest wall tumor, due to the bordered tumor, assumption of radical resection and limited cervico-brachial mobility. In February 2011, the tumor was surgically completely removed with partial resection of the clavicula and transposition of the major pectoral muscle. Definitive histology confirmed a metastatic spread of HCC, R0 resection. A segmentectomy was performed in March 2011, and histology confirmed HCC, R0 resection.

Until September 2011, the patient was observed. In October 2011, the patient’s performance status declined, and he experienced worsening abdominal and back pain. A control CT scan verified a metastatic dissemination to the lung, lumbosacral spine and locoregional relapse to the chest wall. The patient started with palliative therapy of Sorafenib 400 mg bid, intravenous zoledronic acid once every 4 weeks. Because of bad toleration of Sorafenib, hand and foot syndrome G2, stomatitis, anorexia and loss of appetite, the dose of Sorafenib was reduced to 200 mg bid. Local external radiotherapy was applied to the lumbosacral spine in a total dose of 20 Gy. In December 2011, new neurological symptoms, headache, and double vision occurred. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a metastatic dissemination to the skull and left orbital cavity, with oppression of optic nerves and vessels. Due to the close localization of the tumor to optic vessels and nerves, external radiotherapy was not applied. Systemic Sorafenib therapy was stopped, and treatment was continued on the basis of best supportive care. After improvement of the performance status, in February 2012, the patient started 2nd line systemic therapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin. The therapy was continued until May 2012. In June 2012 the control CT scan verified a progression of metastatic lesion in the lung, liver, bones, cervical lymph nodes. Systemic therapy was stopped, and the patient was treated with best supportive care. Despite this treatment, the patient’s clinical status deteriorated rapidly, and the patient died in August 2012.

Discussion

Extrahepatic metastatic spread is present at the time of diagnosis in only approximately 5–15% of cases [2,3]. Metastases are more common in patients with advanced primary tumors (> 5 cm, large vessel vascular invasion). The most common sites of metastatic spread are the lungs (45–50%), bones (35–40%), intra-abdominal lymph nodes (45%) and adrenal gland (12%) [4–6]. Brain metastases are rare overall (0.2–2% of cases), more common in advanced stage disease [7]. Chest wall metastases are extremely rare. Only a few cases, including synchronous primary liver and unknown primary site HCC chest wall metastases [8–10], have been published.

Our patient was initially presented with a stage IV disease, however, with only a solitary chest wall metastasis. Removal of this metastasis further led to dissemination to different sites during the course of the disease. This case is interesting from a biological as well as from a clinical point of view. Solitary chest wall metastasis is an unusual presentation of HCC. We suggest that initial presentation of solitary, huge metastasis in relation to a relatively small primary could be explained by the biological process called tumor self-seeding by circulating tumor cells (CTC). Tumor self-seeding by CTC describes the multidirectional capacity of cancer cells to seed distant organs as well as self-seeding of the primary tumor, while tumor-derived inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL-6) a interleukin 8 (IL-8) act as CTC attractants, promoting accelerated tumor growth, angiogenesis, and recruitment of myeloid cells into the stroma [11]. We suggest that in this case, the huge solitary chest wall metastasis works as a CTC trap, where CTC were attracted by chemokines in the process of self-seeding. While this process leads to progression of this metastasis, at the same time, it probably prevents CTC dissemination to different sites. We speculate that removal of this metastasis abrogates self-seeding and allows CTCs to disseminate.

The standard treatment of stage IV HCC is Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic and antiproliferative effect or best supportive care according to performance status and liver metabolic status expressed as Child-Pugh score. Surgical resection of extrahepatic metastases reported a limited benefit and only rarely is associated with long-term survival. Limited pulmonary metastasis resection, with a 5-year survival rate of 27–33% after resection has the most favorable prognosis [12–14].

The outcomes of surgical resection of extrahepatic metastases including in the lung, bone, brain, soft tissues, adrenal glands, heart showed poorer prognosis than in the lung and are associated with the dismal prognosis. The reported 3-year survival rate was 0–9% [15].

In our case, synchronous surgical removal of primary HCC and chest wall metastasis led to progression-free survival of 6 months, while overall survival was 22 months. The clinical effect and toxicity profile of Sorafenib treatment in our case was comparable with published SHARP and Asia-Pacific Data, while the effect of chemotherapy is limited as shown in our case as well.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the synchronous extrahepatic chest wall HCC metastasis reported in our case report is a rare entity associated with poor prognosis. Adequate therapeutic options are still being debated. Radical surgical approach is limited to a minority of patients based on resectability of the tumor and surgical experience. In case of unresectable disease, the therapeutic options include systemic antiangiogenic therapy, immunotherapy, chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. Until other treatment approaches are established to improve life expectancy and the patient’s quality of life, surgical resection may be justified for the treatment of extrahepatic metastases on case by case basis.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE recommendation for biomedical papers.

Stefan Porsok, MD

Department of Medical Oncology

School of Medicine

Comenius University

National Cancer Institute

Klenova 1

831 02 Bratislava

Slovak Republic

e-mail: stefpors@gmail.com

Submitted: 12. 3. 2017

Accepted: 20. 4. 2017

Sources

1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005; 55 (2): 74–108.

2. Uka K, Aikata H, Takaki S et al. Clinical features and prognosis of patients with extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13 (3): 414–420.

3. Katyal S, Oliver JH 3rd, Peterson MS. Extrahepatic metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology 2000; 216 (3): 698–703.

4. Yoon KT, Kim JK, Kim DY et al. Role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in detecting extrahepatic metastasis in pretreatment staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2007; 72 (Suppl 1): 104–110.

5. Yuki K, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M et al. Growth and spread of hepatocellular carcinoma. A review of 240 consecutive autopsy cases. Cancer 1990; 66 (10): 2174–2179.

6. Yi J, Gwak GY, Sinn DH et al. Screening for extrahepatic metastases by additional staging modalities is required for hepatocellular carcinoma patients beyond modified UICC stage T1. Hepatogastroenterology 2013; 60 (122): 328–332.

7. Choi HJ, Cho BC, Sohn JH et al. Brain metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic factors and outcome: brain metastasis from HCC. J Neurooncol 2009; 91 (3): 307–313. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9713-3.

8. Coban S, Yüksel O, Köklü S et al. A typical presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma: a mass on the left thoracic wall. BMC Cancer 2004; 4 : 89.

9. Knippig C, Röcken C, Roessner A et al. Shoulder metastasis as the initial manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Med Klin (Munich) 2002; 97 (6): 361–364.

10. Hyun YS, Choi HS, Bae JH et al. Chest wall metastasis from unknown primary site of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12 (13): 2139–2142.

11. Kim MY, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S et al. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell 2009; 139 (7): 1315–1326.

12. Chan KM, Yu MC, Wu TJ et al. Efficacy of surgical resection in management of isolated extrahepatic metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15 (43): 5481–5488.

13. Tomimaru Y, Sasaki Y, Yamada T et al. The significance of surgical resection for pulmonary metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg 2006; 192 (1): 46–51.

14. Kuo SW, Chang YL, Huang PM et al. Prognostic factors for pulmonary metastasectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14 (2): 992–997.

15. Kawamura M, Nakajima J, Matsuguma H et al. Surgical outcomes for pulmonary metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg 2008; 34 (1): 196–199.

Labels

Paediatric clinical oncology Surgery Clinical oncology

Article was published inClinical Oncology

2017 Issue 4-

All articles in this issue

- Novel Findings in Follicular Lymphoma Pathogenesis and the Concepts of Targeted Therapy

- Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy in the Diagnostics of Malignancy of the Gastrointestinal Tract

- Radiation Necrosis in the Upper Cervical Spinal Cord in a Patient Treated with Proton Therapy after Radical Resection of the Fourth Ventricle Ependymoma

- Metastatic Pituitary Disorders

- Intensity Modulated Hyperfractionated Accelerated Radiotherapy to Treat Advanced Head and Neck Cancer – Predictive Factors of Overall Survival

- Docetaxel–Cabazitaxel–Enzalutamide Versus Docetaxel–Enzalutamide in Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer

- Reactive Lymphoid Hyperplasia of the Liver

- Radiotherapy of Lung Tumours in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- The Chest Wall Tumor as a Rare Clinical Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis

- Clinical Oncology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- Online only

- About the journal

Most read in this issue- Metastatic Pituitary Disorders

- Reactive Lymphoid Hyperplasia of the Liver

- Radiotherapy of Lung Tumours in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Radiation Necrosis in the Upper Cervical Spinal Cord in a Patient Treated with Proton Therapy after Radical Resection of the Fourth Ventricle Ependymoma

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career