-

Medical journals

- Career

Singlehood among Adults with Intellectual Disability: Psychological and Sociological Perspectives

Authors: Hefziba Vahav 1*; Hagit Hagoel 2; Fridle Sara 3

Authors‘ workplace: Ph. D. student at the School of Education, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel ; Statistical counselor, Lecturer at the School of Education, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel ; Associate Professor, Head of ID Majoring Program, Special Education Department, School of Education, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel

Published in: Acta Psychopathologica, 1, 2015, č. 2:12, s. 1-18

Related article at Pubmed, Scholar Google

Visit for more related articles at Acta Psychopathologica

© Under License of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

This article is available from: www.psychopathology.imedpub.comOverview

This study aims to examine the phenomenon of singlehood among adults with intellectual disability (ID), using psychological (attachment and intimacy theories) and sociological theories (the selective/adaptation mechanisms) that explain singlehood in the general population. The sample included 56 couples and 40 singles with mild/moderate ID (CA: M = 37.54, SD = 10.90), who responded to a singlehood battery of 10 questionnaires. Contrary to our hypothesis, no differences were found between singles and couples with ID in attachment, intimacy and social emotional skills. However, significant differences were found in attachment to a close figure and in expectations from marriage and a partner, indicating that the singles have unrealistic marriage schemata. All participants expressed a desire to have an intimate relationship and marry. Does society ignore these needs?

Keywords:

Singlehood; Adults with intellectual disability; Psychologic; Sociological perspectiveIntroduction

In modern societies, marriage is considered a cultural universal. Nearly 90% of the world’s adults aged 45-49 have been married at least once (Goodwin and Mosher, 2010) [1]. Parallel to these trends, an increase in single-person households is being seen around the world (Poortman and Liefbroer, 2010) [2]. Nevertheless, marriage is still perceived as more respectable. Singlehood suffers from stigma and prejudice (Budgeon, 2008); Singles are perceived as outsiders who lack maturity (Lahad, 2012) [3]. Conversely, most persons with intellectual disability (ID) are single (Brown, 1996) [4]. In Israel, for example, only 10% of adults with ID are married, and another 20% are in heterosexual relationships (Israel Welfare Ministry, Division of Persons with ID, 2014).

Historically, there has been resistance to people with ID being in couple relationships, living together or marrying due to fear of their ability to take responsibility or raise children (Munero, 2013) [5]. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) states: “States Parties shall take effective and appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against persons with disabilities in all matters relating to marriage, family, parenthood and relationships” (page 19). Consistent with this mandate, the discourse of sexual expression, love and marriage for people with ID has become more open in society (Aparecida, 2009).

Studies of populations with ID have focused mainly on their right and ability to form romantic relationships, love and have intimate relationships (May and Simpson, 2003) [6]. Similar to the general population, it was found that partnership and marriage increase the social and personal growth of persons with ID (Brown, 1996), and contribute to their well-being and quality of life (Arias et al., 2009; Löfgren-Mårtenson, 2004; Reiter and Neuman, 2013; Weinberger, 2007) [7,8].

Despite these findings, families and staff exhibit conservative attitudes towards sex, love, marriage and parenthood of adults with ID (Tsutsumi, 2009; Young, Gore and McCarthy, 2012) [9,10]. Due to difficulties with basic social and emotional skills that stem from their ID, persons with ID are considered naïve people who have not and will not grow up, remaining too immature for partnership, marriage and especially parenthood (Bogdan and Taylor, 1994; O’Brien and O’Brien , 1993; Wolfe, 1997) [11-13]. The initiative for studying singlehood came from parents of adults with ID who want to see their offspring married (or at least in a partnership), and were eager to explore their persistent singlehood. Partnership is traditionally defined as involvement in a monogamous relationship for at least two years (Lahad, 2012) [3]. Singlehood refers to persons who have never been engaged in a committed long-term relationship (excluding single mothers, widows or divorced persons).

In the general population, singlehood is explained by psychological and sociological paradigms. The psychological paradigm attributes singlehood to the individual and his relationships with family members using the attachment theory (Bowlby, 1973, 1988; Hazan & Shaver, 1987) [14-16] and intimacy theory, which is part of Erikson’s (1963) psycho-social stages theory). The sociological paradigm views singlehood in a broader context – the interrelationship between the individual and society – and uses, inter alia, selective-adaptation mechanisms (Liefbroer, 1998; Poortman & Liefbroer, 2012) [2,17] to explain the phenomena. A dearth of singlehood theories for adults with ID led us to advocate using the above theories in a population with ID. However, we were interested to clarify if the claim (O’Brien & O’Brien) that singlehood in a population with ID stems from the social-emotional barriers inherent to intellectual disability itself is supported or based on prejudice.

Singlehood according to Psychological Theories Attachment theory

(Bowlby, 1973, 1988; Hazan and Shaver, 1987) [14-16] Mikulincer and Shaver (2011) [18], present three “attachment styles” in the realm of romantic love: Avoidance, which reflects distrust of partners, and a striving for independence and emotional distance; Anxiety, which reflects concern about being abandoned and rejected; and Security which reflects a more satisfied and committed relationship. Schachner, Shaver and Gillath (2008) [19] found that singles report negative childhood experiences with parents, and exhibit an avoidant or anxious attachment style.

Another aspect of singlehood is the attachment hierarchy of single and married people to close figures. Trinke and Bartholomew (1997) found that singles (aged 17-45) positioned relationships with mothers before other figures, whereas couples positioned fathers and friends before others. Since individuals with ID have been documented as being more attached to their mothers (Glidden et al., 2006) [20], we examined whether differences in attachment style and hierarchy would be found between singles and couples with ID.

Psycho-social theory

(Erikson, 1963) [21] Intimacy versus isolation is the sixth stage of Erikson’s psycho-social development theory (ages 19-40). Intimacy is defined as a positive emotional bond that includes understanding and support, warmth, connectedness, and caring (Seligman and Shanok, 1996) [22]. A poor sense of self leads to less committed relationships, emotional isolation, loneliness, and depression (Shulman, 1993) [23]. Levels of intimacy among singles with ID and couples were examined.

Sociological perspective

Liefbroer (1998) [17] and Poortman and Liefbroer (2010) [2] view singlehood in a sociological context conveyed, consciously and unconsciously, by the societal values that a person absorbs from social agents, including key figures in their immediate environment, such as parents, friends, caregivers and staff (for a population with ID). Mass media also serves as social agent from whom people learn about socialization, love, intimate romance and similar subjects.

They suggest two mechanisms for explaining singlehood in modern society: The selective mechanism postulates that persons with pro-family values and realistic expectations from marriage and partner are selected into marriage, whereas those with more individualized values and high expectations from marriage and partner remain single. These values convey that being single is a choice. The adaptation mechanism postulates that attitudes towards couplehood and marriage are a result, rather than a cause, of the differences in a person’s status; singlehood stems from lack of chance.

In line with Poortman and Liefbroer (2012) [2], we drew the selection/adaptation mechanisms into our study in two steps: (a) exploring the desire of participants with ID to have partners and marry, which might clarify whether singlehood in this population stem from individual choice, (b) examining participants’ expectations from marriage and partners, which might reflect their values and thoughts about these issues, and clarify if singlehood is caused by a lack of chance.

Social/Emotional Barriers of Persons with ID

It is documented that individuals with ID exhibit difficulties with the basic communications and social skills needed to form samesex friendships and are considered an “unlikely alliance” (O’Brien and O’Brien, 1993). They exhibit low self-esteem, low tolerance for frustration, and difficulties with problem-solving (Heiman and Margalit, 1998; Margalit, 1996) [24], which increase their loneliness and isolation. We examined whether differences in basic social skills would be found between singles with ID and those in couples.

Intimacy and Gender Differences

Different patterns of intimacy have been found in men and women (Duck and Wood 2006; Heller and Wood, 1998; Hook, Gerstein, and Gridley, 2003) [25]. Men are goal-oriented and instrumental. Their intimacy style is more active and less verbal, and includes shared leisure and practical help. Women are emotion-oriented, and their intimacy style includes fraternity and friendship. However, Shachar and Sharon (2010) [26] found no gender differences in the motivations for and expectations from marriage. We asked whether gender differences would be found for any or all of the questionnaires.

In conclusion, we use a triadic model to elucidate the singlehood phenomenon among adults with ID. The first dimension relate to basic social-emotional barriers due to ID; the second one to psychological theories (attachment and intimacy) and the third one to sociological theories (selective/adaptation mechanisms). We compared two groups: adults with ID who are married or in long-term, heterosexual relationships to singles with ID. Our operative goals were to examine differences between singles and couples with ID in (a) basic social-emotional skills (b) attachment style and attachment hierarchy to close figures; (c) level of intimacy; (d) expectations from marriage and partner; (d). We hypothesized that couples with ID would exhibit a higher level of social-emotional skill, a more secure attachment style (Schachner et al., 2008) [19], a higher level of intimacy (Shulman, 1993) [23] and more realistic expectations from marriage and partners than singles with ID. Due to a dearth of research on gender differences in these issues in populations with ID, we preferred to posit a question: Will there be gender differences on any or all of the research questionnaires, beyond status (singles/couplehood)?

Method

Participants

The sample included 96 adults with ID, divided into couples (58%; n = 56) and singles (42%; n = 40). Couples were defined as those who are married or in a relationship for at least two years. Singles were defined as never having been in a relationship that lasted at least two years. This sample size is acceptable in studies of special education populations, and for populations with ID and autism (Bauminger-Zviely and Agam-Ben-Artzi, 2014; Tzuriel and Hanuka-Levy, 2015) [27,28].

Chronological age: The age range was 25-65 (M = 37.54, SD = 10.90), with no significant difference in age between singles and couples (t = 1.41; p > .05).

Gender: The singles group was comprised of 45% (n = 18) women and 55% men (n = 22), whereas the couples group was comprised of 64% women (n = 36) and 36% (n = 20) men. There was no significant difference in the number of men and women in the singles and couples groups [χ2 (df/1) = 3.53; p > .05].

IQ: The mean IQ according to the traditional AAMR definition (Grossman, 1983) was 50-70 (MIQ = 59.65), with no significant difference between singles and those in couplehood (t = -1.03, p > .05). Data on IQ were drawn from the participants’ personal files.

Mental age: The mean mental age (PPVT , Dunn and Dunn, 1997) was 6.95 (SD = 1.95), with no significant difference between the groups (t = -1.15, p > .05).

Etiology: Sixty-eight of the participants had nonspecific ID (70.8%), and 28 (29.2%) had Down syndrome, with no significant difference between the groups [X (df/1) = 1.44; p > .05].

Residence: All participants live in community residences such as hostels (40 or more residents) and apartments (5-6 residents) that are under the supervision of the Division of Intellectual Disability in the Israel Welfare Ministry. There was no significant difference in the number of singles and couples [X (df/1) = 3.53; p > .05] in each type of residence. In the morning, participants work in vocational centers or the open market, and participate in leisure activities in the afternoons.

Research Questionnaires

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Scale (Dunn and Dunn, 1997) [29] was administered to match between singles and couples. This test has been correlated with general intelligence and is commonly used in populations with ID (α = .93).

Singlehood battery: The battery was divided to three dimensions according to the triadic model that served as the basis of this study. Each dimension was the subject of 2-4 questionnaires. Singlehood in the general population is examined using quantitative questionnaires and qualitative, deep interviews with the singles themselves. The latter are based on narratives that require rich, expressive language. Due to barriers in expressive language of individuals with ID with and without Down syndrome (Bellugi and Wang, 1998) [30], we preferred the quantitative research methods that do not rely on high verbal levels.

There are three main problems that might arise from using selfreport questionnaires in a population with ID (Finlay and Lyons, 2001; Tsoi, Chen, Zhang and Wang, 2013) [31]: content (e.g., quantitative judgments, generalizations), question phrasing (e.g., modifiers), format of the response (e.g., acquiescence, multiplechoice questions). In line with Tsoi et al., we took several steps to overcome these barriers: We shortened the questionnaires, simplified the language according to easy-to-read principles (Miller and Burstow, 2010) [32], excluded negative questions, and did not ask the same question twice (reversed), and reduced all the scales to three points.

Difficulties with basic social/emotional skills: Three questionnaires were used to examine whether singlehood in a population with ID stem from difficulties with basic social/ emotional skills inherited in the ID itself.

Self-concept was measured using the Israeli Hebrew “I am/He is,” questionnaire (Glanz, 1989; validated for individuals with developmental disabilities, Lifshitz et al., 2007 α = .80) [33,34]. This questionnaire was preferred because it has fewer items (38) and a three-point scale. We used the 10 personal self-concept items (i.e., “He is a good person,” α = .83). Participants are presented with a figure that serves as a model and are asked to evaluate themselves compared to a statement attributed to this figure. Explorative factor analysis yielded two factors (subscales) explaining 52.83% of the EPV. “External traits” (“He is nice looking”) contributed 27.85% and “personality traits” (“He is smart’) contributed 24.96% of the EPV (α = .82 and .81, respectively). Scoring in each subscale ranged between 1-low self-esteem and 3-high self-esteem.

The Friendship Quality Questionnaire

(Parker and Asher, 1993; Hebrew: Margalit, 1996) [35,24] examines the quality of friendship of adolescents and adults. Heiman (2000) validated it in a population with ID. Confirmative factor analysis yielded three factors explaining 56.73% of the EPV. “Support and esteem” contributed 23.55%, “conflicts and making up” 14.14% and “shared leisure” 19.03% of the EPV (α = .60, .72 and .71, respectively). Scoring in each subscale ranged between 1-disagree and 3-agree.

The Fundamental Interpersonal Orientation Behavior Questionnaire (FIRO-B)

(Schutz, 1978; 1994; Hebrew, Efrati, 2001) [36-38] aimed to examine interpersonal relationships. Schutz (1978, 1994) [36,37] posits three dimensions as necessary in human interpersonal relationships: inclusion, control and affection, and differentiates between expressed and desired behavior in each dimension. Stable and supportive interpersonal relationships can serve as protective factors against psychological stress and illness. Confirmative factor analysis yielded four factors explaining 59.38% of the EPV. “Expressed affect” contributed 15.49%, “desired affect” contributed 14.68%, “expressed control” contributed 14.61% and “desired control” contributed 14.59% of the EPV (α = .62, .60, .60 and .63, respectively). Scoring of the four subscales: 1-never and 3-always.

Singlehood According to Psychological Theories

We used two questionnaires related to attachment style and two intimacy questionnaires. The Attachment style questionnaire (Hazan and Shaver, 1987, Hebrew: Tolmenz, 1988) [16,39] has nine items that examine adults’ three attachment style (α = .63, .72 and .69 for the secure, avoidant and anxious styles, respectively). Larson, Alim, and Tsakanikos (2011) [40] used this questionnaire and found it suitable for populations with ID. Scoring of the three subscales range between: 1-not related to me, 3-related to me. The Network Relationships Inventory (NRI) (Furman and Buhrmester, 1985; Hebrew: Shulman, 1993) [23,41] examines a broad array of relationship characteristics with close figures: mother, father, friend, staff (because the participants live in community residences). It assesses five positive features, including companionship, disclosure, emotional support, approval, and satisfaction (α = .84, .84, .87 and .84 for closeness to the mother, father, friend, and staff, respectively). This questionnaire was not examined in a population with ID. However, a similar type of questionnaire was used by Heller, Miller, Hsieh and Stern (2000) [42] among adults with mild and moderate ID. Scoring of the three subscales ranged between 1-not at all and 3-very much.

The Fear of Intimacy Scale (FIS): (Descutner and Thelen, 1991) [43] examines an individual’s inhibited capacity to share personal thoughts and feelings with close figures. Two factors explained 53.9% of the variance (EPV): Active intimacy, 28.1%, and verbal intimacy 25.8% of the EPV (α = .74, .74 .81 for active intimacy, verbal intimacy and the entire questionnaire, respectively). Scoring of the two subscales ranged between 1-difficult for me and 3-not difficult for me at all.

The Adolescent Intimacy Questionnaire : (Shulman et al., 1997 in Hebrew) [44] examines intimacy with same-sex friends (8 items). Two factors explained 56.0% of the EPV: “Personal intimacy” (sharing personal thoughts with the friend) 37.34%, and “intimacy with others” (sharing thoughts related to the friend) 18.66% of the EPV (α = .82, .65 and .82 for personal intimacy, intimacy with others and the entire questionnaire, respectively). Scoring ranged between 1-not at all and 3-very much.

Singlehood according to Sociological Perspective

The values of participants, their expectations from marriage and partner (according to selective/adaptation mechanism approach) were examined using two questions on two questionnaires. Desire to have a partner and get married: Participants were asked two yes/no questions: (a) whether they wished to have a steady, heterosexual partner and (b) whether they wished to marry.

The Expectations from Marriage Scale (RMS): (Vilchinsky, 2004) [45] examines expectations from marriage. Two factors explained 52.34% of the variance: “Emotional expectations” (“someone to love you”) 27.11%, and “practical expectations” (“someone to help you”) 25.23% of the EPV (α = .80, .83 and .86 for emotional expectations, practical expectations and the entire questionnaire, respectively). Scoring of the two subscales ranged between 1-disagree and 3-agree.

The Preferred Traits in a Partner Questionnaire: (Shahar and Sharon, 2010) [26] examines expectations from partners/ spouses. Two factors explained 65.22% of the EPV: “Practical traits” (considerate, understanding) 36.9%, and “social and personal traits” (smart, sense of humor) 29.32% of the EPV (α = .81, .82 and .85 for practical traits, social and personal traits and the entire questionnaire, respectively). Scoring of the two subscales ranged between 1-disagree and 3-agree.

For the singlehood battery, there are three main problems that might arise from using self-report questionnaires in a population with ID (Finlay and Lyons, 2001; Tsoi, Chen, Zhang and Wang, 2013) [31]: content (e.g., quantitative judgments, generalizations), question phrasing (e.g., modifiers), format of the response (e.g., acquiescence, multiple-choice questions). In line with Tsoi et al., we took several steps to overcome these barriers: We shortened the questionnaires, simplified the language according to easy-toread principles (Miller and Burstow, 2010) [32], excluded negative questions, did not ask the same question twice (reversed), and reduced the scale to three points.

Procedure

Consent for participation was obtained from parents/guardians. Authorizations were obtained from the Division of Individuals with ID in the Welfare Ministry and the University Ethics Committee [46]. The study’s aim and procedure were explained to all participants. They signed an informed consent form for participation in scientific research (adapted to populations with ID). They were told that they could withdraw mid-study. According to the “normalization” principle (Wolfensberger, 2002) [47], the participants received payment or a gift for participating.

The battery was administered by the second author who is an educational counselor in the field of ID, in a private room in the vocational and residential facilities of the participants. In order to prevent fatigue and attention problems, the battery was administered in two sessions. In the first session, which lasted two hours with a 15-minutes break in the middle, the PPVT (Dunn and Dunn, 1997) [29] was administered, followed by the singlehood battery. The second session was scheduled by the interviewer and participant, a few days after the first session. It lasted 90 minutes, with a 15-minutes break. This procedure is accepted in populations with ID (Heiman and Margalit, 1998; Lifshitz, Shnizer and Mashal, 2015).

The interviewer read the questions to the participants in order to eliminate any reading problems. After each question, the participants were asked whether they understood the question. If not, the interviewer repeated and explained the question. The findings indicate that this procedure did not harm the reliability of the questionnaire. The alpha coefficient of all the questionnaires ranged between α = .60 -.85.

Design

We compared the social-emotional skills of the couples and the singles groups. Then we examined differences between singles and couples on the singlehood battery questionnaires. All questionnaires were analyzed using General Linear Model ANOVAs. We used a two-way repeated ANOVA (2 x 2) with status (singles/couples) and gender (men/women) as the independent variables (between-subject factor) and the subscales of each questionnaire as the dependent variables (within factors). Our goals were to examine the dominance of the subscale in each questionnaire, i.e. which of the three attachment styles would receive the highest score. In addition, we examined whether interaction would be found between the subscales and the independent variable. Therefore, we preferred the repeated analyses over a single ANOVA test.

Findings

The findings indicate that all dependent variables were normally distributed in the study groups (p > .05). Parametric analyses were therefore performed for each group separately.

Difficulties with Basic Social/Emotional Skills

Self-concept – “I am/He is” questionnaire : (Glanz, 1989) [33] A two-way repeated ANOVA (3 x 2 x 2) was performed to examine differences in self-concept, with status/gender as the betweensubject factor and three self-concept subscales as the withinsubject variables. A significant main effect was found for gender, F(1, 90) = 4.33, p < .05, η2 = .05 (for men: M = 2.49, SD = .44 and for women: M = 2.27, SD = .66). The status x gender interaction was also significant, F(1 ,90) = 4.22, p < .05, η2 = .050.

All participants expressed medium to high self-concept in both measures (2 out of 3). Bonferroni analysis indicated that among couples, men have a higher self-concept in both personal and physical appearance traits than women, t(53) = 3.02, p < .01, whereas single men and women exhibit the same scores.

Friendship quality questionnaire: (Margalit, 1996) [24] A twoway repeated ANOVA (3 x 2 x 2) with status/gender as the between-subject factor and friendship quality as the withinsubject variable indicated main effects for the four subscales, F(2, 89) = 8.93, p < .001, η2 = .170. Support and esteem (M = 2.62, SD = .49), and shared leisure (M = 2.58, SD = .47) were significantly higher than conflict and making-up (M = 2.29, SD = .62). No main effect was found for status, F(1, 90) = .98, p > .05, η2= .010, and for gender, F(1, 90) = 0.01, p > .05, r η2 = .002.

Interpersonal orientation behavior questionnaire: (Schutz, 1978; 1994) [36,37] A two-way repeated ANOVA (2 x 2 x 2) performed with status/gender as the between-subject factor and behavior style as the within-subject variable indicated a main effect for behavior styles, F(3, 86) = 61.03, p < .001, η2 = .680, with no main effect for status, F(1, 88) = .67, p > .05, η2 = .008, or for gender, F(1, 88) = .06, p > .05, η2 = .001. None of the interactions were significant.

Post hoc analysis indicated that the expressed affect (M = 2.56, SD = .49) and desired affect (M = 2.68, SD = .45) were significantly higher than expressed control (M = 2.08, SD = .59) and desired control (M = 1.70, SD = .54).

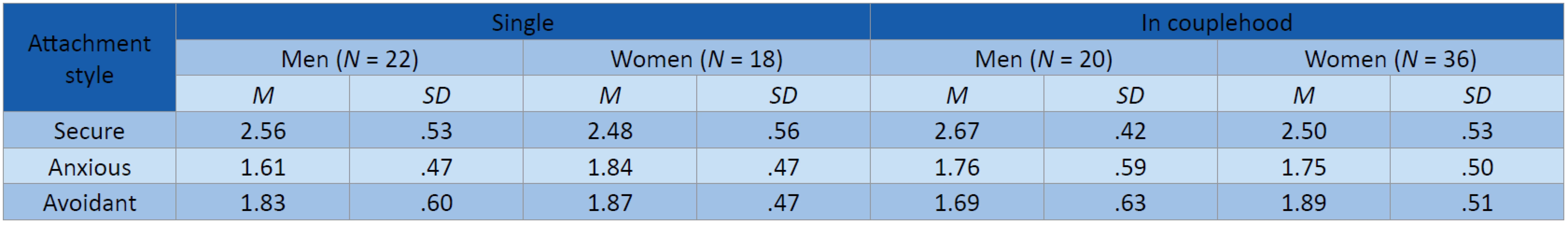

Singlehood According to the Psychological Theories

The attachment questionnaire: A two-way repeated ANOVA (3 x 2 x 2) performed with status/gender as the between-subject factor and attachment style as the within-subject variable indicated a significant main effect for attachment style, F(2, 92) = 48.76, p < .001, η2 = .520. No significant main effect was found for status (single/couple), F(1, 93) = .003, p > .05, η2 = .001, for gender, F(1, 93) = .17, p > .05, η2 = .002, and for attachment style, F(2, 92) = 48.76, p < .001, η2 = .520. The interactions status x gender, F(1, 93) = .22, p > .05, η2 = .002, attachment x status, F(2, 92) = .44, p > .05, η2= .009, and gender x status x attachment, F(2, 92) = 1.91, p > .05, η2 =.04 were not significant. Table 1 presents the means and SDs of the attachment style according to status and gender (Table 1).

1. Attachment Style: Means and SD according to Status and Gender (N = 96).

The findings indicate that the secure attachment style was significantly more common (M = 2.53, SD = .51) in the entire sample than the anxious (M = 1.74, SD = .51) and avoidant (M = 1.53, SD = .55) styles.

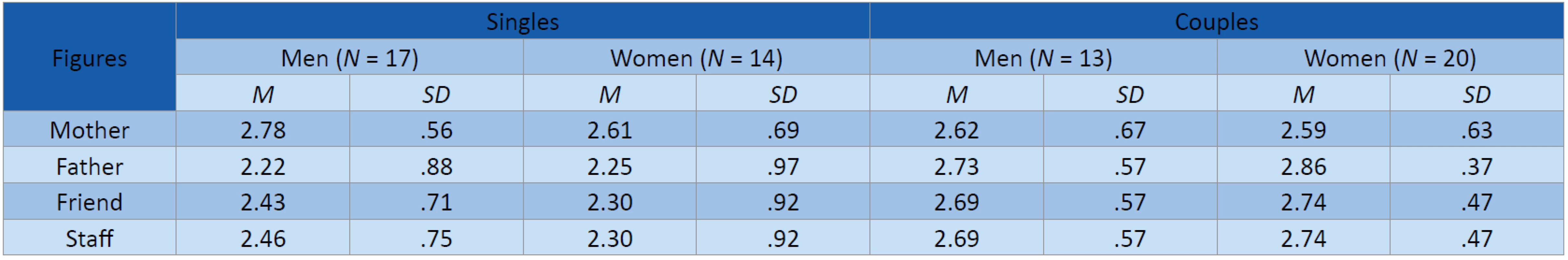

Social networks questionnaire: (Furman and Buhrmester, 1985) [41] A two-way repeated ANOVA (4 x 2 x 2) was performed with status/gender as the between-subject factor and the quality of social network as the within-subject variable. No main effect was found for status, F(1 ,56) = .36, p > .05, η2 = .006 or for gender, F(1, 56) = .04, p > .05, η2 = .001. The status x gender interaction was also not significant, F(1,56 ) = 1.67, p > .05, η2 =.030. A significant interaction was found for status x relationships with the different figures, F(3, 54) = 3.20, p < .05, η2 = .150. Table 2 presents the means and SDs of the social networks according to status and gender (Table 2).

2. Social Networks Questionnaire: Means and SD according to Status and Gender (N = 64).

Table 2 indicates that the participants ranked their relationships with four key figures as relatively high (above 2.00 out of 3.00). Bonferroni analysis for examining the source of the interaction indicated that relationships with fathers were significantly higher among people in couples than among singles, t(70) = 3.20, p < .010. The singles ranked their relationships with mothers higher than their relationships with fathers, friends and staff, F(3, 28) = 3.85, p < .05, η2 = .290, whereas no difference was found in the ranking of the relationships with the different figures among couples, F(3, 30) = 1.24, p > .05, η2 = .110.

Intimacy questionnaire (FIS): (Descutner and Thelen, 1991) [43] A two-way repeated ANOVA (2 x 2 x 2) performed with status/ gender as the between-subject factor and intimacy as the withinsubject variable did not reveal main effect for status, F(1, 89) = 2.76, p > .05, η2 = .030 or for gender, F(1, 89) = .87, p > .05, η2= .006. A main effect was found for the intimacy measures, F(1,90) = 4.32, p < .05, η2 = .050. Active intimacy (M = 2.33, SD = .57) scored higher than verbal intimacy (M = 2.23, SD = .61). A significant interaction was found for intimacy x gender, F(1, 90) = 4.00, p < .05, η2 = .04 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 indicates that the scores for both intimacies were relatively high (2 out of 3). Post hoc analyses indicated that among the men (beyond status), active intimacy was significantly higher than verbal intimacy, t(39) = 2.79, p < .01. No such difference was found among the women, t(53) = 0.10, p > .05.

Adolescents intimacy questionnaire: (Shulman et al., 1997) [44] A two-way repeated ANOVA (2 x 2 x 2) performed with status/ gender as the between-subject factor and the intimacy as the within-subject variable did not reveal a main effect for status, F(1, 89) = 2.76, p > .05, η2 = .030, for gender, .F(1, 89) = .87, p > .05, η2 = .006, and for the intimacy measures, F(1, 89) = .20, p > .05, η2 = .002. Furthermore, none of the interactions were significant: status x gender, F(1, 89) = .57, p > .05, η2 = .010, intimacy x status, F(1, 89) = .30, p > .05, η2 = .003, intimacy x gender, F(1, 89) = .01, p > .05, η2 = .001. The mean of the personal intimacy (M = 2.02, SD = .63) and the intimacy with others (M = 2.18, SD = .72) was relatively high for the entire sample (out of 3).

Singlehood according to the Sociological Perspective

All (100%) of the couples and 97% of the singles expressed their desire to have a steady partner; 97% of the couples and 80% of the singles expressed their desire to marry with no significant difference between the groups, χ2 (1)= .004, p > .05.

The Expectations for Marriage Scale (RMS): (Vilchinsky, 2004) [45] A two-way repeated ANOVA (3 x 2 x 2) was performed with status/gender as the between-subject factor and expectations for marriage as the within-subject variable. A main effect was found for expectations for marriage, F(1, 90) = 8.95, p < .01, η2 = .090 (M = 2.54, SD = .63; M = 2.36, SD = .69 for emotional and practical expectations, respectively). No main effect was found for status, F(1, 90) = 3.50, p > .05, η2= .040, or for gender, F(1, 90) = 5.75, p < .05, η2 = .060. The status x gender interaction, F(1, 90) = 5.67, p < .05, η2 = .06 was significant. The expectations for marriage x status, F(1, 90) = .10, p > .05, η2 = .06, and other interactions were not significant.

Bonferroni analysis showed that those in couple relationships expressed emotional expectations significantly more than practical expectations , t(54) = 3.76, p < .001, whereas singles expressed emotional and practical expectations to the same extent. Furthermore, the singles expressed practical expectations significantly more than couples, t(92) = 2.96, p < .010.

Preferred traits in the partner questionnaire: (Shachar and Sharon, 2010) [26] A two-way repeated ANOVA (2 x 2 x 2) performed with status/gender as the between-subject factor and social/practical traits as the within-subject variables. No main effect was found for status, F(1, 90) = .76, p > .05, η2 = .010, for gender, F(1, 90) = .63, p > .05, η2 = .010, or for desired traits, F(1, 90) = 1.11, p > .05, η2 = .010. A significant status x gender interaction was found, F(1,90) = 4.81, p < .05, η2 = .05.

Bonferroni analysis showed that single women expressed significantly higher desired traits in partners (social traits, M = 2.85; SD = .30, practical traits, M = 2.76; SD = .31) than women in couple relationships (social traits, M = 2.51; SD = .71, practical traits, M = 2.59; SD = .67), t(51) = 1.85, p < .050). Thus, single women have higher expectations for the existence of both types of traits in their partners than women in couple relationships do.

Discussion

Two main issues are at the core of the discussion: Attribution of the singlehood phenomenon among adults with ID as well as similarities/differences in singlehood among adults with ID and the general population.

We used a triadic model to examine singlehood in a population with ID. The first dimension examines whether singlehood in a population with ID stems from their social/emotional skills impairment which is inherited in the ID itself. The most intriguing finding is that singlehood among adults with ID is not a byproduct of their ID. Our hypothesis of higher emotional/social skills among couples with ID compared to singles was refuted. Contrary to previous prejudices (Wolfe, 1997) [13], singlehood among adults with ID cannot be attributed to a deficit in social/emotional skills of the singles compared to the couples (at least for individuals with a mild and moderate level of ID). Singles and couples with ID exhibited the same level of self-concept, quality of friendship and social interaction.

Figure 1 Active and verbal intimacy x gender interaction.

The second dimension n the triadic model relates to psychological theories of singlehood. Our hypothesis of a higher attachment style and intimacy among couples compared to the singles was also refuted. Both groups exhibited a secure attachment style, with no group differences. Our results contradict findings in the general population indicating that couples with typical development exhibit a more secure style, whereas singles exhibit avoidant or anxious styles (Schachner et al., 2008) [19]. Secure attachment style was found in this population in other studies (De Schipper, Stolk and Schuengel, 2006). Our participants live in community residences where the caregivers are taught to empower and strengthen the self-confidence and self-image of the residents. The secure style found in this study apparently reflects relationships of trust and closeness that develops between the caregivers and residents.

However, significant differences were found in the attachment hierarchy toward close figures between singles and couples with ID. Couples reported greater support from fathers and from friends. Singles positioned mothers in first place, and fathers and close friends in second place. In this respect, the social networks of singles and couples with ID resemble those of adults with typical development (Trinke and Bartholomew, 1997) [48].

The higher attachment of singles with ID to their mothers, which was found in this study, reflects overprotection, a common phenomenon in populations with ID (Glidden, Billings, and Jobe, 2006) [20]. Mothers are more involved in caring for their child with ID than fathers (Glidden et al., 2006). Barak-Levy and Atzeba-Poria (2013) [49] found that mothers were prone to an emotional coping style in reaction to their children’s diagnosis of developmental delay, whereas fathers tended to use a more cognitive coping style.

Our findings refute the myth that adults with ID are interested only in sexual relations (Lesseliers and VanHove, 2002) [50], and exhibit lower intimacy skills. The singles and couples exhibit high levels in all four intimacy categories: personal intimacy, intimacy with others, verbal and active intimacy. Our findings suggest that persons with ID can provide support and affection for friends of the same sex as well as to those of the opposite sex. Their social and emotional skills enable them to maintain rewarding, verbal and active, intimate relationships.

The third dimension in the triadic model reflects the sociological perspective. Our findings support the selective mechanism (Liefbroer, 2007), which postulates that persons with realistic values are selected into marriage, whereas those with high expectations remain single. They also correlate with the adaptation mechanism, which postulates that attitudes towards couplehood and marriage are a result, rather than a cause, of differences in a person’s status. Of our participants with ID, 99% of both singles and couples expressed a desire to have a heterosexual relationship and 74% expressed a desire to marry. This means that the singlehood prevalent in the ID culture is not a choice. Are we as a society ignoring their needs? Do we help them the chance to fulfill their wishes?

The study did indicate different expectations patterns from marriage and partners in the singles and couples with ID. The emotional expectations of the couples with ID were higher than their practical expectations, giving greater weight to emotional expectations. They understood the meaning of emotional needs in family life better than the singles who weighted emotional and practical expectations equally. Furthermore, the singles considered the practical expectations more than the couples. Put differently, the couples’ marital expectations were more moderate than those of the singles.

A similar trend was found in expectations from partners. The scores of personal and practical traits among women in couple relationships were low, suggesting that these women are more realistic in their expectations from their partners. Single women gave high scores to both types of traits, indicating that they may have unrealistic expectations from their partners. No differences were found between the two types of traits among the men in both groups.

Single women with ID cannot find partners because their demands are too high, and they are unwilling to compromise. Their scenario of married life is utopian. They have an unrealistic partnership and marriage schema about finding a “knight in shining armor.” Those in couple relationships have a more realistic and balanced schema of partnership and marriage. They understand that they cannot “have it all.”

It is noteworthy that the singles and couples with ID in our study have similar cultural background. They live in a similar residential environment, they work in vocational centers or open market (with no significant differences between singles and couples) and are exposed to similar leisure activities and cultural values. Nonetheless, couples with ID present a more mature approach and more realistic expectations from marriage and partners. The question remains, how did the couples with ID acquire their couplehood and marriage schema. From the psychological perspective, our findings indicate different attachment pattern to their mothers and fathers, who serve as their main social agents. In the typical developed population, fathers’ parenting behaviors were associated with the quality of young adult’s relationships with a romantic partner. “Fathers’ parenting appeared more strongly related to these beliefs then did mothers’ parenting” (Dalton et al., 2006, p. 14). In this study we did not examine parental attitudes to intimacy and social life of their offspring with ID. We did found that singles with ID were more attached to their mothers while couples with ID were more attached to their fathers. Might the differences in expectations between the two groups be the result of their relationships with key personalities? Are they related to the exposure of singles and couples to other social agents such as mass media? These questions were beyond the scope of this study and should be examined.

Our study reflects the debate about the reliability of self-report questionnaires in measuring psychological issues self-concept and quality of life in a population with ID (Finlay and Lyons, 2001; Tsoi et al., 2013) [31]. In the method section, we specified the steps we took to overcome these barriers. It should be noted that our participants were classified as having mild/moderate ID. Several questionnaires revealed differences in answers according to status (singles and couples) or gender. The fact that participants’ responses differed from each other is a further indication that they understood the questions. As Finaly et al., wrote, “Many people with ID can participate in interviews and answer self-report questionnaires without these problems (p. 34).” This study heard the voices of adults with ID themselves, rather than through a proxy. In line with Tsoi et al. (2013), we believe that persons with ID can advocate themselves better than others can represent them.

While dating and matchmaking are accepted among singles with typical development, society remains silent regarding partnership, marriage and especially parenthood of adults with ID (Lesseliers and Van Hove, 2002) [50]. The life expectancy of adults with ID has increased; as in the general population, persons with ID will be faced with the morbidity and disease of older age. Being in a partnership or marriage might help them to better cope with the situation (Brown, 1996) [4]. Partnership could provide them with a close friend and companion with whom they share a wide range of experiences and social learning (Brown, 1996). In marriage, they can share physical chores, participate in social and physical events and increase their acceptance, participation and inclusion in society. It is our challenge to help them plan their future and prepare them for family life to the greatest extent possible.

Persons with ID meet in residential and vocational centers. Service providers should create social events that allow residents or participants to become better acquainted with each other. Moreover, a matchmaking organization adapted for people with ID should be created. Based on experience in the general population, it is recommended that special matchmakers be trained to work with adults with ID.

Limitations, Practical Implications and Future Research

Sample size: The study employed multiple statistical tests on the same sample. In some of the analyses, the alpha coefficient reached, and in some surpassed, p < .05. The small sample size is a result of the need to obtain the parents of singles’ consent for their children’s participation in the study. A larger sample would help obtain higher levels of significance for the various questionnaires, and enhance the validity of the interviewing techniques. Nevertheless, this size is acceptable in special populations such as ID and ASD (Bauminger-Zviely & Agam-Ben - Artzi, 2014; Tzuriel & Hanuka-Levy, 2015) [27,28].

Further research using qualitative interviews with singles and couples with ID could elucidate the debate about singlehood out of choice-chance in this population and validate the results of the quantitative questionnaires. In this study, we focus on specific psychological and sociological theories that explain singlehood in the general population. Using additional theories would help achieve a better understanding of singlehood in a population with ID. Examining other personal traits, such as the “big five" of singles and couples, is also recommended.

Etiology: We did not differentiate between adults with and without Down syndrome due to the small sample size in each group. Examining differences in the study measures with reference to etiology is recommended.

Controls with typical development: We found similarities in singlehood among adults with ID and those with typical development. Comparing singlehood in the two populations with the same questionnaires would validate our results.

Parent’s perspective: Our findings revealed differences singles’ and couples’ social networking with their parents. The parents’ perspective was not examined but should be in future research. Differences in the exposure of singles and couples with ID to other social agents should be examined.

Residence type: Our participants live in community residences. We recommend that future studies examine the results are different for adults with ID living with their parents .

Attitudinal change: There is a need for action aimed at altering the attitudes of policy makers and staff towards partnership and marriage of adults with ID.

Family Life Education: In the population with typical development, family life education programs begin in adolescence and continue throughout the lifespan. A spiral program of Family Life Education, including couplehood and marriage, should be designed for adolescents and adults with mild/moderate ID.

Cultural differences: The selective/adaptation mechanism (Lesthaeghe and Moors, 2002) postulates that societal and cultural values shape attitudes towards family structure. We recommend conducting an international study of singlehood, partnership and marriage in populations with ID in the western world as well as in a traditional societies (including Arab, ultraorthodox Jewish and Christian), in order to better understand their emotional and social needs and to promote their quality of life around the world.

Corresponding Author:

Hefziba Vahav,

Associate Professor,

Head of ID Majoring Program,

Special Education Department,

School of Education,

Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel,

Tel: 972-52-2282276,

E-mail: efziba@013net.net

Sources

1. Goodwin PY, Mosher, WD, Chandra A (2010) Marriage and cohabitation in the United States: A statistical portrait based on cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23 28 : 1-45.

2. Poortman AR, Liefbroer AC (2010) Single’s relation attitudes in a time of individualization. Social Science Research 39 : 938-949

3. Lahad K (2012) Singlehood, waiting, and the sociology of time. Sociological Forum 27 : 163-186.

4. Brown RI (1996) Partnership and marriage in Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice 4 : 96-99.

5. Mureno JD (2013) Couple therapy and support: A positive model for people with intellectual disabilities. NADD Bulletin V X, 5 article 1.

6. May D, Simpson, MK (2003) The parent trap: Marriage, parenthood and adulthood for people with intellectual disabilities. Critical Social Policy 23 : 286-296.

7. Arias B, Ovejero, A, Morentin R (2009) Love and emotional well-being in people with intellectual disabilities. Spanish Journal of Psychology 12 : 204-216.

8. Reiter S, Neuman, R (2013) The characteristics the meanings and the implications of a romantic relationship from the point of view of people with intellectual disability who live in a relationship: Comparison between quality of life and self-concept of people who are in a romantic relationship and in a friendship relationship. Beit Dagan: KerenShalem Press (Hebrew)

9. Tsutsumi AA (2009) Sexual health and behavior of mentally retarded pupils in Japan. US-China. Education Review 6 : 61-66.

10. Young R, Gore N, McCarthy M (2012) Staff attitudes towards sexuality in relation to gender of people with intellectual disability: A qualitative study.J Intellect DevDisabil 37 : 343-347.

11. Bogdan RC, Taylor SJ (1994) The social meaning of mental retardation (Rev. ed) New York: Teachers College Press.

12. O’Brien J, O’Brien CL (1993) Unlikely alliance: Friendship and people with developmental disabilities. In A. Amado (Ed.) Perspective in Community, Lithonia, GA: Responsive Systems Associates (pp. 1-31)

13. Wolfe PS (1997) The influence of personal values on issues of sexuality and disability. Sexuality and Disability, 15 : 69-60

14. Bowlby, J (1973) Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

15. Bowlby, J (1988) A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge.

16. Hazan C, Shaver PR (1994) Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychological Inquiry 5 : 1-22.

17. Liefbroer AC (1998) Free as a bird? Well-being and family-life attitudes of single young adults. In LA Vaskovics, HA Schattovits (Eds.): Living arrangements and family structures: Facts and norms. 2nd European Conference on Family Research, 12-14 June 1997, Vienna (pp. 99-110) Vienna: Austrian Institute for Family Studies.

18. Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2011) An attachment perspective on interpersonal and intergroup conflict. In J Forgas, AKruglanski, K Williams (Eds.): The psychology of social conflict and aggression (pp. 19-36) New York: Psychology Press.

19. Schachner DA, Shaver, PR, Gillath O (2008) Attachment style and long-term singlehood. Personal Relationships 15 : 479-491.

20. Glidden LM, Billings FJ, Jobe M (2006) Personality, coping style and wellbeing of parents rearing children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 50 : 949-962.

21. Erikson EH (1963) Identity and Development. New York: Norton.

22. Seligman S, Shanok, R (1996) Erikson our contemporary: His anticipation of an intersubjective perspective. Psychoanalytic and Contemporary Thought 19 : 339-366.

23. Shulman S (1993) Close friendship in early and middle adolescence: Typology and friendship reasoning. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 60 : 55-71.

24. Margalit, M (1996) Trends of development in special education: Promoting the coping with loneliness, friendship and sense of coherence. In D. Chen (Ed.): Education towards the twenty-first century (pp. 489-510) Tel-Aviv: Tel-Aviv University, Ramot (Hebrew).

25. Hook MK, Gerstein LH, Gridley, B (2003) How close are we? Measuring intimacy and examining gender differences. Journal of Counseling and Development 81 : 462-472.

26. Shachar R, Sharon J (2010) To be singles in Israel: Attitudes of single men and women towards singlehood, marriage and family. Yearbook of Education and Around It. In N Aloni (Ed.). Education and its context (vol. 32, pp. 276-290) Tel-Aviv: Kibbutzim College of Education (Hebrew)

27. Bauminger-Zviely N, Agam-Ben-Artzi G (2014) Friendships in young children with HFASD: friend and non-friend comparison. J Autism DevDisord 44 : 1733-1748.

28. Tzuriel D, Hanuka-Levy D (2015) Siblings’ mediated learning strategies in families with and without children with intellectual disabilities. Am J Intellect DevDisabil119 : 565-588.

29. Dunn L, Dunn L (1997) Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (3rd edition revised) Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

30. Bellugi U, Wang, PP (1998) Williams syndrome: From cognition to brain to gene. In G Edelman and BH Smith (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

31. Finlay WML, Lyons E (2001) Methodological issues in interviewing and using self-report questionnaires with people with mental retardation. Psychological Assessment 13 : 319-335.

32. Miller M, Burstow P (2010) Guidance for people who commission or produce Easy Read information. MencapCymru, Wales: Learning Disability.

33. Glanz, I (1989) I am like this and he is like this, comparative self-concept test. Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University (Hebrew)

34. Lifshitz H, Hen I, Weiss, I (2007) Self-concept, adjustment to blindness and quality of friendship among adolescents with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness 101 : 96-107.

35. Parker JG, Asher SR (1993) Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood, links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology 29 : 611-621.

36. Schutz WC (1978) FIRO-Awareness scale manual. Palo Alto, CA: Grove.

37. Schutz W (1994) The human element: Productivity, self-esteem and the bottom line. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

38. Efrati S (2001) Similarity between spouses in the level of interpersonal needs. MA Thesis. Ramat-Gan: School of Education, Bar-Ilan University (Hebrew)

39. Tolmenz R (1988) Fear of death and attachment styles. MA Thesis. Ramat-Gan: Department of Psychology, Bar-Ilan University (Hebrew)

40. Larson FV, Alim N, Tsakanikos, E (2011) Attachment style and mental health in adults with intellectual disability: Self-reports and reports by careers. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities 5 : 15-23.

41. Furman W, Buhrmester D (1985) Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 21 : 1016-1024.

42. Heller T, Miller AB, Hsieh K, Stern H (2000) Later life planning: Promoting knowledge of options and choice making. Mental Retardation 38 : 395-406.

43. Descutner CJ, Thelen MH (1991) Development and validation of a Fear-of-Intimacy Scale. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 3 : 218-225.

44. Shulman S, Laursen B, Kalman Z, Karpovsky, S (1997) Adolescent intimacy revisited. J Youth Adolesc 26 : 597-617.

45. Vilchinsky N (2004) Expectations for marriage among Israeli singles. Paper presented at the seventh scientific conference of the Peleg-BiligCenter for the Study of Family Well-Being. Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University.

46. Division of Persons with ID, Ministry of Welfare (2014) Statistical trends of the population with ID. Jerusalem: Government Press.

47. Wolfensberger, W (2002) Social role valorization and, or versus, empowerment. Mental Retardation, 42 : 252-258.

48. Trinke SJ, Bartholomew, K (1997) Hierarchies of attachment relationships in young adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 14 : 603-625.

49. Barak-Levy Y, Atzaba-Poria N (2013) Paternal versus maternal coping styles with child diagnosis of developmental delay. Research Developmental Disability 34 : 204.

50. Lesseliers J, Van Hove G (2002) Barriers to the development of intimate relationships and the expression of sexuality among people with developmental disabilities: Their perceptions. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 27 : 69-81.

Labels

Clinical psychology

Article was published inActa Psychopathologica

2015 Issue 2:12

Most read in this issue- Clinical Trials in Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology: Science or Product Testing?

- Singlehood among Adults with Intellectual Disability: Psychological and Sociological Perspectives

Login#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Forgotten passwordEnter the email address that you registered with. We will send you instructions on how to set a new password.

- Career